A version of this essay was originally printed in the Iowa Review.

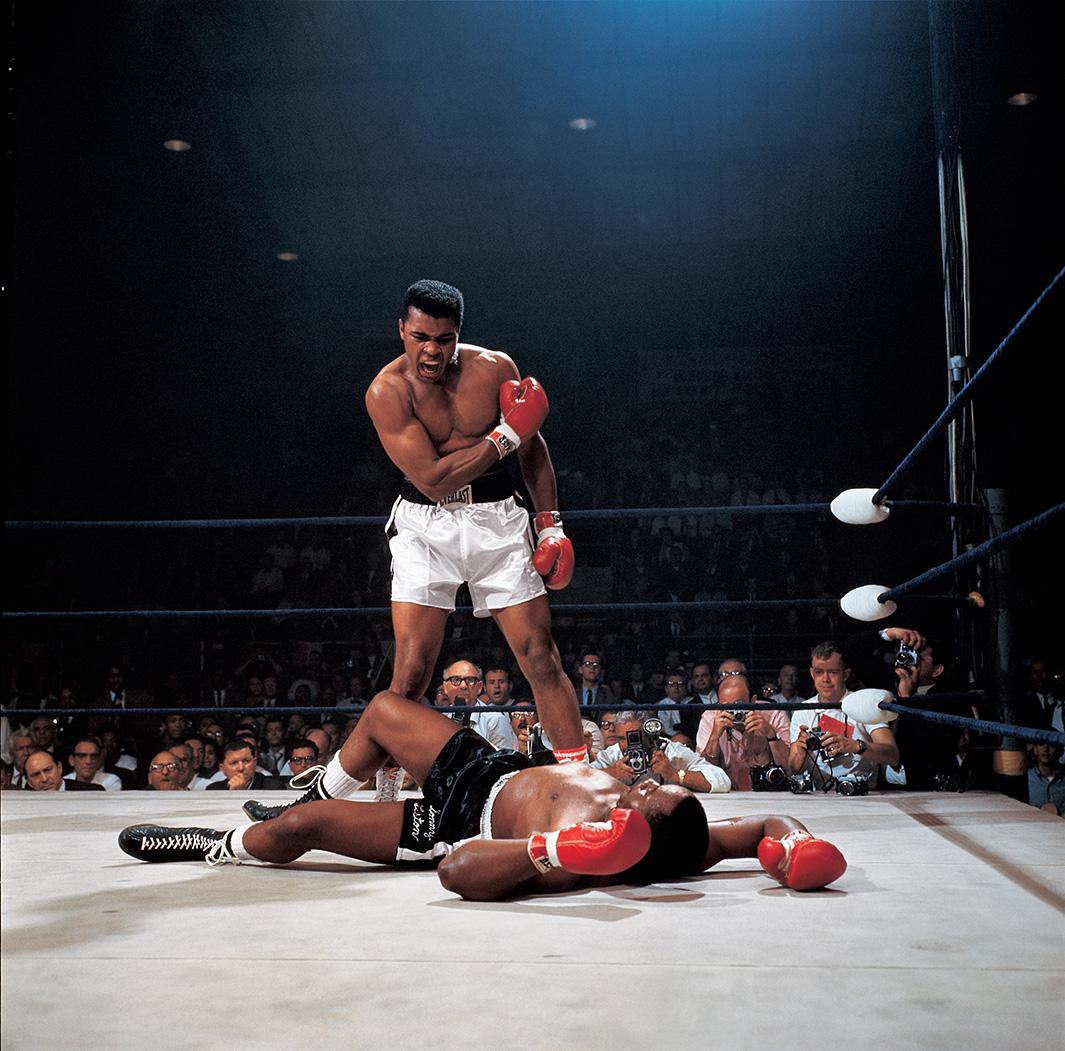

Sonny Liston landed on canvas below Muhammad Ali’s feet on May 25, 1965, and Neil Leifer snapped a photo:

Photo by Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

Afterward, several events unspooled:

The photo languished unlauded—before it was (much later) recognized as one of the greatest sports photos of all time; Ali became the most hated figure in American sports—before he was (much later) named “The Sportsman of the Century”; and Liston was subjected to intense scrutiny—before (not much later) he fizzled into a mostly forgotten footnote.

