This piece has been adapted from David Shoemaker’s new book The Squared Circle: Life, Death, and Professional Wrestling.

On Aug. 1, 1953, legendary Chicago Cubs announcer Jack Brickhouse was working his second job: vouching for professional wrestling. In television’s infancy in the early 1950s, the DuMont Network turned to Fred Kohler’s Chicago wrestling outfit to fill time. It was easier to film than any other sport, they were already making shows for the local station, and, well, wrestling wasn’t quite as commonly ridiculed as it is today. What questions there were about the sport’s validity were assuaged by the involvement of reputable newsmen like Brickhouse. On this night, the broadcaster would face a difficult task. He had to interview the world’s second-most-infamous Nazi.

“I am going to win ze title and take it back to Germany vere it belongs,” said Hans Schmidt. “I vill never give an American a crack at it.”

But isn’t that turning your back on the USA, the country that’s been so good to you? Brickhouse begged.

“Germany is good to me.”

Brickhouse bristled and pointed out that German immigrants in America resented him because he gave them a bad reputation.

“I don’t care about zem. Let zem learn the hard vay like I did.”

But didn’t Schmidt have any respect for good sportsmanship?

“People who teach sportsmanship to zer children are crazy. The only answer is to vin at any cost.”

But didn’t he care about the fans at all?

“I don’t like ze fans. As a matter of fact, I hate zem.”

At this point, Brickhouse snatched the mic away—this Schmidt was not the sort of athlete he was accustomed to. “As far as I’m concerned, this interview is over,” Brickhouse said.

There had been wrestling villains before Hans Schmidt, but never one quite as heelish as this. The bad guys of earlier eras were mostly painted in the subtle hues of receding hairlines and roughneck mannerisms. There had been foreign nationals, too—Stanislaus Zbyszko and Georg Hackenschmidt were both champions who tended to get booed by American crowds. But never had a wrestler so played up his otherness, and so inflamed geopolitical biases. Hans Schmidt was hated. Really, truly hated.

* * *

According to Jack Brickhouse, the DuMont Network got 5,000 letters and telegrams denouncing the Teuton Terror, as Schmidt was known. If LeBron James or Tom Brady had denounced sportsmanship so, if they had the temerity to growl at the fans—the fans—their careers would be in jeopardy. For Hans Schmidt, though, this was a star-making moment.

In the decade following World War II, Schmidt would challenge for the World Heavyweight Championship numerous times, including a string of matches against the iconic Lou Thesz—with whom he was beefing at the time of that interview—as well as champs Pat O’Connor, “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers, Lou Thesz again (during his ill-conceived second reign), Gene Kiniski, and Jack Brisco.

Though he would hold lesser championships throughout his career, Schmidt lost every one of those heavyweight title bids. Presumably this helped in some small way to soothe the collective memory of the American public. But the ecstasy of his losses was only possible because of the ire his personality created, and the wounds his thick German accent reopened. After that fateful interview with Brickhouse, a Mrs. Naomi T. Rogers of Syracuse vented her outrage to her local paper. “I nearly smashed our [TV] set,” she wrote. “I am urging every one of you as American citizens to please write to our President Eisenhower and demand the deportation of this chap Hans Schmidt from our country immediately. There is enough corruption without importing it.”

Alas, if they were going to deport Schmidt, it wouldn’t be to Germany. Hans Schmidt was really Guy Larose, a man from Joliet, Quebec, who had a fair bit of success wrestling in the United States under his own name. But while passing through Boston in 1951, he caught the eye of a local wrestling promoter named Paul Bowser who thought Larose’s tall frame, geometric features, and receding hairline made him the perfect Nazi. “It was hard with a French name like that,” Schmidt said later in life. “When you got to the States, people were making jokes. … [Bowser] was German and he told me I looked like a German. That’s when he gave me that name.”

Bowser was one of the first ringmasters of the farcical side of the pro wrestling world. In 1928 he propelled a young former NFL player named Gus Sonnenburg to national stardom when he brought his “flying tackle” from the gridiron to the ring, taking pro wrestling into the air—and into blatant choreography—for the first time. In the 1930s, desperate for an Irish megastar to draw the local immigrants into the arenas, he positioned Danno O’Mahoney as his champion despite Danno’s obvious inability to wrestle. In the late ’30s, he imported Maurice Tillet—the French Angel, a grotesque, ogre-faced man whom Shrek was modeled after—to America. Bowser wasn’t a stickler for tradition, nor was he afraid to upend convention to make fans swoon. Schmidt was the last big star he made before he retired, and what a creation he was.

