Ideally, one part of the brain—commonly known as “the understanding”—limits the psychic distortions of sports viewing to a civilized minimum. If my Facebook feed is any indication, the balance between healthy fanaticism and clinical psychosis—on the part of some otherwise nice people—has been tipped in an alarming direction. This is thanks to “deflategate”: the case of the New England Patriots and the allegedly intentional deflation of footballs.

Over the years, Patriots fans have learned to treat every feature of reality as fluid in order to hold two variables—Bill Belichick is the greatest coach who ever lived, and Tom Brady the greatest quarterback—absolutely constant. With the release of the Wells Report—the NFL’s 243-page report laying out the case that footballs were tampered with—the condition has gone code red.

To Pats Nation, “you hate us cause you ain’t us,” or, in English, any criticism of the franchise is sour grapes; the Wells report has been debunked; Spygate was trumped-up nonsense; the fumble statistics indicating the franchise has been advantageously deflating for years are a mess; the Pats would have beaten the Colts anyway; and the team is the victim of a witch hunt. To get a fuller picture of how fandom can bend an otherwise normal psyche in the direction of wishful thinking, selective memory, and situational ethics, let’s look at these claims one by one and in reverse order.

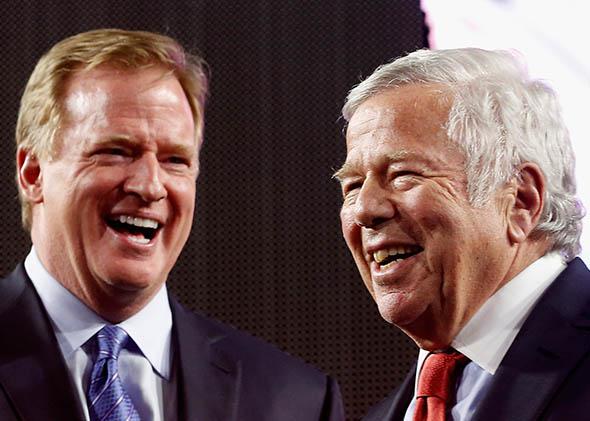

The Patriots are the victims of a witch hunt: To believe this, you have to believe the sport’s commissioner, Roger Goodell is intent on singling out the franchise, painting it in the worst possible light and, while rallying the media and the public to his side, excessively punishing it simply for being smarter, better coached, and more disciplined. To believe that, you have to ignore ample evidence that Goodell’s interests lay in precisely the opposite direction, starting with his one-time friendship with Patriots owner Robert Kraft.

Here is how Sports Illustrated recently described the relationship between Kraft and Goodell:

Kraft in many ways made NFL commissioner Roger Goodell. Kraft helped push through Goodell’s election in 2006. Five years later, Kraft left his ailing wife, Myra, to convince the players that Goodell, who was widely despised, and the league could be trusted in negotiations for a new collective bargaining agreement. Kraft helped promote and justify Goodell’s salary increase from $11.5 million before the 2011 lockout to an average of $37 million over the last two fiscal years. And in the wake of last year’s Ray Rice debacle, Goodell’s darkest hour, Kraft defended Goodell to the public and worked behind the scenes to make sure other owners remained loyal to the embattled commissioner.

As the article goes on to note, the Pats “generated the most complaints to the Competition Committee during the Bill Belichick era, and many team executives felt the issues raised were swept under the rug.” As Seattle Seahawks cornerback Richard Sherman colorfully pointed out before his team faced the Patriots in the Super Bowl, Goodell was a guest at Kraft’s Brookline home the very day of the deflategate game. As GQ reported, one NFL executive even nicknamed Kraft “the assistant commissioner.”

We would have beaten the Colts anyway: This is demonstrably true, and completely irrelevant. Cheating tosses counterfactuals out the window. It doesn’t matter how good Roger Clemens, Barry Bonds, Lance Armstrong, etc. would have been without synthetic enhancement. The use of prohibited advantages forfeits the claim to intrinsic excellence. If my child cheated on an exam then claimed she would have “pulled an A anyway,” I’d double the length of her grounding.

You don’t have to look hard to find a 2014 playoff opponent the Patriots did beat by a slim margin. One week before dominating the Colts, the Patriots edged the Ravens by four points—a thriller in which one turnover might have made the difference. A deflated football is easier for a quarterback to grip, of course, but also apparently harder to fumble. Which brings us to …

Those fumble statistics are a hopeless mess: In the immediate aftermath of deflategate, a blogger named Warren Sharp posted a homegrown analysis, in which he attempted to demonstrate that the Patriots fumble rate since 2007 has been a statistical outlier on the low side. (Slate, among other outlets, republished this study when it first appeared.) Why was this important? As Sharp pointed out, in 2006 Tom Brady led a campaign by NFL quarterbacks to gain pre-game control of their footballs. In March 2006, the NFL Competition Committee agreed. It was after this rule change, Sharp pointed out, that the Patriots’ fumble rate dropped dramatically.

