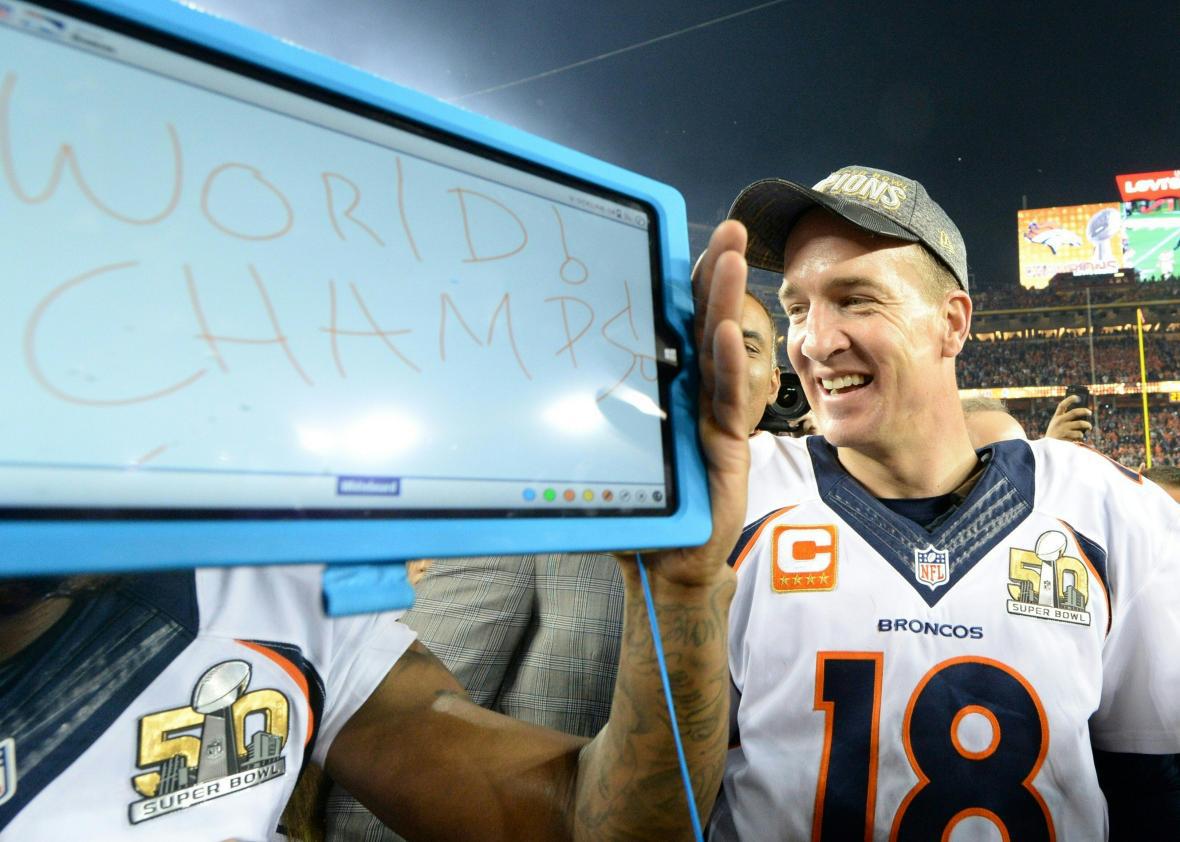

Zoom out far enough, and the arc of Peyton Manning’s career looks perfect and pre-ordained. The son of a football legend, Manning became a legend himself. He was a star quarterback in college, got selected with the No. 1 pick in the 1998 NFL draft, and became a star in the NFL. He set a bunch of passing records and won two Super Bowls, the second of those coming last month, when the 39-year-old returned from a mid-season injury to help the Broncos win a championship. On Sunday, ESPN reported that Manning is retiring after 18 years in pro football, making Super Bowl 50 a “dream ending” for one of the best players in league history.

Manning accomplished all of this while earning a reputation for being smart and funny—a brawny jock with the soul of a nerd. He threw for 539 touchdowns in his NFL career, but none of them are as easy to conjure as his loud, flapping audible calls at the line of scrimmage. He starred on Saturday Night Live, and he shilled for pizza and insurance. If someone invented insurance for pizza, he could probably sell that, too.

Son of football royalty becomes wealthy, successful athlete and pitchman. That’s Peyton Manning: an uncomplicated, all-American, riches-to-riches story.

Zoom in closer, and that career arc looks wobblier than a late-career Manning spiral. On the field, he was criticized constantly for putting up big numbers and losing the games that mattered—for not being clutch like his championship-winning brother Eli. He missed all of 2011 due to a series of neck injuries, and ended up getting cut by the Indianapolis Colts, the team he’d transformed from a loser to a perennial contender. Late last year, an Al Jazeera documentary strongly insinuated that Manning used human growth hormone, a performance-enhancing drug banned by the NFL. And more recently, news outlets have resurrected a decades-old allegation, a claim by an athletic trainer that Manning either mooned her or sexually assaulted her when he was a student at the University of Tennessee.

