Before any of the six entrants in the 2014 Sinquefield Cup had nudged a white pawn to e4, they’d already been hailed as the strongest collection of chess talent ever assembled. The tournament, held in St. Louis, featured the top three players in the game. The weakest competitor in the field was the ninth best chess player on the planet.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Gwladys Fouche/Reuters.

The favorite was current world No. 1 and reigning world champion Magnus Carlsen. The young Norwegian—who is among the best players in the history of chess—strolled into the lounge of the St. Louis Chess Club as the most alluring grandmaster ever, a brilliant, handsome 23-year-old with a modeling contract for the clothing company G-Star Raw. Forget about his overmatched foes. If anything could stop Carlsen, his fans reckoned, it would be the swirl of distractions occupying the parts of his brain not given over to memorizing Nimzo-Indian variations.

As the tournament began on Aug. 27, Carlsen was mired in an ongoing faceoff with FIDE, the international governing body of chess. There are a few things you should probably know about FIDE—or the Federation Internationale des Echecs, if you’re feeling continental. FIDE is, by all accounts, comically corrupt, in the vein of other fishy global sporting bodies like FIFA and the IOC. Its Russian president, Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, who has hunkered in office for nearly two decades now, was once abducted by a group of space aliens dressed in yellow costumes who transported him to a faraway star. Though I am relying here on Ilyumzhinov’s personal attestations, I have no reason to doubt him, as this is something about which he has spoken quite extensively. He is of the firm belief that chess was invented by extraterrestrials, and further “insists that there is ‘some kind of code’ in chess, evidence for which he finds in the fact that there are 64 squares on the chessboard and 64 codons in human DNA.”

One of the many conspiracy theories bandied about in the fever swamps of the chess world’s collective imagination has it that Ilyumzhinov (and his friend Vladimir Putin) yearn for a return to the glory of Soviet-era chess supremacy. Such a shift in the chess world order would require a demotion of this impudent Norwegian tyke and the promotion of a proper Russian world champ. Another theory holds that Ilyumzhinov resents Carlsen for having supported Garry Kasparov when Kasparov launched a (doomed) campaign to unseat Ilyumzhinov as FIDE president. Whatever the underlying issues, the upshot is that Carlsen and the governing body have been squabbling over the Scandinavian’s upcoming FIDE title defense.

The title belt in chess, as in boxing, may be claimed only by defeating the reigning champ in an officially sanctioned, one-on-one matchup. Through a series of qualifying events, FIDE had chosen a challenger for Carlsen—the current world No. 5 Viswanathan Anand of India, who was not in St. Louis, and who lost to Carlsen in last year’s title match. FIDE hoped to host this year’s event in November in the abandoned Olympic facilities of Sochi on Russia’s Black Sea coast.

Carlsen seemed reluctant to sign on. Rumors swirled in St. Louis that if he didn’t cave soon, his title might be stripped from him. Some whispered that he’d already chosen to forfeit, unwilling to accede to the conditions proffered by FIDE and its alien-obsessed president. FIDE insisted it could accept Carlsen’s final word on the matter no later than Sunday, Sept. 7—one day after the last round of the Sinquefield Cup.

In St. Louis, all of this seemed to be weighing heavily on Carlsen’s enormous brain. I was invited to cover the tournament with the enticement that I’d be granted a generous chunk of time with the world champion. When I arrived, however, he refused to speak to me, even though doing so violated his contractual appearance obligations. His manager apologized, explaining in an email, “From time to time we need to block out all kind of media activities.”

Even without the distraction of talking to me, Carlsen was not playing to his typical high standards. Meanwhile, one of his rivals was in the midst of a streak so extraordinary it threatened to overshadow anything Carlsen had ever done. All of which, in confluence, transformed the Sinquefield Cup into one of the most emotional, dramatic, newsworthy chess events of the past 40 years. At most 300 people were in St. Louis to see it.

* * *

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Lennart Ootes.

Rex Sinquefield was born with a cleft palate. By the time he was 7, he’d lost his father and been left in the care of a St. Louis orphanage. Despite these humble beginnings, he went on to earn an MBA from the University of Chicago and, in 1973, to invent what many believe (and he insists) was the first passively managed, market-weighted S&P 500 index fund.

