I’ve spent more than a decade stewing over it, rolling the memories around in my head, wondering if it could’ve really been that bad. Now, I’m ready to accept my place in history. Of the thousands of American boys who have played quarterback for their high school football teams, I was the worst.

I went 0–23 as the starting quarterback for John Bapst Memorial High School in Bangor, Maine, a perfectly imperfect record that came during a longer schoolwide run of 41 consecutive losses. The Bapst losing streak began in 1998, when I was an eighth-grader playing quarterback for a middle school team that won one game. It ended in 2003, in the second game of the first season after I graduated. As the guy under center for nearly three full seasons, that streak feels like mine more than anyone else’s.

That’s not to say it was all my fault. Losing was a total team effort. We were the John Bapst Crusaders, and we never came close to the Holy Land. During my three years of varsity football, we did not once have a lead. Our closest defeat was a 6–0 shutout. My sophomore season, the year I arrived at John Bapst and took over at quarterback, we scored 20 points total. During my junior year, we had something of an offensive explosion, averaging more than 9 points a game. We followed that up by scoring 21 points my whole senior year. This was against teams from the smallest schools in eastern Maine, which is about as far you can get, both geographically and athletically, from the high school football hotbeds of California, Texas, and Florida. I did not, to my knowledge, ever play against anyone who was all that good at football. And yet we lost, again and again, almost always by more than 30 points.

Illustration by Robert Neubecker

I won the starting quarterback job my sophomore year, despite the fact that I weighed about 150 pounds and the balls I threw looked like wounded birds fighting a stiff breeze. And yet, I replaced a bigger, stronger junior mostly thanks to two lucky—really, miraculous—plays that I pulled off while still the backup. The first was a 43-yard touchdown scramble in garbage time of a 52–6 loss. I broke a few tackles, reversed field, found a crease, and dived for the pylon to get the score. It looked great, but in reality the only reason I scored was that the other team thought I was down and had given up on the play. Two games later, I came in just a couple of minutes before halftime. We were losing of course and had the ball in our own territory. A few plays in, I threw an 8-yard out well over the intended receiver’s head. Somehow, another of my teammates caught the overthrow and scampered 70 yards for a touchdown. In just a few minutes of playing time at quarterback, I had accounted for all of our team’s scoring up to that point in the season. Nobody seemed to know or care that both plays were complete flukes. I started the next week, and we scored just one touchdown in the remaining five games.

“We thought that you were naturally more creative,” Bruce Pratt, the head coach my freshman year and an assistant my sophomore season, told me recently when I asked why the coaches had made me the starter. “The quarterback was going to be running for his life.”

That was true, at least the running-for-my-life part. I would scramble as soon as the ball was hiked, reversing field three or four times in a single play. I wouldn’t make particularly good passes on the run, nor did I rush for many yards. But I did make the plays last longer. I avoided hulking lineman, pump-faking every other step and spinning away from would-be tacklers. I played, essentially, like somebody avoiding the bulls in Pamplona. And more often than not, the bulls ran me down.

No one ever really taught me how to read a defense, and I couldn’t tell you if our opponents were playing man or zone. We ran a pro-style offense my sophomore year and found more success my junior season by running an old-style T formation, which relied on fakes and trickery to mitigate the fact that we couldn’t block anyone. Every year we had a different head coach. Every year we thought that would mean a fresh start. Every year we were quickly disappointed. In spite of all this, I worked hard. I lifted in the offseason. I practiced throwing on my own time. I wanted to be good. And yet, I was honestly, genuinely, mortifyingly bad.

“You were the perfect quarterback for an awful team,” is how my friend and former teammate Alex Rand explains it. You can’t be as bad at something as I was at football without seeing the humor in it. I created ironic distance between myself and my failure, as all of us Crusaders did. On the bus ride to our practice field (which was on the campus of a mental hospital) we cheered wildly at every red light and stop sign because each second we were delayed meant one fewer spent at practice. The bus driver eventually started rolling through stop signs just to mess with us and disrupt the timing of our applause.

Illustration by Robert Neubecker

Despite all the comedy, both intentional and unintentional, I still feel a kind of low-grade, stomach-knotting despair when I think back on my high school football career. Those losses don’t sting as much as they once did, but I can still feel those failures—and the feeling that I, personally, was a failure.

I’ve never known how to process my high school football experience. We all lost, but as the supposed leader on the field I always felt like the avatar of our ineptitude. Only recently have I realized that there must be others out there like me, schoolboy quarterbacks who couldn’t tell you what it feels like to score more points than the other team. And so I tracked down some other winless high school quarterbacks to see if they felt how I felt, and if they could help me understand the point of all that losing. If nothing else, they helped me understand just how bad I really was. It turns out, yeah, I’m the worst.

