Go see a special live performance of Slate’s sports podcast Hang Up and Listen in Washington, D.C. on Monday Oct. 1. Click here for more information and to buy tickets.

Three blind mice, three blind mice,

See how they run, see how they run,

They all ran after the farmer’s wife,

Who cut off their tails with a carving knife,

Did you ever see such a thing in your life,

As three blind mice?

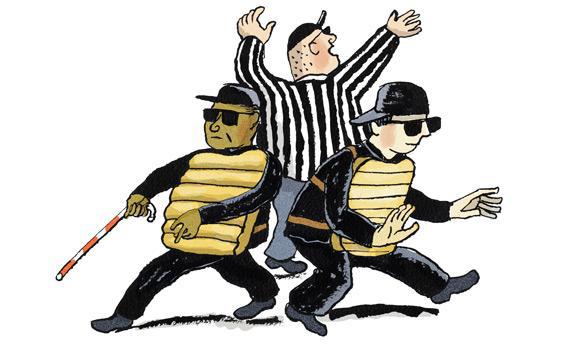

Those are the modern words to “Three Blind Mice,” that pleasant enough English nursery rhyme that we all remember from our youth. Back in the early 17th century, when the folk round was first published, that language was completely different. Words like scrapte and licke made it seem more sinister, as did the purported reference to Queen Mary ordering the execution of defiant bishops. Today, the song has lost those sharp edges for everyone but one small group: those beleaguered souls who make a living calling balls and strikes.

Consider Mario Seneca. Last month, the minor league umpire ejected a Daytona Cubs intern after the 21-year-old University of Illinois student dared to play “Three Blind Mice” over the park’s public address system in protest of a close call. As you can hear in the video below, Seneca points to the sky and shouts “You’re gone!” The reaction of the Cubs’ broadcaster: “That is absolutely awesome!”

Fans at Jackie Robinson Ballpark immediately booed the fully sighted Seneca, who Deadspin later deemed “the most sensitive umpire in baseball history.” The unpaid intern, who was fined $25 by the Florida State League for getting thrown out of the game, parlayed his infamy into a handful of media appearances. He even made it to SportsCenter.

Seneca, meanwhile, has made no public comments, allowing the sports media to make like an angry manager and rain spittle on his expressionless face. Justin Klemm, executive director of the Professional Baseball Umpire Corp., which governs minor league umps, says this silence is intentional. “Mario has decided not to talk about this and we’re respecting his wishes,” Klemm told me.

If Seneca won’t defend himself, Kevin O’Connor will. An umpire evaluator for Major League Baseball who spent 10 years behind the plate himself, O’Connor had a similar brush with notoriety in 1985. As he tells it, O’Connor was working a game in the Florida State League when a coach got in another ump’s face about an inning-ending call at first base. “That’s when Wilbur started playing ‘Three Blind Mice,’ ” O’Connor says. “I threw him out immediately and I was backed by the league 100 percent because I told him earlier in the season he couldn’t do that.”

Wilbur was Wilbur Snapp, a ballpark organist whose quick thinking and subsequent heaving won him mentions from Willard Scott and Paul Harvey, along with requests to sign autographs as “Wilbur Snapp, Three Blind Mice organist.” When he died 18 years after he got the thumb, the New York Times saw fit to run his obituary: “Wilbur Snapp, 83, Organist Ejected by Ump.”

O’Connor insists that snapping on Snapp was the right call, and not just because he’d already warned him against playing the song. Playing “Three Blind Mice”—well, it’s “just not done,” O’Connor says. While he admits that “from an outsider’s view it’s funny,” to an umpire “it’s a derogatory thing that’s only going to incite the crowd. … It’s not cute when you’re the guy on the field and you don’t know what the reaction’s going to be.”

Both O’Connor and Seneca are backed by the PBUC manual, along with decades of precedent. Fans and managers and players have been questioning umpires’ eyesight since the day baseball was invented. Bob Emslie, who began umping in the 1880s, was given the nickname “Blind Bob” by legendary manager John McGraw. A more general pejorative, “Blind Tom,” became associated with baseball arbiters in the early 20th century.

