Unlike some other European countries, Germany has no great history of expeditions to South America.

The last time a German World Cup team played here was in 1978, in Argentina. West Germany came as world champions and went home after the second round. The most memorable moment of the team’s campaign came in the match against the Netherlands. West Germany was leading 2–1 when Dutch winger René van de Kerkhof broke through and shot past German keeper Sepp Maier. The blond German defender Rolf Rüssmann flung himself full length and tried to punch the ball clear, but he couldn’t quite stop it going into the net. That German side wasn’t quite good enough to win the World Cup, but Rüssmann had at least proved that they wouldn’t think twice about doing what had to be done to win it. He had shown their hearts were in the right place.

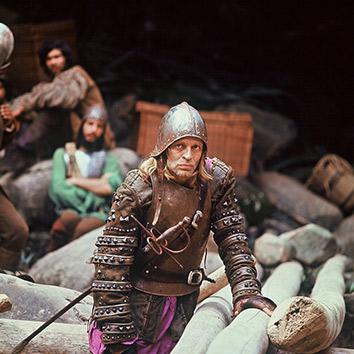

Germany’s most successful forays into South America in the 1970s were made not by their footballers but by their filmmakers. In 1972, director Werner Herzog led a cast and crew that hailed from 16 different nations on a five-week shoot in the Amazon rainforest. The resulting film, Aguirre, the Wrath of God, starred Klaus Kinski as the eponymous Aguirre, a mad conquistador obsessed with finding El Dorado. Aguirre was arguably more psychologically stable than the man who played him. Kinski, the most famous German actor of the 1970s, was a maniac whose frequent tantrums made him almost impossible to work with.

Keeping him on the set took all of Herzog’s resourcefulness. He once threatened to shoot his star if he followed through on one of his threats to quit. One of their confrontations was recorded by a sound engineer without Kinski or Herzog knowing it. Herzog had presumed to advise Kinski on some matter pertaining to the scene. Kinski didn’t like this.

“Don’t give me stage directions! I can’t stand that! I can do it by myself! If you think you’re better, why don’t you do the acting!” Kinski was working himself up into a rage. “You’re always for half-measures. You’re scared shitless of the consequences! If you want someone to be excited then let him get excited! I’ll act it the way I want to!”

Herzog interjected: “OK, but we have to …”

“Keep your half-baked advice to yourself! You’re no director! You have to learn from me! You’re a beginner! A dwarf’s director, not a director for me!”

“Now, don’t insult me …”

“Insult you?! You couldn’t insult me more than by trying to direct me!”

And so on.

Courtesy of Werner Herzog Filmproduktion/Shout! Factory

Herzog later explained: “I ought to say that all the hysteria that Kinski introduced was turned to productive ends. Maybe that’s the main point. Of course it sounds embarrassing for him, or embarrassing for me, it depends. But whenever Kinski really got going, hysterical as hell, we tried to start shooting quickly, and he gave it something that perhaps no one else in the world could have put into a scene. I think that’s what counts.”

The world has grown more polite since the 1970s. When Luis Suarez pulled a (successful) Rüssmann in the World Cup four years ago, he was condemned by half the world. And if Christopher Nolan ever threatened to shoot Christian Bale, Bale probably wouldn’t believe him. But even today, we shouldn’t underestimate the importance of creative tension, and a certain ruthlessness.

* * *

The 2014 German World Cup squad goes to South America far better equipped than either Helmut Schön’s 1978 team or Herzog’s crew in 1972. With Europe’s most impressive suite of corporate sponsors, Germany could afford to build its own bespoke World Cup training base on Brazil’s Atlantic coast. The team’s slogan is Bereit wie nie! Ready like never before!

The Germans’ 54-year-old coach, Joachim Löw, has become one of the most recognizable figures in international football, with his carefully curated touchline outfits and shiny helmet of lustrous black hair. His youthful looks are a godsend for national team sponsor Nivea, which uses Löw in several commercials. “It’s a long time since men’s cosmetics were considered uncool,” he said in a recent interview with Nivea Men.

It’s not every day that a leading international coach is expected to give quotes to a leading cosmetics brand, but in the weeks leading up to a World Cup a man in Löw’s position has to do a hell of a lot of interviews.

Germany’s biggest tabloid, Bild, devised a feature in which 50 German world champions from various disciplines each put a question to Löw.

