David Griggs died in a car wreck while driving drunk. Rodney Culver died in the crash of ValuJet Flight 592. Doug Miller was struck by lightning. Curtis Whitley died of a drug overdose. Chris Mims died of an enlarged heart, Shawn Lee of cardiac arrest, and Lew Bush of a heart attack. And on Wednesday, 43-year-old Junior Seau became the eighth member of the 1994 San Diego Chargers to pass away before his 45th birthday. Police found Seau in his home, having reportedly shot himself in the chest. The day before, according to TMZ, he texted his ex-wife and kids to tell them he loved them.

The shocking death toll of that AFC-championship-winning squad can only be partly attributed to football—nobody dies in a commercial plane crash or gets hit by lightning because they played in the NFL. That tragic list is also a reminder that brain trauma isn’t the only risk that football players face: Mims, Lee, and Bush were all enormous men who succumbed to heart ailments.

But Seau’s apparent suicide will not be an occasion for a nuanced discussion about football and health. Instead, he will become a powerful symbol—the most-famous name in the disturbingly long rundown of NFL players who’ve taken their own lives. As the NFL has grown in popularity year after year, football fans have managed to put these deaths in the back of their minds, somewhere they won’t bother us when we’re rooting for our favorite teams. On April 19, ex-Falcons safety Ray Easterling killed himself after apparently suffering from depression and dementia for years. Easterling’s suicide was a tiny blip on the NFL wire, drowned out by tens of thousands of words about Andrew Luck and Robert Griffin III.

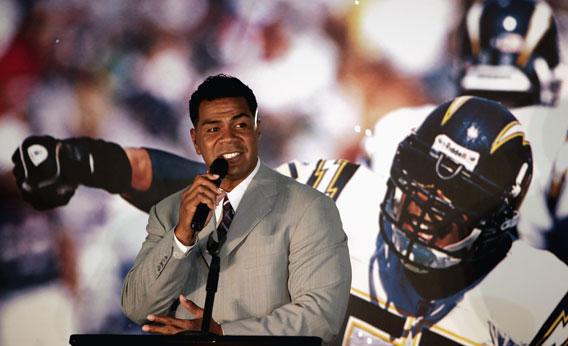

Seau’s death will be harder to set aside. Just five years ago, he was the personification of football toughness, a hard-hitting linebacker whose last name—which he capitalized on to create a Say-Ow clothing line—reflected what he did to quarterbacks. “When football players get dinged, they go back and play,” ex-New England Patriot Ted Johnson told the Lowell Sun in 2007. “You can see [Junior] Seau’s arm with the bone broke, ripped out of the skin. But you can’t see the damage of a concussion.” Seau, whose gruesome broken arm has been immortalized on YouTube, had no known history of concussions. But given the shaky reliability of NFL injury reports and the supposed dangers of sub-concussive trauma, everyone will surely ask if unseen brain damage caused Seau to shoot himself.

The method of Seau’s reported suicide—a gunshot to the chest—is also freighted with symbolism. Last year, ex-Bears safety Dave Duerson, like Seau, shot himself in the chest. In Duerson’s case, this was an intentional choice, designed to preserve his brain for study—his suicide note included a request that his family “see that my brain is given to the NFL’s brain bank.” A subsequent autopsy confirmed the diagnosis that Duerson suspected: His brain showed signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a disease that researchers believe is caused by repeated head injuries and is associated with depression and dementia.

Seau reportedly left no suicide note, so it’s as yet unclear whether he was explicitly following Duerson’s example, or whether he believed that football had damaged his brain beyond repair. Two years ago, Seau drove his car off a cliff shortly after getting arrested for allegedly assaulting his girlfriend. (He denied at the time that he was trying to kill himself.) After Seau’s arrest, concussion researcher Dr. Robert Cantu openly speculated that Seau might be suffering from CTE. “Nobody knows for sure,” said the Buffalo News story in which Cantu floated that theory. “Doctors cannot diagnose CTE in living people, leaving many unanswered questions until their deaths.”

The inevitable autopsy of Seau’s brain can’t answer every question about his suicide or his history of bad behavior. Along with that 2010 domestic violence allegation, he also allegedly threw drinks on a pair of women at a bar in 2007, telling one of them, “Get on a treadmill, you c–t.” In 2004, he also allegedly said that the best way to slow down LaDainian Tomlinson was to “give him a couple pieces of watermelon [and] load him up with some fried chicken.” Was that the CTE talking, or was Seau sometimes just a huge jerk? And what about Seau’s rough upbringing, the years when his dad beat him with a wooden paddle and he was menaced by drug dealers and gang members? Could those years, in addition to (or instead of) whatever trauma he might have suffered on the football field, have increased the odds that he’d commit suicide?

It’s likely that those sorts of distinctions won’t get much attention in the next days and weeks—the focus will be on whether Seau’s off-field behavior was the result of on-field injury. It’s perhaps unfair to speculate wildly that brain trauma was the root cause of the linebacker’s suicide. I also don’t believe there’s any good data on whether NFL players commit suicide more often than non-NFL-ers of the same age. But given the NFL’s history of ignoring the potential risks of concussions, it’s not a bad thing to see the pendulum swing so far in the other direction—for the death of a famous player to make NFL fans and Commissioner Roger Goodell stop and think about what they might be abetting.

It’s too early to tell why exactly Junior Seau killed himself, but it’s much too late to sit back and take a wait-and-see approach to how the NFL deals with head injuries. Ignore the NFL Draft. Ignore offseason mini-camps. Ignore the latest free agent signings. There’s only one thing worth talking about in pro football right now, and Junior Seau just reminded us what that is.