The origin of Hans Schmidt’s nom de ring is unclear, though it was possibly inspired by the Buchenwald defendant of the same name—the attendant to concentration camp head Hermann Pister. The name was also in the national memory from the famed trial of a Catholic priest named Hans Schmidt who murdered and dismembered a girl named Anna Aumueller, attempted to make counterfeit money, and intended to murder even more people as a means to defraud insurance companies. (Hans Schmidt was also the name of a fairly significant symphony conductor, though it’s safe to say that that one held no bearing on the Teuton Terror’s creation.)

Schmidt flouted the rules of the squared circle, brutally kicking his opponents—a tendency that earned him the locker room nickname “Footsie”—and tossing them from the ring and onto the floor. He was touted as having spent two years in a French POW camp during the war—the grist, one presumes, for his toughness and anger issues. He often attacked referees, cheated brazenly, and remained seated during the national anthem. All of these traits would become staples of villainy in the wrestling world, but they were new, and genuinely galling, in Schmidt’s day. He didn’t need to carry a Nazi flag or goosestep to the ring. This was a subtler time, and Schmidt’s assault on morality and good sportsmanship was, to the midcentury sports world, as devastating as the backbreaker with which he ended his matches.

Schmidt emerged from a period in which wrestling was largely based on immigrant nationalism. Greeks, for instance, were good guys in front of Greek audiences and villains elsewhere, and wrestlers would often change their land of origin from night to night to play up to a specific crowd. Schmidt played a role in this phenomenon, but he evolved into something much larger—a representation of pure evil. As New York promoter Al Mayer put it to A.J. Liebling in a 1954 New Yorker piece: “Nationalism is dead. That was neighborhood stuff. On television, it would mean nothing, because you wouldn’t know which nationality to make the villain. What the new wrestling public is interested in is villainy as villainy, virtue as virtue.”

* * *

On Jan. 16, 1953, six months before that fateful Brickhouse interview, Schmidt fought Lou Thesz, who would go on to be a legendary champion of the sport. The cover of that month’s issue of the magazine Wrestling As You Like It had a photo of Schmidt advancing, a menacing look on his face. The understated cover line: “Hans Schmidt—He Can Annoy You.”

The accompanying article has the same purple earnestness of a boxing magazine of the day, but there are hints at the menacing nature of “the unruly German”: “The German heavyweight may be unethical but it must be admitted that there is plenty of turmoil when he wrestles. … If he defeats Thesz he will be one of the most colorful heavyweights in the history of the mat sport.” (Though most wrestling magazines were reluctant to use the term “Nazi,” the New Yorker’s Liebling referred to Schmidt straightforwardly as “a horrid Nazi villain.”)

Jack Dempsey was imported as special guest referee to keep Schmidt’s rule-breaking tendencies in check. Retired boxers would often work as wrestling refs—like Brickhouse and his ilk, the boxers traded sports legitimacy for cash. “Legitimacy” should be used loosely, as the boxers’ typical role would be to slug the villain (or feign to) when he broke one too many rules, allowing the hero to win. Dempsey’s role in that brawl wasn’t central—it ended with the two “huggers” brawling into the crowd—but in September of the following year, Schmidt lost (separately) to Vern Gagne in Denver and Antonino “Argentine” Rocca in Chicago. The former match ended when two jabs from referee Joe Louis helped fell the German; in the latter, Louis only needed to threaten the punch.

After that the Gagne match, Schmidt was suspended by the Colorado State Athletic Commission for 60 days. Outrageous acts, followed by routine spankings from state athletic commissions, were a staple of the German’s wrestling reign. In 1953 Chicago’s Arena-Auditorium Board threatened to cancel future wrestling shows after Schmidt hit Gagne (a frequent adversary, plainly) over the head with a chair and fans overwhelmed security and rioted. Later that year, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported that Schmidt had again “been ordered to appear at the Illinois Athletic Commission’s next meeting on Monday to show cause why he shouldn’t be suspended for violation of rules.” This time, though, the commission had a new twist: Schmidt had “been identifying himself as a German citizen, whereas he is a French Canadian. The commission has ordered him to refrain from doing it in the future.” Thereafter, Schmidt stopped claiming Germany as his home, though he didn’t switch to Quebec. He opted instead for his new home: Chicago, Ill. The enemy had arrived, and he was us.

