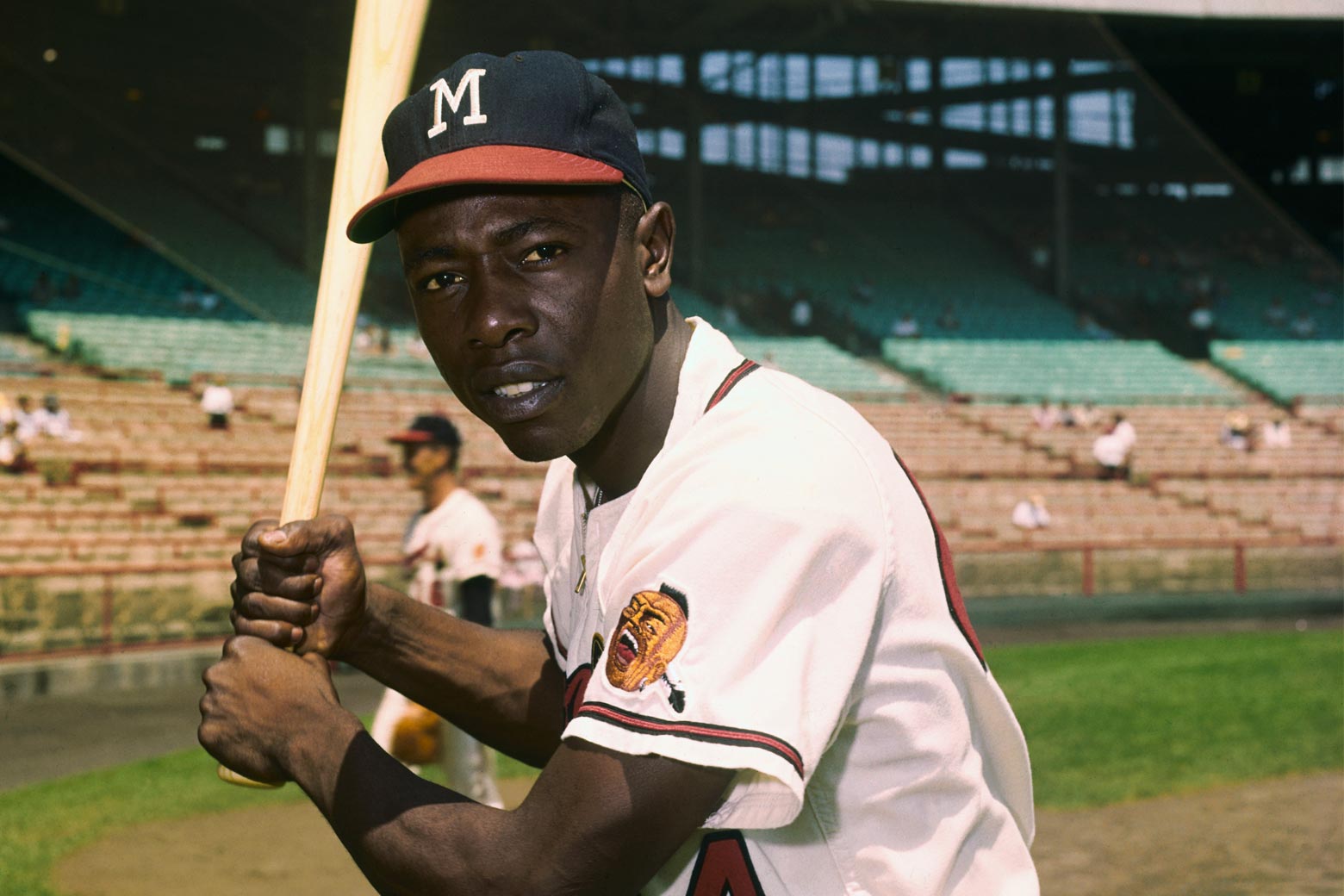

Baseball legend Hank Aaron died on Friday. Slate is republishing this 2007 story on the media’s treatment of the former home run king.

This baseball season, it fell to the sporting press to drag a reluctant Hank Aaron once more into public view, the occasion being Barry Bonds’ slow-motion pursuit of a stationary number. Now, any time an old baseball personage hobbles back into frame, he is invariably described in awed, petrifying language better suited to, say, the Archbishop of Canterbury. The treatment of Aaron hasn’t been any different. A spin through the sports pages over the past few months reveals that he is a man of “cool dignity,” “quiet dignity,” “innate dignity,” “immense dignity,” “eternal dignity,” “unfettered dignity,” “unimpeachable dignity,” the very “picture of dignity” who “brought so much dignity to baseball” and who, “having exuded dignity his entire life,” continues to this day “exud[ing] class and dignity.” Aaron, proclaimed the inevitable George Will, who perhaps learned about dignity from selling his to Conrad Black, was “The Dignified Slugger From Mobile.”

No one would quibble with the sentiment, unctuous and condescending though it may be. Aaron’s forbearance was indeed remarkable; in many ways, he holds up better in history’s eyes than the peer to whom he is often compared, Jackie Robinson—himself a “pillar of dignity”—whose outspokenness regrettably extended to the odd HUAC hearing and Nixon campaign stop.

