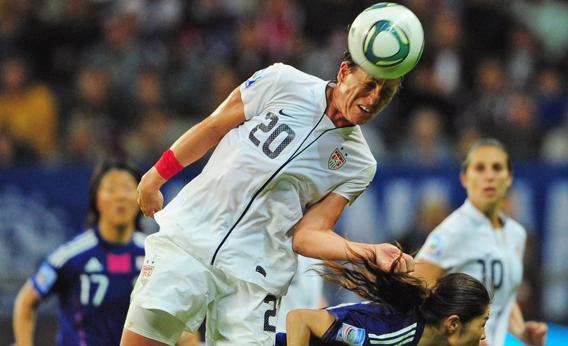

When American soccer star Abby Wambach was drilled in the head by a ball on April 20, it was obvious she was at risk for a concussion.* For 11 days, though, Wambach and her team, the Western New York Flash, didn’t so much as say the word.

On Wednesday, the National Women’s Soccer League did the right thing. It admitted that Wambach did sustain a concussion in the final minutes of a road game against the Washington Spirit. It conceded that the referee erred in barring medical personnel from coming onto the field to examine Wambach. It admitted that Wambach should have been removed from the game. And it pledged to use the episode to better inform players, coaches, trainers, and fans about the risks of head injuries.

“This is a situation that wasn’t handled as we should have handled it,” Neil Buethe, a spokesman for the U.S. Soccer Federation, which is helping to run the new women’s league, told me. “We admit that. We’re going to refocus to make sure referees, players, coaches, everyone has a better grasp going forward of how to handle concussions.”

A mea culpa from a sports league is a rare thing. The multibillion-dollar pro leagues are too often concerned about image to risk what elsewhere might be called honesty, and small leagues like the NWSL aren’t generally visible enough for anyone to care. But in its own sphere, this new women’s soccer league, with a preponderance of preteen and teenage girls in the stands, can have an outsize voice on a serious matter. According to multiple studies, girls playing the same sport as boys, especially soccer, suffer concussions at higher rates and recover at slower rates.

Put the two together—sizable girl fan base, serious concussion problem among said fan base—and it’s obvious why a women’s league headlined by athletic celebrities like Wambach and Alex Morgan can have an impact on the lives of girls. Organizations like the Women’s Sports Foundation have long emphasized the role-model potential of women jocks, in particular the handful of female athletes who earn mainstream media attention. Girls simply have fewer stars in the sports pantheon to emulate, and those athletes receive less exposure than their male counterparts, as any issue of Sports Illustrated for Kids demonstrates. (When the magazine arrives in our house, my 10-year-old daughter looks for female athletes and then comments on how few there are.)

That’s one reason I was so hard on the women’s league and Wambach, both in an article after the game and a follow-up earlier this week. The other reason is that, with all of the medical and media focus on concussions, it was appalling to see a referee prevent an athletic trainer from examining an athlete who was on the ground clutching her head. Buethe told me that the ref, World Cup and Olympic veteran Kari Seitz, talked to Wambach after the blow to the head and that Wambach said, as athletes will, that she was fine. “We are going to restate to officials the importance of letting medical staff come and make a determination,” Buethe said, adding that Seitz will not be disciplined. “The big goal here obviously is the safety of the players.”

Amen to that. Buethe also said the league would talk to coaches and trainers about the soccer federation’s head-injury guidelines, which the new league follows. That’s important, too, because while Seitz deserves blame, Flash coach Aaran Lines could himself have subbed Wambach out of the game. But the injury happened in the 90th minute of regulation of a 1-1 tie with three minutes of additional time to come. The coach was thinking about winning. The Flash had a better chance to win with any version of Wambach on the field, Lines likely figured, so he let her play on. (He’s not alone, of course. Recall that Washington Redskins coach Mike Shanahan left his hobbling rookie quarterback Robert Griffin III in a playoff game in January only to see him blow out a knee. This week, Griffin admitted that he should have taken himself out of the game.)

Buethe said, and the women’s league reiterated in a statement, that an internal review by the federation showed that Wambach’s care was handled correctly once she reached the locker room. He said that the Flash’s athletic trainer and a doctor for the home team, the Spirit, examined Wambach before and after she showered and determined that she had symptoms of a concussion. The doctor cleared her for the seven-hour overnight bus ride to Buffalo, N.Y. The team trainer sat with Wambach on the ride.

Once home, Wambach was monitored daily by medical professionals, Buethe said. She continued to show concussion symptoms until that Wednesday, April 24, when her scores on a baseline concussion test matched those from two years ago, when she was tested by the soccer federation.* After that, Wambach was allowed to begin the federation’s return-to-play protocol, which requires a week of gradual increases in training with no symptoms. On Tuesday she was medically cleared to return to game action. Wambach suited up on Wednesday night, playing every minute and scoring a goal in a 2-1 win over New Jersey’s Sky Blue FC.

As part of its review, U.S. Soccer brought in Ruben Echemendia, a neuropsychologist and concussion researcher who works with the U.S. national teams and has consulted with other sports leagues and clubs. Buethe said that Echemendia concluded that the Flash and league did follow proper post-injury protocols.

But Wambach’s care was botched terribly on the field, and the team, player, and coach compounded that with a series of misleading, illogical, and uninformed statements or nonstatements: refusing to say that Wambach had a concussion; asserting that she was symptom-free when she wasn’t; saying that she was kept out of a game last week as a “precaution” when it fact she hadn’t been cleared medically; and, my personal favorite, appearing to blame the National Football League for the very existence of return-to-play guidelines. (“She’ll tell you right now that she’s fine but there are certain procedures [to follow] … and it’s come of late through what’s happened in the NFL,” the Flash’s coach said.)

But good for the league for doing the right thing in explaining what happened, what didn’t, and what should. “This is for us now a case study,” Buethe said. “We’re going to break it down and explain how it should happen going forward. We’re going to use it as a learning experience.”

Externally, the league can try to emphasize to its fans the importance of recognizing and treating concussions. Michael Sokolove’s 2008 book Warrior Girls argues that, when it comes to staying on the field or returning to play after an injury, female athletes can be tougher than male ones: more willing to play through pain, more worried about letting down their teammates. One way to convey the message that it’s possible to be tough and smart and safe all at once is through athletes like Wambach.

Before Wednesday’s game, U.S. women’s national team coach Tom Sermanni called Wambach “a great ambassador for women’s football.” No one can force her to demonstrate that by becoming a spokeswoman for a cause. But on a day when she returned to the field following a scary injury—one that many other female soccer players have suffered themselves— all the reigning world player of the year had to say on Twitter was that she was “So happy about those 3 points!!”—the three points the Flash received in the standings for winning.

Wambach should be happy about a lot more—that her brain wasn’t injured more severely, that she was able to recover quickly—and she should tell her fans why.

Correction, May 2, 2013: This piece originally misstated the dates of Abby Wambach’s head injury and concussion test. They occurred on April 20 and 24 respectively, not March 20 and 24.