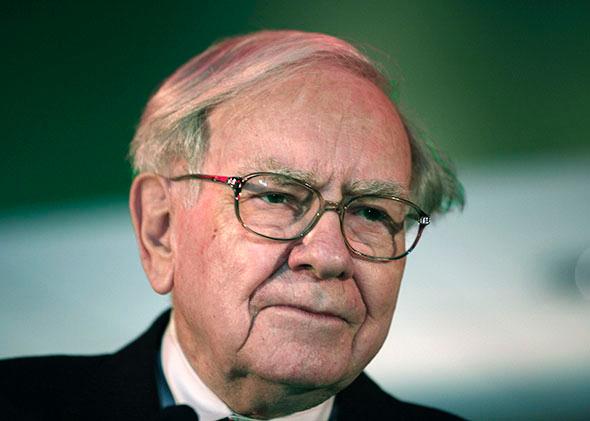

Thanks to Warren Buffett and Quicken Loans, signing up for a shot at $1 billion is as simple as filling out a form on a website.

Just register online for the Billion Dollar Bracket Challenge, make your March Madness picks, and crack open a High Life. If you pick the winners of 63 NCAA Tournament games (you don’t even have to pick the winners from the play-in round!), you’ll haul in the biggest cash prize in world history. All that, and it’s free to enter. How could you lose?

The contest is a master stroke of publicity: Buffett and Quicken have descended on one of the most electric weeks in U.S. sports, slapped their names all over its most addictive fan tradition, and wrapped the whole thing in a $1 billion bow. It’s enough action, cash, and fun to whip you into a drooling frenzy. Which is probably fine with the sponsors, since if the lusty haze were to wear off, people could start doing silly things like running the numbers or reading the fine print. And if you did that, you’d probably notice the following important things about this contest.

1) You will not win.

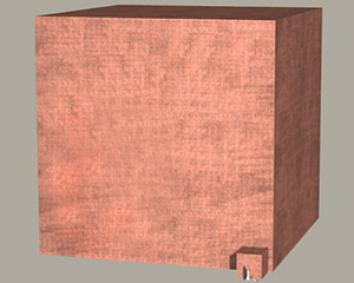

Courtesy of kokogiak.com

There is a chance, but the chance is so vanishingly small that it’s actually more rational to say there’s no chance. As Yahoo and Quicken note in the fine print of their rules page: “odds of winning the Grand Prize are 1:9,223,372,036,854,775,808.” That’s 1 in 9 quintillion and change. See the image to the left for what a mere 1 quintillion pennies would look like (the larger white sliver is the Empire State Building). Another way to think about it: If all 317 million people in the U.S. filled out a bracket at random, you could run the contest for 290 million years, and there’d still be a 99 percent chance that no one had ever won.

Unlike the lottery, basketball isn’t random. Better teams usually beat worse teams. And many people who fill out brackets tend to have at least some basic information in the form of the seedings, historical trends, and player stats.

Jeff Bergen, a math professor at DePaul University, derived a more realistic calculation that takes basketball knowledge into account. If you know the sport pretty well, he concludes, your chances of picking perfectly are more like 1 in 128 billion.

Still not so hot. As Bergen explained, that would mean you’d need to fill out about 90 billion brackets before you even had a 50-50 chance to win.

2) No one will win.

ESPN has been running a large-scale bracket contest for 13 years. Nobody has ever come close to perfection, the sports network’s John Diver told CNN in January. Only one person in the last seven years managed to pick just the first-round winners correctly.

“I don’t want to say it’s impossible,” Diver said, “but it’s basically impossible.”

The giant Powerball and Mega Millions lotteries are set up so that someone has to win eventually. As a given jackpot grows, more people hear about it and buy tickets, and since there’s no limit on the number of tickets sold, the probability that one of them is a winner approaches 100 percent.

Not so here. Buffett and Quicken have capped the number of entries at 15 million, so the odds that there’s a winner stay very, very small. If you use Bergen’s calculation, generously assuming the contest fills up with 15 million basketball experts, then Buffett and Quicken would have to pay the billion only 0.012 percent of the time. That means there’s about a 1 in 8,500 chance that anyone wins, period.

To be fair, Quicken is paying $100,000 to each of the 20 best “imperfect” bracket pickers. But the contest wouldn’t have nearly the marketing pizzazz if it were called the $100,000 to 20 People Bracket Challenge, like it probably should be.

3) In the imaginary case that you’re about to win, Buffett will buy you out.

