Last year, Sports Illustrated soccer writer Grant Wahl donned a tan fedora, tweeted a picture of himself standing field-side holding a mike, and wrote: “Dent McSkimming reporting on the scene from World Cup 1950.” Wahl was referring to the only American reporter on hand for one of the biggest upsets in tournament history: USA 1, England 0.

In addition to having a name fit for an Anchorman sequel, McSkimming was the rare American sportswriter who championed soccer in the early- and mid-20th century. He started working for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch after World War I and wrote for the paper into the 1960s. In those years, St. Louis was one of the few cities where soccer was played with great frequency and—for the United States at least—played well. McSkimming loved the sport. He watched games from the far corner of the stands because he couldn’t bear listening to other reporters talk politics or baseball. “Turn your head a second,” McSkimming said, “and you’ve missed what could be important action.”

The image of McSkimming as the lone, intrepid hack chronicling the band of upstart Americans is a staple of the narrative surrounding the 1950 U.S. World Cup team. The recently published Mammoth Book of the World Cup reports that McSkimming “reported back the exciting news” of the Americans’ victory over England in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, “with great pride.” McSkimming’s bio on the National Soccer Hall of Fame website says that, even though he was in Brazil on vacation rather than on assignment, he “covered the games as part of his decades-long campaign to help keep soccer in the public eye.” In a tribute column to McSkimming upon his retirement from the Post-Dispatch, a colleague wrote that, in reporting on the 1950 World Cup, “Dent achieved the greatest sports thrill of a career that saw him covering a major league ball club at 18 and the Willard-Johnson heavyweight title fight in Havana at 19.”

Other accounts give McSkimming an outsize, dramatic role in the events in Brazil. In The Game of Their Lives, a 2005 movie about the 1950 U.S. squad, McSkimming, played by Patrick Stewart, narrates the story of the shocked-the-world team; asked about being the only American reporter at the tournament, the McSkimming character replies, “Just doing my job.” A community news site in Roanoke, Virginia, wrote that when the U.S.-England game ended, “McSkimming pushed through the crowd and found a phone. Called his editor. He had to be the first reporter to get the news of this miracle into print. He needn’t have worried. The next morning, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch was not just the FIRST paper to break the news, it turned out to be the ONLY U.S. paper to do so.”

That’s not quite true. The Post-Dispatch was an afternoon newspaper at the time. Here’s what it published on June 29, the day of the game:

Courtesy of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch

That’s it. The three-deck headline—“U.S. Soccer Team Upsets England, 1-0”—took up more real estate than the one-sentence article by the wire service United Press. The story was placed just below the play-by-play recap of the St. Louis Cardinals’ 6–1 loss to the Chicago Cubs and just above a report on girls’ softball.*

The next day, June 30, the Post-Dispatch printed a longer account of the victory over England, reporting that “the underdog Americans dominated the attack during the entire game and forged a rock-ribbed defense when the British fought back in an effort to tie the score.” That story carried a Belo Horizonte dateline but no byline. (The New York Times that day published an extensive Associated Press story, which misidentified the U.S. goal scorer.) On July 3, under the headline “U.S. Eliminated in Soccer Tourney,” the paper printed eight paragraphs about the 5–2 loss to Chile in Rio de Janeiro. That article didn’t have a byline either but was labeled “Special to the Post-Dispatch.” The paper’s four subsequent stories about the tournament were short, wire-service dispatches.

So where was McSkimming? Geoffrey Douglas’ 1996 book The Game of Their Lives, on which the movie was based, mentions McSkimming just once, to tell the story of how he paid his own way to Brazil. The book doesn’t quote or cite anything written by McSkimming. The 2010 book Soccer Stories by Donn Risolo says McSkimming was “taking in the game as a tourist” and notes that the Post-Dispatch ran a wire-service account of the England game. Sports Illustrated senior writer Alexander Wolff told me that in researching his 2010 feature about the tragic story of Haitian immigrant Joe Gaetjens, who scored the U.S. goal against England, he “didn’t find anything … contemporaneous that McSkimming wrote.”

That’s because McSkimming didn’t file a word from Brazil under his own byline. A possible reason: He was pissed off at his bosses.

According to a 1997 Post-Dispatch story by Keith Schildroth, on the first Saturday in May 1950, McSkimming won the office Kentucky Derby pool, “collected his winnings, worked half his shift, and took a long lunch break”—a break that would last two and half months. McSkimming, Schildroth wrote, was upset that the sports editor, John E. Wray, wouldn’t pay to send him to Brazil. His disappointment was understandable. At 53, McSkimming was a respected veteran on the newspaper’s staff and the dean of American soccer writers. Plus, there was a major local angle: The U.S. roster included six players from St. Louis. McSkimming had been so eager to cover the tournament that he studied Portuguese three nights a week at Saint Louis University.

