The NCAA Tournament is great. A March Madness buzzer-beater is the greatest. As this year’s tourney gets set to tip off, we talked to eight former players about what it’s like to take the big shot at the end of the game (or, in the case of the 2010 Butler Bulldogs, to watch one of your teammates take it). Sometimes you miss, sometimes it goes in, and sometimes, even if the ball goes through the net, you don’t end up as the hero.

Ty Rogers, Western Kentucky University

In 2008, the senior guard hit a 26-foot three-pointer as the clock expired in overtime to give No. 12 seed Western Kentucky a 101–99 win over No. 5 seed Drake in the first round of the West Regional.

I was just a role player. The play was not drawn up for me by any means. We had an NBA player on the left wing, Courtney Lee, and Tyrone Brazelton, who had 33 points. Basically the play was for Tyrone to get as far to the rim as he could and of course knowing he’s got Courtney on the left wing if he needed it. But I’m a man of faith. I’ve always believed everything happens for a reason, and it was kind of unlike me, but walking out on the floor out of the timeout, I told Tyrone, “Listen, if you get in trouble, don’t be afraid to kick it to me.” And I’m assuming God kind of led me to tell Tyrone that. He ran down the floor, tried to get to the rim, and was cut off by three defenders. I was trailing behind him, he kicked it to me, and I was able to knock down the shot.

When you look at the picture of it, it looked like I was pretty well-defended, but I pretty much never had a doubt that it was going in. It looked good from the time it left my hand and it was a pretty smooth release.

To know that you’d won a game and you’re actually advancing in the tournament? I lost complete control of myself, running around the gym like crazy. I did. But it was kind of a pinnacle of years and years of hard work to get on that stage. I’m from a supersmall town, graduated [high school] with 60 kids. Even to play college basketball was a dream come true. It didn’t happen for a lot of kids where I’m from. As a little kid, I watched the Bryce Drew shot. I remember just thinking, Man, that’s amazing. To have a moment like that is crazy. It becomes like [being in] a little fraternity.

Nothing at that level had ever happened to me. I try to think that I’m a somewhat humble human being. But it’s changed my life. It really has. We moved on and beat San Diego and then gave UCLA a pretty tough game in the Sweet 16. So as far as just being back on campus, you were heroes for the last couple months [of the school year]. A large group of us were seniors. What a way to go out.

I still live in Bowling Green, where Western Kentucky is. I have a 6-year-old little girl, and she’s in elementary school. Her teachers, they kind get a kick out of knowing that she’s my daughter. Her kindergarten teacher showed the class the clip of my shot around this time last year.

It almost seems surreal now. You play a sport, you work at it your whole life, just to get on that stage. Then basically you’re remembered—in my case—for five seconds of your career. When I watch the highlight, I feel just like anybody else. You get excited. It’s neat to remember that it actually did happen.