When Sinquefield retired, his bank account bulging, he returned to St. Louis—this time in possession of considerably more wealth and influence. He joined the boards of various charities and cultural institutions, and backed conservative economic causes. (Sinquefield is not a big fan of taxes or teachers unions.) In his spare time he attempted to rescue American chess.

Sinquefield launched the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis in 2008 on a quaint, brick-laden block in the city’s Central West End neighborhood. The center has 6,000 square feet of playing halls, libraries, and classrooms, and more than 1,000 dues-paying members. Across the street—past a phalanx of outdoor chess tables arranged on the sidewalk—sits the World Chess Hall of Fame. Sinquefield apparently dug its archives out of mothballs from some sad venue in Florida, augmented the existing collection with his own trove of chess memorabilia, and housed it all in a gorgeous, dedicated facility replete with a gift shop full of Bobby Fischer tchotchkes. Not far from here, on the same side of the city, is Webster University, home to the nation’s best college chess team.

Photo by Dilip Vishwanat/Getty Images

Together, these institutions have made St. Louis the new center of American chess. Susan Polgar, among the best female chess players ever, relocated here to coach the Webster team. Hikaru Nakamura, the current U.S. No. 1, and No. 7 in the global rankings, moved from Seattle to join the scene. And now the Sinquefield Cup has become the premier North American chess event, this year attracting one of the strongest tournament fields in the game’s modern history.

Sinquefield has built a small, self-contained, chess-loving universe here. Lester’s, the bar next door to the club, has given over a few of its TVs to broadcast chess instead of Cardinals games. A pair of live commentators in the corner of the tavern explicate 15-move opening sequences as a handful of chess fans chow down on chicken wings. Across the street at the Hall of Fame, a second set of experts holds court in a more sedate setting, answering complex questions after each tricky move. Inside the Chess Club, people have purchased tickets that allow them to stand in the hushed parlor where the games are played—though complete silence is required here, and patrons are reminded never to address the players or to shout out a suggestion for a clever pawn sacrifice. The fans are mostly (though not all) men, and are invariably shod in the comfortable, black walking sneakers that are favored among a certain sort of older person. If you wandered in here by mistake, you might think you’d stumbled across a pretty decent normcore convention. Albeit a modest, regional one.

Beyond the velvet rope that cordons off three wooden chessboards and three accompanying pairs of facing armchairs, the players cut far more stylish figures. Gone are the chain-smoking Russians who dominated the chess scene of yore. Modern players work out, staying in shape to boost their energy levels and mental stamina for long matches.

Photo by Lennart Ootes

Levon Aronian, the world No. 2, is a trim, 31-year-old Armenian in tailored clothes. Sadly, his distinctive eyewear will turn out to be more remarkable than anything he accomplishes in this tournament. Maxime Vachier-Lagrave—colloquially known, like many a Frenchman, by his three-letter monogram—is the weakest here by ranking, though, at 23 years old, MVL still has time to level up. Veselin Topalov, 38, is a former FIDE champ, but he now clings to world No. 6. The balding Bulgarian, narrow in face and lapel, is the eldest here by far and is already contemplating his inevitable fade from the top 10. He’s grown tired of the travel and the time spent away from his family. He doesn’t have the same thirst to study the game anymore, to keep up with new trends. “I don’t know what I’ll do,” he told me in a quiet moment when I asked him about his retirement plans. “I’m not going to show little kids how to move the pieces around. I’ll have to think about it.”

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Anna Solvova/isifa/Getty Images.

The lone American entrant is Nakamura, a 26-year-old who often chugs Red Bull at the chessboard. Though he is ranked seventh in the world, he seems to consider himself Magnus Carlsen’s chief rival, as evidenced by this November 2013 tweet in which he equates Carlsen with a mythological necromancer.

It’s a bold pronouncement coming from a man with a record of 0–11 (plus 15 draws) against the champ. Carlsen, for his part, seems less than threatened. In an interview with a Norwegian media outlet, he once referred to Nakamura as—I believe this was correctly translated—“inept.”

