On June 22, 1937, Joe Louis knocked out James Braddock with a right to the jaw to become the world heavyweight champion. At a time when Major League Baseball was still a decade from integration, Louis’ victory in Chicago’s Comiskey Park was a triumph for black America, and for racial progress. “What my father did was enable white America to think of him as an American, not as a black,” Joe Louis Jr. told ESPN in 1999. “By winning, he became white America’s first black hero.”

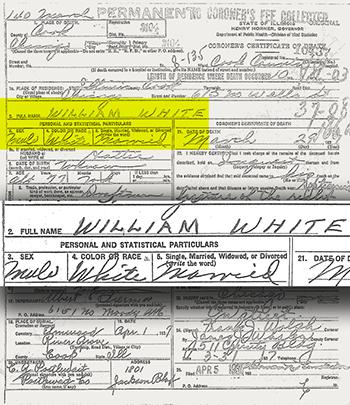

Three months before the fight, another notable moment involving race and sports occurred in the same city: the death of a 76-year-old man named William Edward White, of blood poisoning after a slip on an icy sidewalk and a broken arm. Fifty-eight years earlier, White played a single game for the Providence Grays of baseball’s National League to become, as best as can be determined, the first African-American player in big-league history. Unlike Louis’ knockout, though, White’s death merited no coverage in the local or national press. A clue as to why can be found in cursive handwriting in box No. 4 on White’s death certificate, which is labeled COLOR OR RACE. The box reads: “White.”

Cook County Clerk

William Edward White was born in 1860 to a Georgia businessman and one of his slaves, who herself was of mixed race. That made White, legally, black and a slave. But his death certificate and other information indicate that White spent his adult life passing as a white man. Since the 1879 game was unearthed a decade ago, questions about White’s race have clouded his legacy. If he didn’t want other people to think of him as black, did he actually break the sports world’s most infamous racial barrier? Or is the reality of his racial heritage, and the difficult personal issues it no doubt forced him to confront, enough to qualify him as a pioneer? Should William Edward White be recognized during Black History Month alongside Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson and other groundbreaking African-Americans?

These are complicated questions. Allyson Hobbs, an assistant professor of American history at Stanford, says the practice of “racial passing” in America dates at least to runaway slaves in the 1700s. Slaves, she says, often attempted to pass as white to gain their freedom but then lived out their lives as black. By the Jim Crow era, when William White came of age, the social and economic advantages of living as white—and the disadvantages of living as black—were so profound that people who could successfully pass did so and never looked back.

“People who passed did not want to leave a trace,” says Hobbs, whose book A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life will be published by Harvard University Press in the fall. “They did not want to leave records, they did not want to have anyone find them, to discover that they were passing. It’s very difficult to get a well-rounded image of these people’s lives, and that’s by their design. It’s a hidden history, and it’s one that can be very frustrating because there is often so little data available about these people.”

That’s certainly the case with William Edward White. For years, only a handful of baseball historians had even heard of him, and then only as a name on a list of 19th-century players about whom nothing was known. Then, research by Peter Morris (one of the authors of this article), Bruce Allardice, and other members of the Society for American Baseball Research—as part of an ongoing project to compile biographical information on everyone who has ever played in the majors—revealed White’s baseball and racial story. (The co-author of this article, Stefan Fatsis, reported the findings in the Wall Street Journal in January 2004.) White’s death certificate was obtained in December thanks to research by an Atlanta-area genealogist named T.J. White (no relation), who has looked into the ballplayer’s past, and Robert Sampson, an adjunct history professor at Millikin University in Decatur, Ill.

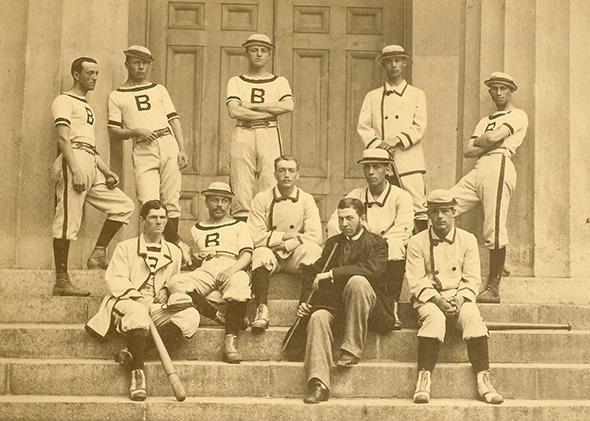

After first baseman “Old Reliable” Joe Start broke a finger, the Providence Grays, who played in the National League between 1878 and 1885, recruited White, an 18-year-old freshman at Brown University, to fill in. On June 21, 1879, White got a hit, scored a run, stole two bases, and fielded 12 chances flawlessly in a 5–3 win over the visiting Cleveland Blues. The Providence Morning Star reported that White’s collegiate teammates “howled with delight” from the stands. The Providence Journal said White “played first base in fine style” and “has been engaged to cover first” in an upcoming series versus Boston.

But White didn’t play for the Grays against Boston—outfielder and future Hall of Famer “Orator Jim” O’Rourke took over at first—or ever again, or for any other big-league team. Did the Grays decide they could make do without an extra player? Did the veterans balk at including a college student in the lineup? Or was White not invited to return because his mixed-race status became known or was suspected?

We don’t know. Here’s what we do know: White’s father, Andrew Jackson White, was a well-off merchant and railroad president in Milner, Ga., who at one time owned 70 slaves. One of them was named Hannah. A.J. White and Hannah White had three children, and records indicate that they lived as a family. In his will, A.J. White left the balance of his estate to the children. It wasn’t uncommon for black or mixed-race children to be sent north to be educated, and William attended a Quaker boarding school in Providence before matriculating at Brown. Records at Brown list A.J. White as William’s father. They also say that William White was white.