Will Veasley, Butler University

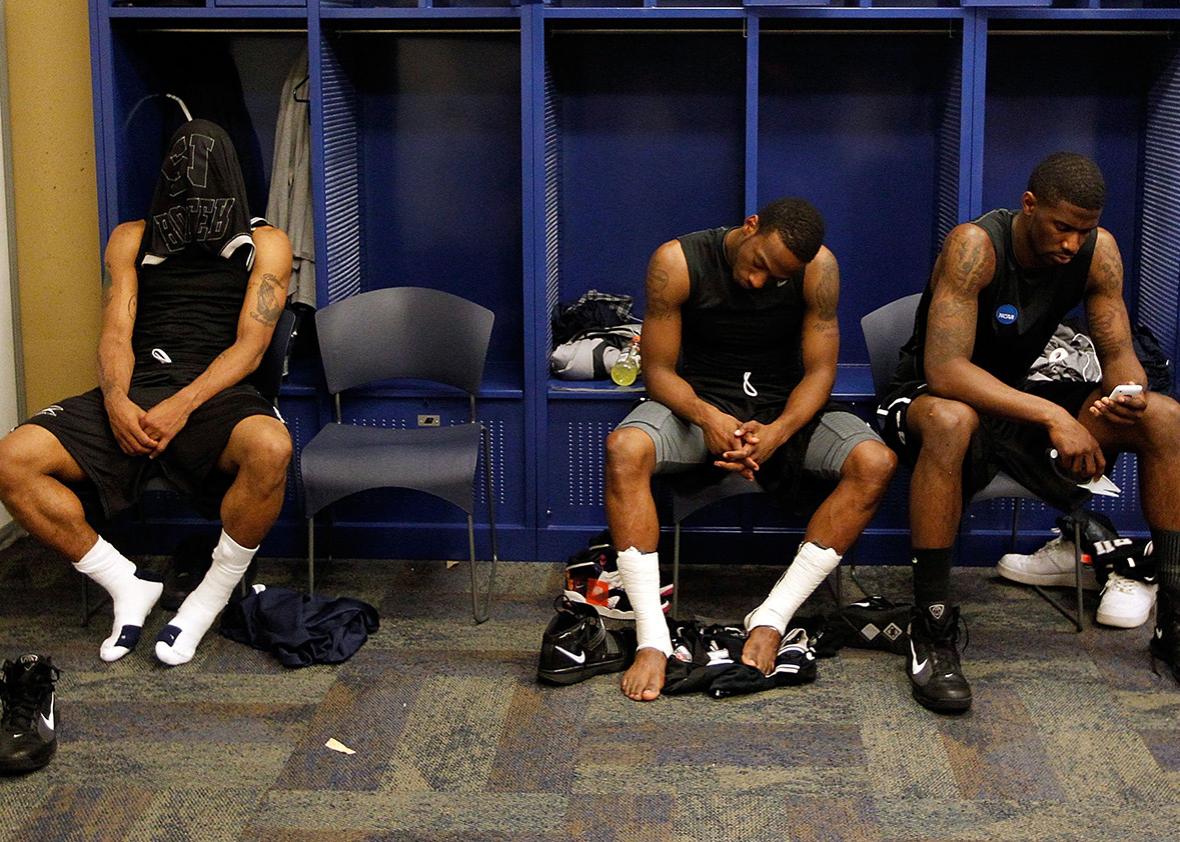

Kevin C. Cox/Getty Images

With his team down two in the 2010 national title game, Butler’s Gordon Hayward launched a half-court shot that would’ve given the Bulldogs the win over Duke. Alas, it missed, clinching the championship for the Blue Devils. Veasley, a senior guard, was on the floor for Hayward’s heave.

It’s still surreal. One of my friends actually just sent me the “One Shining Moment” from our tourney run, and it ends with the shot, and there’s a shot of me just staring up there looking like, It’s over. Oh man.

Now I can probably look back and laugh and joke. Everybody’s like, “It was that close!” You know what? When you were there live, it was even closer. It’s unbelievable that that shot did not go in. Movie-style, slow motion, it just took forever for the ball to get up there. And then it hit the backboard, it hit the rim, and you’re thinking it’s going in. After the run that we had, the way that we played all tourney, I think everybody was thinking that it had to go in. And when it didn’t go in, I don’t think I’ve ever been shocked like that before.

I don’t think it really hit me until we got back into the locker room and coach [Brad] Stevens was talking to us and the media came in. I think that’s when I realized, Man, it didn’t go in. We lost. This run is over now. That’s when you knew it was final. It was done.

It’s always fun when people talk about it, even though I still haven’t been able to watch that championship game over again.

Jermaine Wallace, Northwestern State University

Doug Daniels

In the final seconds of Northwestern State’s 2006 first-round game against Iowa, Wallace, a senior guard, tracked down a long rebound and launched a desperation three-pointer. The ball fell through the net, giving the the 14th-seeded Demons a 64–63 win over the No. 3 seed Hawkeyes.

The play was designed for Kerwin [Forges]. My job was just to crash the boards if he missed. When he missed and I got the rebound, I just peeked at the shot clock on the other basket. I saw I had about four seconds, so I knew I had time to make one move. I figured I could do a stepback and just launched the three.

I’d hate to say I knew it was going in because that would be a lie, but I had a feeling it was a good shot. It felt good. It felt real good. Somebody gave me my first still picture of it, where you can see [Adam Haluska] contesting the shot. The angle I was at, at my highest point, was like, damn.

When I saw it go in, I was on the floor. I immediately popped up like a jack-in-the-box. I really thought the game was over so I immediately started celebrating.

To be honest with you, I never go on YouTube and just type in my name. Every time I see it, it’s around this time, March Madness time, whenever somebody brings it up. It’s still something that especially my family remembers. They’ll never let me forget that. When I go back to my alma mater that’s about all we talk about.