Despite the quotidian nature of these vision-related insults, “Three Blind Mice” has always had a special power to enrage. Umpires have been chucking anyone with the temerity to so much as hum the song since at least 1936. According to an Associated Press report from July of that year, umpire and Norman Rockwell subject Beans Reardon “chased [pitcher] Jim Weaver off the Pittsburgh bench” for singing the song, proving that if catchers wear the tools of ignorance, umpires don the tools of sensitivity.

In 1941, the Cubs expanded the possibility of song-based heckling by introducing the first ballpark organ. Though Wrigley Field ivory tickler Roy Nelson stuck to friendlier fare, the musicians weren’t as kind in Brooklyn. In May 1942, Ebbets Field’s Gladys Goodding welcomed Bill Stewart, Ziggy Sears, and Tom Dunn to the field with umps’ least-favorite nursery rhyme. “It was a request number from a fan,” UPI reported.

The fan may have been a part of the Dodgers Sym-Phony, a ragtag band that kept up a running commentary on the on-field action with a rotating cast of horns and drums. “Three Blind Mice” was long part of the Sym-Phony’s repertoire, along with “The Hearse Song” (“The worms crawl in, the worms crawl out/ The worms play pinochle in your snout/ They eat your eyes, they eat your nose/ They eat the jelly between your toes”).

“The Brooklyn Sym-Phony used to be the worst for us—they would always play ‘The Three Blind Mice’ when we’d walk out on the field,” Beans Reardon said in a 1949 interview. “And that would eat up a feller like [umpire] Babe Pinelli. I said to the Babe, just ignore ’em, and he did and they stopped after awhile. Fans like you to growl back at ’ em.”

For the men in blue, ignoring “Three Blind Mice” is easier said than done. Goodding eventually stopped playing the song. The reason: A formal complaint from an umpire led the league office to tell her to cut it out.

Meanwhile, in the Midwest, legendary Chicago Stadium organist Al Melgard was earning a reputation as the Gladys Goodding of hockey. Often credited as the first to match music to the action on the ice, Melgard played “Clancy Lowered the Boom” when referee Francis “King” Clancy called a penalty and “Don’t Cry Joe” when an opposing coach argued a call. He’d also welcome referees onto the ice with “Three Blind Mice,” a practice that continued, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported in 1958, until then-NHL president Clarence Campbell “pleaded” with Melgard to stop playing the song because it “was bad for the morale of the referee and linesmen.”

While Gooding and Melgard heeded the warnings of their leagues, Vince Lascheid, the Pittsburgh Penguins’ organist from 1970 to 2003, preferred to live dangerously. Though the NHL ordered him to cut the song from his repertoire, he said he still snuck it in every now and then to “see what would happen.” Nothing ever did.

In the cases when an organist or, more commonly these days, a button-pushing intern does get heaved, the question of jurisdiction always comes up. And the answer is: Yes, they can do that. The PBUC’s umpire manual says, “Organists are not to play in a manner that will incite spectators to react in a negative fashion to umpires’ decisions” and stipulates that a violation “can result in the umpire dismissing the violator from his or her duties for the remainder of the game.” Counter to the minor-league law of the land, MLB’s official rules are less explicit. Though there’s no specific mention of music, they do grant umpires the “authority to order a player, coach, manager or club officer or employee to do or refrain from doing anything which affects the administering of these rules, and to enforce the prescribed penalties.” Think of it as baseball’s necessary and proper clause.

Just because umpires can eject rabble-rousers doesn’t mean they always do. O’Connor says sometimes a warning is all that’s called for. “You’ve got to handle the situation as it comes up,” he says, denying that there’s a strict rule for umps who hear those telltale tones. “Every situation is unique when you’re officiating.”

The trouble for umpires is that we only hear about it when they pitch a fit. Ignoring “Three Blind Mice” doesn’t warrant blog posts, sports radio segments, or mentions from Paul Harvey. But it’s worth saying that not all officials have skin as thin as a Pirates-era Barry Bonds. There are indeed umps who possess an unexpected ability to take a ribbing without retaliating. Or maybe there’s another explanation. Perhaps it’s just that their hearing is as bad as their eyesight.