In the first game ever played in a professional baseball league, the first player to get a base hit was James “Deacon” White. He went on to play for the next 20 years or so, well into his 40s. More than one historian has called him the greatest of the bare-handed catchers. It was not until the late 1880s, after Deacon White had caught his final major-league game, that the catcher’s mitt came into popular use.

This weekend, more than 70 years after his death at 91, he will be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. White is the only man who’s being inducted as a player in this year’s class. No living players, including the supposedly drug-tainted Roger Clemens and Barry Bonds, garnered enough votes. Conveniently, the long-dead White is above reproach. He retired in the 1890s. Few have ever heard of him.

I am not a baseball fan. I have little interest in sports of any kind. But I do know about James “Deacon” White. He is my great-grandfather. I am named after him by way of my Uncle Jim Watkins, Deacon’s first grandchild.

Deacon was, above all else, a fire and brimstone Christian of the first order, a Jonathan Edwards, sinners-in-the-hands-of-an-angry-God Puritan. He very much believed that the world is flat, based on the Biblical passage about how Jesus “will send the angels out to the four corners of the earth to gather God’s chosen people from one end of the world to the other.” He did not drink, smoke, curse, gamble, or take performance-enhancing drugs of any kind, as far as anyone knows.

“No one ever yet heard Deacon White say dammit,” reported the Detroit Free Press in May 1886, “no one ever saw him spike or trample upon an opponent; no one ever saw him hurl his bat towards the bench when he struck out; no one ever heard him wish the umpire were where the wicked never cease from troubling and the weary never give us a rest. And think of it! Nineteen years of provocation! Will anybody deny that Deacon White is a great and good man, as well as a first-class ball player.” In 1878, the Indianapolis Journal reported that an umpire had gone so far as consulting with Deacon before decreeing that a base runner was out. When the opponent complained, the ump replied that when “White says a thing is so it is so, and that is the end of it.”

He was not a deacon as such, but taught Sunday school in churches that belonged to a small, fundamentalist denomination, the Advent Christian Church. Charles H. Porter, the one-time president of the National Association’s Boston ball club, told the New York Sun that Deacon received his nickname in 1873, the year he “became church struck.” Porter described meeting White in Corning, N.Y., and trying to convince him to play for Boston. “I had never seen Jim, but I had not been long in the town before I met a clerical-looking man, with a tall hat. He had a pair of the hardest-looking hands I ever saw, and one finger was badly smashed. I had decided that he was the man I was after, and sure enough it was Jim.”

The ballplayer was born in Caton, N.Y., near Elmira, in 1847. The family lore, also attested to in an interview with the Sporting News, is that he learned to play baseball from local veterans of the Civil War. He would have been in his late teens at the end of the war. As a little boy, I used to imagine him peering through the trees at a lost platoon of war-scarred former soldiers playing ball in the mist, like some outtake from a 19th-century Field of Dreams. In those days, Grandpa White was gazing on the dawn of the national pastime.

The farm boy could hit the ball. And he began to play the game more in his scant spare time. Pickup games in fallow pastures were the norm. Amateur leagues formed and afternoon games were played in front of makeshift backstops. The hard-playing White began to stand out as a leader. Between games and chores he found the time, as young men will, to court a little dark-haired girl named Alice who belonged to his church.

They were deeply in love. But the girl’s parents did not share their daughter’s affection for White. Yes, he was a teetotaling, church-going, scripture-quoting follower of the Lord. But he was still a ballplayer. And ballplayers were not coveted as potential sons-in-law in 1867, certainly not by respectable people.

So Jim White moved on to Cleveland and became the starting catcher for Forest City, a semi-pro team. When Forest City joined with other Midwest and Eastern teams to form the National Association of Professional Baseball Players, James L. White led off the first game with a stand-up double. It was May 4, 1871.