Like many sports fans, I’d glimpsed this picture for years—in random Ali articles, atop “best of” lists, even on T-shirts—but it wasn’t until doing my own research, excavating layers, that I discovered its most astounding attribute:

Everything you’d initially imagine about the image is wrong.

But first, just look at that photo! It instantly hits your eyes haloed in a corona of potency—structured so soundly as to seem staged, this forceful frieze of physical dominance. The Victor yells, the Loser displays himself vanquished, and the Watchers are all caught in that moment. The kinetic poetry of moving bodies, momentarily frozen, such is the stuff of the best sports photos—this has that.

There are also the incongruities! The Victor, appearing to proclaim dominance, is in fact pleading for the bested man to rise; and, for that matter, there is secretly a second bested rival below Ali; and though this looks like the moment after a vicious put-down punch, the photo was actually preceded by the puniest of blows, a “phantom punch,” as it would later be known—a wispy, theoretical mini-hook that none in attendance even observed. That Crowd so multitudinous that it stretches beyond the horizon line? They were actually the smallest assembled crowd in heavyweight championship history—there to witness a bumbling conclusion, filled with calls that the fix was in. This bout: still boxing’s biggest unsolved mystery. This image: still iconic, even (especially) with the controversy, for a sport as mythologized as it is crooked.

The Photo

Neil Leifer must have been crestfallen.

He snapped the shot of the bout—knew it—but could only watch while other photos filled the prominent pages of Sports Illustrated, his own work failing to make the cover.* Leifer must have been crestfallen because he’d taken an artistic risk that night in May. Specifically, he went out and loaded Kodak’s latest Ektachrome film into his Rolleiflex medium format—which is an overly technical way of saying that Leifer was shooting in color.*

Leifer was known for excessive preparations, but however early he’d arrived to the fight, he didn’t have his pick of seats. Herb Scharfman, a senior photographer at Sports Illustrated had the first pick and wanted the spot by the judges’ table—it made for easier midnight maneuvering. Leifer, the 22-year-old striver at Sports Illustrated, chose the opposite side.*

To capture the color, Leifer had rigged special flash units over the ring, but this led to another, bigger challenge: Leifer had one shot. The other photographers brandished the equivalent of semi-automatics while he held a sniper rifle. Leifer’s strobes needed time to recharge, which meant he couldn’t click and click. Whenever a fighter fell, the other photographers could quick-twitch their shutters, but Leifer had to pick one moment, artistically aping the sniper’s motto: one shot, one kill.

Nonetheless, Leifer managed the risks and got the great shot—got it, knew it—but couldn’t get it to stick. Eventually, many months after that issue of Sports Illustrated had been consigned to the stacks, Leifer submitted it to the prestigious “Pictures of the Year” contest, but there, too, the photo failed. What would later be selected as the cover for Sports Illustrated’s issue on “The Century’s Greatest Sports Photos” couldn’t conjure an honorable mention.*

* * *

“Luck in sports photography is everything,” Leifer would say later, “but what separates the really top sports photographer from the ordinary is that when they get lucky, they don’t miss.”