Most of the questions were predictably innocuous. Pole-vaulter Raphael Holzdeppe wanted to know the riskiest thing Löw had ever done (climbing Kilimanjaro) while canoeist Ronald Verch wanted to know what Löw would have been if he hadn’t become a football manager (he dreamed of being a pilot). 1990 World Cup winner and victim of male pattern baldness Jürgen Kohler asked Löw how a man of his age got to have such enviably full, dark hair (sorry Jürgen: it’s just good genes).

It was left to former world middleweight champion Felix Sturm to pose a somewhat more awkward question.

“In boxing, it’s always all or nothing. Would you see anything other than winning the World Cup in Brazil as a defeat?”

“Not necessarily,” said Löw.

Löw told Sturm that in football, you need both skill and luck. You could, for instance, play well, then lose on penalties. “We could end up disappointed, but that doesn’t mean we will have disappointed,” he explained.

The coach knows that such Jesuitical distinctions are unlikely to appease a football nation that is hungry for its first tournament win since 1996. Maybe that’s why he has seemed unusually downbeat at times during this buildup.

“We have a chance to win the tournament,” he told Stern, “and likewise, so do several other teams—but nobody wants to hear this.”

Indeed, the German public rates the squad very highly. It’s not unusual to hear the claim that this is the most-talented squad any German coach has taken to a World Cup.

It’s no use for Löw to argue that injuries have left them some way short of full strength, that torn ankle ligaments have robbed him of a brilliant talent in Marco Reus, that key players like Philipp Lahm, Bastian Schweinsteiger, and Sami Khedira are still short of full fitness with the opening game days away.

These are just the normal problems any World Cup coach has to deal with. The tournament is full of wounded warriors. Stars like Cristiano Ronaldo, Luis Suarez, and Yaya Touré are all struggling with injuries. Their coaches don’t have as much talent in reserve as Löw does.

Germany has won three World Cups and yet many Germans think this is their best ever squad. If this squad fails, what would that say about Löw?

“When you win,” Löw told Stern, “you’re celebrated as a messiah, the savior of the whole nation. And when you lose, you’re public enemy No. 1.”

In any case, Löw says, his legacy will not be defined by success or failure in any given tournament. You need to take account of the bigger picture.

“My salvation doesn’t depend on these days in Brazil. One win more, one defeat more. There are other important things: family, friendship, values … and I think we have evolved football enormously,” he says.

But since Germany used to win tournaments all the time, and now they don’t, some are asking whether it’s been the right kind of evolution.

* * *

These days, international coaches tend to work in a two- or at most four-year cycle. Löw has been on the national team staff for 10 years and has been the head coach for eight.

He has had four major tournaments with Germany—the 2006 and 2010 World Cups and the 2008 and 2012 European Championships—one as assistant to Jürgen Klinsmann and three as head coach. There are two ways to look at his record.

One view is that his team has reached three semifinals and one final, winning acclaim for its style and new admirers around the world. The other view is that it’s a four-time loser.

After Germany’s impressive performances at Euro 2008 and the 2010 World Cup, Löw could have left to manage a major club side, but he stuck with it because he was sure his team was on the cusp of winning something big.

Germany’s long wait for a title was really supposed to end two years ago, in the European Championships in Poland and Ukraine. Germany beat Portugal, the Netherlands, and Denmark in the group stage and crushed Greece in the quarterfinal. Their eyes were on the final against Spain, the team that had beaten them in the final of Euro 2008 and in the semifinal of the 2010 World Cup. This time it was going to be different.

Except Germany ran straight into an Italian sucker punch in the semifinal. Italy had the craft and cunning of Antonio Cassano and Andrea Pirlo, the stubbly ruthlessness of Giorgio Chiellini and Gianluigi Buffon, the explosive speed and power of Mario Balotelli. They made Germany look like a bunch of college kids.

A nation struggled to come to terms with defeat. How could this have happened? Where was the guile? Where was the power? And a familiar theme began to emerge: Where were the leaders? Where were the Real Men?

* * *

The question of why Germany no longer wins has many answers. The simplest explanation is that other teams, such as Spain and Italy, have been better. (Particularly Spain. Germany might have dodged a bullet or four by losing that 2012 semifinal. Spain had been saving its best for the final. It was Italy’s worst defeat in 55 years.)

As an answer, “Spain is just better” might be correct, but it’s too simple to be satisfying. So a debate has developed around the personal qualities of this generation of German players as compared with the serial winners of the past. As Lothar Matthäus recently told World Soccer magazine: “[T]he only thing we lack is the nasty characters.”