By the midpoint of the tournament, Nakamura has dug a prodigious hole for himself, with two losses, three draws, and zero wins. He’s prone to vivid facial expressions, and when he realizes he’s made an error he will bite his lip, shake his head, and stare vacantly at the board. After an especially egregious cascade of mistakes during a match against Aronian, the commentators on the online live stream described Nakamura’s position as “a terrible mess” and “simply bad.” Broadcaster Jen Shahade (a chess and poker player of some fame, and the author of the memoir Chess Bitch) asked, in what seemed to be genuine disbelief, “This is too weak to be something that he’d prepared in advance, right?” Meanwhile, on the screen behind her, Nakamura could be seen engaging in an amazing sequence of reactions as his fate dawned upon him: puffing out his cheeks; raising his eyebrows and exhaling sharply; turning away from the board in disgust; glancing back in a last-ditch glimmer of hope that, wait, hey, maybe I’ve spotted a miracle move but no, never mind, no of course I haven’t; and finally burying his face in his hands in a display of utter capitulation.

It may have been a teensy comfort to Nakamura to know that even the mighty Carlsen had managed just a single win in his first five games. Everyone in St. Louis agreed that the world championship negotiations were nibbling at the Norwegian’s mind. He wasn’t playing crisply.

Professional chess requires a level of peak mental alertness that most of us achieve only in the throes of searing tooth pain. And that level of heightened concentration must be sustained over the course of a four- or five-hour game. A grandmaster needs to execute 50 or 60 consecutive moves without making a single damaging error. He must recall appropriate countermeasures for dozens of possible gambits and subtle iterations of those gambits, all under the pressure of a ticking, pitiless clock. (Time limits in chess are confusing, but typically the players have 90 minutes total to make their first 40 moves. Beyond that point, it gets more complicated.)

Carlsen is known for vise-like gameplay in which he constricts the life from his opponents, slowly turning a minor positional advantage into a major one with an endless series of patient, precise moves. Whether it’s the distraction of regular bargaining sessions with a man who believes that chess was invented by space aliens, or something else, Carlsen wasn’t himself here.

Carlsen is the only active chess player in the world whom someone other than chess geeks might recognize. That’s partly due to his accolades (grandmaster at 13; simultaneous world champion of standard chess, rapid chess, and blitz chess; highest-rated player of all motherfreaking time) and partly due to some external factors (a Western not Soviet upbringing; his excellent spoken English; his Viking bone structure, fjord-colored eyes, and hay bale of hair). Carlsen is followed everywhere he goes by a small Norwegian news team captained by a beautiful blonde woman who interviews the champ on camera after every one of his matches. He’s arguably the biggest international celebrity in a 10-mile radius. Maybe 20.

Yet, by day five of the Sinquefield Cup, Carlsen was an afterthought. Something bigger was happening.

* * *

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Lennart Ootes.

Fabiano Caruana learned to play chess at a synagogue in Park Slope, Brooklyn. At 14, he became the youngest U.S.–born grandmaster. By that point, he’d already relocated to Italy, holing up closer to Europe’s top-level coaches and tournaments. Now 22 years old—he’s nearly two years younger than Carlsen—Caruana has been steadily climbing the FIDE rankings, and entered the Sinquefield Cup as the No. 3 player in the world.

Caruana started the tournament with a win, then another. Then another. And another. And another. At the halfway mark, when each player had faced all five of his opponents exactly once, Caruana was 5–0–0. Carlsen, meanwhile, was tied with Topalov in a distant second place, recording one win, one loss, and three draws. Players get no points for a loss, a half-point for a draw, and one point for a win. Given Caruana’s 2.5-point lead, many observers believed the tournament was essentially over.

To you and me, going unbeaten and undrawn in five straight tournament games sounds impressive. But to chess aficionados, Caruana’s performance is nigh on miraculous. It’s frightfully difficult to straight-up stomp another top-10 international grandmaster. If he’s determined to, and particularly if he’s playing with the white pieces (white goes first, and thus bestows an advantage by allowing you to dictate early play), a super-elite player can choose a cautious approach and quite reasonably expect to engineer a draw. Yet Caruana wasn’t merely avoiding draws and losses. In the words of one commentator, he was “spanking” his opponents.