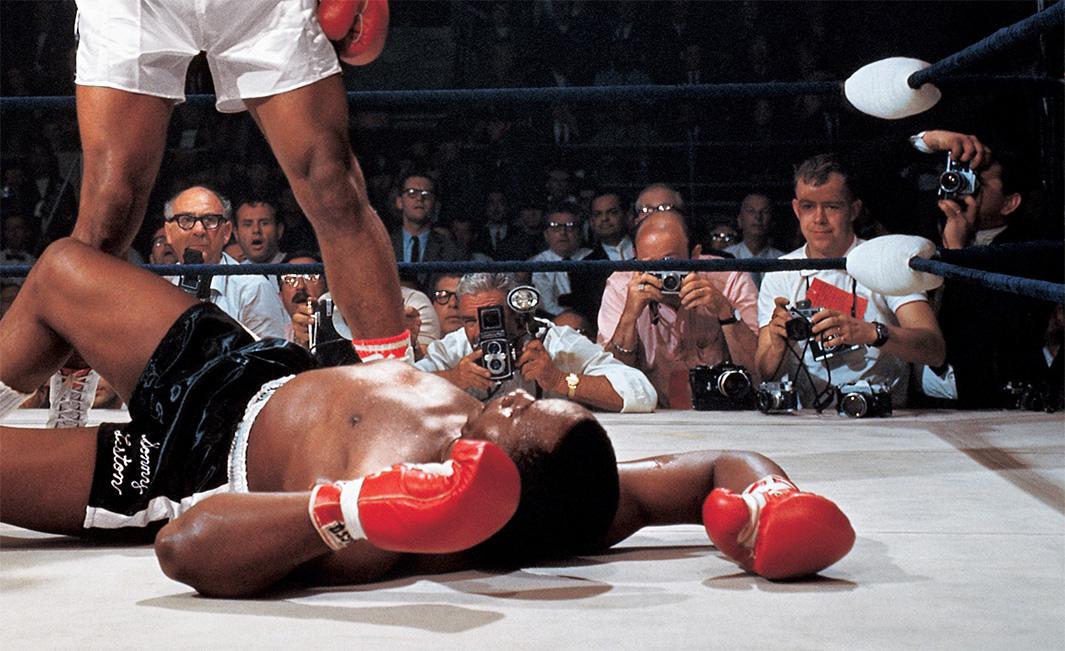

Leifer didn’t miss that day, and he also got lucky. If Leifer hadn’t chosen the opposite side as Scharfman, he would’ve been stuck shooting toward Ali’s back at the big moment.* But when Liston fell, he fell in front of Leifer, not Scharfman. “It didn’t matter how good Herbie was that day,” Leifer said. “He was in the wrong seat.” Instead of snapping a historic photo, Scharfman became part of one. The balding man between Ali’s legs? That’s Herb Scharfman, Leifer’s rival:

Photo by Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

But Leifer wasn’t just lucky. Sitting near him on fight night, also on that lucky side, was an AP photographer, John Rooney.

