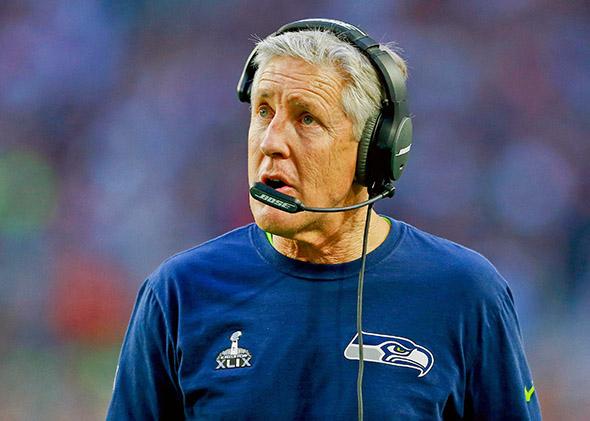

Pete Carroll’s decision to pass on Sunday on the most significant play in Super Bowl history was instantly questioned as one of the worst football decisions of all time. NBC’s commentating crew could not believe that Carroll opted to pass on second-and-1 with 26 seconds left in the game when he had one of the best rushers in the NFL on his side, while Hall of Fame runner Emmitt Smith flatly declared it to be the worst call in the history of the sport. With the benefit of hindsight knowledge of Malcolm Butler’s interception, it’s easy for pundits to make such declarations. But how bad of a call was it, really?

I can say without a doubt that Butler’s pick was the most critical play in any Super Bowl ever because of a concept called Win Probability, which directly measures the impact of a play on the outcome of a game. Simply put, it’s a model of how likely a team is to win the game at any point, given the score, time, down, distance, and field position. The difference between a team’s Win Probability at the snap and its Win Probability after a play is called Win Probability Added. In this case, Seattle had an 88 percent Win Probability on second-and-goal, and after the interception it plummeted to near zero, making the Win Probability Added negative 88 percent.

The next nearest contender is Buffalo kicker Scott Norwood’s missed field goal at the end of Super bowl XXV against the Giants, worth negative 67 percent Win Probability. “The Helmet Catch,” Giants receiver David Tyree’s miraculous helmet-aided reception in Super Bowl XLII, was worth 22 percent WPA, less than you might think because the Giants still had another down to try to convert if he hadn’t made the play. Patriots kicker Adam Vinatieri’s game-winning field goal against St. Louis in Super Bowl XXXVI was worth only 17 percent, because had he missed, the game would have remained tied at 17–17. Ty Law’s pick-six in that game was actually the biggest play, worth 26 percent Win Probability Added. Earlier games of the Super Bowl era had relatively few big plays, but Baltimore’s interception of a Dallas pass to set up a short game-winning field goal to win Super Bowl V was good for 28 percent WPA.

So the interception in Sunday night’s game was historically enormous, but what about the play call itself? The Seahawks are a great running team, so why risk an interception when running on the goal line is the safest bet? The issue was clock management. On second down with 26 seconds remaining and one timeout, the Seahawks would have had to pass on either second or third down to guarantee they would have time for a fourth down if needed. If Seattle would have to pass at least once, it would be better to do it on second rather than third down because it would force the Patriots to respect both options on all remaining downs. Had Seattle run on second down and failed, it would have had to use its final timeout. This would mean that New England would know a pass was very likely on third down. If that had happened, the Internet would now be bashing Carroll for an entirely different reason.

Carroll also explained after the game that the team didn’t have the matchup it wanted on the play to call a run. With a pass-friendly set of one running back, one tight end, and three wideouts in the game, the Seahawks expected New England to have smaller, quicker defenders in on their side to defend the pass. New England didn’t bite and kept its goal-line personnel in, so the Seahawks thought the matchup favored a pass. Interceptions are extremely unlikely from the 1—Russell Wilson’s was the first of the year—so the risk seemed worth it. Between the matchups and the clock considerations, the decision to pass seems defensible, but the play call of a quick inside slant and Wilson’s decision to pull the trigger remain subject to criticism.

But an interception wasn’t the only added risk of a passing play. There was also the possibility of a sack and higher probabilities of a penalty or turnover. There are any number of possible combinations of outcomes to consider on Seattle’s three remaining downs—too many to directly evaluate. So I ran the situation through a game simulation. The simulator plays out the remainder of the game thousands of times from a chosen point—in this case from the second down on. I ran the simulation twice, once forcing the Seahawks to run on second down and once forcing them to pass. I anticipated that the results would support my logic (and Carroll’s explanation) that running would be a bad idea. It turns out I was wrong. The simulation—which is different than Win Probability—gave Seattle an 85 percent chance of winning by running and a 77 percent chance by passing. It turns out the added risk of a sack, penalty, or turnover was not worth the other considerations of time and down.

The Seahawks put themselves in the situation where they felt they needed to pass because they wasted a timeout and then got a little too cute with the clock. It was certainly smart for them to burn some time so New England would not have time to respond if Seattle scored quickly, but they burned too much and ended up putting themselves in a box.

The only comparably bad coaching scenario in Super Bowl history might be Mike Holmgren’s decision to allow Terrell Davis to score the go-ahead touchdown in the final minutes of Super Bowl XXXII. Holmgren assumed the Broncos would at worst be able to break the tie with a field goal, and Holmgren’s intent was to give Packers quarterback Brett Favre enough time to lead a comeback drive. But his decision was premature. The Packers would have been better off forcing the field goal. After the game Holmgren admitted he was confused by a previous penalty and believed it was first rather than second down.

In terms of worst coaching moments ever, the “Red Right 88” play in the 1981 AFC championship game may serve as the best comparison. The Browns trailed the Raiders by 2 points in the final minute of the game with the ball on the Oakland 13. Instead of running or even taking a knee, Browns head coach Sam Rutigliano called for a pass, which was intercepted in the end zone, stealing the win for the Raiders. A field goal from that region of the field is about a 95 percent proposition in today’s game. Back then it was probably something closer to 85 or 90 percent. In that case, the play call itself might be held accountable for the entirety of the 90 percent or so Win Probability lost because taking a knee and then trying a field goal would have been virtually risk-free.

If we include regular-season games, the 1978 Miracle at the Meadowlands would certainly be up there for worst call of all time. With only a handful of seconds remaining and a 5-point lead over the Eagles, the Giants called for a run instead of a taking a knee. The thinking by the Giants was that they did not want to expose their quarterback to any possibility of injury and kneeling may have left at least one second on the clock, which would have required a play on fourth down. The handoff to former Dolphins star Larry Csonka was dropped, and Eagles defensive back and future NFL head coach Herm Edwards was able to scoop the ball and run for the winning touchdown. We don’t need win probability to tell us this was a 100 percent bad call.

To be fair to Carroll, you have to separate the effect of the play call and the outcome of the play on the field. Seattle’s call by itself didn’t cost them the game, the interception did. From the perspective of the decision-maker, the process is a little bit like a roulette wheel. Perhaps the wheel had a few more red slots than black, and the bettor erred by putting his chips on black. But as the wheel slowed, the ball fell on green.

Seattle’s decision was not the best one possible, but it was defensible and supported by some reasonable considerations. Ultimately, it was a great defensive play that truly decided the game.