Who makes the game?

Of all the pathetic and debased phrases uttered by soon-to-be-former Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald Sterling on what’s now the most infamous conversation in the history of professional basketball, this question may have inadvertently been the most potent. Sterling was asking it rhetorically: In his mind the answer is clearly him, as opposed to his players, to whom he “give[s] … food, and clothes, and cars, and houses.” To the fans who watch the NBA, to the players who play in it and the coaches who coach in it, this suggestion seems as insane as it is despicable.

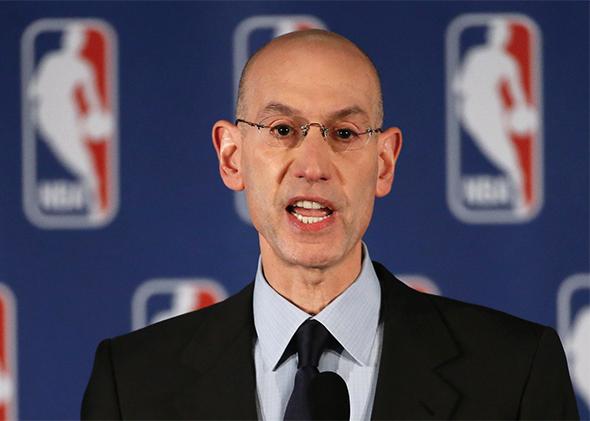

And now we can add Adam Silver to our ranks, thank goodness. The NBA’s new commissioner has been on the job for less than three months, but in banning Sterling from the league for life, fining him $2.5 million (the maximum allowed by the league), and taking steps to force him to sell the team that he’s controlled for 33 years, Silver has made a stirring display of what the NBA might look like under his leadership. For a man whose lack of charisma has long been a punch line among those who followed the league closely enough to watch Silver drone through the second round of the NBA draft each year, his press conference was a deeply moving display of empathy and respect for all those who’ve done far more for the game than Sterling or any other courtside plutocrat ever has.

In a voice shaking with indignation and conviction, Silver name-checked greats like Bill Russell and Magic Johnson alongside lesser-known black pioneers like Earl Lloyd, Chuck Cooper, and Nathaniel “Sweetwater” Clifton. The commissioner came off as a man with a ferocious respect for basketball and, infinitely more importantly, the people who play it. NBA players, Silver’s words and actions affirmed, are not beneficiaries of paternalist largesse, they are not cogs in the addled fantasies of billionaires, they are not “the help.” They are people, and a handful have been working for an employer who would rather their parents and siblings and children avoid his arena on account of the color of their skin. Viewed in this light, any response less strident than the one Silver just made would have been pathologically callous. Barring Donald Sterling from the NBA was a moral imperative.

The scope and severity of Silver’s ruling exceeded expectations. I wasn’t alone in anticipating something like an indefinite suspension followed by rounds of hedgy deliberations and hypothetical sanctions, and as such Silver’s decision comes as a welcome surprise. It’s also a shrewd and savvy maneuver on the commissioner’s part, one that will decisively consolidate his authority going forward and buy him a tremendous amount of goodwill in the league he oversees, most notably among its players. It’s convenient for the NBA, and for Silver, that he’s only been on the job for a few months and so can wash his hands of the league’s indefensible, decades-long inaction with respect to Sterling. As former commissioner David Stern’s right-hand man, Silver certainly played a role in abetting Sterling’s continued ownership of the Clippers. But once he was in charge, he did what needed to be done, and that cannot be minimized.

Indeed, this was a watershed day for the NBA, not simply for the words spoken at the podium but for what Sterling’s banishment means as a symbolic moment in the history of the league. Since the passing of the Lakers’ Jerry Buss last year, Sterling has been the longest-tenured owner in the NBA. He’s also the last link to an unsavory past that the league has long been trying to outrun, the bad old days of Finals games on tape delay, horrendous business deals, fistfights, and drug scandals. When Sterling bought the Clippers in 1981, Bird and Magic had only just begun their pro careers, Michael Jordan was still three years away, and Stern was not yet commissioner. Sterling paid a little more than $12 million for the Clippers; today the team is valued at $575 million. He will soon (but still not soon enough) sell them for a price that will likely exceed that lofty figure.

Sterling was a horrific owner. Peter Keating’s withering 2009 ESPN profile is essential reading for anyone needing a reminder of just how awful his decades of stewardship have been (although at present, few need a reminder of this). In 1984, a mere three years after purchasing the Clippers, Sterling moved the team to Los Angeles from San Diego against the league’s wishes. The NBA fined him $25 million. Sterling then countersued for $100 million, successfully intimidating the league into lowering his fine to $6 million, which he never really even ended up paying (his penalty came out of his share of expansion payments, as opposed to his actual wallet). This more or less set the tenor of his relationship with the NBA. He was an eccentric and wrathful cretin, a constantly looming nuisance whom everyone just sort of left alone.

Which was easy to do, because the Clippers were terrible. In 2000, Sports Illustrated famously dubbed them the worst franchise in the history of sports, a title as ignominious as it was uncontroversial. The Clippers have now made the playoffs in three consecutive seasons, but in the previous 30 they’d appeared in the postseason just four times. In their first 10 seasons under Sterling’s control, they never finished higher than 10th in the Western Conference. Sterling did not care about the performance of his team, and he did not care about its players or its fans. He cared only about his profits, which were massive. After all, he was running an NBA team into the ground by spending as little money as possible while the league was exploding in popularity, thanks largely to the work of the very kinds of people he didn’t want attending his games.

The Clippers’ current success is due in no part to Sterling’s own accomplishments, but rather to one of Stern’s most notorious maneuvers as commissioner. In late 2011, he blocked a proposed trade of perennial all-pro point guard Chris Paul from the league-controlled New Orleans Hornets to the Lakers, then orchestrated Paul’s landing with the Clippers. Last summer, the Clippers uncharacteristically brought in a great coach, Doc Rivers, and once-unthinkable fantasies of championship banners danced in fans’ heads, and maybe even Sterling’s own. Now that the Clippers are finally an elite team, they’ve begun to get the scrutiny they’ve always deserved. Sterling’s appalling history of racism and misogyny had long been on display to anyone who cared enough to look, but few really had. (Rivers claimed he didn’t know about Sterling’s racial transgressions before taking the head coaching job.) The fact that this audio tape exists isn’t shocking, it’s only shocking that it’s taken so long for something like it to surface. Despite Sterling’s banishment, it remains a black eye for the league and all who cover and follow it that it’s taken so long for us to finally care.

But it’s better late than never. The NBA has finally rid itself of the last vestige of its worst self, a vile lizard of a man who profited off others’ talent and success and was stupid enough to mistake it for his own. Who makes the game? Now, the answer is what it always should have been: anyone but Donald Sterling.