Some 500 Major League Baseball players traded in their team uniforms for service uniforms during World War II. With so many men absent from the diamond, the sport marched on from 1942 to 1945, though it was just a shadow of the real thing—“the tall men against the fat men at the company picnic,” in sportswriter Frank Graham’s matchless phrase.

Many of the players who did join the military during the war years—especially stars like Joe DiMaggio and Stan Musial, were kept from the front lines. They played service ball in the United States and in Hawaii (then still a U.S. territory), in exhibitions that entertained the troops before they went off to war. But those without reputations to protect them, including the vast majority of minor leaguers, went off to combat.

Ad hoc games abounded among deployed servicemen (and in POW camps) during the war, but there was little formal play. That changed when the Nazis surrendered in 1945. The U.S. Army decided the best way to keep hundreds of thousands of its (restless and heavily armed) soldiers occupied was to set up, virtually overnight, a massive athletics apparatus, with intramural competition in every sport imaginable. Baseball was the most popular game among the G.I.s, and a large league was formed, with representatives from most of the divisions in the theater.

A majority of the games were played in a most unusual site—the conquered, repurposed Stadion der Hitlerjugend, the Hitler Youth Stadium in Nuremberg, home to Nazi Party rallies just a short time before. Now, the swastikas were painted over and America’s national pastime was put on display.

A team of major and minor leaguers, representing the 71st Division of Gen. George Patton’s Third Army, easily won the championship among German-based teams. It was decided that the “Red Circlers” (so-called for the distinctive patch of the unit) would play a best-of-five World Series against the best team from France to determine the champion of the European Theater of Operations (ETO).

Some 50,000 doughboys of every rank and specialty poured into Nuremberg for the opener of the ETO World Series on Sept. 3, 1945—one day after Japan surrendered to end the war. The infield was finely crushed red brick, the outfield perfectly mown green grass. German POWs had been ordered to build extra bleachers to accommodate the large crowd. A brilliant sun warmed the faces of the G.I.s. Vendors sold beer and Coke and peanuts, just like back home. The Stars and Stripes flew over the field, and a bugle corps played the national anthem before the cry of “Play ball!” Armed Forces Radio had a setup behind one dugout, transmitting the action to the boys who couldn’t be there. For those in the stands, sitting in the sun and drinking beer, this afternoon reminded them of what was soon to come—a return to their families and the simple pleasures of their favorite game.

The 71st was led by well-known players like Harry “The Hat” Walker of the St. Louis Cardinals and Ewell “The Whip” Blackwell of the Cincinnati Reds. Walker had been put in charge of the entire German-based baseball operation, and unsurprisingly had stocked his team with transfers from other units. He even commandeered a B-17 bomber, called Bottom’s Up, to ferry the teams around the country to play.

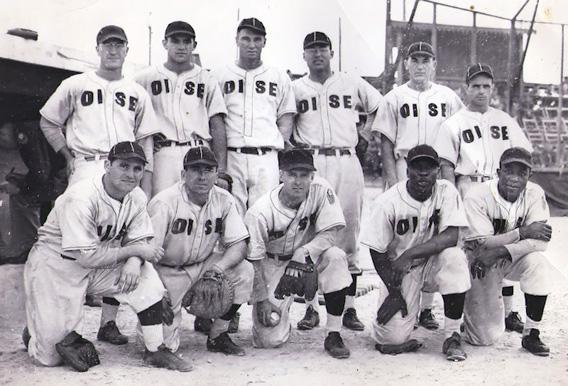

Courtesy of Little, Brown

Their French-based opponent, the clumsily named Overseas Invasion Service Expedition (OISE) All-Stars, was a ragtag outfit, made up mostly of semi-pro players, picked from the relatively few units that hadn’t moved on to Germany or back to England. Their lone “name” player was the France-based equivalent of Walker, a journeyman pitcher named Sam Nahem. He had only a fraction of the manpower Walker could draw upon for his team, which was thus a huge underdog to the Third Army juggernaut. OISE did have two secret weapons, however, one a slugging outfielder and the other a dominant pitcher. They were a secret to most of the white men in attendance because as of September 1945, Major League Baseball hadn’t yet integrated.

Willard “Home Run” Brown would eventually hit the first round-tripper ever clubbed by a black man in the American League, with the St. Louis Browns in 1947. Leon Day was a star hurler for the Newark Eagles of the Negro Leagues, alas too old by war’s end to receive much interest from the majors.

Day landed on Normandy Beach on June 12, 1944, six days after D-Day, driving an amphibious supply vehicle called a “duck.” He was, in his words, “scared to death.”