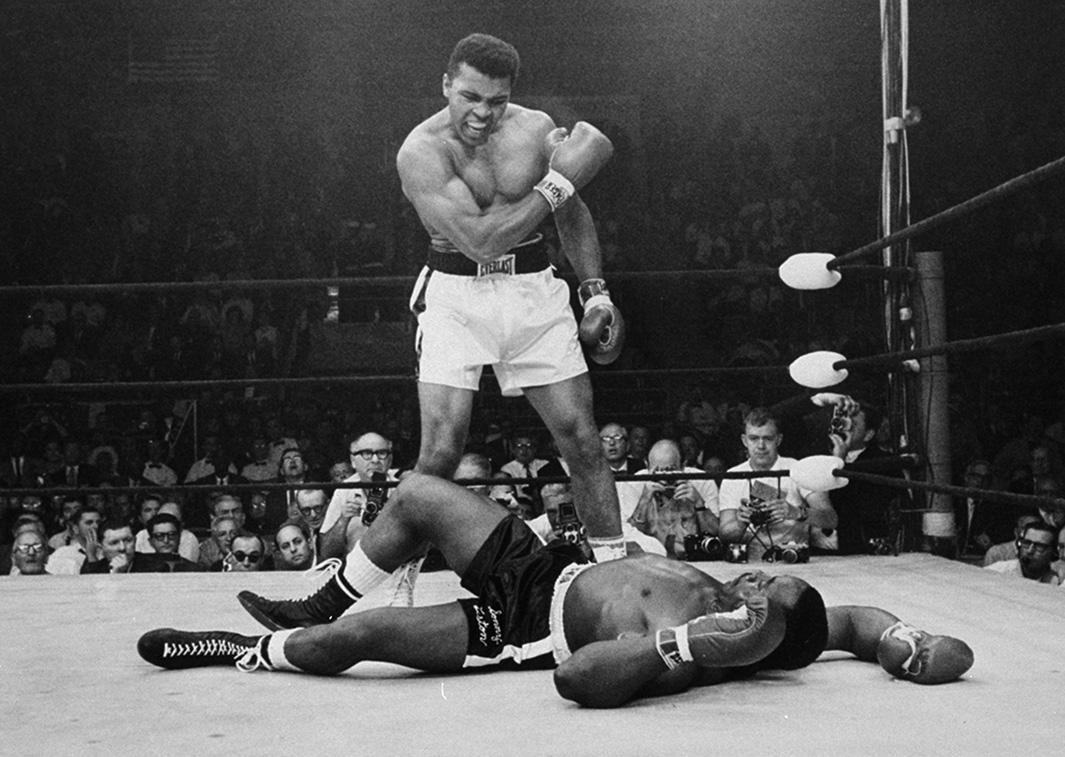

Rooney had almost the same position as Leifer and snapped this photo (note the difference by the location of Scharfman’s head):

Photo by John Rooney/AP

Not a bad photo at all—good enough, in fact, to go out on the wire and be featured on front pages throughout the country. But look at both pictures. What makes only one iconic? As noted by photography editor David Schonauer, it’s partly the color and clarity of Leifer’s Ektachrome over Rooney’s black-and-white Tri-X film. Similarly, there’s Leifer’s Rolleiflex camera, as opposed to Rooney’s 35 mm SLR—which is a jargony way of saying that Leifer ended up with a big square, not Rooney’s rectangle. The square is essential. Its solid structure supports, reflects Ali’s strength; more importantly, it captures the blackness above the man.

What is it about that space above Ali that seems to be the very difference between good and great? Rooney’s photo is cramped, quick; it delivers all its information immediately, forcefully. Leifer’s photo conveys the same power but lets us linger, our eyes allowed to stroll around the stage. That black blankness at the top of the photo lets us consider Ali within his world. He seems all the more strong, archetypal, for such space. Also, the center of the image is bracketed by Sonny Liston’s knee on one side and his eyes on the other, both aimed skyward. Our focus is drawn to the downed man, then shot back up to the victor.

But maybe such a beautiful image shouldn’t be overly parsed—like the E.B. White quote comparing comedy to a frog: To dissect it is to kill it. The genius might be as simple as Leifer’s timing. Once more, look at the two images—look at Ali’s expression. Such a slight change, telling us the photos were snapped milliseconds apart. Surely the superiority of Leifer’s moment is mere luck—no one could calibrate such a quick click, right? But those same semiseconds are the twitchy difference between hitting a home run or routine foul, between slipping a jab or taking it on the chin. We credit athletes for their split seconds—instinct helming the controls of consciousness—so why not the same for the folks photographing them? “Whether that’s instinctual or whether that’s just luck,” Leifer said when forced to conjecture, “I don’t know.” Sounds like the humble postgame evasion of an athlete.

Still, Leifer knew what he had when he saw it. “If I were directing a movie and I could tell Ali where to knock him down and Sonny where to fall, they’re exactly where I would put them.” And yet, however cinematically staged, recognition would wait. Rooney’s photo won the 1965 World Press Photo Prize for the best sports picture—though, now, Rooney and his photo are mostly forgotten. Indeed, when Rooney’s photo shows up online, it’s usually attributed to Leifer, assumed to be a black-and-white, cropped copy of the great, big original.

Leifer’s photo grew in fame slowly, only as Ali’s fame grew. Leifer attributes it to people’s admiration for Ali, after he was forced to forfeit the prime of his career because of his political activism. “This photo shows Ali at the height of his powers,” Leifer said. “People wanted to remember him at his best.” Leifer and Ali were alike in this way, both remembered for their professional heights (Leifer would go on to become one of the greats of his profession, making the cover of SI more than 150 times and the cover of Life more than 40), unlike poor Scharfman, a man known for much of his life as being at the very top of his profession, but now mostly noted—when noted at all—as the answer to a trivia question, a joke. The man between Ali’s legs. How aptly, then, he matches the man directly below him in the photo, Scharfman’s chin almost upon Liston’s thigh.

