The Longform.org Guide to NBA Legends

Six amazing stories about the lives of great basketball players, on the court and off.

Every weekend, Longform.org shares a collection of great stories from its archive with Slate. For daily picks of new and classic nonfiction, check out Longform.org or follow @longformorg on Twitter.

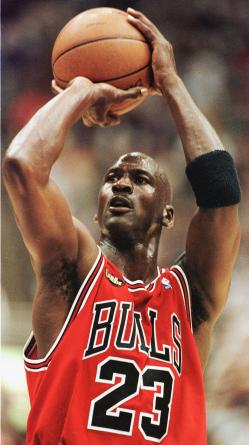

AFP/Getty Images

The NBA is back! Well, it’s almost back. The shortened season will tip off Christmas Day, when LeBron, Kobe, and the rest of the league’s biggest names finally take the court. It’s no surprise that David Stern is putting those guys front and center. While many of the stickiest points in this fall’s lockout negotiations concerned journeyman players, the NBA has always been a star-driven enterprise. So, in that spirit and to tide you over until Dec. 25, here are five of our favorite articles about some of the best players in the history of the NBA—and one about a guy who could have been on that list, but became a legend for another reason.

David Halberstam • The New Yorker • December 1998

On one of the great final acts in sports history:

“Michael Jordan was thirty-five, and arguably the dominant athlete in American sports, as he led Chicago into Salt Lake City. He was nearing the end of his career, and he was, if anything, a more complete player than ever. What his body could no longer accomplish in terms of pure physical ability he could compensate for with his shrewd knowledge of both the game and the opposing players. Nothing was wasted. There was a new quality, almost an iciness, to the way he played now. In 1995, after Jordan returned to basketball from his year-and-a-half-long baseball sabbatical, he spent the summer in Hollywood making the movie Space Jam, but he demanded that the producers build a basketball court where he could work out every day. Old friends dropping by the Warner lot noticed that he was working particularly hard on a shot that was already a minor part of his repertoire but which he was now making a signature shot––a jumper where he held the ball, faked a move to the basket, and then, at the last minute, when he finally jumped, fell back slightly, giving himself almost perfect separation from the defensive player. Because of his jumping ability and his threat to drive, that shot was virtually unguardable. More, it was a very smart player’s concession to the changes in his body wrought by time, and it signified that he was entering a new stage in his career. What professional basketball men were now seeing was something that had been partly masked earlier in his career by his singular physical ability and the artistry of what he did, and that something was a consuming passion not just to excel but to dominate. ‘He wants to cut your heart out and then show it to you,’ his former coach Doug Collins said. ‘He’s Hannibal Lecter,’ Bob Ryan, the Boston Globe’s expert basketball writer, said. When a television reporter asked the Bulls’ center, Luc Longley, for a one-word description of Jordan, Longley’s response was ‘Predator.’ ”

Tony Kornheiser • Sports Illustrated • April 1983

On the self-inflicted torture of Rick Barry:

"In sum, Barry was so good that he awed people. But he was so uncompromising that he antagonized them, too. He couldn't understand why the game didn't come as easily to others as it did to him. And for 15 years, in the NBA, the ABA, and on CBS he told them so—in private, in public and in no uncertain terms. He had no patience for mistakes, no tolerance for mediocrity. ‘He was such a perfectionist,’ says Butch Beard, who played with and against Barry. ‘He wanted the game to be perfect. And when it wasn't, he would jump all over you. He didn't mean it maliciously, but it could be very intimidating.’ Barry excused his behavior by telling teammates that as hard as he was on them, he was harder still on himself, but some didn't buy it. ‘He had a bad attitude. He was always looking down at you,’ says the Celtics' Robert Parish, an erstwhile Warrior teammate of Barry's. ‘He was the same on TV,’ says the Sonics' Phil Smith, another former Warrior. ‘He was so critical of everyone. Like he was Mr. Perfect.’

“Instead of being cheered by his peers as the pioneer whose jump from the NBA to the ABA in 1967 precipitated the salary explosion, Barry has been roundly decried for being self-absorbed and petulant. Yet no one who followed his lead—most notably the sainted Julius Erving, who attempted to jump to the NBA Atlanta Hawks in 1972 while still under contract to the ABA Virginia Squires—received anything but the mildest public reproach. And Barry, who many experts think is one of the two best forwards in NBA history—the other being Baylor—hasn't gotten full credit because of his abrasive behavior."