There were, to be sure, elements of good fortune involved. When Caruana faced Maxime Vachier-Lagrave, with MVL playing black, the Frenchman unveiled a surprise opening sequence that backfired spectacularly. MVL is widely known to play the Sicilian Defense, which meant that after Caruana began the game by moving the pawn in front of his king two spaces forward (that’s pawn to e4, one of the standard first moves in modern play), everyone presumed that MVL would move the black pawn sitting in front of his queenside bishop two spaces forward in response (pawn to c5). On this day, atypically, MVL eschewed the Sicilian and moved that same pawn only one square forward—pawn to c6—a technique known as the Caro-Kann defense. Amazingly, that one square changes everything. Caruana hadn’t anticipated it. He had, though, studied this same opening during his preparation for a different match, against a different foe, four months prior.

“It was an unfortunate choice that my opponent made,” Caruana told me. “I’d looked at that same line some months ago. I’d prepared it for a different player and it just caught the wrong guy.”

Many of us have difficulty remembering shopping lists with four items on them. Caruana retrieved, from study sessions many moons and moves ago, a specific sequence of about 17 decisions necessary to defeat MVL’s sortie. As the Frenchman continued to play out the Caro-Kann sequence, Caruana executed his countermoves without a flub, making nuanced modifications in response to MVL’s own subtle variations.

Top-level grandmasters, of course, pull off this sort of thing routinely. But Caruana is earning a reputation as the most prepared player of his era—a man who studies everything and forgets nothing.

When I asked him about his hobbies outside of chess, he smiled and allowed that he basically has none. He watches movies to relax (he particularly enjoyed the Indonesian martial arts films The Raid and The Raid 2) and sometimes reads (he mentioned his fondness for The Iliad and David Sedaris). But mostly, he stares at chess games.

Photo by Lennart Ootes

“Hundreds of games are played each day all around the world,” he noted, in a voice that is oddly deep and authoritative given his slight frame and wispy moustache. “And a lot of them are important. They’re all available online, but you have to put in the time to look at them all. And you need to analyze, find new trends, keep trying to find new ideas to use against specific opponents.”

On the third day of the tournament, Caruana beat Carlsen using the black pieces. It was his third straight win, and the moment when the chess world began to focus on St. Louis with even greater interest. This, again, was a win birthed in preparation. “At some point he sacrificed a piece,” says Caruana of Carlsen. “It was an interesting sacrifice, even if it may not have been totally correct. But it turned the game into a very complicated one, almost immediately. And it turns out that I was better prepared for the complications. I outplayed him, and at the end he made a terrible move. He blundered. Although at that point it was probably already a win for me. But still, he could have put up a lot more resistance than he did.” (You can view the game, and more detailed analysis, on the website The Week in Chess.)

If there’s a rap on Carlsen, it’s that he’s the anti-Caruana: He doesn’t prepare as diligently as he could. With his openings, he seems content to let the game wander where it will, feeling secure enough in his ability that he believes he can mold any position into a victory. “It’s as though he serves underhand to just get the point started,” says analyst and grandmaster Ian Rogers, “because he knows he can beat you in the rally. But Caruana has the booming serve.”

When asked to describe Carlsen’s play, Caruana raved about the Norwegian’s tenacity. “When he has an advantage he almost never lets it go. Where other players are maybe ready to accept a draw and go home, he’s ready to work the extra two, three hours and convert his advantage, even if it’s a really tiny one.” Caruana also confessed that he tries to “avoid” certain types of games against Carlsen. “In some positions you can’t compete with him. Certain pawn structures he just plays like a machine. There are certain openings where I say, ‘I just can’t do that.’ But OK, certain positions he’s not as comfortable with. Just like any player, he can also play unconfidently.”

Caruana oozed confidence when he sat down with me on the rest day at the tournament’s halfway mark. You’d be confident, too, if you’d just destroyed the world’s best competition in a contest measuring the highest intellectual capabilities of humankind. Caruana is, on the whole, very respectful of his opponents, but his matter-of-fact tone suggested some deeply internalized assumptions about his own awesomeness. On Topalov: “I think that he’s not at his peak any more, his chess strength has declined a bit.” On the match with Carlsen: “It went very well for me from the start. … I outplayed him.”