The Fighters

It’s hard to imagine a man more memorialized for being the opposite of what he was, at least for 95 percent of his life, than Sonny Liston. He was the most frightening, the most punishing boxer in over a generation. The sport had been in a slow swoon since the retirement of Rocky Marciano a decade prior, and though Liston didn’t have the properly pale pigment to capture the popular imagination like ol’ Rock from Brockton, Liston revived pugilistic passion in a new way: Everyone loved to hate him. Even in a sport defined by violence piled upon violence, Liston’s brutality stood out—both within and without the ring.

Liston was arrested and investigated by law enforcement numerous times, and, save for a few mob-connected money-laundering allegations, the arrests were all of the fists-on-flesh variety. In a famous incident, five cops jumped Liston, beating him about the head and neck until they “broke [their] hickory nightsticks”—and they still couldn’t get cuffs on him. In a more cartoonish infraction, Liston deposited a cop headfirst into a trash can. And there was the time Liston took away the gun of an arresting officer—Liston broke the guy’s knee, then strode from the scene wearing the copper’s hat.

Liston’s fists each measured 15 inches around. For reference, a slow-pitch softball can be 11 inches around; so take that softball and inflate it an extra third in size, stick that on the end of your wrist, and propel it forward with some of the biggest biceps on record—and then you can understand what Sonny Liston was slapping people around with. He had no trouble getting at those folks, either, with a reach of 84 inches, one of the longest in heavyweight history. Our understanding of adjectives dictates that a thing can be either long or squat, but Liston’s arms were somehow both—agile tree trunks, lithe railroad ties.

Such was his reputation that many heavyweights refused to fight him; he was the perfect frightening fighter to excite loathing in white crowds. But not just white crowds. When Floyd Patterson, the champ before Liston, finally agreed to fight Sonny, the NAACP tried to persuade him not to go through with it. They were afraid of the clichéd criminal image that Liston would present to Caucasian America.

But Liston went ahead and faced longtime champ Patterson and pasted him in the first round. Liston became the champ, though he’d always say the NAACP rejection really hurt him. A lot of things hurt the very private Liston that he didn’t let on about. For example, when he returned home to the proudly provincial Philadelphia, there was no celebration; the town hated him. A local scribe suggested, “Emily Post probably would recommend a ticker-tape parade. For confetti we can use shredded warrants of arrest.”

Liston was the 24th of 25 children. His father beat his children mercilessly. Though he didn’t like talking about it, when a trainer once asked him about all the scars on his back, Liston said, “I had bad dealings with my daddy.” In his early teens, Liston escaped to Chicago with his mother and boxed for their survival. He never learned to read or write. After his lack of acceptance after his title, buoyed by insecurities from a lack of education, he sunk further and further into his Mafia connections. At the time of the Ali bout, Sonny was living full-time in a Vegas casino connected, like his manager, to mob men. None of this endeared him to the populace, but it also didn’t make them lose respect for his power within the ring.

At the time he fought Muhammed Ali, Liston went off as a heavy favorite. No one was betting on Ali. He was a cocky kid who’d recently won Olympic gold in Rome, but at the time of the fight, he wasn’t even the second-rated fighter in the world. He could dance, he could dodge, but everyone knew he couldn’t take a punch.

Of course, he wasn’t Muhammed Ali then. He was a kid named Cassius Clay, highly untested, and the experts were right to doubt him.

Ali was nearly knocked out by British champ Henry Cooper in the fight right before the Liston bout. At the end of the fourth round, Cooper caught Ali with a cool, clean left (“ ’Enry’s ’Ammer” it was called in Britspeak), and down went Ali.