* * *

The quarterback position was invented in 1880 when Walter Camp put forward a rule change at the fourth intercollegiate football convention. Camp’s proposal allowed a player on the line of scrimmage to kick the ball backward to initiate the offensive action, creating the possibility of set plays and strategy in a game that had previously been a rugby-style free-for-all. The player that received the ball, the one responsible for making order out of chaos, was called the “quarter-back.”

With the later advent of the forward pass, and the innovations and complexities that came along with it, the quarterback became the play caller and unquestioned leader on the gridiron. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, by the early 1930s the term “quarterback” was being used figuratively to describe a person in a leadership position. With the explosion of the passing game and the increasing cultural valorization of scholastic sports in the post-war era, the quarterback became more important than ever, both as an athletic hero and a sort of apex predator of the high school ecosystem. You don’t have to know a thing about football to understand that the high school quarterback is an enduring American archetype. He leads his team, the school, and the community. He is strong, graceful, and charismatic. He dates the prettiest girl.

A quarterback who never wins a game is an inversion of everything the position represents. He is an illiterate valedictorian, a superhero who lets the bad guys destroy the universe. I was never cool, and I never dated the beautiful girls. Putting on my helmet every day was excruciating on account of the acne minefield dotting my forehead. I was much more likely to get sent to detention for my untucked shirt (a dress code violation) than to win any kind of acclaim from my classmates.

In addition to my role on the football field, I also rode the bench for the varsity basketball team. After practice one day my sophomore year, the upperclassmen were discussing how good the football team would be if they all went out for the squad. “I don’t even know who plays quarterback,” one of them said, before asserting that any of them could probably play the position better than whoever it was who did. Then they all started to wonder: Just who was the quarterback of the football team? I finally offered that it was me, and they politely changed the subject. Our team was so pathetic that even a bunch of high school jocks could see that it was cruel to mock us.

“People do kind of look down at the quarterback and think, You’re the leader and you’re not winning games,” Al Gunderson told me. Gunderson became the starting quarterback for Sturgis Brown High School in Sturgis, South Dakota, toward the end of the 1997 season, his sophomore year. His first start at quarterback was the first of 79 consecutive losses for the Sturgis Scoopers. “I’m sure you felt the same way,” he told me, commiserating. “You kinda felt this pressure on your shoulders and you’re thinking, Man, what am I doing wrong here?”

I was doing a lot wrong. In my 2½ years at the helm, I believe that I passed for four touchdowns and ran for another while throwing a few dozen interceptions. In a season preview published before my senior year, the Bangor Daily News claimed that I completed 34 of 88 pass attempts my junior season. I’d like to confirm those numbers, but my former coaches don’t have statistics or film from those seasons. This, it seems, is pretty common.