White played baseball at Brown in in 1879 and 1880 but, for unknown reasons, left school without graduating. He moved to Chicago, found work as a bookkeeper and later a draftsman, and married a white woman, Hattie Hill. They had three daughters. But White separated from the family sometime in the 1910s, and his whereabouts for the next few years are unknown. White reappears in a 1923 Chicago city directory, and he may have fallen on hard times: His address is McQuinn’s Peerless Hotel, a 25-cents-a-night flophouse.

White’s death certificate is signed by a son-in-law, Albert Bierma. It lists White’s wife’s name but not his birthplace or the names of his parents. That could indicate that family members didn’t know much about White’s background, or that they just didn’t disclose it.

In the decade since we reported on his 1879 game, White’s name has entered the conversation about early black baseball players. In his book Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game, Major League Baseball official historian John Thorn writes that the accepted history of the first African-American big-leaguers had to be “amended” because of White. (Prior to the discovery of White’s brief playing career, Moses Fleetwood Walker, who played 42 games for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association in 1884, and Walker’s brother, Weldy, had been credited as the major leagues’ first African-American players.) White also gets a brief mention in a timeline in a Baseball Hall of Fame exhibit, “Pride and Passion: The African-American Baseball Experience.”

Not everyone thinks that White should be considered the first black major leaguer. In a history of Brown University baseball published in 2012, Rick Harris writes that White wasn’t even “the first black man to play on a Brown University baseball team because he was biracial and chose to identify himself as white.” Similarly, baseball historian John Husman holds that White is the first black big-leaguer only by “the retroactive application of genetic rules.” In Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century, Husman writes, “He played baseball and lived his life as a white man. If White, who was also of white blood, said he was white and he was not challenged, he was white in his time and circumstances.”

But racial identity in late 19th- and early 20th-century America wasn’t that simple. When he took advantage of the opportunity to be seen as a white man, White didn’t cease being part black. Hobbs, the Stanford historian, notes that it’s impossible to know how White viewed his own racial makeup. He may have genuinely considered himself to be white. He may have been conflicted about passing—and worried daily that he would be discovered. Or he may have let others—the registrar at Brown, federal census takers, his future wife—make the reasonable assumption, given his economic means and his light skin color, that he was white. Once a document said he was white, William White could be white forever.

“It’s hard for us to know how someone like William White saw himself,” says Hobbs. “It’s a very personal question. And this is where the official documentation doesn’t help. The fact that he is white on a death certificate or attending Brown and playing this game in the major leagues, that doesn’t give us insight into his own ideas of his racial identity. It tells us what our society believed him to be but it doesn’t tell us what he believed himself to be.”

It’s conceivable that, when he headed north from Georgia, White was told by his father that from that moment forward he should identify himself as white. That theory is backed by T.J. White, the genealogist, who while researching White family history in 1988 interviewed a member of the Whites’ church in Georgia who remembered elderly “Aunt Hannah,” William White’s mother. According to the genealogist’s notes, the parishioner, Sally Woodall Domingos, told him the White children “were trying to pass as whites up North, where no one knew of their mulatto mother.” She also told him that William White never returned to visit.

White appears to have succeeded in passing. He is listed as white in the 1880, 1900, and 1910 federal censuses. (The 1890 records were damaged in a fire and later destroyed.) The only possible discrepancy is in the 1920 census. White at that time would have been 60 and separated from his wife and daughters. The census lists a 60-year-old William White born in Georgia and living just outside Chicago. This William White described himself as a widower, a laborer, and black—three details that don’t match the former ballplayer’s previous census entries. While it’s possible that White’s origins had been discovered and he decided to alter his racial identity, that doesn’t seem likely after 40 years of living as a white man. White couldn’t be located in the 1930 census.

Until she was contacted last month, White’s only grandchild, Lois De Angelis, said her family had been unaware of White’s role in baseball history, and of his racial background. De Angelis, who is 74 years old and lives in Grayslake, Ill., said she knew that her grandfather worked as an artist and had been published in the Saturday Evening Post or another magazine, and that he was separated from her grandmother, who worked as a secretary for Sears. Beyond that, De Angelis said she knew nothing about William Edward White.

White’s wife, Hattie, lived until 1970. De Angelis doubted that Hattie would have known White was one-quarter black, at least before they were married. “My grandmother was very prudish, very English,” she said. Neither Hattie nor De Angelis’ mother, Vera, ever mentioned why Hattie and White had separated, De Angelis said. Perhaps, she speculated, White left the household because Hattie discovered his racial history. “That’s funny when I think of my grandmother,” De Angelis said. “She would die if she knew it.”

So where does that leave William Edward White? Baseball pioneer or baseball footnote? When he trotted out to first base at Messer Street Grounds in Providence, White may have been the only person who knew that a black man was playing in the big leagues. And even that assumes White thought about the fact that he was black, or even partly black. In the racially bifurcated America of the times, “you were black or you were white,” Hobbs says. If no one else knew—if society couldn’t respond and react—it’s reasonable to question whether White should be recognized as the first African-American major-leaguer.

Or maybe that’s a distinction without a difference. American history and its precision-loving subset of baseball history are filled with the sort of ambiguity that complicates the search for convenient, ironclad “firsts.” This much is indisputable: On June 21, 1879, a man born a slave in Georgia played in a major-league baseball game. A black man named White played for the Grays. Factually and figuratively, that seems right. And it seems worth celebrating.