Tangled in bottom ropes, eyes rolled back—the bell rung just in time. Ali stumbled to his corner, slack on his stool, slapped by handlers. “Doesn’t know where he is!” the fight announcer exclaimed. Ali kept trying to open his eyes wide like a child mocking surprise, then sloughed off. The manager grabbed smelling salts (technically illegal under British rules), and then, finally, Ali snapped to. The bell clanged, and Ali floated mid-ring and simply sort of destroyed Cooper. Ali’s movements were loose and casual as he repeatedly, specifically punished a spot to the upper left of Cooper’s eye socket until it swelled grotesquely. Between sepia-toned camera shots in the original footage, you can see something in Cooper’s face break and blood go everywhere. Cooper threw his arms around Ali—blood streaks, smears on boxers’ chests—as the announcer said, “Appalling. That’s the worst cut eye I’ve seen.” Then the ref called it.

Ali was victorious. And yet, if ’Enry’s ’Ammer had landed 30 seconds sooner, it seems obvious that Ali wouldn’t have been saved by the bell. Which means he would’ve been knocked out. Which means he wouldn’t have been undefeated. Which means Ali wouldn’t have had the chance to face Liston, which means—pretty much—he never would’ve become Muhammed Ali.

Does this mean Ali wasn’t really one of the greatest heavyweights of all time? Nope. It just means that even in sports—where a person treasures the reduction of all the questions and complications of normal life to simple, finite numbers, easy to analyze—it turns out that luck is still uncomfortably king. As true for Ali as Leifer, Liston as Scharfman.

Nonetheless, Ali did get lucky, did get his chance, and he was ready—like in Leifer’s mantra, he didn’t miss his shot. On Feb. 25, 1964, Ali defeated Liston in seven rounds and stormed around the ring proclaiming (accurately) that he’d “shocked the world!”

* * *

For the first time, America was exposed to Ali’s nuclear-level charisma—his open-throttled enthusiasm and intellect that eventually (after far too long) wore down even the most traditionally entrenched brains. For one evening the boxing public got to revel in the story of a confident upstart, the fresh-faced Olympian who beat the badder (blacker) man. Clay was managed by a group of wealthy Kentucky businessmen, an old-boy network, and he was handsome and light-skinned. Without a Great White Hope, Cassius Clay was the next-best thing.

Clay was his birth name—a great boxing name, and the name he initially made famous. But unbeknownst to the general public, before the Liston bout, Clay became a member of the Nation of Islam. Young Cassius selected a new name—Cassius X, after Malcolm X—but that appellation was vetoed; instead, he was given the name we now know him by. And the very day after his big Liston victory, Cassius Clay announced that he was changing his name. He might as well have announced outright opposition to the Vietnam War! Which he soon did.

And just like that, public opinion flipped. The day before, Liston had been the baddie, but now everyone wished he’d won. A simple equation, it turned out: The one thing white America hated more than a black man with a criminal past was a cocky black man with radical politics.

A rematch was set—and then delayed because of backroom negotiations, venue problems, and an injury to Ali. Finally, a last-minute negotiation was reached: They would fight in St. Dominic’s Hall, in the tiny town of Lewiston, Maine, on May 25, 1965.

* * *

How anti-climactic that fight was—the fight featured in Leifer’s photo—after so much buildup.

Midway through the first round, Liston fell to the canvas, even though he seemed to have dodged Ali’s punch, and no witnesses on site could say they saw Ali connect. Nonetheless, with Liston suddenly and inexplicably down, referee Joe Walcott ordered Ali to retreat to a neutral corner. Ali refused; instead, he stood over his fallen opponent, gesturing and yelling, “Get up and fight, sucker!” Ali wanted a clean victory—and this smelled fishy—but no matter; before anyone knew what was going on, Walcott declared Ali the victor, and the fight was over.

“Get up and fight, sucker!” This was the “triumphant” moment that Leifer’s photo captured. So why did this image, instead of the others snapped of Ali, become the most iconic? “You have to understand, a lot of pictures aren’t appreciated when they’re first taken and then later they get a life of their own,” Leifer would say. “This photo became the way people wanted to see Ali, charismatic, tough, confident. The circumstances didn’t end up mattering.”