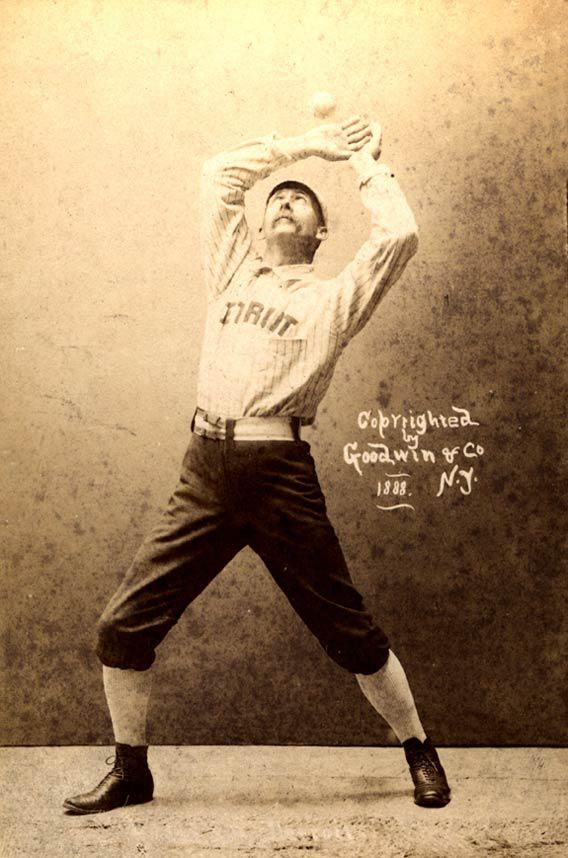

Courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library

The National Association lasted five years. Mismanagement killed it. Heavy drinking and gambling were rampant. Before the association died, Deacon played for the Boston team. While there, he batted .392 in 1873 and then .367 in 1875, the year he was awarded the first-ever Most Valuable Player award, not by the association but by the Boston fans. It was a silver chalice.

When the National League formed in 1876, Deacon moved to the Chicago White Stockings, the team that went on to become the Cubs. He was instrumental in that team’s winning the first National League pennant. He had his best year in 1877, playing once again for the Boston Red Stockings. In that one glorious season White was the National League leader in batting (.387), hits (103), triples (11), runs batted in (49), and slugging average (.545).

While in the National League, he also played for the Cincinnati Reds, the Buffalo Bisons, the Detroit Wolverines, and the Pittsburgh Alleghenys. When catching got to be too much for him, he switched to third base. Playing that position he helped the Detroit Wolverines win the pennant when he was nearly 40 years old. After a brief stint as a player-manager with Elmira in 1891, his career was over at age 43.

When Jim White started playing ball in Cleveland, the catcher had no mitt, no mask or helmet, no shin guards or chest pad, no cup. He did not crouch behind the plate, but stood back and caught the ball on the bounce. The only piece of equipment commonly worn by catchers in the late 1860s was a “rubber,” a primitive tooth protector.

Gloves came first—one thin one for each hand—and catchers had to learn how to catch with one hand and throw with the other, not an easy transition to make. In 1877, the catcher for the Harvard team showed White and several of his Boston teammates the first catcher’s mask. The approval of Deacon and his teammates helped to popularize this novel piece of equipment. Deacon himself soon went home and, with the help of a blacksmith, fashioned his own mask out of iron. It had no padding whatsoever and was held in place with a single strap.

In those early years, nearly all of the big leaguers had off-season jobs. One of Deacon’s Chicago teammates had a little side business making uniforms for the various athletic clubs. One day that teammate approached Deacon and asked if he minded if he made a few catcher’s masks to sell. Deacon said he didn’t mind at all, though he doubted there would be a huge market for them. And that’s how Al Spalding launched his sporting goods empire. White never saw a dime of that fortune, never dreamed that he would deserve to and, by all accounts, remained friendly with Spalding until the day he died. After all, he and Spalding formed the first great pitcher-catcher battery in baseball.

