The Spurs play a beautiful game. They show the value of hard work, team play, and humility. San Antonio has one of the best coaches in pro sports, and their general manager is a genius. All of these statements are true, and they merge to form a positive feedback loop. The players work well together because their GM, R.C. Buford, did a great job acquiring talent, which makes the team more successful, which makes more players buy into Gregg Popovich’s team concept. Greatness begets greatness year after year, and the next thing you know you’ve won five NBA titles in 15 years.

This isn’t how things have typically worked in the NBA. When he was the coach of the Los Angeles Lakers, Pat Riley—now the president of the Miami Heat—said his team succumbed to the “disease of more.” When the Lakers won, Riley explained, his players got more selfish. As Bill Simmons described it in a 2007 column, “Everyone wanted more money, playing time and recognition. Eventually they lost perspective and stopped doing the little things that make teams win and keep winning.”

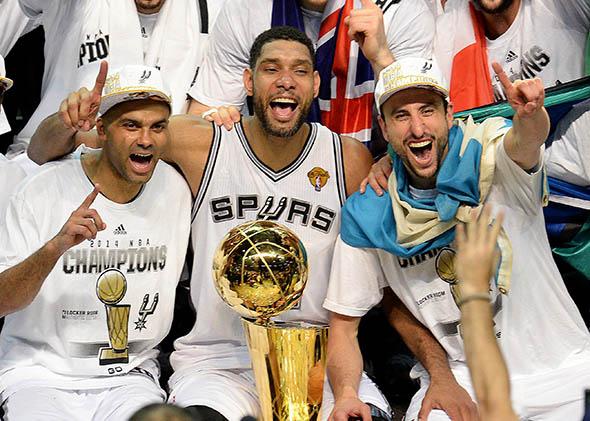

In San Antonio, the opposite has happened. As the Spurs’ Big Three of Tim Duncan, Tony Parker, and Manu Ginobili have gotten older and more established, they’ve willingly taken on less, playing fewer minutes and taking smaller salaries. These sacrifices have allowed San Antonio to pay for and develop valuable complementary players like Boris Diaw, Tiago Splitter, and Marco Belinelli. It’s a simple salary-cap calculus: There would be no team ball if Duncan, Parker, and Ginobili weren’t team players when it came to their own contracts.

Though it started with a bit more pomposity and circumstance, the same basic story can be found in Miami. LeBron James, Dwyane Wade, and Chris Bosh all took less than the NBA’s maximum salary to team up together on the Heat. The trio learned to play together and have won two championships in the take-my-talents-to-South-Beach era—one more than the Spurs in that time. Now that San Antonio has taken Miami’s trophy, how will the Heat strike back? There’s now speculation that the Miami trio—all three of whom can opt out of their contracts this summer—could agree to further salary reductions to help bring in a fourth amigo like Carmelo Anthony.

Elite NBA players are now effectively serving as their own general managers. By slashing their own earnings to fit themselves and their teammates under the salary cap, they’re sacrificing money in addition to the lucre they’ve already given away in the league’s collective bargaining agreement. While Detroit Tigers slugger Miguel Cabrera signed a deal that will pay him what averages out to $29 million a year, James makes $19 million annually, which is just below the league’s maximum salary.

Though the players agreed to this system—it was collectively bargained, after all—it puts them in the awkward position of having to sacrifice salary in order to preserve their public image. If guys like Duncan and James were paid closer to what they’re worth in the NBA’s version of an open market, they’d risk being labeled selfish superstars who care more about money than winning. (I call it the NBA’s version of an open market because we need to ignore the fact that LeBron James would make $50 million a year in a truly open, capless market.) But if you take less and win more games, you’re praised for your selflessness—well, at least if you’re in San Antonio.

NFL players face the same salary-capped dilemma. Seattle Seahawks fans are not aggrieved by the fact that Super Bowl–winning quarterback Russell Wilson made a mere $500,000 in 2014. Rather, they’re overjoyed that he’s so underpaid, which allows the team to spend that much more on other positions. And Saints fans aren’t supporting tight end Jimmy Graham’s quest to be paid as an upper-crust wide receiver rather than a middle-class tight end—the less money he gets, the better players the team can put around him.

For some players, taking less money is the best possible decision. I’d imagine that Tim Duncan has more cash than he’ll ever need, and that another championship ring will bring him more happiness than another couple of million dollars. It’s also hard to empathize with a player who’s already superrich and passes up the chance to be super-duper rich. But when a player doesn’t get paid what he’s worth, much of that money—the portion that doesn’t end up in the pockets of lesser NBA talent—just ends up in the pocket of an even wealthier owner, a fellow whose earnings aren’t capped in any way, and who could sell his franchise for north of $1 billion whenever he gets bored or gets caught being a racist.

So, let’s praise the Spurs’ selflessness on the court—their crisp passing, movement without the ball, and tireless team defending. But the Big Three’s willingness to reduce their salaries isn’t something that should be celebrated. Instead, let’s stump for a system in which a team like the Spurs can win a title by playing a beautiful game on the court, and NBA legends like Tim Duncan, Tony Parker, and Manu Ginobili get paid something closer to what they’re worth.