This weekend I bought 3,000 baseball cards. They cost $30. That’s because nobody wants baseball cards anymore; the industry has shrunk to one-seventh of its peak size in the last 20 years. Baseball, too, has shrunk. Once America’s most popular sport, it’s now a distant second to the NFL, barely ahead of college football in terms of primary adherents. The age of baseball supremacy is over.

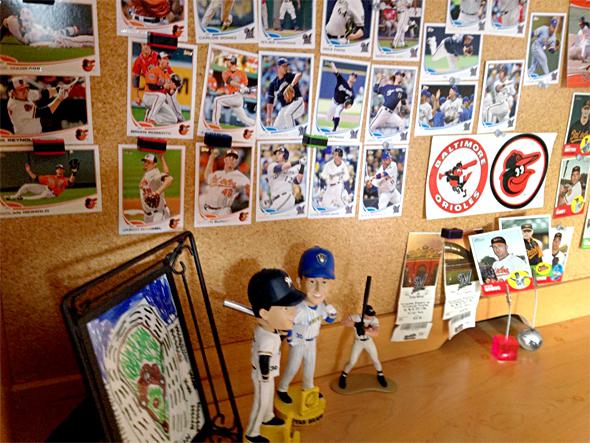

But not in my house. This is what my son’s desk looks like:

Photo courtesy Jordan Ellenberg

My son is 8, and he just finished his first season of Little League. Before he goes to bed each night he needs an update on the scores in the playoff games. And when he gets up in the morning the first thing he asks is how they ended. He can tell you everything you’d want to know, and actually somewhat more, about beloved Brewers like Carlos Gomez, Caleb Gindl, and Aramis Ramirez, whose jersey he wears to school as soon as it’s clean, once a week, summer and winter.

If baseball is antique, boring, and doomed, why does my kid like it so much?

One reason: It’s a kid’s game. The old story of Abner Doubleday writing down the rules of baseball in Cooperstown, N.Y., was debunked years ago. John Thorn’s magisterial 2011 book Baseball in the Garden of Eden tells a more historically grounded story. I used to make fun of Brooklyn hipsters who played kickball, but the truth is that the sport exists today thanks to the early-19th-century version of those hipsters, office workers who thought it would be a kick for grown-ups to play a popular children’s game, and to bet on the outcome for good measure.

So baseball started out with the benefit of the evolutionary honing that all informal playground games do. On top of that, it’s had almost two centuries to smooth down its rough spots as a formalized pursuit. No wonder it’s perfect. Baseball is to sports as ketchup is to condiments: something that doesn’t change much, not because of stuffy conservatism, but because almost any change would make it worse. It’s amazing, how effective the lure of baseball still is, how fast it grabs you. My son, before age 7, was willing to watch any sporting event with me, in a distracted, OK-daddy-is-there-going-to-be-ice-cream-at-this-thing fashion. And then, suddenly, baseball kicked in. He saw how it worked and he was hooked.

Some people find baseball boring, yes. But some people find ketchup boring. Those people can keep their jalapeño mustard and their March Madness.

But what about PEDs? What kind of terrible lessons is my kid learning from a sport whose biggest stars, like Milwaukee’s Ryan Braun, are failing drug tests and getting suspended, or, maybe worse, failing drug tests and getting off on technicalities?

Here’s the thing about Ryan Braun. Kids in Wisconsin love Ryan Braun. He is undisgraced here. I see a kid in a Ryan Braun shirt every other day. As you can see in the photo above, my son has two Ryan Braun bobbleheads on his desk. Kids are smart; they understand what a rule is, that when you break a rule you get punished, and then after the punishment things go back to normal. And they understand baseball much better than scoldy sportswriters do. You cheer for the guys on your team because they’re on your team, not because you can assign them roles in whatever anxious moral drama keeps you up at night. Baseball isn’t a metaphor for the decline of society, or for our pastoral heritage, or for the idea of fair play. It isn’t a side you can take in a culture war. It is itself, and only itself. And it definitely isn’t here to teach us lessons.

I tried to make my son into an Orioles fan, like me. But the day at Miller Park he saw Carlos Gomez steal second, then third, then break for home, scoring on a wild pitch, like he was playing Atari baseball against a team of hapless 8-bit defenders, he became a Brewers fan for life. (To be precise, he describes himself as 70 percent Brewers, 30 percent Orioles.) We get along fine, in our mixed household. The inconsistency of our rooting interests doesn’t bother him. If there is a lesson baseball can offer us, it’s one about our deepest commitments; that they’re arbitrary, and contingent, but we’re no less committed to them for that. If I’d been born in New York, I might have been a Yankees fan, but luckily for me, I was born in Maryland, so I’m not. Jerry Seinfeld once remarked that baseball fandom, in the age of free agency, amounted to rooting for laundry. That’s not an insult to the game, as Seinfeld, a giant Mets fan, surely understood; it’s a testament to its deepest strength. My son’s love for the Brewers, like mine for the Orioles, is a love with no reason and no justification. True love, in other words.