Years later, one of my relatives, probably Uncle Jim, contacted the Hall of Fame and asked if they were interested in a donation of Deacon White’s first catcher’s mask. They politely declined. They already had the one Spalding gave them. At least, that’s what I was told when I was a boy.

Grandpa White’s younger brother, Will, was a pitcher. Together they were the first brother battery in major league baseball. Will played for 10 years and came away with 229 wins—40-plus in three separate seasons. In 1879, he pitched 75 complete games and 680 innings, both records that still stand and will likely stand forever. Will holds the No. 10 spot on the all-time ERA list at 2.28. He was the first player to wear eyeglasses in a game. His friends called him Doc. He drowned in 1911.

Deacon was his younger brother’s mentor and family lore states that he taught Will to throw the curveball. I was raised to believe that Grandpa White invented the curve, but that has never been proven. The story I grew up with is that scientists and professors of the day were adamant that it was impossible to make a sphere curve in any direction other than a downward arc. Their contention was that a curving baseball was an optical illusion.

Deacon would have none of that. He hired a surveyor to place stakes in the ground between the pitcher’s point—there was no elevated mound back then—and home plate. The idea was to pitch the ball between the stakes, proving that it did indeed curve. The press was alerted and they, along with a throng of spectators, arrived at the ball field at the appointed day and hour. One can assume that gambling took place at this scientific exhibition, but I was also assured that Grandpa White, steadfast and upright Christian that he was, refused to wager.

Deacon grabbed the ball and, after appropriate pawing and squinting, threw three or four balls in a row to the catcher, all of which were well wide of the plate. The crowd jeered, the physicists smiled. The curveball was a fluke and White was a fraud.

After the crowd had calmed, Deacon very deliberately threw three perfect strikes, each of which curved between the stakes. And much money changed hands.

Did it happen that way? Probably not. And yet, years after I first heard that story, I read a similar account in E.L. Doctorow’s book Ragtime. Of course, that novel famously placed real historical figures in fictional situations. Did Doctorow make it up? I know I didn’t. I’m not that good.

Doc White was the pitcher, but Deacon was the first one to devise a new kind of wind-up. I didn’t hear this from a family member—I first read about it in an article written by David S. McCarthy, an Advent Christian pastor. While with Forest City, the young Deacon substituted for the team’s regular pitcher for several games. Deacon had been watching pitchers for years and thought there had to be a better way. On his own he had improvised a delivery that allowed him to propel the ball with greater velocity. The rules at that time dictated an underhanded pitch while maintaining a stiff arm and wrist. Deacon did all that but first whirled his arm overhead. A timeout was called after that first delivery amid vigorous opposition from the other team. Deacon prevailed and continued using the wind-up. Later the rules were changed to permit any kind of underhanded motion. So it is written, so it shall be. And so the catcher helped pitching evolve into what we know it as today.

Are you with me so far? James “Deacon” White was the first player to get a hit in a professional league. Later, he helped popularize the catcher’s mask and he was the first pitcher to go into a wind-up. He received the first MVP Award. He was in the first great pitcher/catcher battery with Al Spalding and the first brother battery with Will. He was in the first “Murderer’s Row” with Spalding, Ross Barnes, and Cal McVey. He was one of the first opponents of the reserve clause, famously stating, “No man is going to sell my carcass unless I get half.” He helped found the first, if short lived, player-owned league. And he believed with all his heart that the world is flat, because the Bible told him so.

***

After he retired from baseball, Deacon and his brother Doc opened an optometry shop on Main Street in Buffalo, N.Y. Doc was the optician, and Jim grinded the lenses and handled the business side. In his approach to his new line of work, the Deacon was reported to be “just as methodical in his ways as he was on the ball field.”

