For a state of 3 million people, Arkansas has produced more than its share of basketball heroes. Sidney Moncrief, Scottie Pippen, Derek Fisher, and Joe Johnson have accrued 18 All-Star appearances and 11 NBA titles. As high-schoolers, however, none of them stacked up to Eddie Miles and Jackie Ridgle.

In the 1950s, Miles led North Little Rock’s all-black Scipio Jones High School to four straight state titles. “We called him ‘rocking chair’ because he would absolutely rock you,” one of his opponents told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette in 2002. “He could drop 50 on you whenever he wanted.” Ridgle, who was reputed to have a 40-inch vertical leap, regularly scored in the 30-point range in leading Altheimer’s Martin High School to its first all-black-schools state championship in 1966. But when you look at Arkansas’ official list of all-time leading high-school scorers, you won’t see Miles and Ridgle.

It’s not just Arkansas that omits the feats of black high-schoolers who played in segregated schools. In 1956, forward Hubert “Geese” Ausbie of Crescent, Okla., scored 186 points over three consecutive tournament games for all-black Douglas High School. Ausbie, who went on to play the role of the “Clown Prince of Basketball” for the Harlem Globetrotters, recalls averaging from 30 to 40 points a game as a high-schooler. Ausbie’s name, though, isn’t on Oklahoma’s all-time scoring list. (He tells me he should be near the top, in the neighborhood of supposed all-time leader Rotnei Clarke.) And Ausbie isn’t the only former Globetrotter who might be unfairly excluded from the record book. Other possibilities from Oklahoma alone include Marquis Haynes, who helped the Globetrotters defeat the NBA champion Minneapolis Lakers, and twins Lawrence and Lance Cudjoe.

These legends’ absence from the historical record—and their resulting exclusion from news stories about modern-day prep basketball stars—is a direct consequence of the Deep South’s segregationist past. Before the late 1960s, whites played against whites and blacks played against blacks. Arkansas, like many other states, separated its athletics associations by race. In 1967, what had been the all-white association incorporated its black counterpart, and what’s now the Arkansas Activities Association was born. This merger, though, was not accompanied by the integration of the state record book.

The high-school record keepers I contacted across the South appear open to correcting the record. Wadie Moore, the Arkansas Activities Association’s assistant executive director, is open to giving heretofore excluded black athletes their due so long as he can see documentation of their scoring marks. And after receiving my call, Moore says he now plans to email news outlets around Arkansas to ask for help with finding these records for other great pre-integration athletes.

Even for those with the best of intentions, finding documentation can be incredibly difficult. Kevin Farr, the content director for CoachesAid.com, the company that serves as the keeper of Oklahoma high-school stats, says he spent three years researching the state’s prep basketball history. Though he found proof that Ausbie scored 70 points in a single tournament game, Farr says tracking down regular-season stats for midcentury African-American players is a lot tougher. The problem is the lack of newspaper coverage afforded to all-black high schools.