“When we landed we were pretty close to the action because we could hear the small arms fire,” he told Negro Leagues historian James Riley. One night, shortly after landing, a wave of German fighters appeared over the beach, “dropping flares and (lighting) the beach up so bright you could have read a newspaper.” Day evacuated his ammo-laden duck and jumped into a sandbagged foxhole, manned by a white MP. As the Luftwaffe strafed the beach, the MP shouted, “Who’s driving that duck out there?”

“I am,” admitted Day.

“What’s it got on it?”

“Ammunition.”

“Move that duck from out in front of this hole!” screamed the MP.

“Go out there and move it your own damn self!” Day replied.

Though Day wasn’t reprimanded for his actions, Jackie Robinson would be court-martialed soon after D-Day for similar defiance of whites. (Robinson had declined to move to the back of a military bus when ordered.) What’s striking about the games in Nuremberg is how little comment there was about the presence of the Negro Leagues stars. If the throng on hand knew what was coming just over the horizon, they might have paid more attention. They were witnessing an out-of-town preview of baseball’s new frontier, a year and a half before Robinson’s Brooklyn Dodgers debut.

The German World Series started inauspiciously for “Home Run” Brown and his teammates. Ewell Blackwell dominated in Game 1, collecting nine strikeouts in an easy 9–2 win. OISE made it easy for them, committing seven errors. But Leon Day evened matters the next afternoon, Labor Day back in the States. A holiday vibe infused the shirt-sleeved crowd, which again numbered close to 50,000. The man the New York Times misidentified as “Leo Day” hurled a four-hitter, all scratch singles, winning 2–1 to even the Series.

The teams traveled to Riems, France, for the next two games, which they split, setting up a decisive Game 5 at Soldier’s Field, as the Stadion had been renamed.

Once again, it seemed like everyone in the country with an American uniform and a pass turned out to watch. They would witness a dandy affair. Stars and Stripes raved, “The game was so close all the way through that it kept the crowd of over 50,000 on its feet cheering wildly and rewarding unfavorable decisions with sounds as wild as any ever to emerge from Ebbets Field or the Polo Grounds.”

Blackwell started once more for the Red Circlers and was throwing darts again, though he also committed two errors in a sloppy game “replete with miscues and thrills,” according to the New York Times. The 71st led 1–0 in the seventh inning when Day, who was sent in to pinch-run, stole second and third and came home on a short fly ball to tie the game. This was the sort of hard-charging ball that was on display every day in the Negro Leagues, soon to be brought to the majors by the likes of Robinson, Larry Doby, and Willie Mays.

In the eighth inning, it was Brown’s turn. With a man on first he clubbed a double to the deepest reaches of Soldier’s Field. Harry Walker ran it down and relayed the ball in, but the runner beat the throw after a dramatic dash that had the crowd roaring.

Trailing 2-1, on the verge of being the victims of a monumental upset, Walker then came to the plate hoping to start a rally and avoid a humiliating loss. Though he received a Bronze Star, a Purple Heart, and several commendations for his wartime service as a recon scout, he wouldn’t be a hero on this day. He flied out, and moments later, Day, Brown, and the OISE All-Stars were celebrating, having won the series three games to two.

Back in France, the winners were feted by Brigadier Gen. Charles Thrasher. There was a parade, and a banquet complete with steaks and champagne. Day and Brown, who would not be allowed to eat with their teammates in many major-league towns, celebrated alongside their fellow soldiers.

Meanwhile, Harry Walker stewed. He was more upset at losing than he thought he would be. The Hat vowed that back home, if he got another crack at a big game, he would come through.

Indeed, a little more than a year later, on Oct. 15, 1946, the Cardinals’ Walker came to the plate in the bottom of the eighth inning in Game 7 of the World Series against the Red Sox. The score was tied 3–3. With two out and Enos Slaughter at first, Walker poked a hit into left-center field. Slaughter, shocking everyone, tore around the bases and came all the way home, helped by a slight hesitation on the relay throw by Sox shortstop Johnny Pesky. The Cardinals went on to win the game and the World Series 4-3, capturing the first post-war championship.

Slaughter’s Mad Dash and Pesky’s double clutch would go down in baseball lore, one of the most famous and dramatic moments in hardball history. The ETO World Series, by contrast, has been mostly forgotten. But there was Harry Walker, smack dab in the middle of both.

This piece has been adapted from Robert Weintraub’s book The Victory Season: The End of World War II and the Birth of Baseball’s Golden Age, which is out today. You can view the book trailer here.