In 1909, the White brothers closed up the optometry shop. Deacon, his wife Marium, and his daughter Grace moved to Mendota, Ill. The Advent Christian Church had founded a small Bible college there and Grace enrolled as a student. Deacon and Marium were employed by the college as head residents.

Marium passed away in the mid-1910s, around the same time as Doc White’s accidental drowning. With Marium gone, Deacon wasted little time in contacting his old flame, the dark-haired Alice. She was also widowed and accepted Jim’s invitation to come to Mendota. After all those years, they were finally married. Grace White, meanwhile, married fellow student Roger Watkins. Their first two children, my Uncle Jim and Aunt Mim, were born in Mendota.

After a few years, Mendota College moved to a larger campus in Aurora, Ill., where it became Aurora College, today’s Aurora University. Deacon, Alice, Grace, Roger, and their two small children moved there, too. They all set up house at 221 Calumet Ave., a few doors down from the new campus. My mother and my Uncle Dan were born in that house. I spent the first three years of my life there.

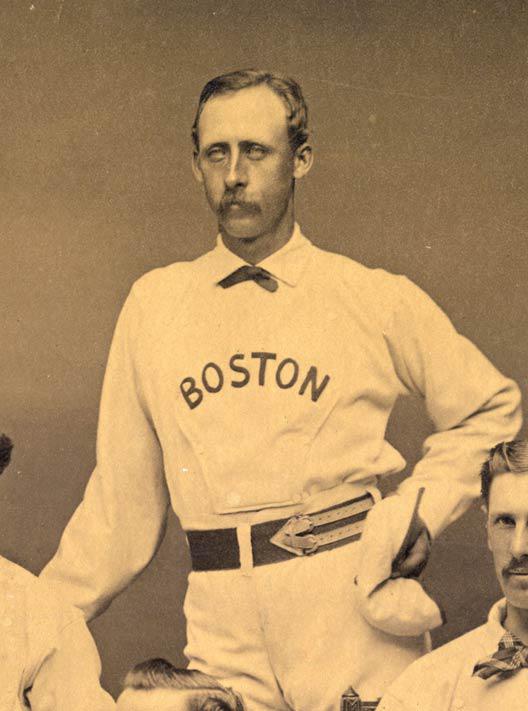

Courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library

Deacon spent his last two decades in an apartment next to my mother’s room, waiting for Jesus. As a devout Advent Christian, James White believed, as much as anyone could, that Jesus Christ would return to Earth in his lifetime. He sat in his rocking chair on the back porch, facing west as he believed that was the direction He would come from. And he rocked. And waited.

My mother, Betty Jackson, is 92. She is the last of Deacon White’s descendants who still remembers him. Because she was born some 30 years after Deacon retired as a player, she does not recall the dashing professional athlete, but rather the stern man with gnarled hands who used to bang his cane on the floor whenever he wanted something. To be fair, she may have never seen him smile simply because his walrus mustache reached to the middle of his chin, covering his mouth.

My mother’s memory has never been good. Names, dates, events—they all elude her. “My mind’s no good anymore,” she says. But somewhere in there is a little girl, peeking through a keyhole into the room next to hers. Sitting at the table is an old man who never smiles. In the dim light she sees him hunkered over, working with his hands on something. She knows his hands are big and bent, spotted and bumpy, like branches on a tree. More than one finger and both thumbs were broken years ago—hands that caught the ball and gripped the bat. Now they’re working on my mother’s toy sewing machine. It is her favorite, her prized possession. It was broken, but Grandpa fixed it. And she knew he loved her.

My mother says that Grandpa White was one of the first people in Aurora to own a radio. They would listen to the ballgames together in his room. Grandpa sat in his chair and my mother, aunt, and uncles sat on the floor, listening to a game played in a city far away, probably a city where the old man once played.

Once in a while, he would get out of that chair and watch the school baseball team practice. When I went to Aurora College in the 1970s, Charles Anderson ran the book store. He had played on the Aurora team in the 1930s. He told me Grandpa White was happy to give advice, but only if he were asked. The game had changed. Many of the college players didn’t know what the old man had done.