Woody Allen • Sport • November 1977

On the brilliance, and elusiveness, of the great Knicks point guard:

"It’s amazing, because the audience’s ‘high’ originates inside Monroe and seems to emerge over his exterior. He creates a sense of danger in the arena and yet has enough wit in his style to bring off funny ideas when he wants to. He has, as an athlete-performer, what few actors possess. Marlon Brando is one such actor. The audience never knows what will happen next and the potential for a sudden great thrill is always present. If we think of an actor like George C. Scott, for instance, we feel he is consistently first rate, but he cannot move a crowd the way Brando does. There is something indescribable in Brando that pins an audience on the edge of its seats at all times. Perhaps because we sense a possible peak experience at any given moment, and when it occurs, the performance transcends mere acting and soars into the sublime. On a basketball court, Monroe does this to spectators."

Gilbert Rogin • Sports Illustrated • November 1963

The most successful player in league history, Bill Russell, was also its most candid:

“Russell's scraggly beard is a telling indication of the man. Not only is Russell nearly 6 feet 10 and black—circumstances, obviously, over which he has no control—but he has deliberately set himself further apart by being one of the few professional athletes to wear a beard. Ask him why he grew it and he will reply in time, if he feels like it: "I've thought about it, and I've thought about it. Why did I wear the beard, why do I? It's part of this thing—I've always fought so hard to be different and I am different without even trying, and maybe it's just my own little revolution. It just isn't done in polite circles, in a sense. But I do think it's part of my personality. When I first joined the Celtics I shaved the beard off. I did it on my own. It was none of their business, and if I had valued their opinion I would have asked them. I made a concession to conformity at that time. Then I grew it back. After we won the first championship I let Heinsohn shave it off, and then I grew it back again. It was a very childish thing, in the sense of defiance. I wear it now to let people know I am an individual. I do think for myself, and I'm very opinionated. Contrary to popular belief, I'm a living, thinking, breathing human being."

Mike Sager • Esquire • November 2007

A rare glimpse of Kobe Bryant’s nonstaged private life:

"Now, in the gym, the ball arcs perfectly through the rim and ripples the bottom of the net with a distinctive, thrilling swish. The moment is unfrozen; time moves on. Kobe nods his head once, almost imperceptibly, as if to say, That's what I'm talkin' about, an expression he uses with exuberance when he's in private, when something catches his fancy, when something he believes is borne out. A picture of Kobe seldom seen: his perfect white teeth bared in the large carefree smile of a young man who loves watermelon and those yummy ice cream Kahlúa drinks he and his wife had the other night for dessert at the restaurant in Las Vegas before seeing the show Kà, and who is lately in love with the Harry Potter series, which he read at a breakneck pace, trying to beat out his wife, the first books he's read since twelfth grade, when he became obsessed with the sci-fi thriller Ender's Game, about a boy who suffers greatly from isolation and rivalry but ultimately saves the planet."

Rafe Bartholomew • Deadspin • June 2010

The story of Billy Ray Bates, who had the talent to be an all-time great, but drank himself out of the league and ended up playing in the Philippines, where he had a few wild years before booze ended his career for good:

"Bates was 32, and in the six years since he first played in the Philippines, he must have put 15 years' worth of mileage on his body. His coach made him promise not to drink and party too much, but the import couldn't resist the temptations of Manila nightlife. At Añejo, Bates still averaged a respectable 31 points, but the team lost its first four games, and Bates looked like a shell of his former self. When fans saw him struggling to defend rookie guards and getting his shots blocked by local forwards, they saw the Black Superman cut down to size. Bates was spared the biggest embarrassment of his career the night of his final PBA game. He scored a career-low 17 points and looked helpless against younger, healthier competition, but few people witnessed the game because a violent storm caused a blackout in Manila. It was as if fate had intervened to prevent television audiences from seeing Bates at his humiliating nadir."

Have a favorite piece that we missed? Leave the link in the comments or tweet it to @longformorg. For more great sports writing, check out Longform.org's complete archive.