This piece is adapted from The End of The Perfect 10 by Dvora Meyers, published by Touchstone, a division of Simon and Schuster, Inc.

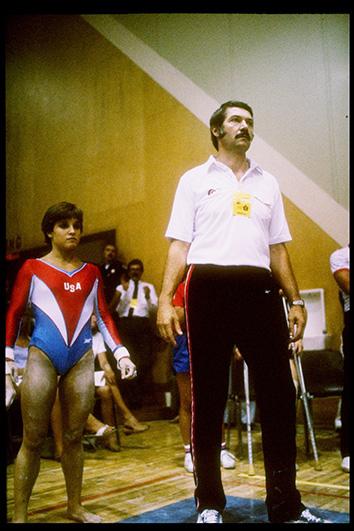

When Bela and Martha Karolyi defected from Romania and set up shop in Houston, it seemed like every high-level gymnast in the country landed on their doorstep. First, there was Dianne Durham, the 1981 junior national champion, who moved to Texas to train with the famed coaching duo. The next year, she won the 1982 junior title, which was followed by the 1983 senior national title, becoming the first African American woman to earn the top ranking in U.S. gymnastics.

Then there was Mary Lou Retton, a powerful sprite from West Virginia who went to the Karolyis at age 14 in 1982, just two years shy of what would be “her” Olympic Games in Los Angeles. And then in 1984, during the Olympic year itself, Julianne McNamara transferred to the Karolyis’ facility. By then, McNamara was already quite established as one of the best gymnasts in the United States—she had been named to the 1980 Olympic team at just 14 but did not compete due to the American boycott of the Moscow Games.

A lot has changed in the three decades since the Karolyis hung up their shingle in the United States. After the dissolution of the former Soviet Union, many of the gymnastics “brain trusts” in those countries migrated from the Eastern bloc to the West in the 1990s and set up their own shops, just as the Romanians had done in the 1980s. For a gymnast who aspires to train and compete at the highest levels, there are now many more gyms to choose from than in Mary Lou Retton’s day. Many gymnasts don’t even have to leave home to receive top-notch training, whereas in previous generations, moving to find a top gym or coach was a near certainty.

Tony Duffy/Allsport

And yet, the best gymnasts in the United States are still landing on the Karolyis’ doorstep. Every month since late 1999, young Olympic hopefuls have journeyed down to the Sam Houston National Forest in Texas, just outside of Huntsville—or New Waverly, depending on your map—for national team training camps run by Martha Karolyi at the Karolyi Ranch, which has been officially designated a U.S. Olympic Committee training site.

Bela Karolyi, who has retired thrice—first in 1992, and again in 1996, and yet again in 2000—is sort of like Jay-Z: He’s never done when he says he’s done. And Martha is the Beyoncé to his Jay—today, she is more relevant than ever.

The way most people tell it, the story of American women’s gymnastics has a before and after: Before the Karolyis and After the Karolyis. BK and AK, if you will.

BK, the story goes, the Americans were not good at gymnastics. Their gymnasts didn’t work hard, they weren’t fit, and that’s why they didn’t win any medals.

AK, the Americans became an unstoppable force, with Retton winning the all-around title at the 1984 Games, which the Soviets boycotted, and Kim Zmeskal winning the gold at the 1991 World Championships. According to most histories of U.S. women’s gymnastics, the Karolyis have been the engine driving most of the Americans’ success. But the American story in women’s gymnastics is a little more complicated than that.

First, the Americans were getting better at gymnastics before the Karolyis defected, even if their results internationally didn’t always bear that out. American gymnasts were routinely discriminated against by panels of Eastern bloc judges allied against the United States in the 1960s and early 1970s. By the late 1970s, however, American male and female gymnasts were starting to gain international attention. In 1978, Marcia Frederick won the world title on the uneven bars, while Kathy Johnson picked up a bronze medal on floor exercise at the World Championships in Strasbourg, France, with a lyrical style that rivaled the balletic Soviets. In 1981, Tracee Talavera won a bronze on the balance beam in the most hostile territory—Moscow. And in 1980, the United States fielded a wildly talented team featuring Johnson, Frederick, and newcomers such as Talavera, McNamara, and Beth Kline. This squad could have made its mark at the Olympics in Moscow had President Jimmy Carter not boycotted those games in protest of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

All of this is to say that the Americans were getting good—not dominant, but good—BK. The Karolyis weren’t exactly wandering into a gymnastics wasteland when they opened up their first gym in Houston in 1982. Their almost-immediate success in the United States proves that: No coach, regardless of ability, can build a national champion in less than a year. That Durham, who was already very successful at the junior level, won the senior national title in 1983, less than a year after moving to Houston to train with the Karolyis, is as much a testament to her previous coaches’ efforts as it was to the genius of the newly arrived Romanians. With their early athletes in the United States, the Karolyis were building on foundations laid by coaches who never became household names.