When he wasn’t waiting for Jesus or watching college baseball, Deacon looked out for the mailman. Deacon was waiting for the letter from Alice, the letter that never came. His first love had left him and gone back to New York, never to return. Did she grow tired of the increasingly grouchy old man, or did she just want to go back to her real home to grow old, far away from the provincial Midwest? I don’t know. Perhaps it was my grandmother Grace’s poorly concealed animosity for Jim’s second wife that drove her away. An only child, Grace had adored her mother and was furious that her father, who had missed much of her childhood, had been so quick to remarry after Marium’s death, and had made no secret that this new woman, Alice, was his true love.

So after she left, Deacon sat on the front porch and pined for Alice. Decades later, when my grandmother Grace died, her husband Roger remarried in a matter of months, which annoyed my mother and Aunt Mim to no end. And so it goes, my mom says today.

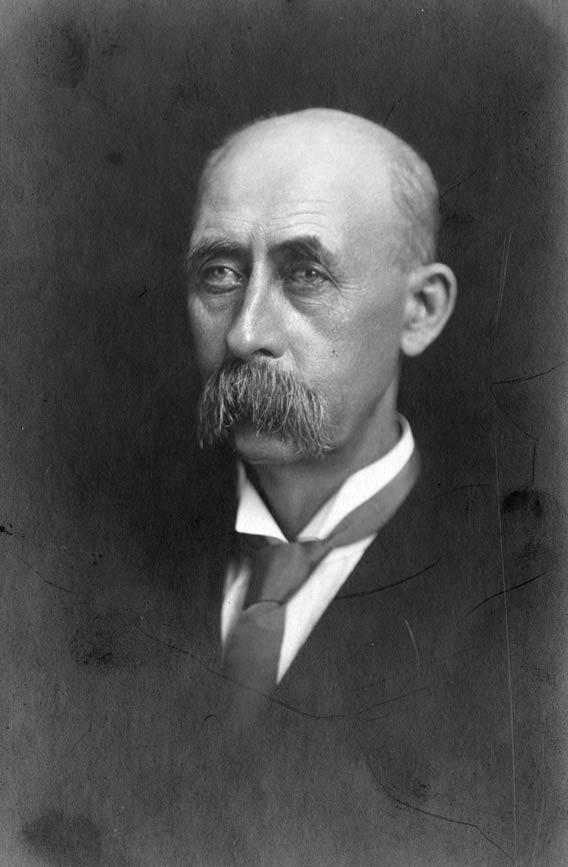

Courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library

There is not a lot left of the things Grandpa White owned. This weekend, the Hall of Fame will display Deacon’s old catcher’s mask, which is on loan from my brother. But the rest of the old equipment, the newspaper clippings, the moth-eaten caps—all gone. A cousin once told me about a thin metal card that entitled the bearer free admittance to any major league game, for life. I never saw it. But I do own one thing that is very dear: the gun.

Any man born in 1847 in upstate New York was, by necessity, an outdoorsman. To help put meat on the table, Grandpa White had a gun. Grandpa White gave my Uncle Jim, his namesake, that gun, and Uncle Jim gave it to me.

It is a beautiful, practical piece of art. A hand-crafted, muzzle-loading, cap-and-ball, over-and-under rifle/shotgun. Beautiful because it is all engraved metal and polished wood. Practical because it’s a small-bore rifle barrel on top of a single-barrel shotgun: one barrel for game, one for fowl. It has an adjustable “hair” trigger and came with a small mold into which you pour hot lead to make the balls, one by one. And it’s heavy, heavier than you would think.

I have never fired it. I just like to hold it and gaze down the barrel, through the sights. The hands that held it got the first hit in the first game ever played in a professional baseball league. But they also fixed my mom’s favorite toy. And the blood in those hands runs through my veins. I like to think that the gun, rather than the catcher’s masks, was Grandpa White’s Rosebud. It’s a stretch, I know, but the gun is all I’ve got.