Confidence can have interesting effects in high-level chess. When your opponent plays very quickly, it not only adds an element of time pressure (your clock begins to run the moment he finishes moving) but can also intimidate you into believing that he’s supremely well prepared for the approach you’ve taken. Which in turn might convince you to zag away from your planned course out of fear that you’re walking into a trap (which you may well be). In St. Louis, Caruana perched over the board with visible self-assurance, keeping up a terrifying pace of play. In part it’s because he really was prepared for everything his foes threw at him. But the effect snowballed. He got in their heads.

By the time Caruana won his fifth straight game to open the tournament, destroying Nakamura while playing with black, the commentators were struggling to situate this performance in historical context. Some brought up Anatoly Karpov’s run at Linares in 1994, when he won his first six tournament games (including one against a then-babyfaced Topalov) before Garry Kasparov at last slowed him down with a draw. There was also a magical Viktor Korchnoi showing in the 1968 tournament in Wijk aan Zee, Netherlands. But many think the field in St. Louis is stronger than those Karpov and Korchnoi faced. And Caruana was still going. Were he to win all 10 games without a blemish, it would likely be considered the greatest feat in the annals of tournament chess, stretching back to the 1800s.

I asked some experts to explain, to a layman, what sort of accomplishment it would be to go on a 10–0 run here. When not reaching for analogies from other sports—one grandmaster, in complete earnestness, likened it to pitching 100 straight innings of no-hit baseball—they invariably turned to Bobby Fischer. Fischer’s streak of 20 consecutive victories against grandmasters. Fischer’s mindblowing tournament performances. Fischer’s near-hallucinatory leaps of chess logic. Stumped for further superlatives with which to describe Caruana’s excellence, one chess expert resorted to the highest possible praise: Caruana, he said, was “Fischer-esque.”

* * *

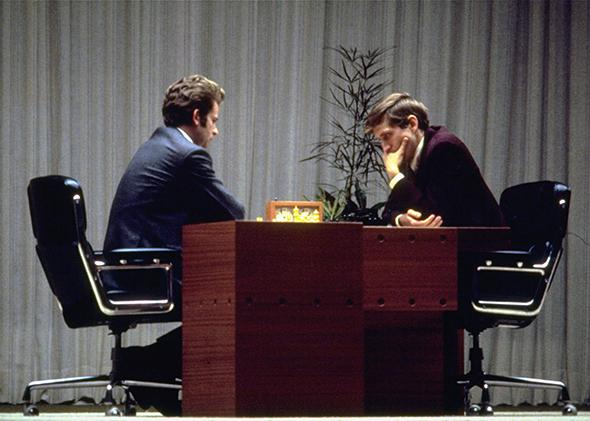

The 1972 FIDE title match in Reykjavik, Iceland, pitted Fischer, the American challenger, against Russian champion Boris Spassky. A series of Soviets had held the FIDE crown since 1948. There had not yet been an American-born champion.

Fischer was an eccentric, livewire personality. He lost the first game to Spassky, and then forfeited the second without even moving a piece—citing annoyance with the television cameras. Experts left him for dead. They figured he simply wasn’t up to the moment.

Photo by J.W. Green/AP Images

In the third game, with his 11th move, Fischer played Nh5—meaning he moved his centrally positioned black knight to the edge of the board. This went against a lot of standard chess wisdom. For one thing, knights are generally more powerful when they can lash out in myriad directions from a middle square. Even beginners know the rule of thumb: “a knight on the rim is dim.” But more puzzlingly, the choice allowed Spassky to destroy Fischer’s kingside pawn formation. The result looked to be awful, perhaps close to fatal, in the long run. But it had positional advantages that weren’t obvious at first glance. Spassky slowly grew flummoxed, and resigned. It was the first time Fischer had ever beaten him. The tide turned and Fischer went on to take the championship.