Buffett told the Los Angeles Times that if someone gets to the Final Four with 60 out of 60 correct, he would probably try to buy them out before they won it all. “I’m not sure Quicken would let me do that,” Buffett told ESPN.com’s Rick Reilly, but then proceeds as if he’s pretty sure he could. “If I offered you $100 million to call off the bet, I bet you’d take it,” he said to Reilly.

That $100 million actually sounds like too much. That L.A. Times piece notes, “Most people would have a very hard time turning down $10 million when there was a chance they could get nothing.” The point here is not that $100 million or $10 million is a bad result: It’s that the $1 billion is a mirage, a hypnotist’s spiral.

All of this makes this a great deal for Buffett. In addition to all the publicity he’s getting, the Oracle of Omaha’s company Berkshire Hathaway is also insuring the payout, with Quicken paying an undisclosed sum to cover the $1 billion if the world were to turn inside out and someone did win. Buying a policy to insure you against a very unlikely outcome wouldn’t cost very much, so whatever Quicken’s paying also reflects Buffett’s lending of his name, image, and credibility to the affair. (Buffett, via Berkshire Hathaway, did not respond to a request for comment on the contest or his role in it.)

4) You get squat, while Quicken gets a real jackpot.

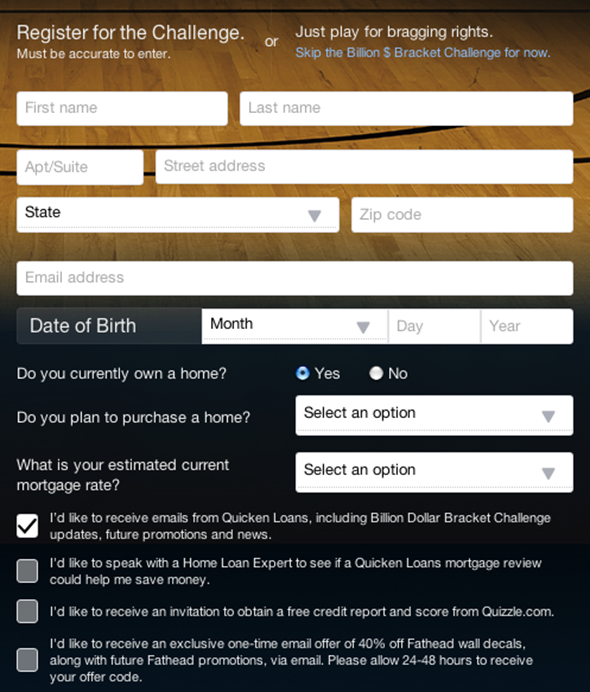

Screenshot via quickenloansbracket.com

To register for the contest, you have to sign up for a Yahoo account—a boon in itself for Yahoo, on whose site the contest is run. Then you’re asked to enter your name, address, email, birthday, and the answers to several questions about your home mortgage situation. All of this information goes to Quicken Loans, the fourth-largest mortgage-lender in the U.S.

It’s no coincidence that this information—where do you live? Do you want to buy a home? What’s your current mortgage rate?—is exactly what you need if you want to sell someone a home loan.

“That is a very rich amount of information, very rich,” says David Lykken, a managing partner at Mortgage Banking Solutions, an Austin, Texas-based consulting firm. “Brilliant—information you can get the consumer to supply for no cost.”

It’s not uncommon for companies like Quicken to pay between $50 and $300 for a single high-quality mortgage lead, Lykken says.

Quicken says the info-gathering is not intended for lead generation. Instead, the company says it’s building a base of relationships with people who may want home loans in the future. “The people that are playing the Billion Dollar Bracket kind of fit our demographic,” says Jay Farner, Quicken’s president and marketing chief. “But for the most part, unless they’ve opted in and said ‘please call me,’ it’s not a mortgage lead for us.”

Whether you want to call it a mortgage lead or not, this is a savvy maneuver. In a mortgage industry that’s going through a big contraction because of rising interest rates, Quicken is getting potential customers to run, panting, to its doorstep. Ka-ching!

After the mortgage crisis, federal policymakers made it more difficult for companies to sell dodgy loans. And to be clear, Quicken doesn’t belong in the same category as firms like Countrywide Financial and Ameriquest, which helped torch the economy with subprime loan sales. But the question remains: What are you really getting when you give your private information to this corporation? No question that it’s a very, very good bet—you’re just on the wrong side of it.