When Matthäus talks about nasty characters, he means guys like him. Someone who is prepared to do what it takes. Most of all, someone who is prepared to lead. There is a special vocabulary for this. The usual German word for “leader,” Führer, isn’t used much in this context. Instead, people complain about the lack of a Führungsspieler (leader-player), Führungsfigur (leader-figure), and sometimes even Leitwolf—literally “lead wolf.”

Germany once drew on an apparently inexhaustible supply of Leitwolfs. The 1982 squad alone had men like Matthäus, Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, Felix Magath, Uli Stielike, and Paul Breitner, any one of whom would probably have been the captain and undisputed alpha male in any other squad. The center-forward was Horst Hrubesch, whose mere name sounded like it would probably beat you in an arm-wrestling contest. Hrubesch’s nickname was “the Header Monster.”

Photo by Boris Streubel/Getty Images

The difference between the old-school German teams and the team of today is best summed up by the contrast between someone like Hrubesch and Mesut Özil, the skillful Turkish-German playmaker who would have been prevented from representing the sides Hrubesch played in by the old German nationality laws.

Özil is so gifted that everything he does on the field looks absolutely effortless. This is both his blessing and his curse. When things are going against his team, some fans have a tendency to become irritated by the fact that Özil, with his drooping eyelids and slouching shoulders, looks like he doesn’t care enough. Özil’s Körpersprache—his body language—has become the focus of national debate.

In May, Löw told Kicker magazine that Özil needed to work on that body language. Then the former national team captain Michael Ballack chimed in, repeating that Özil needed to massively improve his body language.

Nobody had ever questioned Ballack’s body language. But then Ballack is more in the traditional Leitwolf mold: 6 feet, 2 inches with a highlight reel full of 30-yard shots and massive leaping headers. His shoulders were probably physically incapable of slouching at an Özil-ian angle.

The current German captain, Philipp Lahm, has taken issue with the principle that every good team needs a Leitwolf. The German team that failed at Euro 2004 had two: Michael Ballack and Oliver Kahn (a Kinski-like figure who can easily be imagined in a steel helmet, tossing a monkey into a river).

Analyzing Germany’s 2004 group stage exit, Lahm wrote in his 2011 autobiography that their failure had demonstrated the bankruptcy of the principle of the “so-called Führungsspieler.” The problem, according to Lahm, was that if all the authority was bound up with the coach and the on-field Leitwolf, the other players were not encouraged to step up and take responsibility. “It’s becoming apparent that a new way of thinking, a commitment to collective responsibility, to flatter hierarchies, is necessary in order to be successful in modern football.”

The problem is that so far, flatter hierarchies haven’t won any trophies for Germany. Annoying as it is for Lahm to have to listen to the old-timers grumbling that he and his teammates aren’t mean enough (meaning man enough) to do it, the only way to shut them up is to win the World Cup.

Löw is also a flat-hierarchies man. Asked by those great chroniclers of the German World Cup adventure, Nivea Men, whether he assessed candidates for his squad purely on footballing ability, he gave a thoughtful response:

Of course, that’s very important. Can the player implement what the coach is looking for? But when you’re at a tournament like the World Cup, you also ask: Which players can give us energy? Which players are tolerant of frustration, if they sometimes don’t play? Which players can promote competition, which players can withstand it? And: Which players are perhaps a little too egotistical? We are away with a big group for several weeks. … For this team, there are certain values to be considered: respect, tolerance, discipline, reliability, integrity, humility, ability to concentrate. If a player has flaws in these areas, the group suffers.

You wonder whether Löw is quite sure what he’s looking for. On the one hand, Özil has been criticized for not strutting about the field like a Leitwolf. On the other hand, the coach says he’s looking for sociable, well-adjusted types who won’t kick up any trouble during five weeks on the road.

If Werner Herzog had cast his movies according to the Löw rulebook, Klaus Kinski would plainly have been the last man on earth he’d have hired. And quite possibly nobody outside the German-speaking world would ever have watched Aguirre.

It’s not as though there’s an actual footballing Kinski out there who’s been excluded by Löw for being unable to get on with his teammates. It’s more the romantic ideal of what Kinski represents—the ungovernable passion, the untrammeled egotism, the demonic energy—that feels like it’s been forgotten about.

All these qualities were evident in the Germanies of Breitner, Rummenigge, Matthäus, even Klinsmann. They have not yet shone through in the Germany of Lahm, Özil, Schweinsteiger, and Mertesacker.

The ongoing preoccupation with the Führungsspieler and the Leitwolf reflects a widespread suspicion among Germans that their team is simply too nice. Can Löw solve the problem by getting them to be even nicer?