Of course, they did matter that day, May 25. The end of that fight remains one of the most controversial in boxing history. The blow that ended the match became known as “the phantom punch.” Even Ali was unsure as to whether or not he’d connected; footage from the event shows Ali, as he exits the arena, asking his entourage, “Did I hit him?”

Slow-motion replays seem to show that Ali did indeed connect with a quick, chopping right to Liston’s head (known later as the “Anchor Punch”) as Liston was moving toward him—but most agree that it wasn’t powerful enough to take down a big boxer like Sonny.

So did Liston take a dive? He was certainly mob-connected. Rumors persist to this day, though for every quote to support one theory, there’s a counterquote to support the opposite. Whole books have been devoted to various sides of the debate, written by authors who are either Tirelessly Researching Crusaders or Conspiracy Nuts, depending on which theory you support.

Financial investigations have shown that neither Liston nor his wife ever profited—outside of the original purse money—from the fight. Some claim that Liston already owed a bunch of money to the Mafia, and by taking a convenient dive, he simply paid off his debt. But if Liston was under the control of the mob, it’s hard to imagine they’d want Ali, a man they didn’t control, to be the champ—but again, who knows?

An equally popular theory is that Liston was frightened into taking a fall by the Nation of Islam. The group certainly was militant and broke into sometimes violent factions—Malcolm X had been assassinated just a few months before the fight. Liston supposedly told one biographer that this is why he went down, fear of assassination, but he gave other interviewers contradictory quotes. Again, who knows?

* * *

Leifer, for his part, seems to fall on the side of an Ali knockout, but he also confesses, “I can’t tell you that I saw the punch that put Liston down.” At the least, most seem to agree that Ali wasn’t facing the Liston of past years. One New York Times writer noted that Liston “looked awful” in prefight workouts, and it was reported that Liston’s handlers had been secretly paying his sparring partner $100 to take it easy on the big man. Liston’s handlers knew “he didn’t have it anymore,” according to another Times writer.

“The truth is,” Leifer said, “I haven’t seen the knockout punch in half the great fights I’ve covered. You’re thinking of strobe lights, batteries, and so many other things.” But even if he didn’t care much about that famous punch, Leifer cared a great deal about Ali. Indeed, though Leifer would go on to become one of the most noted sports photographers of his generation and a great photographer in general, Leifer always counted Ali as his favorite subject. The day of that phantom punch in Lewiston, Maine, was just the early phase of a relationship between photographer and subject that continues to this day. Leifer has photographed Ali in over 35 fights and at 20 photo shoots.

Leifer doesn’t shoot photographs anymore; he’s turned entirely to filmmaking—though there remains one subject for whom he’d shoot a still image. “I’d photograph Ali anytime.”

* * *

But however bright Ali’s ascendance, conspiracy theories on Liston’s fall still bred behind the scenes. The primary source, the only man who could really confirm or deny any of the theories about the phantom punch, was found dead in his Las Vegas home on Jan. 5, 1971.

An autopsy revealed that the cause of Liston’s death was a heroin overdose. The police determined that there were no signs of foul play. Still, some wonder.

Though heroin was discovered, no heroin paraphernalia was found inside the house, and also there’s this: Big Sonny had one lifelong fear—an almost cute phobia for a man so imposing, if it hadn’t been such a truly crippling terror, a fear that, even when he badly needed the money, caused him to cancel a tour in Africa simply because it would’ve required him to get vaccinations—a phobia that would make Liston, brutal Liston, flee a doctor’s examination room.

Sonny Liston had a lifelong fear of needles.

The Finale

There’s this poem titled “The Boxers’ Embrace” by Richard Katrovas, and part of the second stanza goes,

A man—a fool and so a man—

will likely suffer for his manhood

as a boxer suffers for his bread.

What is more beautiful, more true

to who we are (for what we are)

than fighters, spent, embracing all

that each had tried to murder from

the first bell to the last, and what

may offer greater hope for us,

for some of us, than that embrace?

That embrace always struck me as such a touching moment in the sport. It’s called a “clinch” and generally happens when a boxer needs rest or relief from the opponent’s blows, and the end of the round isn’t close enough to save him. The boxer wraps his arms around his opponent, hugging him, so punches can only land on his back.

