In 2009, Zinedine Zidane, the legendary soccer player, participated in a coaching clinic in Ajinomoto Stadium in Tokyo, Japan. Children and parents filled the stands. The mood was jovial. Zidane was a once-in-a-generation sort of player, a kind of mad genius remembered today as much for his ball skills as for the infamous 2006 World Cup headbutt. The parents in attendance hoped some of those skills, like his signature pirouette (not the headbutt), would rub off on their children. But as Zidane and the gathered coaches began their lessons, something strange happened. The children in the audience began to chant. They weren’t chanting “Zidane,” although people occasionally shouted for his autograph. The children chanted “Tomsan,” the nickname of a 52-year-old retired player from upstate New York who never won a Champions League title, a World Cup Golden Ball, or a FIFA World Player of the Year award: Tom Byer.

Byer played briefly in Japan in the late 1980s, before retiring to work as a youth coach. Today, many in Japan see him as a major catalyst behind the country’s rising status as a global soccer power, responsible for increasing soccer’s popularity and teaching fundamental skills to hundreds of thousands of children, including many of the nation’s most celebrated players. In 1988, the year Byer hung up his cleats, the Japanese men’s and women’s national teams weren’t even successful regionally. In 2011, the Japanese men took home the Asian Cup for a record fourth time, and the Japanese women’s national team won its first World Cup title.

Although what Byer achieved is notable, how he did it is the fascinating part. He started off running a no-name, grass-roots soccer clinic and within a decade, he’d become a fixture in Japan’s most popular children’s comic book and a character in the country’s leading morning kids’ show. Tom Byer is the Mr. Rogers of Japanese soccer. There’s nothing in America like him, and as both the Japanese and American men’s squads prepare for World Cup qualifying matches next month*, it’s worth thinking about what the U.S. program could learn from Byer’s Japanese success.

Byer’s playing career started in 1983, the worst possible time for an aspiring American pro. The North American Soccer League was on the verge of collapse and MLS was more than a decade away. Things weren’t much better in Europe, where the sport, scandalized by hooligans, had begun a kind of low ebb, punctuated by a series of stadium disasters. But Byer’s short, nomadic career brought him to Japan, a country he fell in love with.

“Back in those days, if you were a good juggler of the soccer ball, you could entertain,” he said. So after retiring, he started a traveling youth soccer clinic based as much around his ability to “catch people’s eyes” with juggling tricks as his coaching chops. He didn’t speak much Japanese, and in order to set up gigs, he cold-called English-speaking institutions around Tokyo, like U.S. military bases and international schools.

In 1989, during a clinic at a Canadian school, Byer learned that one of his students, a young boy, was the son of a Nestlé employee. Byer needed outside funding to expand his business, and about a week after the clinic, out of ideas, he decided to take a chance and call the boy’s father. He scoured the phone book, and dialed what he guessed was the right number. To his relief, the boy answered. Byer asked to speak to the boy’s father but first asked what his dad did at Nestlé. The boy said, “He’s the president.” A week later, Byer signed an agreement with Nestlé to sponsor 50 clinics in a yearlong, nationwide tour. During each clinic, Byer had to give out samples of Milo, an Ovaltine-like chocolate drink, but it was a small price to pay for his first big break.

Although he now had financial backers (Nestlé sponsored him for the next 11 years), Byer did not consolidate his coaching philosophy until 1993, when he opened his first soccer school, which has since expanded to 100 campuses with roughly 20,000 pupils nationwide. That year, Paul Mariner, the former head coach of Toronto FC, introduced Byer to a technique-based approach to youth development called the “Coerver Method.” It changed the way Byer viewed coaching.

Created by Wiel Coerver, a Dutch coach, the method is a quasi-academic system based on specific skill acquisition. Rather than putting kids on a field and having them chase the ball around—which is how most young kids practice across the United States—it teaches close ball control and situational, one-on-one moves: stopovers, feints, various ways to manipulate the ball with the sole of the foot. Tactics and passing come later, once the kids master ball control.

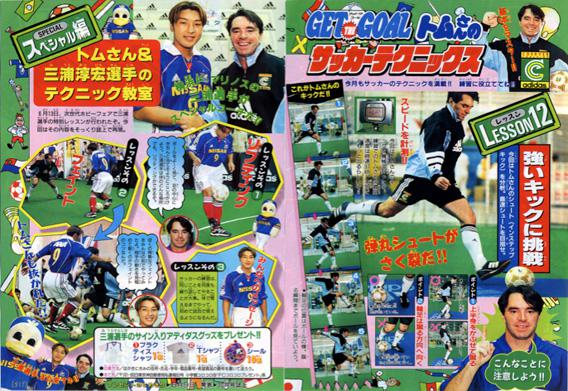

In 1998, Japanese broadcasters seized upon the upcoming World Cup as the perfect moment to begin promoting the 2002 tournament, which would be held in Japan for the first time ever. Executives at Tokyo TV and ShoPro, a production company, added a two-minute soccer spot to Oha Suta, the top-rated children’s morning show, and they asked Byer to host. Suddenly, instead of standing in front of a few hundred young soccer players a couple times a week, Byer was teaching his skills in a green screen studio, backed by animated stadiums and fans. From 3 million to 5 million children saw him every single day.