The critiques of Manning’s play and the frailty of his body were both inevitable, the sort of wobbles that afflict every pro athlete. Thanks to his outstanding skills, his longevity, and rule changes that favored the passing game, Peyton Manning ruled his sport like few players ever have. But every great player in every game (except maybe Stephen Curry) is subject to the same immutable laws: He will lose, he will get hurt, and he will get old.

Those have been the three sports axioms for millennia—I’m guessing the Lascaux cave paintings depict hunters choking in the clutch. Sports fandom is visceral and simple-minded. We learn to love sports as children, and as adults we hold our favorite athletes to child-like standards, both on and off the field. Back in February, my Slate colleague Jack Hamilton wrote that “sports are presented in terms of moral dichotomies, of Good and Bad and little to nothing in between. Players are either winners or losers. They work hard, or they’re lazy. They are selfless or selfish. They play the game the ‘right way’ or the ‘wrong way.’ They are innocents, or they are cheaters.”

Hamilton argued that Manning had been placed in the Good category. Whether or not you’d slot Manning there yourself, it’s undeniable that the conversation around him has never been particularly nuanced. A football player’s reputation is based largely on circumstances beyond his direct control. Manning’s record-setting stats were abetted by rule changes that favored the passing game. He also spent years of his prime carrying teams with subpar defenses, and had the good fortune to spend his worst season playing for a Denver Broncos squad with one of the best defensive units of all time. All of that’s not easy to express in binary terms, but that’s how we’ve always seen Peyton Manning: He’s a winner, except when he’s a loser.

Over the past few months, Manning’s story has gotten a whole lot messier. The HGH allegations were sketchy. Al Jazeera claimed the drugs were shipped to Manning’s wife, based on information received from a former intern at an anti-aging institute. If this was a witch hunt, though, Manning came out looking a little witchy. Every athlete who rants and raves on camera about how he never took performance-enhancing drugs inevitably took performance-enhancing drugs. Manning also brought in private investigators to go after that anti-aging-institute intern, and he paid Ari Fleischer to act as his crisis PR manager. When you hire George W. Bush’s press secretary, you’re ratcheting down the ceiling on your own likability.

But assuming that Manning did take human growth hormone, it would be hard to blame him. The guy had major neck problems, and he was doing whatever he could to extend his career. He wasn’t trying to enhance his performance. He was trying to perform, full stop—to give fans more of what they wanted to see. And besides, it’s not even clear that human growth hormone works. It’s not like he was taking East German anabolic steroids. We should all give the guy a break, and also he seems like a huge jerk.

It’s just as hard to reach a clear conclusion on the sexual assault claim. In 1996, a female trainer at the University of Tennessee accused Manning of pulling down his pants in the locker room. In the decades since, that moment has been cited in a sexual harassment claim, a defamation case, and a federal Title IX lawsuit. The athletic trainer, Jamie Naughright, hasn’t told a consistent story about what happened in the locker room. There’s strong evidence, too, that Manning isn’t telling the truth about the supposed mooning incident. This week, the MMQB’s Robert Klemko reported on the existence of a previously undisclosed witness, a football player named Greg Johnson who said Manning’s mooning was an innocent prank. The next day, ESPN published a story that argued there was no evidence that Johnson was even in the locker room.

There will never be a definitive, unchallenged account of what happened in the Tennessee locker room. What is clear is that Manning tried to sully his accuser’s reputation. In a book co-written with his father, he said that Naughright had “a vulgar mouth.” And as Nora Caplan-Bricker explained in her rundown of the allegations, in “a sworn deposition, the ghostwriter of the Mannings’ joint memoir also said that Peyton had spread innuendo about Naughright—specifically, a claim that the white trainer had a habit of sleeping with black athletes—to his father Archie Manning.”

After four years as a star quarterback in college and 18 years in the NFL, here’s what we know for sure about Peyton Manning: He threw a lot of touchdown passes, and he won a couple of Super Bowls. He’s done a lot of charity work. He’s starred in a bunch of commercials, but I’m guessing he doesn’t stand in his kitchen singing, “Chicken parm it tastes so good.” When someone accuses of him wrongdoing, he fights back, and he doesn’t always fight fair.

The only way you can be wrong about Manning is to claim with absolute certainty that you know who he is and everything he’s done. (Come on down, Shaun King of the New York Daily News!) The story of Peyton Manning’s career was always an easy one to tell. It still can be, if you choose to think of it in terms of milestones and dream endings. It’s all a matter of framing—what you include, what you leave out, and how you choose to account for all the stuff you can’t possibly know.

At the moment he leaves the NFL, Manning has never seemed more human. That’s not a dream ending, and it’s not a particularly satisfying one. It’s what happens when you zoom in on someone’s life, and you realize that you don’t know much at all about someone you thought you knew so much about.