Sharp’s analysis suggested the Patriots, and not just Tom Brady, derived an enormous, and not just a marginal, advantage from a deflated football. The study immediately came under withering attack. Sharp is an engineer, not a statistician, and he didn’t account for every variable. But Sharp’s rejoinder is hard to answer. Regardless of how much of an outlier the Pats’ fumble rate is, it declined, declined significantly, and did so after the rule change.

Hypernumerate sophisticates have demanded this study be chucked. (Oddly, many of these hail from New England. Paging Thomas Bayes!) But when a writer for Nate Silver’s esteemed data journalism site FiveThirtyEight looked at it again, he wasn’t so sure. “Though it had flaws,” Benjamin Morris wrote, Sharp’s study “correctly identified that the Patriots fumble rate has been absurdly small. I did my own calculations using binomial and Poisson models and found the same.” Brian Burke, an occasional Slate contributor who is a trusted and respected source on NFL stats, agreed that there was something to the argument that Pats’ fumble stats got really good in 2007.

Sharp’s analysis may have overstated the precise degree to which the Pats’ fumble rate is an outlier, as Slate’s Jordan Ellenberg found when he re-ran the numbers. But if the team’s fumble rates plunged after Brady got his rule change—and it did—that gun still smokes. The Patriots’ fumble rate in light of deflategate “makes it more likely that the relationship between inflation levels and fumbling is real—and more likely that the Patriots have materially benefited from their cheating,” as Morris concluded.

Spygate is trumped-up nonsense: Spygate provides the basis for the severity of Goodell’s deflategate punishment; it is data-point No. 1 for believing the Patriots are serial cheaters. Who wants to relive Spygate? Nobody. Which is what Pats fans are counting on when they claim that, in videotaping opposing coaches’ signals, the Pats did nothing wrong.

But there was more to Spygate than NFL fans want to recall. Here’s the basic outline: The NFL rulebook has an unambiguous ban on sideline videotaping. The league sent out a memorandum prior to the 2006 season, emphasizing its rule banning video recording. On Sept. 9, 2007, in the Pats season opener, security officers seized a sideline video camera used to steal coaches’ signals from the team’s opponents, the New York Jets.

The Patriots, it turned out, had been signal-harvesting under Bill Belichick for a while. Their video trove included at least one tape from a playoff game in their 2002 Super Bowl run. Matt Walsh, the Patriots videographer, later claimed that he made nearly a hundred “cut-ups” per game—that is, signal-steals converted into video snippets. These were allegedly cataloged, then used in-game to predict formations and plays; these predictions were sent via radio signal into Tom Brady’s helmet. In no uncertain terms, Walsh claimed to HBO’s Real Sports With Bryant Gumbel that the team organization knew what it was doing was wrong; that it took pains to hide it; that it was advantageous; and that Bill Belichick was fully complicit.

Why should we believe Walsh? After news of Spygate broke, Walsh hid from the media out of fear of litigation. Walsh came forward only after Sen. Arlen Specter forced the issue, and the Pats and the NFL signed an indemnity agreement with Walsh. The agreement was fragile: If Walsh uttered a falsehood, its protections were negated. Parties signed in late April 2008. Walsh was interviewed by HBO and revealed the above information at the beginning of May.

For taping opponents’ coaches and thereby stealing their signals, Roger Goodell found the Patriots guilty of “a calculated and deliberate attempt to avoid longstanding rules designed to encourage fair play,” then levied what were, at the time, the severest penalties in the history of the sport. Was this unduly harsh? Tuck away your persecution complex, Pats Nation. Goodell punished the Patriots without seeing the tapes; his surrogates reviewed the tapes in the Patriots’ own facilities in Foxboro, Massachusetts, not at NFL headquarters in New York; they then destroyed all the evidence on site, before anyone else could review it.

Pats fans want to believe Belichick took advantage of a gray area in the rulebook: He derived no important benefit from it anyway, and the punishment did not fit the crime. The truth is, the Patriots violated a black-and-white rule; they gained an anti-competitive advantage doing so; and they were lifted off a much sharper hook by a commissioner looking to make the scandal disappear.

The Wells Report has been successfully rebutted: The Patriots “rebuttal” to the Wells Report is a public relations document aimed more at Chuckie Sullivan than any finder of fact. Setting aside its more obviously asinine hypotheses, its overall strategy is plain: To take each piece of evidence and isolate it from any context, then show how standing alone it proves nothing. The report as a whole adds up to a Bayesian nightmare for the Patriots—that is, regardless of how individual facts can be construed, together they point to a single inference: Patriots employees knowingly tampered with game-day footballs.

Ignoring distractions (a Pats’ employee nicknaming himself the “deflator” only in reference to weight loss), let’s take the most important details one at a time.

A Nobel Prize winner disputes the science of the Wells Report: I note without comment that the esteemed laureate is a neurobiologist whose work is unrelated to ideal gas theory. He is, however, the founder of a startup company, one of whose principal investors is “the Kraft Group,” according to the Boston Globe.

The Patriots were fully cooperative and only denied an absurd fifth interview request with Jim McNally, the so-called “deflator”: After an initial set of interviews with NFL security—during which McNally’s story shifted suspiciously—the NFL hired Ted Wells to supervise a formal investigation. Wells wanted to interview McNally for a second time after discovering the “deflator” text. He offered to meet McNally anywhere, and anytime. Attorneys for the Patriots refused.