At the same time, executives from the affiliated Shogakukan publishing company offered him a two-page panel in KoroKoro Komikku, Japan’s biggest children’s comic book. The United States has no equal to the cultural giant that is KoroKoro. The monthly comic book has an enormous circulation—Byer puts it at about 1.2 million (for comparison, in 1977, during its heyday, Mad magazine circulated 2,132,655 copies in the entire year, in a country that’s more than double the population of Japan) and a readership in the neighborhood of 3 million Japanese preteens. The magazine is hundreds of pages long and shares storylines with Japanese video games. It played a big role in transforming Kirby and Pokémon in to global media juggernauts.

“The comic book was to promote soccer, to inform people about the technical side, it was to highlight the stars and try to inspire and motivate kids,” Byer said.

It worked.

The print and TV programs were a kind of tag team that helped ignite excitement for soccer in Japanese culture. (According to a recent survey by NHK, a Japanese toymaker, soccer is now more popular among Japanese boys than baseball). Oha Suta aired every day, right before school, perfect for motivating playground training sessions. KoroKoro, meanwhile, put soccer practice on the same level as the country’s most esteemed cartoons and superheroes.

Today, Japanese pros in men’s and women’s soccer credit Oha Suta and KoroKoro as key parts of their soccer education. Keisuke Honda watched the show, and Byer worked with Tadanari Lee as a boy. Byer’s most famous disciple is Shinji Kagawa, a midfielder at Manchester United renowned for his technical ability. Last year, a profile of Kagawa in one of the team’s match-day programs name-checked Byer and referenced his show and the comic.

While praise from Kagawa and others is nice, Byer maintains that the production of top players is only a side effect of what he’s accomplished, which was to raise the baseline level of youth soccer in Japan. According to Byer, for a child to develop into an elite player, he or she must face constant challenges. Once a player becomes so dominant over her peers that she doesn’t need to really work, her development stops. Complacency is the enemy. Byer’s program succeeded in raising the play of the worst, providing more of a challenge to the best, and that has resulted in a deep pool of top professionals.

His secret, he says, “was to empower children to practice on their own.” Practicing alone sounds quite boring, but Japanese kids do just that. Perhaps there’s a cultural explanation here—it’s almost a cliché to note that the Japanese value a strong work ethic—but there’s another explanation too: Byer’s lessons build on-the-ball confidence, which is really the skill set needed to make soccer fun. Practicing alone might not be fun, but nutmegging your unsuspecting friend the next day at school sure is.

Close followers of U.S. soccer have no doubt read the above with some creeping angst and perhaps a pang or two of jealousy. The U.S. has never developed a player of Kagawa’s skill, a fact that elicits a great deal of handwringing on this side of the Pacific. (We can argue about Landon Donovan and Clint Dempsey, but the point is that Japan has a team full of players capable of breaking down defenses off the dribble and the U.S. does not.) Just about everybody has an idea about how to fix that, and the U.S. Soccer Federation recently revamped its youth development setup, largely as a means to address the exact kind of complacency-breeding talent gap that Byer talks about. (He told me that in the United States, this gap was “like an ocean.”) And while the USSF’s new academy setup is a step in the right direction—it brings the nation’s most talented players into a more competitive setting—players must be eligible for the under-13 team to even participate. By that age, Japanese kids have already spent 9 years learning to pirouette like Zidane.

Byer argues that his program is exportable to the United States. In some ways, in the U.S. it’d be easier to implement than in Japan: Soccer is already the No. 1 sport among American youth. The problem, according to Byer, is that the USSF and MLS “look at grass-roots football as an obligation, not an opportunity.” Why not put a small technique spot on the Disney Channel or Nick Jr.? Kids would surely pay attention.

Some American kids are lucky, Byer points out, and get a coach who really knows soccer—“but you might get a coach who’s crap.” Parents, who typically coach the youngest American players, don’t realize kids as young as 5 are capable of learning advanced ball skills, and they don’t know how to teach them. “The whole idea [behind my program] was to be consistent and teach that technique work.”

Don’t look to Byer to launch a program in his home country, though. In August, he signed a three-year contract with the Chinese Football Association. He’s the head technical director of a program overseeing the development more than 2 million kids. If all goes to plan, there will be some Chinese Kagawas on Europe’s biggest teams in 15 years or so. But until the U.S. gets its elementary school-aged kids out there, practicing, and shows them it can be fun, we might have to wait a little longer.

*Correction, Feb. 26, 2013: Because of a production error, this article referred to the wrong date for the World Cup qualifying matches. They are in March.