The First Black Player in Major-League History

Was it William Edward White?

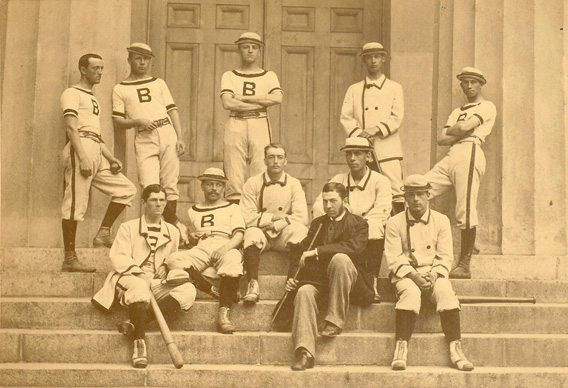

Courtesy of Brown University Archives

On the April 15 edition of the Hang Up and Listen podcast, Stefan Fatsis told the story of a possible African-American baseball pioneer named William Edward White. The transcript of Fatsis’ account is below, and you can listen to the story by clicking on the audio player beneath this paragraph.

It is Jackie Robinson Day, and that means a flurry of stories about African-American baseball pioneers. The New York Times has one this morning, about Bud Fowler, who, when he suited up for the Lynn Live Oaks of the minor-league International Association in 1878, might have been the first black professional ballplayer. Fowler is the subject of an upcoming biography, a paper will be presented about him at the Society for American Baseball Research’s annual conference in Cooperstown this weekend, and he’s having a street named for him in Cooperstown because he grew up near there.

Fowler played 10 season of professional ball, all of it in the minors. Other blacks—most notably Frank Grant and Sol White—played in minor and semi-pro leagues in the 1880s before baseball imposed its gentlemen’s agreement racial barrier. The other name you might know is Moses Fleetwood Walker, who played 42 games for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association in 1884. He’s usually credited as the first African-American to play in the majors.

But every Jackie Robinson Day, I think of William Edward White, who was in all likelihood actually the first African-American major leaguer. White attended Brown University. On June 21, 1879, he filled in for the big-league Providence Grays of the National League. White got a hit, scored a run, fielded 12 plays flawlessly at first base—and never played in the majors again.

The background of William Edward White would have been lost to history were it not for researchers on SABR’s biographical committee, which is devoted to compiling biographical data for all 16,000-plus men who have played in the major leagues. The SABR guys had some basic data on William White. He was born in Milner, Ga., didn’t graduate from Brown, father was A.J. White. But that was it. Then a check of 1880 census data revealed that the only A.J. White in Milner was a former slaveholder named Andrew J. White, and living with him was 35-year-old mulatto, Hannah White. The 1870 census showed that Hannah White had three children—including 9-year-old William White.

That William White attended Brown wasn’t surprising to the researchers—it wasn’t unusual for blacks or people of mixed race to do so at the time. Brown was a Baptist school then; Andrew White was wealthy and built a Baptist church in his town. The final pieces of White’s story were pieced together by a SABR researcher named Peter Morris. Peter has written books about baseball’s early era, innovations that shaped the game, the history of catchers and groundskeeping. (And he’s also a, by the way, former world and national Scrabble champion.)

Peter was intrigued by the emerging details of the White story—a guy who was one-quarter black, which made him legally black in most states, who in the one photo that turned up of Brown’s baseball team does appear to have darker skin, who listed his race as white on the 1880 census. So in January of 2004, I met Peter Morris in Georgia, and we went on a hunt for the smoking gun that would prove William Edward White’s background.

We found lots of information about A.J. White, but nothing about his children, not until our third stop, the courthouse in Zebulon, Ga. And there a clerk pulled down two plastic binders that contained all of the wills recorded in Pike County from 1867 to 1912. On Page 148 of the first binder, we found Andrew White’s will. "Item Fourth. All the balance of my Estate, both Real and Personal of Every Kind and description ... I do hereby ... bequeath unto William Edward White, Anna Nora White, and Sarah Adelaide White, the children of my servant Hannah."

Peter turned to me, and he said, "There's your proof."

The will said that William—now at school in the North—be able to complete his education. That it didn’t identify White as his son wasn’t unusual in the South after the Civil War—and White was listed as his son at Brown. But that he left all of his money to his “servant” was pretty much confirmation of their actual relationship.

I wrote up the story, it ran on Page 1 of the Wall Street Journal, it got a fair amount of pickup. But nine years later, William White isn’t part of the conversation about early black players. As far as I know, he’s not mentioned at the Hall of Fame. [Update, April 24: Tom Shieber of the Hall of Fame reports that White is briefly mentioned in an exhibit called "Pride and Passion: The African-American Baseball Experience."] SABR’s biographical committee doesn’t have a bio—even a short one—for White on its website. He’s not on SABR’s list of “one-gamers” either.

The baseball question is whether the sport should recognize a one-quarter black man who played one game as a substitute, and possibly did that without anyone knowing that he was black. Still, there are unanswered questions: Why didn’t White play again? Did his teammates discover that he was black and refuse to have him be part of the club anymore? Part of the problem is that the trail on William White runs dry. Peter Morris told me today that he’s had a few stray leads on the rest of White’s life, and those of his sisters, but nothing has come of them.