“You had to understand,” Fritz Pollard Jr., the son of the NFL’s first black quarterback, once told an interviewer. “You had to play within certain perimeters.” He was talking about the boundaries imposed on a popular black athlete negotiating public life in the 20th century. His father was 18 on the day the country threw the Mann Act at Jack Johnson, and by the time Fritz Pollard had achieved a measure of fame for himself, as a player and coach in the American Professional Football Association, he knew well the margins of permission granted any black athlete.

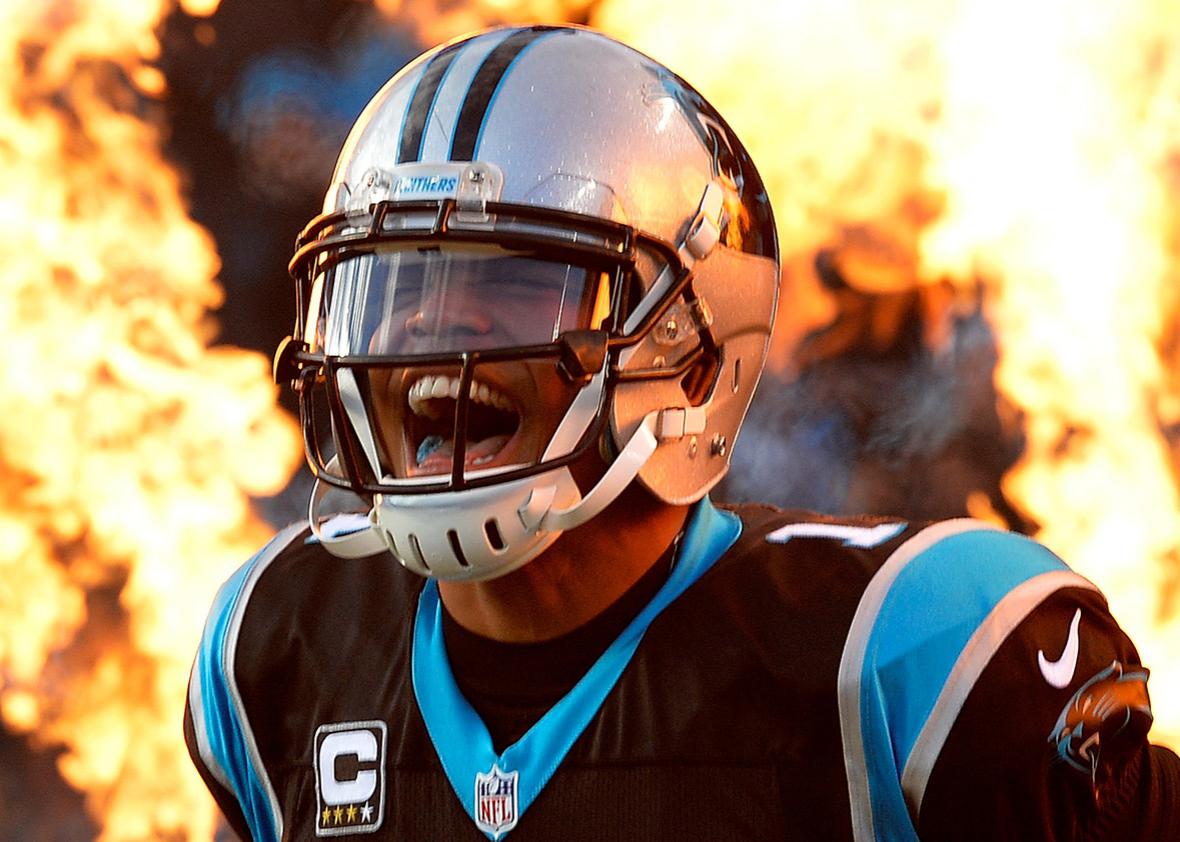

The son of the NFL’s first black quarterback was describing a sort of redlining of the imagination. I think of Pollard when I watch Cam Newton, the Carolina Panthers star who is having maybe the most compelling season of any black quarterback in history and who, smiling and dabbing and wearing Liberace’s piano on his feet, remains for still too many a figure who conjures clammy demographic anxieties. And yet, when I watch Newton, I see the old perimeters moving.

Fritz Pollard played some 90 years before Cam Newton’s NFL debut. He wasn’t a quarterback as we understand the position today, and neither for that matter was professional football anything like the professional football of today. But there was something timeless about those perimeters, particularly as they pertain to black quarterbacks.

“Black athletes could succeed in the white-dominated athletic world,” wrote John M. Carroll in his book about Pollard, “but only if they abided by an unwritten code of conduct both on and off the playing field.”

The code applies to all sports, to varying degrees. You can be black and prideful, but only to the extent that you’re willing to play the heel (Barry Bonds). You can be black and demonstrative, but only to the extent that you’re willing to play the clown (Chad Ochocinco). Your flaws as an athlete are racial traits, and your physical “gifts” are, too, and your success is a matter of how effectively you transcend your brute atavisms and embrace the prevailing “white” idioms of play (Donovan McNabb, Michael Vick, even Michael Jordan). You will be loved if you win often and win quietly and if all the while you hold yourself in such a way that you stand in exquisite contrast to the black athletes who lose too often or win too loudly (Kevin Durant, Joe Louis).

The code asserts itself like this: “Very disingenuous—has a fake smile, comes off as very scripted and has a selfish, me-first makeup.” Nolan Nawrocki’s infamous 2011 scouting report on Newton was no dog whistle. Subtler prose has been written on notes wrapped around bricks. “Always knows where the cameras are and plays to them. Has an enormous ego with a sense of entitlement that continually invites trouble and makes him believe he is above the law—does not command respect from teammates and always will struggle to win a locker room. … Lacks accountability, focus and trustworthiness—is not punctual, seeks shortcuts and sets a bad example. Immature and has had issues with authority. Not dependable.”