Tom Brady gave nothing of special value to the deflategate flunkies when he handed them autographed memorabilia: McNally didn’t receive any ordinary headshot scrawled with magic marker. McNally—with Brady present—was handed a signed, game-worn Tom Brady jersey. A similar jersey sold for more than $45,000 in 2012. John Jastremski, meanwhile, proudly claimed he was in possession of the very ball Brady threw to surpass the historic 50,000–yard mark, though he later said he was lying about that.

Three of the four tested Colts balls were also in violation of the psi requirement: On three of eight measurements, the Colts balls were fractionally lower than the required 12.5 pounds per square inch (psi), and at exactly the level anticipated by the Patriots’ own deflation theory—i.e., that starting out in a locker room and getting colder outdoors can marginally shrink a football. Eleven Patriots footballs on all 22 measurements, meanwhile, were well below regulation psi. None of the gathered referees and none of the summoned senior NFL officials—not one—thought any of the Colts footballs needed a single puff of air to be certified for second-half play. In sum: Every Colts football was legal; every Patriots football that was tested was illegal.

Referee Walt Anderson is unsure which of two gauges he used to measure psi of the footballs prior to the AFC Championship Game kickoff. Of the attempts to throw sand in the public’s eyes, this is the only one that is at all jury-worthy. (Though not, I think, arbitrator-worthy.) Whichever gauge Anderson used, he is adamant that the Patriots pre-game ball was at 12.5 psi, and the Colts ball closer to 13—exactly in line with each team’s stated preference. The two gauges in question, however, were slightly “off” relative to one another—one consistently read 0.3 to 0.4 higher psi than the other. It is very likely Anderson used the more accurate gauge, as he firmly recalls the footballs as set at the team’s preferred psi. (To believe he used the “off” gauge, you’d have to believe it was “off” to exactly the same degree as both the Pats and the Colts’ own gauges, used to set footballs precisely to their respective quarterbacks’ liking.)

But it doesn’t matter which gauge Anderson used. It doesn’t matter because the Wells Report ran the numbers both ways. Both times its hired quants came up with a statistically significant difference between the drop in pressure of the Patriots balls relative to the drop in pressure of the Colts balls. Under both scenarios, that “delta” is not explicable by gas theory, atmospheric conditions, or discrepancy in game use.

Any claim that the status of the Colts’ balls negates the status of the Pats’ balls ignores the following: Game officials had been warned ahead of time about the Patriots using deflated footballs; the Patriots footballs were in fact deflated; there are dozens of text messages between two Patriots employees referring to deflating footballs; one of these employees initially lied about the eventually deflated footballs’ chain of custody (a protocol violation at the time struck the head referee as alarming); the employee subsequently lied about his whereabouts; alternative to intentional deflation, there is no explanation for the fact that Patriots footballs were more deflated than Colts footballs, or none that has survived repeated testing.

Finally, the entire argument boils down to: You hate us cause you ain’t us.

No Pats Nation, I’m sorry. I do not hate you because I ain’t you. I just prefer living in a world where the normal canons of observation and inference still abide. However, I do hate you. And here is why.

In an age of nuclear umbrellas, the majority of men do not fight wars. In the age of deindustrialization (and off-shoring, and soon enough, advanced robotics), American men, at least, do less and less heavy lifting. As brawn phases out of everyday life, it becomes ritualized, vicarious. Of course football has its celebrated chess-like aspects, but the game’s primal appeal is in the physical domination of some men by some other men.

In recent years, watching NFL games has gone from being a thinking person’s harmless diversion to a kind of embarrassment, and that embarrassment is only getting worse. The game is brutal, possibly lethal, to combatants. However, as this fact becomes clearer, the sport only becomes more popular. Where is the breaking point, separating a relatively anodyne bloodlust from a total lack of self-respect?

Who knows, but here is one theory: As brawn has exited everyday life, it’s been replaced by a new, and to my mind, sinister form of machismo. You could say the archetypal figures in this New Economy of machismo are: The crybaby mogul, who throws a fit whenever he doesn’t get his way (and sometimes when he does); the upper management guru who is hailed as a genius though he is simply a cunning rule-breaker; the superstar whose smirk is in proportion only to how dependent his performance is on the machinations of the mogul and the guru. Over all this presides the figurehead droning on about “integrity.”

People turn on the NFL as a relief from this economy of sinister machismo, whose worst effect is, after all, turning truth into the handmaiden of power. They turn it on to see something unmistakably true—to see old-fashioned brutality, lightly veneered with tactical cleverness. If in seeking escape they only find more of what they’re escaping from—more field-tilting, more corporate jingoism, more doublespeak—they will, improbable as it may seem now, abandon the NFL.

Ever since the first mother counseled it was so, it has been comforting to believe people hate us only out of envy. I’ll conclude by repurposing an old quote from Edmund Burke, who about patriotism once wrote: “To make us love our country, our country ought to be lovely.” One might say about Patriotism: Some things are hated simply because they are hateful.

P.S. Go Jets.