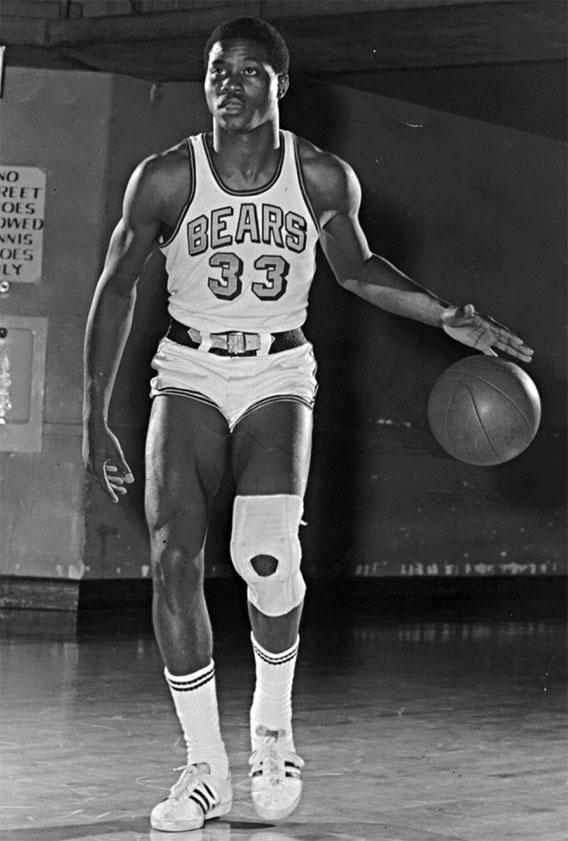

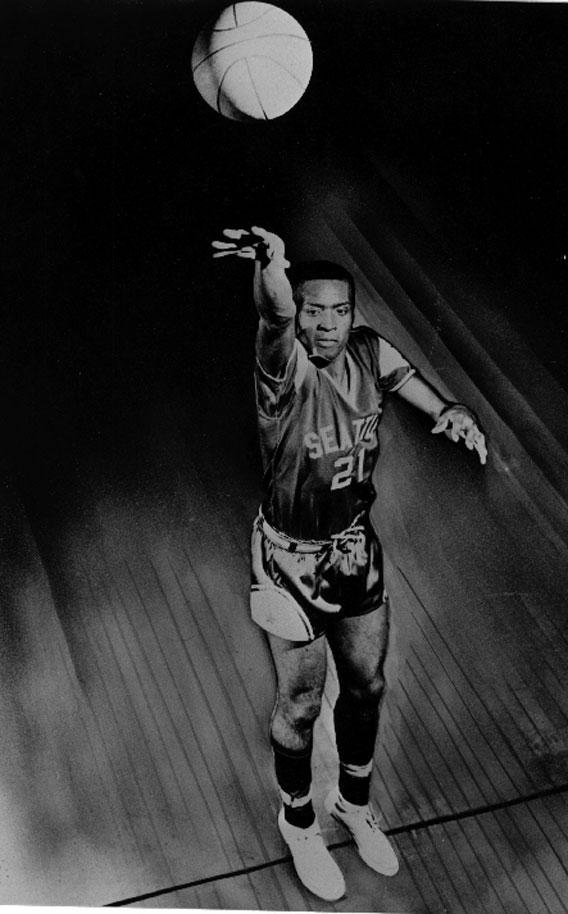

William “Sonny” Walker, who covered central Arkansas sports for the black newspaper the State Press in the 1950s, doesn’t recall seeing any Arkansas Gazette or Arkansas Democrat reporters at all-black schools’ athletic events. This lack of exposure didn’t keep stars like Ridgle and Miles from the collegiate big stage—the former averaged more than 30 points in his freshman season at UC-Berkeley, while the latter is the third-leading scorer at Seattle University—but the lack of contemporary record-keeping does make their athletic legacies more tenuous.

Courtesy Seattle University.

Nevertheless, some press clippings have survived. According to a State Press clip, Miles averaged 30.3 points in his junior season, and I’ve been told that a Pine Bluff Commercial photo caption pegs Ridgle’s senior-year scoring average at 29.7 points. These numbers should place both players in the Arkansas Activities Association’s top 10 for single-season scoring. I mailed the Arkansas State Press clip to Moore, the AAA’s record-keeper, and he said that should suffice for Miles’ inclusion. For Ridgle, he’ll accept the Pine Bluff Commercial clip but tracking that down won’t be easy. The Altheimer resident who recalls it doesn’t know its current location. It could possibly be found by scouring winter and spring 1967 microfilm of the Commercial, but getting to those archives may entail a trip to another county.

In some states, like Kentucky, more research has been done into pre-integration black athletes. Louis Stout, the first African-American in the nation to head a state athletic association, spent nine years putting together a 300-page book on Kentucky’s athletic league for black high schoolers. His research has helped pave entry into the state’s Hall of Fame for some pre-integration stars who otherwise would have been overlooked. But the difficulty in tracking down rock-solid documentation has made it difficult to revise Kentucky’s record book.

One record that should be included in the record book right now is the 65-game winning streak by Horse Cave Colored School in the 1940s. Horse Cave, a powerhouse African-American program, became the first school in Kentucky to produce seven all-state players, three of whom would play for the Globetrotters. Though the 65-game winning streak wasn’t accomplished under KHSAA auspices, it’s worthy of at least an asterisk in its official records.

More states in the South and Midwest should find places for researchers like Louis Stout. Diligent investigations of microfilm of black newspapers might not turn up every statistic of every notable player, but they will expand on the record of a woefully undocumented era.

With very few Louis Stouts to go around, most research is now undertaken by interested parties. Ron Lawson Jr., for instance, was determined to find news accounts of his father Ronald Lawson Sr., who led Nashville’s Pearl High School to two straight black national championships in 1958 and 1959. Lawson Jr. eventually found his father’s high school statistics in a Los Angeles Times article. (Lawson Sr. played at UCLA under John Wooden.) While impressive, Lawson Sr.’s junior and senior averages (around 28 points and 17 rebounds per game) don’t warrant inclusion into the Tennessee Secondary School Athletic Association’s record book. Still, his son’s investigations have helped expand his father’s legacy since his 2002 death, and Lawson Sr. gained passage to the TSSAA’s Hall of Fame in 2004.

Lawson Jr. says there are other pre-integration stars in Tennessee who haven’t gotten as much attention as his father. He hopes researching their careers brings them deserved recognition, preferably while they’re still alive. “I believe you need to smell your flowers when you’re above ground,” he says.

Miles and Ausbie, who are both still living, have both made the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame. Ridgle, who died in 1998, has not. These three basketball greats, like many of their contemporaries, get mentioned on plaques at community basketball courts or in special newspaper sections on black pioneers. But their exclusion from the record books means they’re excluded from mainstream media, which means that their names will be increasingly forgotten.

Major League Baseball doesn’t incorporate numbers from the Negro Leagues into its accounts of all-time leaders. But MLB doesn’t purport that its statistics represent the total history of baseball in the United States. When states proffer lists of record holders, by contrast, every effort should be made to ensure that those lists are complete. At minimum, state activities associations need to make sure their press releases mention that the official records exclude many deserving black players. As players like Eddie Miles and Geese Ausbie wait to get their due, we should at least acknowledge that they’ve been forgotten.