My childhood bedroom is in transition. Dunes of dry paper have risen around the periphery, trophies sag under veils of dust, certificates curl at the corners. On the floor are piles of old clothes: my parents’ emptied closets, drifting towards the Goodwill store on Route 17. It’s a room that no one lives in, and feels like it. In this room, by a closet door, is a box marked Do Not Open Until 2010.

There is a box like this in many bedrooms and attics and garages, and also in just about everything written about baseball cards in the last 10 years. The only reason the contents of my Do Not Open Until 2010 box and your Do Not Open Until 2010 box are not still depreciating in value is that further depreciation would be impossible. When I wrote those words on that box, I saw the cardboard inside as a retirement fund. Today, it is 20-odd pounds of bookmarks.

This is where the story of the baseball card industry’s collapse usually ends, but it is not quite an ending. For one thing, the industry still exists, albeit after a decades-long right-sizing process. For another, there’s the matter of the animating passion that filled all those boxes with baseball cards in the first place. And this is how I came to open a pack of baseball cards on my phone while waiting for Chinese takeout.

***

“The initial thought exercise, in 2012, was, If you were to re-create a baseball card, in our day and age, what would it look like?” Michael Bramlage told me. “First thing was, it should live on your phone. You know, the phone in your pocket is about the same size as a baseball card.”

Bramlage, the vice president, digital at the trading card giant Topps, is talking about Bunt, the free app I used to open a pack of Topps Frozen Phenoms while waiting for my dumplings. My phone shuddered, and gold digital confetti exploded on screen when the pack turned out to contain a “super rare” Yasiel Puig card.

A great many quotation marks are in order here. The “pack” I opened existed only on my phone; the closest I will get to feeling that Puig “card” in my hands came in that moment when my phone shook with delight. Were I to trade that Puig card to another Bunt user—Bramlage says trade offers pour in at the rate of more than one per second—any return I’d receive would be similarly notional. If I kept it, I could slot it into my Bunt lineup, and Puig’s real-world statistical output would earn me points in an in-app fantasy game, which would in turn earn me “coins” that I could use to buy more digital cards.

You can also spend real money to buy those coins—it costs $9.99 for 20,000 or $74.99 for 500,000 if you’re in the mood to splurge. (In the interest of disclosure, when I reached out to Topps for this story, they deposited 100,000 coins into my Bunt account.) You can use those coins to buy various types of packs, including Frozen Phenoms, which—for reasons that are not entirely clear—feature players like Puig, Mike Trout, and Clayton Kershaw surrounded by snowflakes.

If any or all of this is mind-bending to you, you are probably not Bunt’s target audience. Eighty-one percent of Bunt users are between the ages of 13 and 25, and as such find nothing terribly weird about a baseball card that doesn’t exist in any corporeal sense. But as a comparatively doddering 36-year-old, I felt both old and weirdly, preemptively tired—like, octogenarian-on–Yik Yak tired—in my engagement with Bunt. Bramlage is right that the younger demographic is “very rational” in its preference for phone-bound virtuality over fragile cardboard—a photo on Instagram is indeed more reliably backed-up and more readily shared than one in a scrapbook—but I’ve never known baseball cards as anything but baseball cards. Having traded them with classmates on a literal gravel-and-hormone schoolyard did little to prepare me for the scaled-up proposition of trading them on a sprawling virtual bazaar.

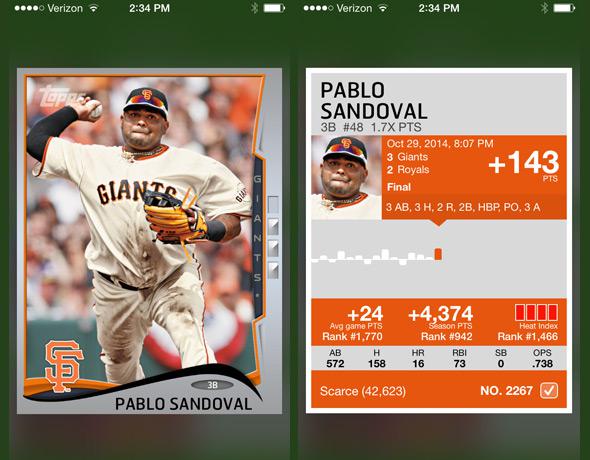

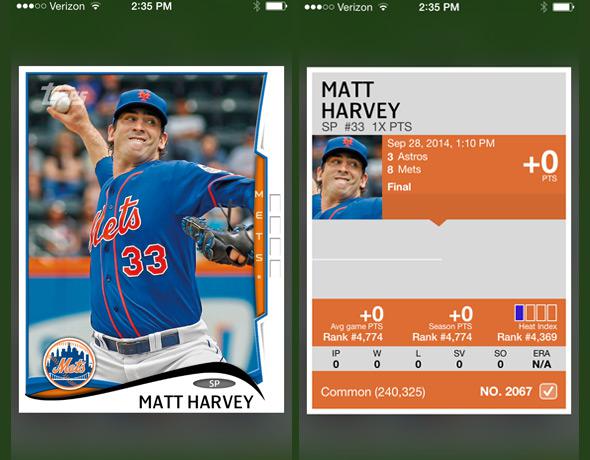

Bunt screenshot (The Topps Company, Inc.)

