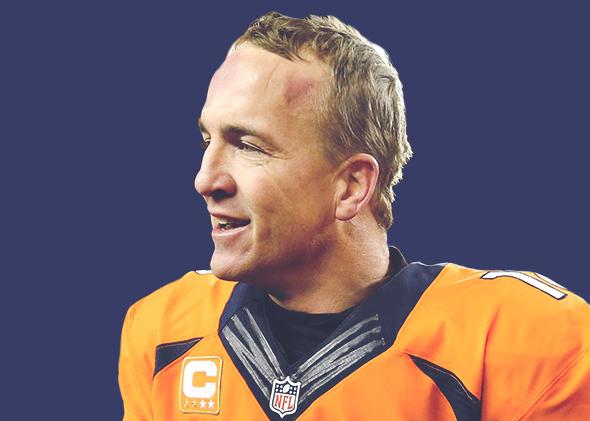

On Sunday afternoon, Denver Broncos quarterback Peyton Manning—an incredible, historically great football player—will take to his mile-high field to chase away demons, with a chorus of angels behind him. Having bounced back from a 2012 season that ended in too-familiar heartbreak, Manning now finds himself on the precipice of an unprecedented fifth Most Valuable Player award (no one else has more than three), and two wins away from an elusive second Super Bowl victory. Regardless of what happens this weekend, some day in the not-too-distant future Manning will retire with nearly every significant passing mark in the NFL record book, and many more insignificant ones.

Manning is the most beloved player in his sport. Last month Sports Illustrated bestowed its Sportsman of the Year honor on Peyton, with Lee Jenkins’ cover story opening with the vaguely messianic device of tracking down teenagers named after Manning during his time at the University of Tennessee. In an era with a neurotically insatiable appetite for building up heroes, tearing them down, then scolding each other for building them up in the first place, Manning is almost talismanic. The affection he inspires resists its own contradictions. We love him because he’s a football superhero; we love him because he’s just like us. We love him because he’s a preternaturally gifted genius; we love him because he outworks all those more gifted than he is. When, after last week’s win against the San Diego Chargers, Manning expressed a hankering for a Bud Light, video of the star with the nine-figure bank account asking for a $2 brew instantly went viral, as if it bespoke some primal authenticity rather than just a godawful taste in beer.

Manning is the rare athlete who reaps all of sports-talkdom’s positive clichés while remaining curiously immune to its negative ones. At the risk of being struck by lightning (or worse—I live in Colorado), there are alternate stories one could tell of Peyton Manning: that he’s a regular-season phenom whose vaunted decision-making flees him when the lights are brightest; that he’s occasionally behaved as a coddled star, prone to deflect blame onto teammates and coaches; that he’s disproportionately benefitted from stat-padding offenses and convenient rule changes.

I’m not saying that we should tell these stories, just that we could and we don’t. And we also pat ourselves on the back for not doing so. “He owns only one Super Bowl trophy, which constitutes some kind of moral failing in this all-or-nothing age, but he remains the reigning champion of the everyday,” swooned SI in its Sportsman of the Year profile, the sentence equivalent of a garbage-time touchdown. “For many, this will be a referendum on Manning’s place in the pantheon,” declared Peter King earlier this week. “For at least three hours Sunday, I hope America will stop judging what it will think of Manning in 2033 to enjoy a great football game.” Yes, if only we might avoid unfairly judging a player based on a single game.

Hectoring Peyton Manning for not being able to “get it done” is easily as meaningless as declaring him “reigning champion of the everyday.” It’s the contortions toward the latter, though, that betray a love affair that’s become desperately intense. The sheer idea of Peyton Manning is unfathomably important to the National Football League, to those who work for it and task themselves with protecting it.

The NFL has had, by most conceivable measures, a very bad year. The concussion crisis that the league attempted to quiet with a well-publicized settlement back in August has not been remotely quieted, as former stars continue to come forward with concerns over chronic traumatic encephalopathy and mental health. Scrutiny has only intensified in the wake of Frontline’s shattering League of Denial documentary and the NFL’s clumsy attempts to brush the film and its findings away.

In all of this Manning has emerged as an unsullied exemplar of gridiron glory, a paragon who makes football’s ugliness disappear in a hail of Omahas. In a season in which serious injuries have ravaged the league to distracting extremes, Manning is The Recoverer, the 37-year-old who battled back from spinal fusion surgery to once again stand atop the league. Lost in this week’s hype was the news that Manning will soon undergo another neck exam, the results of which may yet prompt thoughts of retirement.

Professional football has a way of chopping down athletic transcendence. Earl Campbell spent his career ramming through defenders. Now, he struggles to walk—and he’s better off than many of his contemporaries. In a sport that’s becoming synonymous with brain damage and physiological decay, Manning’s career arc presents an appealing alternative. In the golden years of his long career, the noodle-armed quarterback set league records for passing touchdowns and passing yards. He is The Intellect, a figure whose success is not so much a triumph of supreme athletic prowess, but of unmatched football acumen.

Manning’s status as the NFL’s white knight also allows the league to cloak itself in an aspirationalism that plays well with customers who wish the people destroying their minds and bodies on their television screens were a little more polite and well-behaved. The Mannings—father Archie, brother Eli, and Peyton himself—are now comfortably enshrined as America’s First Family of Football, an affluent, educated, two-parent, CTE-free household that’s something of an idealized cradle for NFL stardom. In reality, it’s the ridiculously glaring exception.

That exception will only become more exceptional. In a moment when the question of “would you let your son play football?” has become a treacherously loaded one—posed incessantly to players, coaches, even the president of the United States—the Manning family carries tremendous symbolic power for a league that must bristle every time that question is asked. The horror at the heart of the future of football—one that’s already begun to reveal itself, and will only continue to—is that for as long as the sport’s popularity endures against the harsh light of what we’re coming to learn about it, the NFL will increasingly come to rely on a starkly class-based labor force. Football will be something that poor kids will play but rich kids won’t, because their parents won’t let them, even as the rich kids and their parents will continue to watch.

Manning is both one of the greatest players of all time and the fantasy barricading against this encroaching reality. When Roger Goodell confidently declares that he would “absolutely” let his nonexistent son play football, he can clear his throat and point to Peyton and Eli Manning as justification for his nonexistent decision. It seemed fitting that only a month after ESPN announced that it was cutting its ties with Frontline over League of Denial (a decision rumored to have been made at the NFL’s aggressive behest), the network aired the documentary The Book of Manning, a film described by ESPN as “a father-and-son story written into the pages of football folklore.” Whatever facts unfold in Denver on Sunday, rest assured that the NFL will do its best to keep printing the legend.