Even so, it’s inarguable that the Karolyis changed American gymnastics forever. While there were good coaches and good gymnasts in the United States when they arrived, there wasn’t an expectation of success. The Karolyis, fresh off their victories with Nadia Comaneci and the rest of the Romanian squad, made Americans believe that they could and should be winning. (They also were pretty good at spotting trends, predicting the era of the power gymnast, the one we’re currently living in, 30 years early.)

The few medal-free years after their second retirement in 1996 certainly made it seem like the Karolyis were inextricably bound up in U.S. gymnastics success. Terry Walker, a U.S. coach who currently works at World Champions Centre, believed as much. “The problem was Martha and Bela had retired and we didn’t have anybody pushing us,” he said of the 1997–2000 quadrennium. “There wasn’t a driving force.”

The Americans’ subsequent success in the 21st century has been credited in large part to the semicentralized national team training camp system that was introduced in late 1999. This system was heralded as something new, a melting pot approach—combining the Eastern way of centralization with the American tradition of independent gyms. But this idea wasn’t American at all: It dated all the way back to the 1970s, if not earlier, and it came from the Eastern bloc.

In the ’70s, Helmut Gerschau, a coach in East Germany, described the small nation’s gymnastics training system, second only to the Soviets’ at the time, to International Gymnast. He said he was one of four head coaches, one for each of the primary gymnastics training centers. Ten times a year, all of the coaches and best gymnasts were brought together to ensure they all “pull in the same direction.” It also gave gymnasts the opportunity to work with other coaches and get used to their techniques.

Since 1999, the Americans have experimented with a version of the East German system, with selected athletes (and their coaches) attending monthly national team training camps at the Karolyi Ranch. It’s not just the system organization that is imported from the former Eastern bloc gymnastics powers: The majority of the coaching talent has also been imported from abroad. In addition to the Karolyis, there is Valeri Liukin, a 1988 Olympic gold medalist for the USSR who owns two gyms in the Dallas area and is in charge of the developmental programs in USA Gymnastics. (He is also father and coach to 2008 Olympic gold medalist Nastia Liukin.) Liang Chow, a former member of the Chinese national team, coached Shawn Johnson and Gabrielle Douglas to Olympic gold medals. Mihai and Sylvia Brestyan emigrated from Romania and started a gym outside of Boston, where they coached Alicia Sacramone and Aly Raisman to world and Olympic titles.

Overseeing this large system of camps and coaching personalities is Martha Karolyi. She has been the national team coordinator since 2001, when her more famous husband stepped aside. (Or was forced out, depending on who is telling the story.) At times, NBC has made Martha, not the gymnasts, the star of its domestic gymnastics coverage. The commentators frequently wonder on air about what Martha is thinking—Who does she like? Whom will she choose for the team? During training sessions at major national competitions, the media and spectators pay nearly as much attention to Karolyi observing the gymnasts as they do the gymnasts themselves. I can’t say that I blame them: For some reason, watching a 70-something Romanian immigrant in a warmup suit move briskly around the competition floor as though she were part of a morning walk with Jewish seniors in Boca Raton, Florida, is oddly compelling.

Simon and Schuster

But the reason this system works is that Martha Karolyi does not act alone. There’s an ever-increasing number of homegrown coaches bringing talent up the ranks. And that is also due, in large part, to the training camp system.

Every month, when a select number of gymnasts—national team members and some other promising gymnasts—are invited to the Karolyi Ranch, their coaches accompany them to Texas, where they are able to exchange information with other, often more experienced, instructors. Mary Lee Tracy, assistant coach of the 1996 Olympic team and personal coach to gold medalists Amanda Borden and Jaycie Phelps, spoke about how much easier it is to learn today than when she was coming up. “When I was in their position at their age, it wasn’t like this,” she said. “You had to search and beg for information. Now, it’s at your fingertips. And everyone is more welcoming.”

Back then, it fell to just one or two coaches to figure out everything a talented gymnast needed to compete on the world stage—from drills to progressions to training plans to competition schedules. “Before, it was all up to the individual coach to get the kid where they need to go,” Wendy Bruce, a 1992 Olympic bronze medalist, pointed out. “It was on Rita and Kevin [Brown] to produce me. They didn’t have a lot of help, nor did they ask for a lot of help, nor did they bring anyone in.”

Part of the reluctance to bring someone in to help had to do with the very reasonable fear that this new coach might take the athlete with him or her. During Bruce’s career, “gym hopping” was rampant, and coaches tried desperately to hold on to the gymnasts they had spent years developing. If possession is 9/10 of the law, then the coach who walks into the Olympic arena with a gymnast owns more than 9/10 of the credit. As far as the media and sponsors are concerned, the previous coaches are unimportant.

