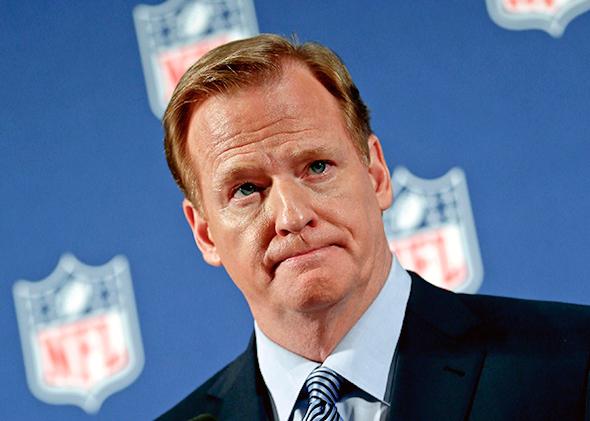

In his press conference on Friday, NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell proclaimed, with all the sincerity one can muster when reading talking points from a political consultant, “We will get our house in order.” Also: “The NFL has to take care of its house.” And: “There are things we need to clean up in our house.”

As Goodell sees it, This Old Football House is a bit of a fixer-upper. I’d say that NFL HQ is something more akin to the six-bedroom Dutch colonial from The Amityville Horror. But even if we tear down his office brick by brick and salt the earth beneath his desk chair to ensure that it never swivels again, that doesn’t help us answer the biggest question raised by the Ray Rice and Adrian Peterson cases. What should a sports league do when an athlete transgresses off the field?

To put it another way: If we went back to first principles, what would a fair “justice system” look like in the NFL? Should the league punish players for crimes at all, and if yes, who should do the punishing? Is it OK to suspend players when they’ve merely been arrested for, but not convicted of, a crime? Should we applaud the NFL (or individual teams) for gathering evidence through extralegal means?

Even if we agree that Goodell has done a miserable job, these questions aren’t easy to answer. Not that Roger Goodell hasn’t tried. In 2007, the commissioner crafted the NFL’s personal conduct policy in response to a flurry of bad press about gridiron criminality. Goodell planted his flag on the moral high ground, writing to one player, “Your conduct has brought embarrassment and ridicule upon yourself, your club, and the NFL.” The commissioner’s message: Only upstanding citizens can bash their brains in on my watch!

Writing in Deadspin last week, Tim Marchman argues that it wasn’t Goodell’s place to come down from Mount Sanctimony bearing rules for player behavior—that the “United States and the NFL both got along fine for many decades without the league commissioner routinely suspending players for violations of a personal conduct policy.” Before Goodell was dinged for being too lenient toward Ray Rice, he was known for being too tough: He suspended Ben Roethlisberger even though the Steelers quarterback—who was accused of sexual assault—was never charged with a crime. This is the problem with the one-man legal system that Goodell’s personal conduct policy created: When a single person plays the roles of judge, jury, and executioner, punishment comes down to personal whim.

So first: I think it’s reasonable for the league to fine and suspend players for actions that affect the game on the field, including hits on defenseless receivers and the use of performance-enhancing drugs. But when it comes to off-field behavior, whether it’s a minor foible or something deadly serious, I don’t believe the commissioner should wield a gavel. And forget Goodell’s proposal for a “personal conduct committee” to help him dole out punishments. On these matters, I’m a federalist: There are 32 NFL teams, and it should be up to each of them to decide what to do with their employees.

This “states’ rights” argument was an easier one to make before ESPN’s blockbuster investigative piece on Friday, which reported that the Baltimore Ravens consciously and systematically misled the NFL and everyone else about what Ray Rice did in that casino elevator back in February. (The Ravens dispute pretty much everything in the ESPN story.) If NFL owners had sole discretion to decide how long their players got suspended, you’d expect them to be more lenient than a dispassionate outside party. Plus, there are plenty of owners who need to get their own mansions in order before they have the standing to suspend anyone for anything. Those include the Colts’ Jim Irsay (who was suspended six games by the NFL for driving while intoxicated), the Cowboys’ Jerry Jones (who’s facing sexual assault allegations), the Browns’ Jimmy Haslam (whose truck-stop company paid a $92 million fine for defrauding its customers), and the Vikings’ Zygi and Mark Wilf (who were found liable in a civil lawsuit brought by their former business partners, with the judge saying there was evidence of “bad faith and evil motive”).

Despite all of those legitimate problems, it still makes sense for personnel moves to be made at the local level. Rice was a Ravens employee. The running back cashed owner Steve Bisciotti’s checks, and he wore a Baltimore jersey, not a generic uniform that said “NFL.”

