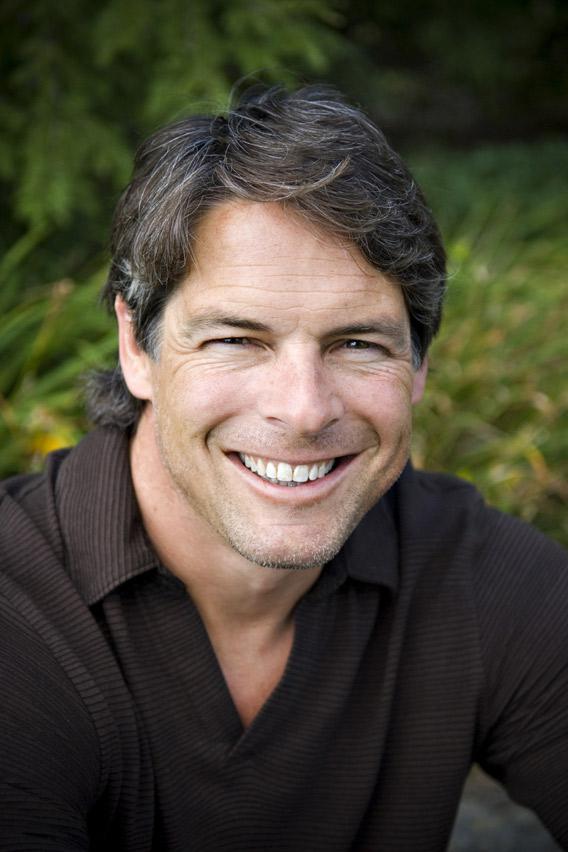

Styled “the Renaissance Man of Sports” by both the Los Angeles Times and Sports Illustrated, Tim Green does everything but play the lyre. He shone on the football field at Syracuse University, earning All-American honors, before joining the Atlanta Falcons as a defensive end. During Year 2 of his NFL career, he enrolled in law school and began a novel, the first of 26. “Sports is a proving ground for what happens over the rest of your life,” he says. Now a father of five, Green has analyzed professional football at Fox Sports and served as a commentator for Good Morning America and NPR. He’ll fly his athletic and intellectual colors on May 8 at the next Slate/Intelligence Squared live debate in New York City, where he and sports columnist Jason Whitlock will dispute the motion, supported by Malcolm Gladwell and Buzz Bissinger, that college football should be banned.

Green makes an emotional appeal for the sport, arguing that it creates habits and knowledge that benefit players for the rest of their lives. He returns to perseverance, team work, and discipline as beacon values instilled by football. Green’s challenge at the debate may be squaring his own rewarding experience as an athlete with evidence of NCAA corruption and medical risk. Here are excerpts of our recent conversation.

Slate: Could you talk about your experience as a college football player? What are the similarities and differences between playing in the NCAA and the NFL?

Tim Green: I loved playing football in college. I had a great experience as a student-athlete. The difference between college and the National Football League is pretty intense. Everyone is bigger, faster, stronger—and it’s a lot more vicious and violent.

Slate: Did you find yourself having to choose between sports and academics at Syracuse?

Green: No. I enjoyed my academic experience as much as I enjoyed my athletic experience. The only thing that I fell short on is I probably didn’t get to drink quite as much beer as other people. The level of success that I was able to have in both arenas makes it evident that I did have enough time.

Slate: Is there anything you would have done differently during college, in terms of balancing your priorities?

Green: No. I really felt like I had achieved a good balance between the two. I enjoyed the dichotomy of sports and academics, which is why I went to law school when I was a pro player. And honestly, I think that if you can do both, each one makes the other more pleasurable, since they are quite different. The common factor is a lot of tireless work when no one is cheering for you. But I felt that going from one to the other made me appreciate each one more.

Slate: What’s the primary mission of a university?

Green: The primary mission is academics. That said, the lessons you learn on the playing field can be extremely valuable. The problem is when people fail to translate those lessons. Teamwork, hard work, discipline, perseverance—they’re all well and good, but you’re missing out on most of football’s benefits if you can’t take those things and apply them to your post-athletic career.

Slate: How has being an athlete enhanced other aspects of your life?

Green: I understand the value of hard work and a lot of it. I grasp that life, like an athletic competition, has twists and turns that aren’t always fair, and that the best way to deal with those things is to put them behind you and play on. Teamwork is another thing. You have to count on others. You learn that you’re not always going to love everyone on your team. But people can still provide value to a team and still help you achieve a common goal. They don’t have to be your best friend.