For Topps, that virtual bazaar is the future of the card business. The company launched a rudimentary iPad version of Bunt in 2012, and has been updating the product every four weeks since. The result is a Web success big enough to leave a Pablo Sandoval–sized offline footprint, both through a robust secondary market—rare Bunt cards, and others with “digital signatures” that mirror players’ autographs, are priced in the hundreds of dollars on eBay—and multimillion dollar revenues through the app.

Whatever its ontological challenges, Bunt has answered a question that the baseball card business would not have even known how to ask when I worked as an editor at Topps, nearly a decade ago, back when the teetering empire still stood on a foundation of cardboard. It would have seemed like a rhetorical question, then: How much money could be made through selling baseball cards that did not need to be printed, packed out, or shipped? What if the cards just were, and they were somehow there for the buying, even as you stood there in the neon nowhere of a Chinese restaurant, waiting on an unhealthy lunch?

***

During a brief but violent boomlet in the late 1980s and early 1990s, baseball cards were touted as not just collectibles but an alternative investment strategy. The industry responded by printing tons of cards: 81 billion per year by the early 1990s, which looks like a joke but is in fact a widely accepted estimate. People my age responded by buying a ton of cards and keeping them. Without scarcity, the cards would have no real value. The industry’s self-thwarting tsunami of supply did not so much exceed demand as extinguish it.

Comparisons between collecting and the stock market, which were common at the time, were ridiculous in every way except for the implied speculative frenzy. Starting in 2001, Topps went so far as to create a virtual stock market for virtual cards—introduced via initial public offerings with limited runs and traded on a secondary market—which it called eTopps. Logistical problems on the printing side and a buggy, flub-prone website—it’s still up, but has been in zombified stasis since 2012—ultimately undid that online venture. While eTopps was not a bad idea, it was a fundamentally sour one that was, as former Topps marketing director Daniel Manco said back in 2001, “about building the value of your portfolio and sharing with people that you know more than them.” Even the television ads for eTopps had a grim Office Space–y vibe and an unforgivably brown visual approach.

If Bunt can continue to succeed where eTopps didn’t, it will owe as much to a recalibration in philosophy as to a quantum leap in technology. Where eTopps followed the new, grown-up money in collecting to its logical/ridiculous conclusion, Bunt aims to reconnect with the hobby’s roots, swapping the grandiose affectations of macroscale capital for old-fashioned schoolyard arbitrage. That idea of collecting, in which cards were for kids to buy, flip, and trade, was at the heart of the empire built by the recently deceased Sy Berger, Topps’ resident mastermind and household saint. “We’re trying to recreate, digitally, that collecting ecosystem,” Bramlage says.

This is a concise, if rather airless, way of articulating what the industry stopped saying long ago: That baseball cards must at some basic level be fun, and should be treasured and traded with equal vigor, and that they are most fully and delightfully real when understood in that way. It is also an acknowledgment of something that Major League Baseball—for which Topps is the official purveyor of cards both cardboard and digital—has been stubborn about admitting, which is that the game will curdle if it stops being a thing that young people dream about.

It is a strange and somewhat unsettling thing to see all the accrued treasure of my childhood shrunk mercilessly to the size of an app. But progress makes Grandpa Simpsons of us all, and this is not a cloud worth screaming at. It’s tough to see Bunt as anything but a necessary evolution in a business that needed one, and a way to make something I cared about relevant and appealing to people who’ve never had reason to think of it as either. That’s not a bad thing. Chris Olds, the editor of Beckett Sports Card Monthly and an active Bunt user, says the app will likely be additive, driving interest in actual cardboard cards. “I think it’s there to perhaps spark interest in the main product, but I don’t think it will replace it,” he says.

Bramlage echoed that point, saying that Topps research has shown “we’ve become the on-ramp for physical collecting” for some young users. But Bunt also works as a thing apart from the old and shrinking cardboard economy. It’s not any more difficult to imagine the former surpassing the latter—or boxing paper cards into a progressively cozier niche—than it is to imagine the New York Times arriving on more iPhones than doorsteps. You and I might prefer one over the other. But if there is not someone in line behind you, your favorite store is going out of business.

There is a certain leap of faith required when it comes to understanding oneself as the owner of thousands of baseball cards that 1) exist on your phone and 2) do not exist anywhere else. “We really believe that we are selling an experience around a digital object that should persist as long as physical cards have,” Bramlage says. “We believe that these are real physical objects that happen to be available in a digital format.”

This is perhaps more metaphysics than a virtual Bartolo Colon baseball card can bear. But, to some extent, this willful alchemy has always been what made card collecting work. After all, baseball cards only exist as an investment because we—kids and adults, all of us held in that tenuous balance between the two that fandom demands—choose to invest these cardboard rectangles with value in the first place. These cards are worth what we decide they’re worth and only that much, and that has always been true. One generation’s cards are neglected in dust-shrouded boxes; another’s move and grow, relentlessly, in the permanent mint condition of the Internet. Which seems more valuable to you?