But sometimes, at the end of a particularly long and brutal bout, it almost doesn’t matter who starts the clinch—once one boxer goes for it, they both seem to fall into it, sustain it, both need the respite; they lean on one another, and if either were to move away quickly, the other would fall; yet they don’t move away; for a very short time, they lean into each other like lovers at the end of a particularly slow dance. Seeing such a clinch, one wonders just how profoundly tired an athlete has to be to rest chest to chest, even for a moment, against the man he’s spent months preparing to brutalize.

So I wonder if, maybe, Sonny Liston was tired. Tired of being tired.

He might’ve taken a dive because of the Nation of Islam, he might’ve taken a dive because of the Mafia, or maybe there wasn’t a dive at all, just an unfortunate stumble and bumbling officials. But if Liston did take a dive, maybe it was an internal dive, taken at some unknown time days or months before the fight.

He was promised over a million dollars for his first fight with Clay, and yet, by the time Mafia paymasters cut his check, Liston made a laughable fraction of that. It’s a great tradition in boxing management—“fees” finally leveraged for previously “free” hotel stays, bar tabs, etc.—and for the Ali rematch, Sonny Liston was once again promised a million, never delivered. I wonder if, somewhere, he just said fuck it.

I don’t mean he walked into that ring in Lewiston thinking, I’m taking a dive. I mean something deeper down wanted to take a dive, even as his conscious self tried to fight for victory. Something like what F. Scott Fitzgerald writes of in The Crack-Up, when—curiously enough—he employs a pugilistic metaphor:

Of course all life is a process of breaking down, but the blows that do the dramatic side of the work—the big sudden blows that come, or seem to come, from outside—the ones you remember and blame things on and, in moments of weakness, tell your friends about, don’t show their effect all at once. There is another sort of blow that comes from within—that you don’t feel until it’s too late to do anything about it, until you realize with finality that in some regard you will never be as good a man again. The first sort of breakage seems to happen quick—the second kind happens almost without your knowing it but is realized suddenly indeed.

And in the Katrovas poem, he describes brutality as “the pain of father’s belt,” and Sonny knew that pain more than most. Certainly Sonny understood how “a boxer suffers for his bread.”

Nonetheless, for maybe a last time, he whipped himself into shape to face Ali late in 1964—and then Ali had a hernia, the match was put off for six months, and Sonny fell out of shape. Back at the casino, living that casino life, his body fell into disrepair—and then he was once again cheated out of over a million dollars. Some part of him might’ve given up, as Fitzgerald says, “without your knowing it” and was only “realized suddenly indeed” when he went down from a punch that could never have felled him physically if something incorporeal hadn’t already been cracked.

Isn’t this how most things break? After a romantic breakup, for example, one often wonders about the specific moments of the split, the night it happened—what could one have done differently to keep the fracturing at bay, that night, that morning, that afternoon on the phone? But later, of course, one sees it wasn’t about those moments at all—that the breakup was just the logical outcome of fissures that had already happened and happened slowly, undetected, much earlier, stacking one upon the other. The headline is never the real story—the real story is a slow, nearly imperceptible nurturing of resentments. Breakdowns, small ones, over time.

*Correction, May 26, 2015: This piece originally misstated that Neil Leifer’s work was buried in the back of Sports Illustrated. The photo received a full-page spread in the magazine but failed to make the cover. It also misstated that Leifer held the distinction of being one of only two photographers to shoot the fight in color. It also misstated that Leifer was bumped from his preferred side of the ring by Herb Scharfman; Scharfman merely got to pick first. It also misstated that Leifer’s editor espied the photo and submitted it to the “Pictures of the Year” contest. Leifer submitted the photo himself.

So maybe, just here, he should be seen as he wanted to be seen, like in this photo long before Ali, when he was first about to become the champ:

Photo by Bettman/Corbis

Sonny Liston is buried in Paradise Memorial Gardens in Las Vegas, and his headstone bears just a two-word epitaph: “A Man.”