Slate: Have you seen the research connecting football to brain injury?

Green: Yes. From what I’ve gathered, it’s all anecdotal. No one has come up with conclusive evidence. There are suggestions of long-term effects, and in fact they may be true, but so far I don’t see any proof. The most compelling evidence that’s been brought to light so far deals with NFL players. And anyone that suggests college football reaches the same levels of intensity as the National Football League, well, that person just hasn’t experienced both college and pro football.

Slate: Jerry Sandusky at Penn State. Out-of-control boosterism at the University of Miami. Academic fraud and unethical dealings between assistant coaches and NFL agents at the University of North Carolina. Why has college football been wracked by so many scandals recently? Is there some kind of common denominator?

Green: Whenever there’s a tremendous amount of money involved in something—whether it’s medical research or food programs for Third World countries or presidential politics—you’ll find people who behave badly. But those people are the exception, not the rule.

Slate: Is there too much money in the college football business to serve players’ best interests?

Green: I believe in the free market economy and capitalism. It’s what this country was built on. College football earns money because it has entertainment value: It’s like a movie that you perhaps personally find silly or absurd, but it rakes in $200 million at the box office. For whatever reason, football fills a void in people’s lives—they enjoy it and flock to it. That’s just our world. I don’t begrudge people the way they spend their money on entertainment and I certainly don’t begrudge the entertainers.

Slate: So should college football players be paid, like other entertainers?

Green: Yes. For one, it would reward them for their significant efforts. Also, it would diffuse some of the excesses and corruptions you spoke of. You’ll never completely eliminate them, because we’re human beings and we’re flawed. But I think it would serve to at least lessen those temptations.

Slate: What about separating teams from schools?

Green: I don’t think that will ever happen. I certainly agree that college football and college basketball are farm teams for the NBA and the NFL. What you have, though, is tradition and a connection between student-athletes and the other students and the alumni that’s very powerful. You could argue that most athletes are there for the sole purpose of their sport rather than their education—although I think we’ve come quite a ways in the last 25 years, since I was in college. Graduation rates have improved. NCAA academic standards have gotten more stringent. Practice times have been reduced, all with an eye to educating student athletes.

Slate: The shortened practice times and firmed-up academic standards—are these good things?

Green: In some instances, yes. In others, athletes are being denied an opportunity. Because the NCAA has a monopoly on these pre-professional sports, it’s wrong to deprive people of the chance to make a lucrative athletic career just because they don’t have certain academic credentials.

It’s a paradox. As I said, there’s an unfairness to young athletes who are denied the opportunity to play in farm leagues because of their lack of academic success. But if colleges are not going to relinquish control of these leagues, which they’re not, it only makes sense that they should do their best to foster this idea that athletes should be students as well. That means getting their degrees and being a legitimate part of the student body. And the NCAA has done that. You see, they have stiffened the requirements for players coming out of high school. They’ve tightened them during a player’s college career. And they’ve also reduced, by mandate, the amount of time that an athlete can spend with his coaches and on the practice field. All those things equate to a higher probability that an athlete is also going to be a student—that he’ll leave with a college diploma. And I think that’s good, if only because I can’t see the NCAA or colleges ever saying, you know what, we’re just going to relinquish this multibillion-dollar revenue stream because it doesn’t have a place in our institutions of higher learning.

Slate: Some people complain that football players at major programs can get away with academic problems that normal students would be punished for. On the other hand, fans and coaches say that players’ relative prominence means they’re on the hook for the most minor infractions. What do you think happens more—athletes being held to higher or lower standards than the general student population?

Green: It’s a bell curve: On one edge, players get away with things because they’re players. On the other edge, players’ celebrity puts them under heightened scrutiny. I think the majority lies right in the middle with the rest of the students. That’s my perception of it. Of course, whenever a player does get away with something that he shouldn’t, that excites the attention of the media and gossip and Facebook and Twitter.

Slate: You’re playing defense at this debate. When Buzz Bissinger and Malcolm Gladwell attack college football, what will you say redeems it? In what sense does the good outweigh the bad?

Green: I am thankful for my great experience as a college athlete and I would hate to see other athletes denied that opportunity. There are a lot of good things about college sports. They’re not without their flaws, just like anything else. But on the whole, football was something that I dreamed of as a kid—something that I was and am very grateful that I was able to do. To me, the notion that people would be denied that opportunity is unthinkable.

Finally, a word of caution: I know the game has evolved to become more safe than it was before. I think there’s a fine line between safety and diluting the excitement and intensity of the contest.