No, what’s unfortunate about Aaron’s latest turn in the public eye is that he has been reduced to a sportswriter’s cheap trope. The great slugger’s dignity is of interest only insofar as it can be picked up by the likes of George Will and swung in the general direction of Barry Bonds. (As of Friday morning, Bonds stands just two home runs shy of Aaron’s 755.) “As Barry Bonds continues his gimpy, joyless pursuit of such glory as he is eligible for,” Will wrote, “consider the odyssey of Mobile’s greatest native son.” Or as a Cincinnati Post headline pronounced: “Safe To Say Bonds No Aaron.” Of course, with Aaron, it has always been thus. It is the singular curse of his career: to be treated like a sandwich board for the prevailing attitudes of the day.

It was uglier a half-century ago. Aaron hit the majors in 1954, after a stint in the Negro Leagues and a year with the Milwaukee Braves’ affiliate in the South Atlantic League, which he helped integrate. As baseball historian Jules Tygiel points out, his timing was impeccable—Aaron was one of the first black ballplayers whose career unfolded more or less naturally, without segregation or war chipping away at his prime.

Once in the bigs, he quickly became, as a comically obtuse 1958 New York Times Magazine profile put it, “a symbol of a new era of slugging,” a savage of preternatural talent. (The headline: “The Panther at the Plate.”) “Aaron brings to baseball an atavistic … single-mindedness,” William Barry Furlong wrote, going on to describe the “somniferous-looking” Aaron’s “insouciance” and “indolence” and taking care to twice point out his “shuffling” gait. No mention was made of Aaron’s thorough preparation, before which even Ted Williams salaamed. The Times was far from the only offender. Even Aaron’s first manager, Charlie Grimm, went in for this nonsense. He liked to call Aaron “Stepin Fetchit.”

Some of this was surely a product of Aaron’s shy and unadorned personality at the time, which offered the media little but a bare armature on which to shape whatever they wished. He didn’t have Willie Mays’ élan; his hat didn’t whip off whenever he rounded second. He drove a Chevy Caprice. “Grace in a gray flannel suit,” one writer called him.

Likewise, Aaron’s performance over 23 seasons—consistently very good, occasionally great, always a notch or two below Mays’—lacked the dizzying peaks that give a career the flavor of personality. He never hit more than 47 home runs in a year, never hit better than .355, never had an on-base percentage higher than .410.

Because he was so outwardly bland in personality and performance, Aaron seemed to take on character only in relation to things people felt strongly about: Willie Mays, Babe Ruth, civil rights. On his own he was, and remains, an abstraction, someone whom writers could only explicate with banalities like “dignified.” Our perception of Aaron today stems almost entirely from his pursuit of Ruth’s 714 home runs, in 1973 and 1974, during which time he faced down an assortment of death threats and hate mail. By then, Aaron had shed his reticence and begun to speak out against baseball’s glacial progress on matters of race. Still, very much his own man, he seemed to dismiss some of the loftier interpretations attached to his home-run chase. “The most basic motivation,” he wrote in his autobiography, I Had a Hammer, with Lonnie Wheeler, “was the pure ambition to break such an important and long-standing barrier. Along with that would come the recognition that I thought was long overdue me: I would be out of the shadows.”

No matter. Aaron was fashioned into something of a civil rights martyr anyway. “He hammered out home runs in the name of social progress,” Wheeler recently wrote in the Cincinnati Post. And Tom Stanton, in the optimistically titled Hank Aaron and the Home Run That Changed America, dropped what has to be the most unlikely Hank Aaron analogy on record: “[P]erhaps it’s TheExorcist, the period’s biggest movie, that provides a better metaphor for Hank Aaron’s trial. … Hank Aaron lured America’s ugly demons into the light, revealing them to those who imagined them a thing of the past, and in doing so helped exorcise some of them. His ordeal provided a vivid, personal lesson for a generation of children: Racism is wrong.”

Small wonder that, upon eclipsing Ruth, the exorcist told the crowd, “I’d just like to thank God it’s over.”

Now here is Aaron, once again, this time in the midst of the galloping national hysteria over anabolic steroids. In Aaron, we have our cardboard hero, propped up in the corner to stand in exquisite counterpoint to Bonds. He is not the only one dragooned into this particular mess—”Ryan Howard, No Asterisk,” went one preseason headline—but it is most certainly Aaron who is shouldering the psychic load. Even the flatness of his career, strangely, now earns him praise.

“[N]ot one of Aaron’s single-season home run totals is among the 68 highest of all time, yet he pounded more in his career than any other player in history—and without suspicion of chemical enhancement,” wrote Tom Verducci in this week’s Sports Illustrated cover story, blithely sidestepping the very real possibility that Aaron popped amphetamines like Chiclets along with, you know, everyone else in baseball. To even consider that would, of course, call into question a rather large piece of the argument in favor of baseball’s current war on steroids—Maintain the sanctity of the record books! Ferret out the cheats!—something sportswriters evidently have little interest in doing. Instead, they summon a hero from the past to redress the supposed sins of the present. “I guess,” Reggie Jackson told Verducci, “you can call him the people’s home run king.”

Our national celebration of Aaron is, fundamentally, childish stuff. This is baseball telling fairy tales to itself, pretending the bad things away, using a Hall of Famer as a rhetorical bludgeon and in doing so diminishing the very man it pretends to exalt. There is a word for that. Undignified.