***

In his excellent book Catcher: How the Man Behind the Plate Became an American Folk Hero, my friend Peter Morris writes that the Baseball Hall of Fame was conceived, in part, by Deacon’s old battery mate Al Spalding. In 1905, Spalding formed a committee that pushed the dubious proposition that the game was created by Abner Doubleday in Cooperstown, N.Y. In June 1939, the Hall of Fame finally opened, in Cooperstown.

Grandpa White believed, and rightfully so, that he should have been a shoo-in for enshrinement. The Sporting News certainly thought so, explaining that White “is entitled to be selected as typifying the Spirit of the ‘First Century of Baseball.’ ” By all accounts, Deacon was crushed when he was not selected. (Spalding, no stranger to self-promotion, won election in 1939 via the “old-timers committee.”) Worst of all, Deacon was not even invited to attend the Hall’s inaugural induction ceremony.

Why did it happen that way? No one knows for sure. The best guess is that, almost 50 years after he retired as a player, no one really remembered Deacon White. He played in a time without mass communication. The only real record was in the sports pages. Enshrinement was, and is, determined by the votes of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America, and not all of them had heard of Deacon White, let alone seen him play. They grew up with Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, and Honus Wagner. The 19th-century game—that was ancient history.

The month after the Hall of Fame opened its doors, my Aunt Mim was on a train travelling to Oregon. The conductor, a man who appreciated old-time baseball, stepped into her car and announced that the great catcher Deacon White had died that day. His last record: oldest former major leaguer.

My mother is now a few months older than Grandpa White was upon his death. She no longer drives her car. Every Monday, I drive us to the bank, post office, and drug store. She buys groceries, and she insists on pushing the cart herself. It holds her up, like a walker.

Last December, as we sat in her car in a parking lot, my mother’s phone rang. It was my brother Caddy. I hoped it was not bad news. It had not been a particularly good day. When the call ended, my mother turned to me and said, “Grandpa White was voted into the Hall of Fame this morning.”

And maybe I did a quick fist pump. I don’t really remember. What I do remember is my eyes turning wet as I looked out my window at the people going in and out of the Rite-Aid. And my mom said slowly, “After all these years. I just wish he’d lived to see it. I wish a lot of people had lived to see it.”

If there is a heaven and if you get in by being devout and devoted to Jesus, then Grandpa White is there, happily wandering through the broad, sun-lit uplands. Thank you, Grandpa White. Thanks for the name, thanks for the gun, and thanks for the good game you played. Say hello to Jesus. Give him my regards. Tell him I’m trying. And I’ll see you at Cooperstown.

By Dale Lancaster

The baseball cranks all sneer at me,

And poke a lot of fun,

Because I tell of plays they made

In the days of seventy-one.

And yet, who cares for fun and sneers?

By gum, I know I’m right!

Somehow the game ain’t played the same

As ‘twas by old Jim White.

They talk about their great Lajoie,

And Wagner and McVeigh [sic];

To hear ‘em yarn, you’d think, by darn,

Nobody else could play.

And yet I often call to mind

Those scenes of wild delight

When ‘cross the fence some hit immense

Was smashed by old Jim White.

And Lordy! How old Jim could catch!

He’d stand and dodge the bat

‘Thout mask or mitt—it took some grit

To catch great speed like that.

He’d nail ‘em high and scoop ‘em low—

It was a thrilling sight;

No player dared—he’d be too scared—

To catch like old Jim White.

So when you sing of modern stars

Don’t call the old ‘uns slow;

They knew the game and played it too

Some fifty years ago.

And while o’ course, the players now

Are men o’ grit and might,|

Somehow the game ain’t played the same

As ‘twas by old Jim White.

Special thanks to Peter Morris for his research assistance.