What my teammates did in order for us to even get to that situation—we were down [17 in the second half]. For us to even come back and be two points down …

My teammates, after all these years, we still care for each other. I appreciate them. They say, “Great shot.” But I tell them, “Y’all don’t understand. Y’all are this shot.”

Drew Nicholas, University of Maryland

With his team trailing by a point in the first round of the 2003 South Regional, Nicholas took an inbounds pass, dashed almost the length of the court, and hit a three-pointer at the buzzer to give No. 6 seed Maryland a 75–73 win over No. 11 seed University of North Carolina at Wilmington. The senior guard immediately ran off the court, skipping toward the locker room.

We had fouled a kid, [Aaron Coombs]. He was like a 50 percent foul shooter. We’re up one, and we’re pretty confident. Alright, he’s gonna miss at least one. He’s gonna give us one. Of course he knocks down both. We’re down one now. Coach [Gary] Williams calls a timeout. Originally the play was designed for [Steve] Blake to get it and then go try to make a play with five seconds [remaining]. And then I was kind of the secondary guy. Coming out of the timeout, I told Tahj Holden, who was taking the ball out of bounds, “Man, if Steve isn’t open, throw me that damn ball.” But probably not in those words.

And once I got it, then it just becomes a blur a little bit. I just remember having to get down the court as fast as possible, and I knew I had to get a shot off. I thought I had a good feel [of] how much time was left, and I knew I had some time to get it off. And then the rest is history, man.

I thought because I was going so fast and I jumped off of one leg, I thought I shot an air ball. I didn’t think I put enough on it. And then when I saw that thing go through the net, I was out of there. I was gone. I had to go.

It was such a cool moment. [Washington Post columnist Michael] Wilbon was big back then and sat and talked to me for a good 10 to 15 minutes. I just remember probably getting 50 or 60 voicemails on my cellphone. Everybody’s congratulating me.

Here’s the thing that I think a lot of people don’t really remember: My sophomore year we had the game where [we] were up 10 against Duke with 54 seconds [to go], and then we ended up losing in overtime. Blake had fouled out with like a minute left and I came in for Blake, and I was the one who missed four free throws. I had a turnover. I was kind of like the goat. It’s funny, I had a great senior year, but potentially I think people really wouldn’t have remembered it as such if I had never made that shot. I always look at it as kind of my chance for redemption a little bit. And I think that now with that shot, people moreso remember me for that shot against Wilmington as opposed to maybe the kid who missed the free throws against Duke.

You get introduced to somebody, and you say, “Hey, I’m Drew Nicholas,” and then everybody’s giving me their rendition of where they were when I hit the shot. Whether it was at a bar or in their parents’ basement or knocking over a living room table. It’s crazy.

Sean Woods, University of Kentucky

Christian Laettner’s last-second shot to give Duke a 104–103 overtime win over Kentucky in the 1992 East Regional final is the most famous buzzer-beater of all time. Just before that, with 2.1 seconds left in overtime, Kentucky’s Woods, a senior guard, hit a high-arcing runner over Laettner to give the Wildcats a 103–102 lead.

When you’re growing up like I did, you dream of situations like that. It was just a play we drew up that was either for me to penetrate or penetrate and kick. If you have an opportunity to make a shot, you’re going to take it. And I did it.

I had to go against Shaquille O’Neal in the SEC. So you had to throw it high off the glass. With that particular shot I just wanted to give it a chance to either hit the back of the rim and go in or give us a chance to tip it. I hit the backboard just right, and it went straight in.

You think you won the game with 2.1 seconds left. What’s unfortunate is that there was time left on the clock, so they got the last shot off. Fate prevailed. Christian was perfect that night.

When I was a senior at Kentucky, Pat Riley—because he played at Kentucky—came in and visited us and made a great quote. He said, “Man’s biggest fear is fear of extinction.” [We fear] going through life without having a significant impact on something. So from that standpoint, that’s considered the greatest college basketball game ever. Being a part of that is very gratifying.