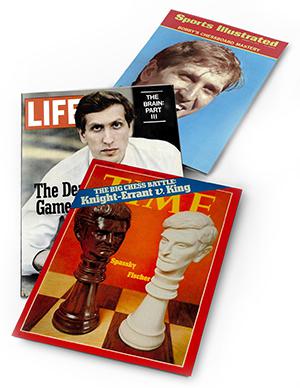

His victory was akin to the U.S. Olympic hockey team’s subsequent upset of the USSR in the 1980 Winter Olympics—both in its shock value, and in the fact that its cultural importance cannot be understood by anyone who grew up after the Cold War. The surrounding hoopla birthed a whole generation of American chess nerds. The gift shop in the World Chess Hall of Fame sells T-shirts that say, simply, “Nh5,” with those three characters superimposed over a silhouetted map of Iceland.

The chess craze that followed in the wake of that 1972 world championship match is now referred to as “the Fischer boom.” It was without doubt the peak moment for the game in America. Fischer appeared on the covers of Sports Illustrated, Life, and Time (the latter of which featured the American hero in the guise of a chess piece). Kids in Ohio bought My 60 Memorable Games and learned how to fianchetto.

Those days are long gone. Six years after Fischer’s death—his greatness sullied by a late-life torrent of anti-Semitic, anti-American rambling—chess remains a useful cultural referent, our go-to metaphor for strategic thinking. (A recent cover of the Economist showed Vladimir Putin walking amid giant, toppled chess pieces. The accompanying story was not about chess.) Movie set designers will forever place chessboards in the lairs of villains and on the bunk beds of child prodigies. But the game itself has dwindled in popularity. Chances are you didn’t tune in to the live stream of last year’s title fight between Carlsen and Anand. Chances are your 12-year-old nephew hasn’t begged you for a copy of Aron Nimzowitsch’s My System.

If there’s been any recent hope for a chess resurgence, it’s rested entirely on Carlsen’s broad shoulders. Young, good-looking, non-Russian, and blessed with genuinely transcendent skill, he’s the most marketable player to arrive on the chess scene this century. While at the table, he wears jackets and shirts emblazoned with the logos of his sponsors, like he’s a NASCAR driver: Nordic Semiconductor on his shoulder, Simonsen Vogt Wiig, a large Norwegian law firm, on his breast.

Photo illustration by Slate.

There will always be a core of diehard chess fans, but, Magnus or no Magnus, the wider interest isn’t there right now. The Sinquefield Cup—maybe the strongest chess tournament ever—drew fewer ticket buyers than an indie rock show. On a Tuesday when I was there, there seemed to be no more than 100 people in attendance. I was the only mainstream, non-chess journalist covering the event, save for the aforementioned Norwegians. The online broadcast drew about 75,000 worldwide viewers per day, which sounds respectable. Until you learn that the stream of a “League of Legends” videogame championship attracted an audience of 32 million. Televised poker, another “mindsport,” is all over cable TV and has launched a galaxy of star players. Chess has had no comparable successes.

Is the product the problem? Like poker, chess doesn’t offer up electric visuals. It is a still life of men seated at a table, hands pressed to the sides of their heads. But while poker is, at heart, a simple game, easy enough to grok that you can strategize along with Phil Ivey when he plays on TV, a grandmaster-level chess match is totally bewildering. The live stream commentators attempt to explain the thinking behind each move, and after a while you glean a basic understanding of what makes a position strong or weak, the value of developing your bishop here instead of there, and why a particular pawn is so vital to protect. But most of us will never manage even a rudimentary comprehension of the cogitations going on in these analytical geniuses’ brains. I might beat Ivey in a hand or two of poker, but the only way I’d beat a grandmaster in a game of chess is if I managed to swipe his pieces off the board when he wasn’t looking.

