Being a successful college basketball coach is a pretty nice racket these days. Make a deep run in the NCAA tournament—or, better yet, win a national championship—and suddenly you’re afforded an authority that extends well beyond the hardwood. You get to write books, give lucrative speeches, and star in American Express ads. More often than not, these star coaches have little to offer beyond X’s and O’s. Nonetheless, the most famous college basketball coaches today are no longer valued as mere instructors of the game. It’s not even that they’re admired for their leadership. They are treated as philosopher-kings.

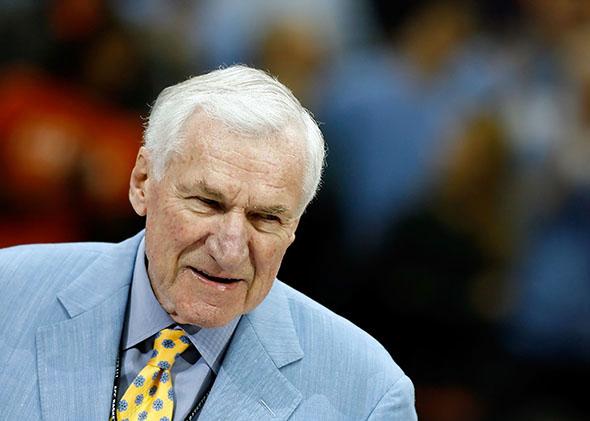

Dean Smith, who died over the weekend at the age of 83, was the rare college basketball coach who actually knew a thing or two about philosophers. The study in his home was filled with the works of Martin Buber and Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Paul Tillich and Robert McAfee Brown, and other writers recommended to him by his sister, who had gotten her master’s at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Late at night, after he had finished watching game film of his University of North Carolina team, Smith would pull a tome off the shelf and flip through the pages until he went to sleep. He credited the theological writer Catherine Marshall’s theory about “the power of helplessness”—which he came across one night early in his career, when the Heels were struggling to such a degree that the young coach had been hung in effigy on campus—for allowing him to radiate the inner calm that came to characterize his coaching demeanor. “It made me less anxious,” he later wrote. “Although I never talked to my team about my realizations, I do think they sensed something, a change in me. They seemed to relax too, and we started a streak of very good basketball.”

There was much beyond basketball that interested Smith—he liked to tell people that he read the editorial page before the sports page of the multiple newspapers he had delivered to his office—and his life was a testament to those interests. Although he is best known for the feats his teams accomplished on the court—two national championships, 11 Final Fours, and 879 wins at UNC, and an Olympic gold medal with the U.S. national team—his off-the-court achievements are what ultimately set him apart from his fellow members of the elite coaching fraternity.

There was perhaps no issue more important to Smith than civil rights. Most famously, in 1966, he recruited Charlie Scott to Chapel Hill, making Scott the first black scholarship athlete in the University of North Carolina’s history and the first black basketball star in the Atlantic Coast Conference. But Smith wasn’t like other pioneering coaches, who broke college sports’ color barrier for purely pragmatic reasons. (Alabama football coach Bear Bryant famously started recruiting black players to Tuscaloosa only after the University of Southern California—and its fullback Sam Cunningham—had run over the Crimson Tide in a 1970 contest.) To Smith, racial justice was about much more than winning and losing. “It was simply the correct thing to do,” he wrote. Smith understood this far sooner than many other white Americans.

As a teenager in Topeka, Kansas, he’d persuaded his high school principal—five years before the Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education—to integrate the school’s basketball team. Nine years later, as an assistant basketball coach at UNC, he took it upon himself to help integrate Chapel Hill when he and his pastor invited a black theology student with them to dinner at the town’s finest restaurant, which was then still segregated. Since the Tar Heels ate many team meals there, Smith was betting that the restaurant wouldn’t want to jeopardize that regular business by refusing to serve him and his guest. Still, back in 1958, it was a gamble. As Smith’s pastor later recalled for John Feinstein: “Back then, he wasn’t Dean Smith. He was an assistant coach. Nothing more.” Smith and his guests were served and a bastion of segregation reluctantly fell.

Even after Smith became a brand name—when many of his similarly accomplished colleagues began to shy away from doing or saying anything controversial for fear of damaging their own brands—he continued to act on his convictions. A staunch and unswerving liberal, Smith protested against the Vietnam War, campaigned in favor of a nuclear freeze, and supported gay rights. He was such an avowed opponent of capital punishment that he’d frequently take his teams to visit North Carolina’s death row at Central Prison in Raleigh and once told North Carolina’s governor, “You’re a murderer.”

Smith was similarly outspoken on behalf of his players: He was an early advocate for paying college athletes and he used to set aside a portion of his $300,000 annual salary from Nike—for putting the company’s sneakers on his players’ feet—to a fund that helped players who didn’t graduate pay for their degrees. (He also divided up half of that Nike paycheck between his assistant coaches and administrative staff.) Once, when Duke’s Cameron Crazies student section questioned the intelligence of UNC’s black star J.R. Reid with the sign “J.R. Can’t Read”—a sign that Smith and others considered racially motivated—Smith boasted to reporters that Reid and Scott Williams, another black UNC player, had higher combined SAT scores than two white Duke stars, Danny Ferry and Christian Laettner. All the while, Smith was a fervent booster of the university that employed him, frequently lamenting that it was a sign of society’s skewed values—“a Kierkegaardian ‘switching of price tags’ ”—that he received more praise and attention than UNC’s professors.

All of which is why Smith’s death—and the several years that preceded it, when the retired coach was suffering from dementia—is especially painful for some people here in North Carolina. It’s been a tough time of late for liberals in this state. Ever since Republicans won control of the Legislature in 2010, and the governor’s mansion two years later, North Carolina’s heretofore moderate politics have taken a dramatically rightward turn. The state’s pioneering Racial Justice Act, which allowed death row inmates to challenge their sentences on grounds of racial bias, was repealed; a new voter ID law, which shortens the early voting period and eliminates same-day voter registration, was enacted; and public education spending, the thing that once set North Carolina apart from so many of its Southern neighbors, was slashed.

It’s not as if Smith could have prevented these developments. But it’s safe to say that, unlike so many of his coaching brethren, Smith would have not only been aware of his state’s reactionary turn; he would have done everything in his power to address it. In his doing so, those beleaguered North Carolinians who shared his views could take comfort in knowing that a man who was revered by practically everyone in the state—conservative and liberal alike—was making their voices heard.

Perhaps more importantly, he would have taken vocal stances on matters he could successfully influence. While so many of today’s supposed coaching giants are too timid to address the issue of college sports reform—seeing as how they benefit most from the exploitation of college athletes—Smith, in word and in deed, would have kept up the pressure on the NCAA to make changes. In fact, the times have never been riper for a true philosopher-king coach—someone to lead, someone to speak out, someone to show the way forward. It’s a shame that the one man who actually fit that description is no longer stalking our sidelines.