These sports commissions played the same role as reputable men like Brickhouse and Louis. They happily took promoters’ money in exchange for “regulating” wrestling matches just as they would any other sport—thus the threat of suspensions to a bad guy like Schmidt.

Schmidt reveled in the infamy, and his transgressions only multiplied. In May 1954 Gagne again beat Schmidt—“one of the mat’s more prosperous villains,” the local paper called him—but chaos broke out toward the start of the match when “Schmidt, after knocking Gagne out of the ring four times, leaped from the ring himself and resumed the attack. Several score of ringside spectators swarmed to the rescue, pummeling Schmidt with pocketbooks and hands. Order was restored by the special Hans Schmidt squad of 12 policemen, who bivouac in the Auditorium when the villain appears there.”

Many such incidents followed. A 1956 piece in the Milwaukee Sentinel recounts a near-riot, with the implication that the whole thing was a setup by the promoter: “But when Schmidt, who spun Gagne from the ring, wouldn’t allow him to return, the ‘chorus’ was brought to fore. The lawmen ran hither and yon, but in vain. The spokesman shoved the announcer, the announcer yelled to the time-keeper, the time-keeper tussled with the spokesman, the damsel argued with the other lawman and Schmidt tasted a stiff punch to the chops by a fan that sent him scurrying for cover.”

Following a bout between Schmidt and Tarzan Kowalski, that same Milwaukee paper called for his ban from Wisconsin:

The alleged wrestling match … has been a matter of history for more than a week, but the memory lingers on. Letters of protest are still coming in. … Their underlying theme: “We want no more of Schmidt. He should be barred forever.” As one disgusted spectator put it: “I realize there must be some dirty work in wrestling to make it interesting, but when one man tries to choke another with a microphone cord, as Schmidt did, it’s time to kick him out as other states have done. He’s a dangerous person. I wonder why the immigration service ever let him into our country.” Everybody must realize by now that the lifeblood of modern wrestling is the knack of coming up with something new and different. Yet it’s quite apparent there’s a limit to how much dirtiness, real or phony, the customers will take. So let that be the end of Schmidt-ism. It isn’t even good entertainment.

The distaste for Schmidt wasn’t limited to op-eds and arena riots. He was constantly tormented in public, cursed at and slugged everywhere he went, and in the arena on the way down the aisle, he was regularly stabbed with hat pins and burnt with lighters. According to former wrestling manager Percival Friend, Schmidt had three cars destroyed on separate nights in Canada before the Royal Canadian Mounted Police could contain rioting fans. In Chicago the police sometimes drove him to the arena themselves after fans took to throwing bricks at his car. Friend says that on nights when Schmidt was particularly nasty, they’d try to set his car on fire. All of these were indelible signs of success.

* * *

Of course, not all the reports of the Terror were so, well, terrifying. The Ring magazine ran a blurb in October 1952 about Schmidt’s softer side: “Hans Schmidt, currently top man of the villains operating in Milwaukee, is reported by his wife to be a sheep in wolf’s clothing. The 27-year-old father of a 21-month-old son tiptoes around the house so as not to disturb the baby. A far cry from the use he makes of his legs in the ring.”

“Outing” Schmidt became a cottage industry for snarks in the press. When Roger O’Gara, a writer for the Berkshire (County, Mass.) Eagle, recognized the faux-German Canadian from his days wrestling in Massachusetts, he referred to him in print as “Larose Schmidt.” (Brickhouse reportedly reamed him out for the transgression—and the commuted insult to his own sportscasting integrity. O’Gara later referred to him in a column as “Jack Brickhead.”) Liebling too wrote of Schmidt as “a horrid Nazi villain, libelously averred by a number of competitors to be a French Canadian.”