And it works like this: In a November game in Nashville, Tennessee, Newton salted away the Titans with a late touchdown on one of those trademark quarterback keepers wherein he seems not so much to run but to roll downhill, waving the football in one big hand the way Walter Payton used to. He celebrated by dancing in the end zone, prompting one “Tennessee mom” who’d attended with her 9-year-old daughter to write an oh-my-stars-and-garters letter to the Charlotte Observer. “Because of where we sat, we had a close up view of your conduct in the fourth quarter. The chest puffs. The pelvic thrusts. The arrogant struts and the ‘in your face’ taunting of both the Titans’ players and fans. We saw it all.” The letter continues:

My daughter … started asking questions. Won’t he get in trouble for doing that? Is he trying to make people mad? Do you think he knows he looks like a spoiled brat?

I didn’t have great answers for her, and honestly, in an effort to minimize your negative impact and what was otherwise a really fun day, I redirected her attention to the cheerleaders and mascot.

It would be hard to argue that the Tennessee mom captured the national mood. She came off more like a holdout in a culture war long since ended, an old soldier bustling out of a cave with fixed bayonet, blinking in a new day’s sun. So many people rushed to Newton’s defense that it became clear the whole second-act-of-Footloose argument over ecstatic celebration in sports had already been won, and that the scowling tight-asses had assumed the minority position. (Newton’s backup, a white guy named Derek Anderson, called the letter “flat-out racist.”)

After Newton’s gentle response to the note—he has a singular talent for retail politics—the Tennessee mom rowed back her initial sentiment. In an email to the Charlotte Observer’s Jonathan Jones, she wrote: “I am sorry I didn’t understand him better until this week. It is clear from his remarks that he recognizes his leadership role, both on and off the field, and that he truly cares about the kids watching him. I respect his comments just as much as he did mine, and I wish him nothing but continued success on the field and in life.” (Here we note that the Tennessee mom, a woman named Rosemary Plorin, is employed in the field of crisis communications.)

Nothing seems to stick—not for long, anyway. The code is typically never more austere than when applied to black quarterbacks, a signal-caller being the emissary of his coach’s will. But Newton keeps moving the chains.

In the past year or so, he has been ripped in some quarters for having a child out of wedlock. He has been criticized for openly aspiring to be an “entertainer and icon.” He has been filleted for telling a TV reporter, “[S]o much of my talents have not been seen in one person,” even though it happens to be true. But all of this, too, felt like an old culture war instinct—reflexive pandering by the media to a wave of disgust that never quite arrived.

The criticism about his kid amounted to two letters to the editor in the Charlotte Observer, one of which, to judge by the accompanying photo, was likely sent via Pony Express. Two letters is no more indicative of the public mind than are the piles of letters every newsroom in America receives daily about water fluoridation. Likewise, the “entertainer and icon” bit has gone dead, in part because the Panthers are winning and in part because the criticism was so plainly disingenuous, having originated with writer-brands like Peter King who often moonlight on television. (This is a minor hilarity that I’m sorry will never reach King in his redoubt deep within Roger Goodell’s anal cavity.)

The heaviest thing you can say about Newton is that he is “polarizing,” as ESPN did recently in an excellent profile. “He’s not a quarterback; he’s a Rorschach test,” Tim Keown wrote. But this elides something unique about Cam Newton’s appeal that helps explains how he has become, in Tom Brady’s twilight and Peyton Manning’s senescence, the grinning new face of the NFL. If he is not all things to all people, he at least has something to offer everyone.

In Cam, you find the stories of so many black quarterbacks who came before him. You find Fritz Pollard, sure—an entertainer and icon in his own right. But you also find Marlin Briscoe, an accused malcontent. You find Joe Gilliam, a clever operator who supposedly ran a slow 40-yard dash in a preseason workout, lest his coaches get the notion to convert him to a wide receiver or cornerback. You find Warren Moon, who also had to fight to remain a quarterback. (The University of Georgia recruited Newton to be a tight end.) You find Randall Cunningham, criticized for his flashy wardrobe, criticized for comparing himself to the likes of Michael Jordan and Wayne Gretzky—Randall Cunningham, who for so much of his career was reckoned a disappointment because he refused to plant his ass in the pocket, like any supposedly sensible quarterback.

And you find Joe Lillard, arrogant, haughty, hated even by some of his own teammates, a guy who likewise ran afoul of the amateurism mall cops during his brief time at Oregon in the 1930s. Lillard was once urged by a black columnist to “learn to play upon the vanity” of white people, for the sake not only of his career but of the cause of integration.

This is the triumph of Newton’s season: He is the first black quarterback to run seemingly afoul of those vanities and not only get away with it, but reconcile them with a “black” style of play. This could only have happened in the context of a year like this one, in which Newton was reckoned to have improved the stereotypically “white” aspects of quarterbacking—accuracy, pocket awareness, and the like—while leading his team to within a few points of a perfect season. (Watch this play, though, and tell me how you could even begin to untangle his athleticism from his intelligence.)

But Cam Newton didn’t observe the code; he made the code observe him. When the grouching over his end-zone dance commenced, this is what he said: “I heard somebody say we aren’t going to allow you to do that, but if you don’t want me to do it, then don’t let me in. I just like doing it. It’s not to be boastful. From the crowd’s response, they like seeing it. … No disrespect to anybody, it’s just a Panthers thing.”

Everyone loved it. He was talking about winning. He was talking about the team. Prideful and demonstrative, but neither the heel nor the clown. He was respecting the perimeters, but somehow he was dancing within them, too.