The realization that the Soviet Union hadn’t evolved as much as Mikhail Gorbachev suggested quickly dawned on Raycom Sports Chairman Rick Ray during a trip to Moscow in 1988. He was there to meet with a Soviet state sports committee, and the luggage belonging to him and Dee, his wife and business partner, got “lost” at the airport. Fortunately, a woman was there to escort them, and he explained to her the problem. Within about 20 minutes, she had taken them past a bevy of security guards to a storage room stacked high and wide with other “lost” items. Ray thought it resembled the cavernous storage facility in Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark.

They found the luggage. Everything was fine. As for the woman, Ray decided immediately: She wasn’t just a tour guide. She was a KGB agent. “We were sure she was reporting back everything,” Ray said. “She would check all our phone calls and look over the documents. She could get in everywhere.”

And all of the apparent trouble was for a college football game.

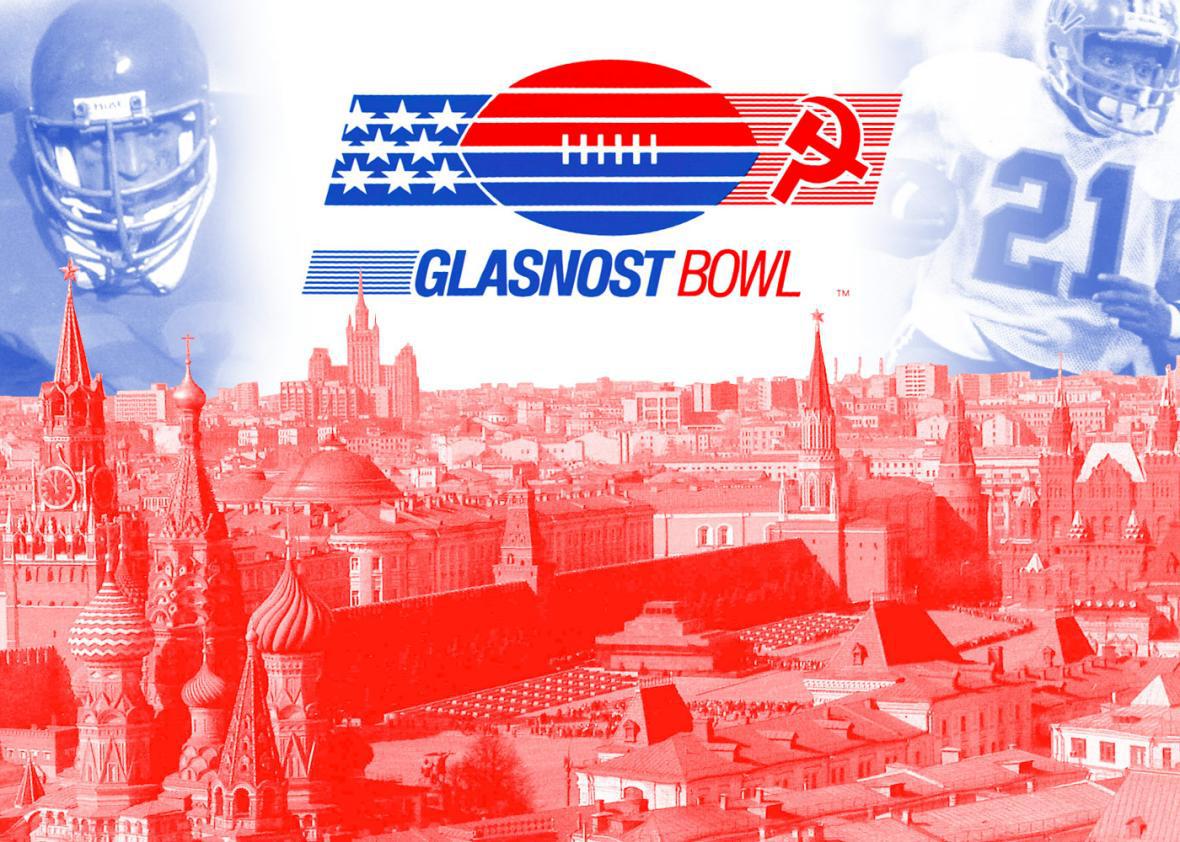

These next few weeks of bowl season promise novelty and weirdness from odd-sounding sponsors (the Zaxby’s Heart of Dallas Bowl) to exotic locations (the Popeyes Bahamas Bowl) that have become commonplace in college football. In the future, a bowl game in Dubai is possible, and Cal and Hawaii just announced they’ll play in Australia at the beginning of next season. But no game could compare with what Ray was trying to put together during that 1988 trip. His company, Raycom Sports, had brokered a deal with the Soviet Union to host a 1989 season-opening game between the University of Southern California Trojans and the University of Illinois Fighting Illini that would be called the Glasnost Bowl. It came at a time when the Cold War was finally starting to thaw, with the Berlin Wall still standing but Gorbachev pushing for perestroika and glasnost. Sports were a small part of his plan. The Glasnost Bowl was to be the first official football game played in the Soviet Union, and it was expected to become an annual tradition. Raycom even entertained a remote dream of getting Ronald Reagan to do the coin flip. And the game itself was actually seriously looking like it was going to happen! That was until the 1980s version of what came to be known during the last Olympics as “Sochi problems” (Russia’s sometimes shockingly backward infrastructure) became clear, and everything fell apart.

In the fall of 1988, Raycom was close to sealing the sports deal of the century. The sports marketing company was offering the Soviets the promise of a financial windfall if they agreed to host the game and even received support from the United States’ vice president: George H.W. Bush expressed his excitement about bringing football to the Soviet Union in a letter to the Soviets. “It was like the pope had endorsed you,” Ray said. “It was crazy.”

Yet even with the support of Bush, the Soviets were unwilling to commit after several rounds of negotiations. It ultimately took what Raycom considered to be counter-espionage measures to get the Russian officials to agree to a deal. Ken Haines, then the vice president of Raycom and now the president and CEO, believed their phone calls were being tapped in Moscow. So on a call between him, Ray, and Dee, they feigned like they were getting the short end of the negotiations and said they hoped the Soviets wouldn’t accept. This bit of attempted reverse psychology seemed to have worked. “We got it signed in like half an hour,” Haines said.