The rise of the computer chess engine may also have dimmed the game’s appeal. Just as my brain is hopelessly puny next to Magnus Carlsen’s, so is Carlsen’s compared to that of a modern chess-playing machine. In the last two decades—starting with Kasparov’s loss to IBM’s Deep Blue in 1997—it’s become clear that even the greatest chess minds are helpless against a hard drive. A computer can play a move that appears wholly nonsensical, only to watch it pay off later in a manner that the human brain couldn’t possibly foresee. Computers never tire or lose focus, never let emotion cloud their decisions, never get intimidated by their opponents’ quick, confident play. In a recent demonstration, Hikaru Nakamura failed to beat a powerful chess engine, even when he was allowed to consult a slightly less powerful chess engine. Ian Rogers spoke to me with reverent awe about watching a linked group of mainframes trade elegant moves in a way that an angel might play chess, if we could sit an angel in front of a chessboard. His recollection was that these computers had been retired soon after and were put to work running Dubai’s metro system or something.

Photo by Stan Honda/AFP/Getty Images

Maybe it takes a little shine off the game, knowing the strongest possible contest would pit two CPUs against each other. Yet we still enjoy watching Usain Bolt run, even though he can’t outsprint one of Google’s driverless cars. There is still a certain drama inherent in watching two people scale the heights of human potential, in competition with each other, battling nerves and fatigue. Though it is all a bit more exciting when those two people are representing the USA and the USSR in 1972.

Though computers make the players’ abilities seem worse by comparison, they’ve actually made them much stronger in absolute terms. A grandmaster can now check his instincts against the more empirical analysis of the engines. Some of the eccentric moves that worked for chess stars in the past wouldn’t fly against the honed, icy cold calculations of a Carlsen or a Caruana. And, reassuringly, the computers don’t know everything. They haven’t yet “solved” chess—meaning they don’t have an objectively perfect move figured out for every possible scenario. The game’s too complicated, even for them. As Caruana said to me, quite poetically I thought, “There’s always been a higher chess truth, which is pretty much impossible to grasp. Because there are too many moves. There are too many possibilities.”

The goat rodeo that is FIDE, with its corruption and its hidebound ways, does the game no favors. It makes little sense for Carlsen to have a world championship rematch against the world’s fifth-ranked player, as would be the case if the Norwegian acceded to FIDE’s wishes and faced Anand. My friend Matt Gaffney—a national master and an occasional contributor to Slate—has proposed an alternative system of four major tournaments, doing away with the head-to-head world championship match entirely and replacing it with something akin to the four grand slams of golf or tennis. In between those major events, accumulated rankings points would tell us who’s No. 1. Everyone I spoke to in St. Louis favored this idea. Nakamura brought up Gaffney’s essay unprompted the moment I mentioned I was writing for Slate, and said he’d read it and agreed with it wholeheartedly.

Maurice Ashley—a grandmaster and one of the commentators in St. Louis—has his own novel idea to juice up the game. He’s holding the Millionaire Chess Open in Las Vegas next month, the chess world’s answer to the World Series of Poker. The WSOP allows anyone to enter—so long as you pony up the entrance fee, you can sit at the table with the best players in the world and maybe bluff them once or twice. Likewise, for a $1,000 buy-in, anyone can enter the Millionaire Chess Open and take aim at a slice of its $1 million prize pool. There will be grandmasters there, and also some folks who barely know their Ruy Lopez from their Queen’s Gambit. Spots are still open in Vegas, if that’s the kind of mating you’re contemplating. If I go, it won’t be to play—it’ll be to bet heavily against amateurs like you.

* * *

Caruana won his sixth game against Topalov, and then his seventh in a rematch with MVL. He remained undefeated and undrawn. Onlookers couldn’t believe this was happening.

“He’s not making any mistakes,” said a shell-shocked MVL in a post-game interview. “It’s the most amazing thing I’ve seen by quite some margin.”

“We’re gonna need to start calling him Fabiano Fischer,” suggested Maurice Ashley. One of the live stream commentators theorized “chess fans in the future will ask each other, ‘Where were you in September 2014?’ ”

In his eighth game, Caruana came up against Carlsen. The Norwegian played the black pieces this time, and thus was at a disadvantage. But you could sense that the champ had seen enough from his new, younger rival. Carlsen, employing an unexpected Accelerated Dragon defense, fell behind early but then managed to work a draw. Caruana’s streak of outright victories was over. “It’s an amazing result,” said Carlsen in a post-match interview with Sinquefield Cup commentators. “Even if he doesn’t turn up for the last two games, it would be one of the greatest of our time.”