Once in Brazil, perhaps a beefed McSkimming decided he wasn’t going to file on deadline for his cheapskate paper, even to report history. But what about those two uncredited stories? Newspaper byline rules could be stringent and arbitrary, and these were different times. Maybe the Post-Dispatch withheld credit from McSkimming because he was on vacation. Maybe the stories were too short to merit a byline. But McSkimming had joined the paper in 1922. Wouldn’t he have wanted credit for his work, and wouldn’t the paper have wanted to showcase the fact that its star soccer writer was on the scene? Another, more fanciful, theory: McSkimming filed the short game reports out of journalistic obligation and withheld his byline in protest. Or maybe the paper made him file and withheld his byline in punishment. Or maybe someone else wrote the stories.

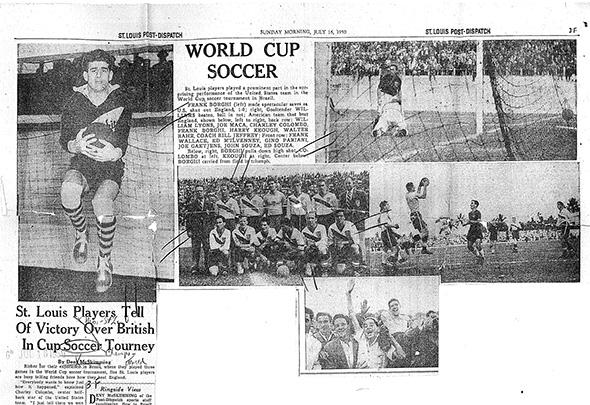

While the story behind those two uncredited articles isn’t clear, we do know that when McSkimming returned home—his vacation over—he filed two stories about the tournament. The first was published on Sunday, July 16. (This happened to be the day that Uruguay stunned Brazil 2–1 in the World Cup final before more than 150,000 fans in Rio’s Maracaña Stadium.) Under the headline “St. Louis Players Tell of Victory Over British in Cup Soccer Tourney,” the article began:

Richer for their experience in Brazil, where they played three games in the World Cup soccer tournament, five St. Louis players are busy telling friends here how they beat England.

“Everybody wants to know just how it happened,” explained Charley Colombo, center halfback star of the United States team. “I just tell them we won because we scored a goal and then tied them up so they couldn’t get through us.”

Harry Keough, who played at right fullback in all three games, against Spain, England and Chile, adds another thought to Colombo’s terse comment.

“I don’t mind saying we were almost sorry to beat the English team that day in Belo Horizonte,” says Harry. “We felt it was going to be a terrible blow to them, and we knew we were not yet strong enough to win the championship. But we beat them and in the last five minutes came close to making it 3-0 instead of 1-0.”

A note accompanying the 16-paragraph story explained that McSkimming “of the Post-Dispatch sports staff vacationing” had flown to Brazil with the team, watched the England game, and interviewed the players on the journey home.

Courtesy of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch

The paper devoted the top of Page 3 of its Sunday sports section to the story, along with five photographs, one of a jubilant U.S. goalkeeper Frank Borghi being “carried from the field that day on the shoulders of his hero-worshippers.” McSkimming praised the team’s “brilliant performance” against England but criticized its play against Chile, chiding halfbacks Ed McIlvenny and Walter Bahr for “fruitless running about.” McSkimming concluded that the tournament was a “partial success” and that U.S. soccer officials “look hopefully to other triumphs in international competition.”

McSkimming’s second and final World Cup story was about Prudencio “Pete” Garcia, a St. Louisan who worked as a linesman in four matches in Brazil. (“It was rarely necessary to warn a individual of dangerous conduct,” Garcia said.) It ended with a hopeful note that, after the team beat mighty England, U.S. soccer officials “are convinced that such success might be repeated if adequate coaching is offered American boys.”

The United States wouldn’t return to the World Cup for 40 years. The lack of bylined reports from Brazil didn’t harm McSkimming’s reputation among the soccer cognoscenti. Just a year later he was inducted into the National Soccer Hall of Fame. McSkimming died in St. Louis in 1976 at age 79. In 2014, 64 years after one American reporter attended the World Cup on vacation, approximately 100 credentialed media members traveled from the United States to cover the tournament.

Special thanks to St. Louis Post-Dispatch news research archivist Jennifer Selph.

Correction, July 2, 2014: Due to a photo provider error, the caption of the image from the 1950 World Cup match between the U.S. and England misidentified two players. They are Roy Bentley and Ed McIlvenny, not Tom Finney and Walter Bahr.

Correction, July 3, 2014: This story originally misstated the result of a baseball game from 1950. The Cardinals lost to the Chicago Cubs 6–1; they did not beat them by that same score.