ABC agreed to televise the game, and deals were made with other networks for it to be broadcast in the Soviet Union and Western Europe. The Glasnost Bowl was expected to be one of the most-watched football games of all time.

USC and Illinois were selected from a pool of about 15 teams. Illinois was coached by John Mackovic and led by future No. 1 NFL draft pick Jeff George at quarterback. USC had future NFL Hall of Famer Junior Seau and “Robo” QB himself, Todd Marinovich. The preparations were so serious that to get Marinovich and the other players ready, USC offered them conversational Russian classes.

On the other side of the world, Ray was doing everything he could to prepare Moscow and the Russians for a sport most knew nothing about. (During one of at least five trips to Moscow to sell the Russian officials on the idea, their first question was, “How many players are killed in a game?”)

In Russia, Ray and others working to make the Glasnost Bowl happen experienced dramatic, almost comical cultural differences that demonstrated how closed off Soviet Russia still was at the time. During one visit, his and his wife’s room had cockroaches. Ray complained to a manager about bugs. What he says happened next has the ingredients of a bad Yakov Smirnoff joke: The hotel workers assumed by bugs that he meant recording bugs. Ray and Dee were transferred to another room with more cockroaches but presumably fewer recording devices. USC athletic director Mike McGee and his wife, Ginger, booked a room specifically overlooking Red Square during their scouting trip so they could watch a May Day Parade. They were viewing it through the window, holding cameras, when troops started marching in the parade. All of a sudden, four or five soldiers charged into their room. “They went over to the window,” McGee told me, “and pulled the window shut and the screen down and said, ‘Nyet!’ ”

These difficulties for actual officials would be a harbinger of the problems for fans that would ultimately doom the Glasnost Bowl. When the game was announced, 3,000 Americans had bought travel packages from Raycom to come to the game, and 1,500 hotel rooms were needed. But the Soviet Union wasn’t able to offer them. Round after round of negotiations with unions, civil organizations, and local governments got Raycom nowhere. By the end of these negotiations, Ray couldn’t tell who was in control of individual hotels, much less guarantee reservations for the rooms. Raycom Sports called off the Glasnost Bowl about two months before the game was scheduled to take place.

USC and Illinois had to settle for a game at Memorial Coliseum in Los Angeles. The Soviets had to settle for Oklahoma high schoolers. Two all-star teams made up of kids from throughout the state visited the country later that year and played the first official football game in the Soviet Union.

Haines gets phone calls every so often from academics who are curious about how Raycom attempted to plan the Glasnost Bowl. He regrets that the game got canceled and hoped it would showcase friendlier relations between the two countries. While the bureaucratic Soviet government wasn’t ready to host a one-off college football game, Haines is confident the Russian people would have embraced the pageantry of the sport, had they only had the chance.