Even if a franchise isn’t inclined to do the right thing, it’s the team, not the league, that’s the most susceptible to local pressure when it screws up. The commissioner is paid very well to take heat for the owners who employ him—to be the one standing up at a press conference bloviating about the league’s record on sexual assault and domestic violence. But in this new, post-Rice era of populist anti-football outrage, teams can no longer hide behind Goodell’s robes. When the second video came out, it was the Ravens who (finally) moved first, releasing Rice before the NFL suspended him indefinitely.

We’ve seen the same thing across the rest of the league. The Carolina Panthers allowed Greg Hardy to suit up even after the defensive lineman was convicted of assaulting a woman and threatening to kill her. Now, after an unrelenting uproar, the Panthers have placed Hardy on the exempt/commissioner’s permission list, essentially granting him paid leave while his case is on appeal. The same thing happened with the Minnesota Vikings and Adrian Peterson: After announcing that the running back, who faces child abuse charges in Texas, would play in Week 3, the franchise relented to pressure from sponsors, fans, and the press and placed him on the exempt list. The Cardinals’ Jonathan Dwyer, too, has been deactivated by his team for the rest of the season after he was charged with domestic assault.

The San Francisco 49ers have been the exception to this very new pattern of outrage-and-response. Defensive lineman Ray McDonald was arrested on Aug. 31 on suspicion of domestic violence after police found that his pregnant fiancée had “visible injuries.” Nevertheless, the 49ers have kept him on the active roster, continually citing the need to respect “due process.” The team’s CEO Jed York has said, “My character is I will not punish somebody until we see evidence that it should be done or before an entire legal police investigation shows us something.” Coach Jim Harbaugh (the brother of Ravens coach John Harbaugh) added that the team was “not going to flinch based on public speculation.”

There is no perfect solution here. Institutions inevitably act in their own self-interest, and we’re only going to be disappointed if we expect NFL franchises to behave with more integrity and honesty than other corporations. In the end, I think Ray McDonald should not be playing, but I’m also fine with empowering the 49ers to make that decision. If different players are going to suffer different consequences for their off-field actions—and that seems like an inevitability—then it’s a lot fairer and more logical that those punishments reflect the differences between 32 employers and within 32 distinct communities rather than the impulses of an unchecked, essentially dictatorial figure.

Should teams be able to suspend players before they’re convicted? I think so. This is especially true in cases of domestic violence, where the victims often side with the perpetrators and refuse to press charges despite abundant physical evidence: blood, bruises, broken bones. What Goodell has done, to his credit, is carve out a space—the commissioner’s exempt list—for players like Peterson, a purgatory in between taking handoffs on Sundays and being cut without pay. We can all agree that child abuse and domestic violence are abhorrent and, at the same time, that some number of people who are accused of those crimes are not guilty of them. An exempt list, preferably one controlled by the individual teams rather than the commissioner, acknowledges that reality.

What should the commissioner’s role be? Under the current system, Goodell incredibly decides punishments and rules on appeals. A fairer procedure would give him only the second of those two roles—the power to hear an appeal from the NFL Players Association if it believes an individual franchise has punished a player unfairly. Of course, I’d rather the appellate judge not be Roger Goodell. I’m imagining a commissioner who stands above the fray, and who might actually mitigate a suspension once in a while, like former commissioner Paul Tagliabue did when he heard the appeal of the Saints bounty case and vacated the players’ penalties.

So let’s suppose the teams, not the league, have all the power to punish players. Should they also take investigations of player misconduct allegations into their own hands? Fox’s Jay Glazer has reported that the league is indeed looking to create a “special-tasks unit” to conduct its own investigations of off-field contretemps.

This is a terrible idea. Do we really want the NFL to emulate Major League Baseball, which paid $125,000 for stolen documents in an effort to implicate various players for taking performance-enhancing drugs? The league’s push to create a stronger investigative arm reads as an attempt to deflect attention from the facts of the Ray Rice case. The police report that was issued immediately after Rice punched his then-fiancée in the face indicated that … Rice punched his then-fiancée in the face. That should have been enough evidence for the Ravens to put their star running back on paid leave right away. The league and/or the Ravens also could have gotten the video without having to pay off a casino employee. Rice’s attorney had it, and Bisciotti, the Ravens’ owner, admitted on Monday that he just didn’t think to ask for it. Or didn’t want to. Either way, he didn’t need a task force to take on the case.

The NFL isn’t different or special. The teams aren’t different or special. They are employers, with employees, some small number of whom break the law. The NFL needs a disciplinary system that acknowledges that reality, one in which Roger Goodell isn’t the guy holding the scales of justice.