Unlike in the bad old days, when coaches were worried about losing their athletes to more established programs and instructors, the current system encourages gymnasts to stay put. “They’re telling [the gymnasts] to stay and ‘We’ll help you where you are.’ That’s what Martha told me—they want to build a lot of clubs,” said Kelly Manjak, a Canadian who coaches several top NCAA gymnasts and Canadian national team members. The increasing number of clubs and coaches acts as an enormous dragnet on talent, helping USA Gymnastics find that rare prodigy who will become an Olympic champion.

Maddie Meyer/Getty Images

Simone Biles’ coach agreed that today’s setup made it possible for her to tutor a world-class gymnast. “I just got an incredible amount of education from the national staff,” Aimee Boorman said. “They see Simone, they see her talent, and they know that I didn’t have the tools necessarily to get her where she needed to be. So instead of saying, ‘Simone, you need to go to another gym,’ they said, ‘Aimee, we’re going to teach you how to get her where she needs to be.’ I will forever be grateful for that because now I feel like I am a coach of a world champion, not like I was somebody who had talent that I let slip away because I was too afraid to get my hands in there and work for it.”

This division of labor—with the national team staff in charge of management and strategy and the personal coaches responsible for developing athletes—is a boon to a coach like Boorman, who has to focus only on her athlete; she is not responsible for larger, strategic decisions.

Though the coaches and athletes put a very positive spin on the Karolyis’ training camps, former team doctor and trainer Larry Nassar admitted that in the early days they could be quite rough. First, there were the living conditions. “The gymnasts were quartered in these rustic rooms compared to what they have now,” he said. (Hilton, a corporate sponsor of USA Gymnastics, has revamped the cabins where the national team gymnasts bunk.) “The social break room was in the middle room where the coaches were at,” he added. “We’re trying to work out their injuries while the coaches and judges are sitting there playing cards and drinking beer and wine.” To expect the gymnasts to relax in this setting, surrounded by the very coaches who had been drilling them just 30 minutes before, was ludicrous. The athletes now have their own break room apart from the coaches and other adults.

There were also troubles with food at the early camps. “The kids’ luggage would get checked for food in the past. Many coaches did that,” Nassar said. “That doesn’t happen anymore because we’ve changed that culture. We have seen that by educating the kids and placing trust in them, giving them a greater sense of self-responsibility, most of the time, they will do the right things.” And it’s not as if the gymnasts don’t understand that their diet and weight are important components to athletic success. They’re tested on their physical abilities at the start of every camp. “By physical abilities, we can see if they’re out of shape,” he said.

Dr. William Sands, a sports scientist and former elite gymnastics coach, noted that the United States had changed its gymnastics culture to one that’s fanatical about conditioning. “They’re strong enough now to do what you ask them to do. You don’t have to rely on adrenaline,” he said.

Tracy pointed out that a slight downside to this maniacal emphasis on physical conditioning is a commensurate loss of flexibility, one of the areas for which American gymnasts have been criticized. It’s a trade-off: In order to do the more complex acrobatic skills, the Americans have buffed up, but that has compromised the dancerlike flexibility prized by most gymnasts.

It also has changed the look of the modern gymnast. She is hardly the slender naïf of the ’70s. Sands is pleased with this shift. “There were the overly skinny kids for a while,” he noted. “There was a brief spurt of strong muscular girls—Mary Lou Retton was an example. And then it went back [to skinny]. And now it’s kind of gone back [to muscular]. I hope it never goes back. Strong explosive athletes are, indeed, healthier, better able to withstand the rigors.”

But even as the American gymnasts get stronger and amass difficulty levels that surpass those of their nearest international rivals, they are not recklessly and wantonly throwing skills. Elements are added carefully, incrementally even. Skills that are not properly mastered are taken out of routines. At the 2012 Olympic trials, Kyla Ross had been struggling mightily on her Amanar, crashing it repeatedly. Karolyi advised gymnast and coach to pull it from her program and replace it with the simpler double twisting vault, which she has performed successfully ever since.

This was in keeping with the Karolyis’ careerlong philosophy about gymnastics. Above all else, they prized not virtuosity but consistency in their gymnasts. They did the gymnastics they knew they could hit, day in and day out. No flashy stuff.

Consistency isn’t just a trait Martha Karolyi values in her gymnasts; it’s one she prizes in herself. When asked about her reputation for being strict in a 2006 interview with International Gymnast, she answered, “I don’t know if I’d say I’m strict. I’d rather say that I’m very consistent in my expectations.”

Copyright 2016 by Dvora Meyers. From The End of The Perfect 10 by Dvora Meyers, published by Touchstone, a division of Simon and Schuster, Inc. Reprinted with permission.