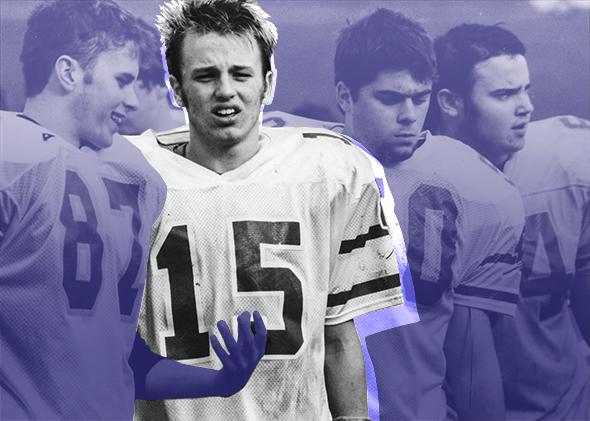

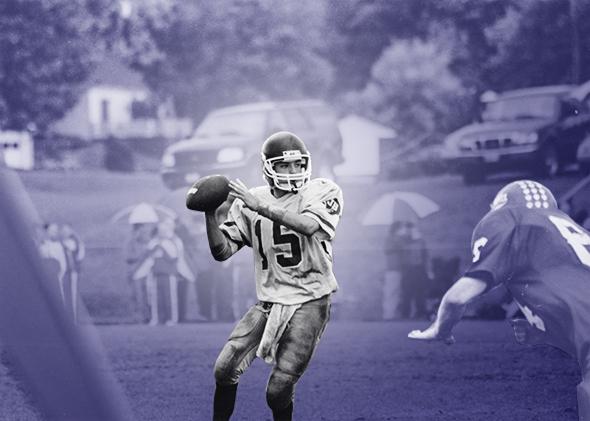

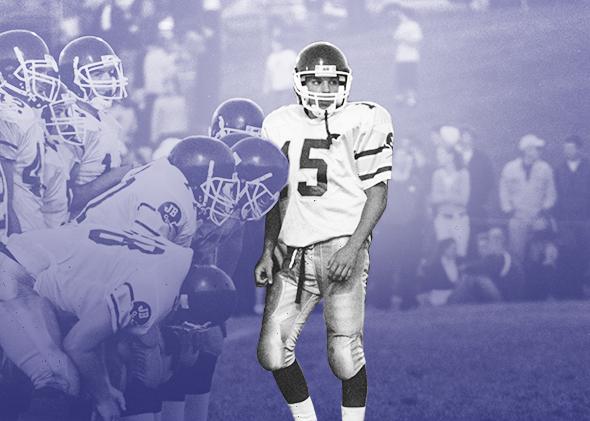

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo courtesy of Josh Keefe.

Nobody keeps track of statistics for terrible high school teams. The history of scholastic sports is written not by but for the winners. No one wants to make a high school kid feel bad about losing. One post-game newspaper write-up I unearthed praised a defense for picking off three passes but was careful not to mention the quarterback who threw them: me. (The box score of that game indicated that I completed four passes to go along with my three picks.) The National Federation of State High School Associations, the website MaxPreps, and the Maine Principals’ Association (the governing body of Maine high school athletics) couldn’t provide me any information about long losing streaks and the quarterbacks who were a part of them. I was told they didn’t track “negative” statistics. Our streak, like many high school football losing streaks that didn’t approach a national or state record, was only quantified and discussed in print when it ended, when it could be celebrated as an accomplishment by a tough group of kids who refused to give up.

The players and coaches who never got that win, however, don’t get that acclaim. And some of them don’t want to rehash all those bad memories. “Who’d want to talk about that?” Cleveland Dansby, the former head coach at Phoenix’s Carl Hayden Community High School asked me when I sought his help in finding quarterbacks to interview. Dansby took over the team in 2005 when it was 24 games into what would eventually become a 66-game losing streak. “That’s embarrassing,” he said.

“You want to give a kid the experience of success, that’s what keeps them going,” Dansby explained. He knew what success felt like: Dansby led South Mountain High School to the 1993 5A state championship game (and coached future NFL defensive backs Terry Fair and Rashad Bauman) before moving on to rebuild Carl Hayden’s program in the 2000s. “Put a kid in a position to be successful and that kid will flourish. But if you keep him around negative stuff, where he doesn’t have a chance to win, what are you doing to that kid?”

I wondered that myself. The sad thing was, so did our opponents.

We would often get beaten so badly in the first half that the clock would run continuously after halftime as a form of mercy. In addition to fielding their JV teams in the second half (and sometimes their freshman by the fourth quarter), our adversaries would sometimes stop returning punts and let us kick the ball into an empty defensive backfield, where it would roll around and run a bit more time off the clock.

Illustration by Robert Neubecker

I assumed that this kind of humiliating compassion was a common experience for losing teams. “No, we never got any of that,” Gunderson, the former Sturgis quarterback, told me. It turns out that the John Bapst Crusaders weren’t just bad. We were bad relative to teams that accumulated losses with historic consistency.

“That is classic,” Gary Marx told me when I explained the running-clock scenario. Marx, who’s now a reporter for the Chicago Tribune, was the starting quarterback for the winless 1973 Harvard School (now Harvard-Westlake) team in Los Angeles. “I don’t remember anybody taking mercy on us,” Marx continued. “They just pounded on us and laughed at us, I think. It was take no prisoners. We were the sacrificial lambs.”

We felt like sacrificial lambs too, in part because every away game seemed to be our opponent’s homecoming. Teams planned celebrations of school and community pride around the nights we came to town.

Still, at least we had a roster that allowed for substitutions.

“My senior year we played [eventual 1993 Georgia Class A state champion] Lincoln County, and we went there with maybe 12 people,” Chris Kelley told me. Kelley’s Glascock County High School lost that day by the score of 72–0. But that was just one game. Kelley was a three-year starter for Glascock County in Gibson, Georgia, which lost 82 straight contests from 1990 to 1999.

“I got rid of it quick,” Kelley told me when I asked about his quarterbacking philosophy. Now he is the head coach at his alma mater, the smallest public school in the state to field a high school football team. He’s entering his 13th year as the team’s head coach, which included an 8–2 season in 2008. “We’re underdogs,” he told me. “Always have been.”

What made our losing so frustrating was that—unlike Chris Kelley and Glascock County High—we had no institutional disadvantages. Sure, we had a different coach every year, and yes, a lot of the kids had never played football before coming to John Bapst. But very little changed between when I graduated in 2003 and when Bapst won a state championship in 2008. The biggest differences: a coach who stuck around, a star running back, and a quarterback who won conference player of the year.