Caruana did show up, drawing his final two games to win the tournament (and its $100,000 top prize) with a record of 7-0-3, getting 8.5 points out of a possible 10. His victory at the Sinquefield Cup earned Caruana the highest tournament performance rating of all time, crushing even Karpov’s legendary result at Linares. Earth’s finest chess players couldn’t manage to pin Caruana with a single loss. As a result, he vaulted past Aronian in the real-time rankings to become No. 2 in the world. (Carlsen finished in second place in St. Louis, three points behind Caruana, with a record of 2–1–7.) Rumor has it that U.S. chess interests are now trying to convince the U.S.-born Caruana, who now represents Italy, to compete as an American in international tournaments like the Chess Olympiad. “For the moment, I can’t discuss if anything is going on,” he responded when I asked him about the possibility. “It’s private.”

* * *

The day after the tournament closed, Magnus Carlsen made his long-awaited decision. He would play in Sochi in November against Anand after all, just as FIDE had demanded.

Photo by Manjunath Kiran/AFP/Getty Images

Other than a possible general distaste for the way FIDE operates, why had Carlsen stalled? According to chess insiders, he: 1) was unhappy with the size of FIDE’s prize purse, which had shrunk considerably since the previous title event; 2) wasn’t altogether thrilled about the security situation in Russia, given the brink-teetering possibility of a hot war with NATO; 3) was maybe less than psyched to spend a fortnight in a barren, crumbling, Slavic ghost town; 4) was not 100 percent clear about who, precisely, would be funding the event.

This last concern mattered. Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, the extra-terrestrial-philic FIDE president, had at one point suggested the championship could be bankrolled by Alexander Tkachyov, governor of Russia’s Krasnodar region. Tkachyov has managed to secure himself a spot on an EU blacklist by dint of his role in “undermining Ukraine’s sovereignty.” He is under sanction—meaning a travel ban and an asset freeze. Were Carlsen to accept Tkachyov’s dirty rubles, the blowback from goodhearted fellow Norwegians, from politically savvy Western chess fans, and, not least, from disapproving EU officials, might sully the youthful grandmaster’s image.

I asked Carlsen’s manager whether he’d gotten clarification about who would be paying. He responded in an email, “Regarding the money to fund/sponsor the event, we must trust FIDE to be in control. We expect that their finances will be in accordance to international agreements, laws and regulations.” FIDE answered my emailed questions thusly: “Alexander Tkachyov or any other persons sanctioned by the EU or the U.S. are not providing any funds for the match. All sponsorship contracts will be reviewed by FIDE.” The show will go on.

Photo by Rune Stoltz Bertinussen/AFP/Getty Images

It may be that Carlsen received the assurances he needed. It may be that he felt Caruana inching toward his crown, and felt an urge to reassert himself as the champ. Either way, I encourage you to tune in for some of the championship series in Sochi, or for Caruana’s next live-streamed match. Perhaps you’ll get swept up in the beauty of this 1,500-year-old pastime. Start to learn a few openings. Maybe some defenses. Eventually yearn to execute a perfect smothered mate.

It really is a seductive game. At one point during the Sinquefield Cup, I was watching from a quiet viewing lounge on the first floor of the chess club. I glanced over to my left and saw a man sitting alone. It was Rex Sinquefield. I tried to make conversation, but he politely brushed me off. He was utterly focused on watching Caruana play. An orphan turned plutocrat, now transformed back into a little boy watching his favorite game.

I suddenly realized that he’d created this institution, funded this tournament, flown these grandmasters here and housed them, out of the purest, simplest love imaginable. He may not have lured droves of spectators to the event, and may not have reignited the world’s love affair with chess. But for two weeks at least, he helped the world’s most storied game flourish as it once had, with dedicated fans witnessing an incandescent burst of greatness that seemed to come from nowhere.

But maybe we shouldn’t have been surprised to see something we’d never seen before. And by the same measure, maybe we can’t predict what the future holds for chess. After all, any dedicated student—and Rex Sinquefield is one—can tell you that there are more potential variations in a single chess game than there are atoms in our observable universe.