In response to such infringements on wrestling’s neverending morality play, Murray Olderman wrote compellingly:

Why the sudden rush of squatters’ rights among the periodicals? Primarily, you’ve got to credit the post-war success of the grappling game because without success there’d be nothing to knock. … Who would deny a pacifistic grandma a night off from her knitting needle to release her paranoia with a hail of invective directed at villainous Hans Schmidt? Or, on a particularly uninhibited night, clout him over the head with a folding chair? At 100 grand a year, Hans isn’t kicking.

Why question success? Nazism hardly mattered. The political ethos in play was capitalism. Outrage sells: At his height, according to wrestling historian Dave Meltzer, Schmidt was one of the world’s highest-paid athletes. In 1954 he was called “probably the greatest drawing card in the past decade in the mat game.” In October 1955, the Wisconsin Telegraph-Herald got to the heart of it, writing that Schmidt, “the wrestling badman, may not have many rooters when he is in the ring, but the fans certainly want to see him.”

Back to that interview with Brickhouse. An editorial ran shortly thereafter in the Oneonta (N.Y.) Star, channeling the nation’s outrage:

Sportsmanship is something Americans are taught early in life. It’s sort of a code of ethics with us. But to Hans Schmidt, the German wrestler in this country for five years, sportsmanship is strictly for the birds. … We hope that millions of Americans who also came up the hard way will boycott Schmidt’s matches in the future and wish him bon voyage to his native land without the championship. This country has no place for a sports figure who refuses to recognize the code which made this country great.

This bold stand was followed on that same page by an editorial applauding right-of-way rules at intersections, a call for blood donations for military men, and a sublime op-ed titled “Milk, the Magnificent.” This was the America into which Hans Schmidt had stomped. His chief foil was never his in-ring opponents. It was the forces of mutual respect, of charity, of a wholesome glass of milk. He stood athwart these forces and challenged an entire country. In the process, he remade wrestling—and villainy—as we know it.

* * *

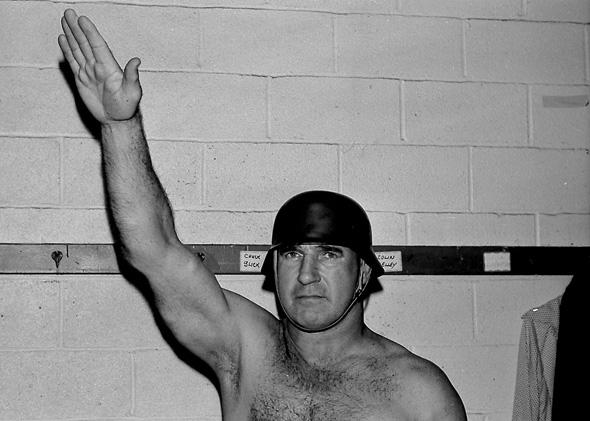

By the ’60s, Schmidt’s act had become old-fashioned, if not stale. He took to wearing a World War II-era German military helmet to the ring, keeping up with more outré and provocative foreigners like Karl Von Hess and Ludwig Von Krupp. Eventually, though, longevity had earned some fans’ respect. He played the foil on some cards, and the begrudging hero on others, usually tag-teaming with former foes like Gagne to vanquish even more diabolical foes like the Volkoff brothers. The world changes, and suddenly Germany isn’t as bad as those evil commies from the USSR.

Schmidt’s wily dominance was, in the end, a testament to a suspiciously American work ethic. He was proud to have made it into the business at all—after all, most of the guys who sought a career in the ring ran for the gym exit after their first day of training, when old-timers would do their best to exhibit the realness of the craft to the wannabes. “Most of the boys would just give up and go get regular jobs. I stuck with it and began to face some of the big names in the business,” he told the Gadsden (Ala.) Times in 1969. “The young punks coming up today are all fakes.”

His crypto-patriotism didn’t end there. The Gadsden Times noted that he had made $1 million over his career: “At one time he was making so much money the government was taking 41 per cent of it, and another time he remembers sitting down and writing a check for $17,000 which he owed to the IRS on one year’s earnings.” The last living Nazi terror had found his toughest opponent: the United States tax code. “I gave the government an awful lot,” he said, “but I made my share, too.”

This piece has been adapted from David Shoemaker’s new book The Squared Circle: Life, Death, and Professional Wrestling.