My brother Dan, who’s now 23, was a junior receiver and defensive back on that title-winning team. As a 10- and 11-year-old he went to my games with our parents and watched me lose. “I remember the other kids who went to Bapst and played other sports were always in the stands and always making smartass comments,” my brother recently told me. “I remember always being so mad and yelling at them, ‘Why aren’t you playing?’ ”

By the time Dan was on the team, Bapst had some serious athletes. Reporters came to their practices. John Bapst football became something of a local sensation. “It was just because you guys were so bad and we had won a state championship,” Dan told me. “[The losing streak] made it 1,000 percent more miraculous.” You’re welcome, brother.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo courtesy of Josh Keefe.

Given my 0–23 record, my lack of even mediocre statistics in defeat, and our team’s complete ineptitude in spite of relative parity with our opponents, I am confident in saying I was the worst high school quarterback of all time. Sure, there was probably a kid here or there who had to fill in for an injured starter and had even less of an idea of how to run an offense than I did, but he wouldn’t have lasted long. Longevity counts for something in this sort of sports debate, and I never missed a start. I am the Cal Ripken Jr. of losing quarterbacks. Chris Kelley had more losses than I did, but it’s fair to say that Kelley, who played in football-mad Georgia, would’ve won some games playing in eastern Maine, where making it to Division III college football was a big deal and the tackles were more like aggressive hugs than real hits.

And so, wearing the crown, I wonder what the point was. I worked really hard for three years to win a game. There was nothing in this world I wanted more. I prayed for wins after I stopped praying for anything else.

Illustration by Robert Neubecker

After our last game, a relatively close 21–6 loss to our rivals Orono High School, I was overwhelmed by emotions I didn’t understand and couldn’t express. I was sad, disheartened, and demoralized, but since I had felt that way for most of three years, I was also relieved that it was finally over—that it was now someone else’s responsibility to lead the John Bapst football team against mill town teams that called us “purple faggots.” I didn’t cry that day. I sat on the dark bus home in stunned silence, that strange mixture of sadness and relief leaving me unable to articulate anything meaningful when I high-fived and hugged my fellow seniors as we left the locker room for the final time. It was hard to see any purpose in what we had gone through. We had humiliated ourselves publicly while getting physically beaten in the process. And there was no payoff at the end.

But now, years later, I wonder if maybe there was something to be gained from never winning. My fellow losing quarterbacks certainly think so. “I learned so much from it,” Gunderson, who is now a chiropractor back in Sturgis, South Dakota, told me. “You get your butt kicked and yet kids show up every single day, and fight every day, and want to work hard every day. That’s the real world. I feel I’m a better person for it.”

“We had a few kids that quit about halfway through the season, they just didn’t want to do it,” Gunderson added. “And I felt bad for them because if they quit during something like that, you know they are going to quit later in life, too.”

“In football, I don’t care if you’re on a state championship team, you’re going to get knocked down from time to time,” Kelley said. “You’re going to get knocked down from time to time in life, too, but do you get back up enough? That’s the question. … You either get up or you don’t.”

It’s true but banal to say that losing teaches you important lessons—nobody disputes that. But every team faces adversity. Here’s what I’ve never understood: How does losing every game teach you anything that going 2–7 doesn’t?

I think I finally have the answer to that question. It didn’t come easily—I struggled for years to see just what the “life lesson” was that parents and coaches insisted I had learned. I had to enter the real world before I could grasp it, knowing what it was like to be penniless (more than once), working terrible jobs, sleeping on couches for months at a time, and getting a seemingly endless trail of rejection letters in response to my writing. I had to get dumped. I had to lose some hair. Now, as an adult, I get it.

Life is a hopeless fight against loss and failure. We are all going to die, as will all of our loved ones. Getting beaten continuously on the football field, sometimes brutally so, illuminates this existential struggle. It teaches you to find joy in what you’re doing, and the people you are doing it with, in spite of the inevitable outcome.

As a culture, we try to make every kid feel like a winner. Maybe we should also give every child a task that he will fail at again and again, along with teammates to fail with. He might learn to detach himself from winning and losing and learn the value of putting up a good fight. He might learn that trying and failing to achieve a long-shot dream is better than settling for a passionless life. He might learn how to lose, which is a valuable skill that this life provides no shortage of opportunities to put into practice, and yet shockingly few people know how to do well.

I know there are quarterbacks out there who won every game, who got the girl, who made it on TV and got their names on statues. It must have been great, conquering a fantasy world. But I learned something about living in ours.

I’m proud of all the losing I did. Not everybody keeps at it until they’re the worst to ever play the game.