Rodney Chatman, University of Southern California

James Forrest, Georgia Tech

In 1992, No. 7 seed Georgia Tech and No. 2 seed USC faced off in the second round of the Midwest Regional. After USC’s Chatman, a junior guard, hit a baseline jumper with 3.4 seconds left to give the Trojans a two-point lead, the Yellow Jackets got one more chance when the referees ruled that senior center Matt Geiger’s long inbounds pass ricocheted off Chatman’s leg and out of bounds. Now at midcourt with 0.8 seconds left, Geiger inbounded the ball to freshman forward Forrest, who sank a turnaround three—that season he’d missed his only three previous attempts from beyond the arc—to give Georgia Tech a 79–78 victory.

Chatman

We drew up a play for Harold Miner. He was the guy at the time. And he was covered. So coach [George] Raveling said if he was covered to go ahead and take my man. I couldn’t get [Miner] the ball so the next option was me. I just went hard right. I saw the daylight. I went to the basket, went to the baseline, and pulled up for a jump shot. We’re moving on. That’s your first thought process. Get ready to win it, without a doubt.

I actually was the one playing defense on [Jon] Barry when the ball went out of bounds. But it really went off his foot. It didn’t go off my foot. But they gave it to them.

James Forrest kind of slipped away, kind of caught it, turned, and shot. I watch [the highlight] now, and there’s no bad feelings about it. But in the early years there was. It was, I don’t want to watch this shit. But it got to a point where it is a piece of history. My wife and son got the thing programmed on their phones. So yeah, they watch. It’s always on YouTube.

It’s quite funny. I live in Atlanta now, so I see James Forrest all the time.

Forrest

I coach kids now. A lot of my kids, when they show the shot every March Madness they’re like, “Coach, we saw that shot, did you really make it? How did it happen?

The funny thing was that the shot was never even intended for me. But I saw the five-second count coming [on the inbounds pass], and I was like, “Matt throw me the ball! Throw me the ball!” And he threw it, and we’re talking about it 20-something years later. It’s amazing.

There was only 0.8 seconds left. We were supposed to set a double [screen] for Jon [Barry], and that didn’t work. And Travis [Best] was to pop one way. And I mean, no one got open. I just for whatever reason just trusted my instincts and ran. I was wide open. It was almost like I caught it and heaved it at the same time. Listen, you have to catch and shoot right away.

As I see it going in, it’s like, oh my god, and the first reaction was, I saw the bench. Coach [Bobby] Cremins had started walking toward coach Raveling to shake his hand. He looked like, Ohhhh. [Television commentator] Al McGuire yelled, “Holy mackerel!”

At that moment, you didn’t realize it would be one of the best buzzer-beaters in NCAA history. You just don’t. It was unbelievable. When you’re an athlete and especially you’re young, you just don’t have the time to understand what just happened. That stuff takes time.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of the 2016 NCAA Tournament.

In the first round of the 1989 Southeast Regional, underdog East Tennessee State was on the verge of becoming the first No. 16 seed to beat a No. 1. But after building a 17-point first-half lead, the Buccaneers ended up losing to Oklahoma 72–71. As time expired, West, a sophomore guard, missed a desperation shot from just inside the midcourt circle.

You have to understand where a lot of us came from. I’m from North Carolina. A lot of us grew up in ACC country. I was a hair from going to Wake Forest. Jim Valvano wanted me. All of us ended up at East Tennessee State, but all of us should’ve been ACC and SEC. In our mind, we were trying to win a national championship.

We knew Oklahoma was No. 1, but we were just young and bright-eyed, and we actually went up by like almost 20 points on them. They had a good team, but we outplayed them all game.

It really wasn’t a shot at the end. It was really a throw. We were in Oklahoma’s backcourt on the sideline. We lined up in an I, and I was gonna fake back toward our goal, and [Chad Keller] was gonna throw me a pass running toward Oklahoma’s goal full court, but when I popped out, I ended up with the ball right there. Now here I am with three or four seconds, and I’ve got to go. So when I got like two steps inside of half court I just threw it up the best that I could, and of course you know how the rest went.

Sports Illustrated did an article on us in 1991. They asked me about the Oklahoma game, and I said, “Well, I remember looking up at the score, and looking up at [East Tennessee point guard Keith “Mister”] Jennings, and saying, ‘Hey man, we’re up 17 on Oklahoma.’ ” I can still see that score in my head. And it was my birthday, too. It was March 16. If I had a clean look at that shot, [the] 16–1 [curse] would’ve been over in ‘89 on my birthday. My life would’ve been totally different.

Interviews have been condensed and edited.