At the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, Czechoslovakian legend Vera Caslavska won the uneven bars with a routine, quite difficult for its time, in which she came to a full standing stop on the low bar, and then struck a majestic pose.

Compare that with the breathtaking fluidity (and flight!) of 2012 bars gold medalist Aliya Mustafina.

That’s only one of infinite examples of just how much women’s gymnastics has changed in the past 50 years. It’s not merely a more difficult version of the same sport. It’s an entirely new species of sport. In fact, just about everything has changed—except one bizarre but unavoidable detail: the fussiness of gymnasts’ hairdos.

During Sunday night’s qualifying competition, two things were obvious about the Rio cohort: Their skills are more spectacular than ever, and their hair looks like it was styled in 1968. In fact, this year’s de facto ’do—a half-messy looped topknot, omnipresent on everyone from the Russians to the Italians to our own gold-medal favorites, placed high on the crown in what I like to call the Britney-circa-2007 position, wobbling disconcertingly with the athlete’s every leap—is itself a callback to Caslavska’s own majestic bouffant, on display in all its glory during her iconic protest against the Soviet occupation on the silver-medal stand.

The unfortunate, and often racially tinged, dialogue surrounding the ponytail of 2012 all-around champion Gabby Douglas (who, by the way, responded with perfection) should make anyone wary of critiquing gymnasts’ hairstyles. Many would say it violates both feminist credo and common decency to assess athletes’ outward appearances when their performances are so clearly the star of the show. But I’m less interested in analyzing the hairstyles of individual athletes than in interrogating the culture that mandates such goofily baroque self-presentation.

Alex Livesey/Getty Images

Half a century ago, such ornate styles were perfectly understandable. The skills weren’t as extreme, and the women who completed them were athletes, sure, but ladies first and foremost, ready to waltz off the mat and prepare a roast. The early-season Mad Men hair never let you forget that, not for a second. This wasn’t a sport-sport, it was a performance, one undertaken within the constraints of what constituted acceptable acrobatic exertion. Anything that mussed up a beehive would have been considered scandalously dangerous for a lady to attempt.

So the original hair trends in gymnastics made sense. Now, they do not. Today’s elite gymnasts are absolute dynamos, world-class athletes whose conditioning rivals or surpasses that of any other major competitive sport. You would think that this would accompany a style metamorphosis that reflected the sport’s incredible feats of athleticism but still allowed for individual expression—that gymnasts would start looking more like Serena and less like Selena. And yet, gymnastics hair has remained curiously pageantlike, as evident in this spectacular, definitive history of gymnastics’ follicular trends from the blog the Gymternet. My own personal favorites (by which I mean I wore them on top of my own gymnast head): the foofy wedge and the aggressively shellacked mall bangs of the late ’80s and early ’90s.

What is going on here? Is there some sort of “insufficient glam” deduction? While the dizzying Code of Points has clear rules about attire—leotards must be “of elegant design” (and not transparent! and not high-cut!)—the document is noticeably mum on the tresses. The governing rules for USA Gymnastics, meanwhile, stipulate only that athletes be “well groomed” with “hair secured away from the face so as not to obscure her vision of the apparatus.”

Despite this lack of an official tonsorial code, the world’s best gymnasts appear to be abiding by unwritten rules that require them to look they’re ready for a sorority mixer.

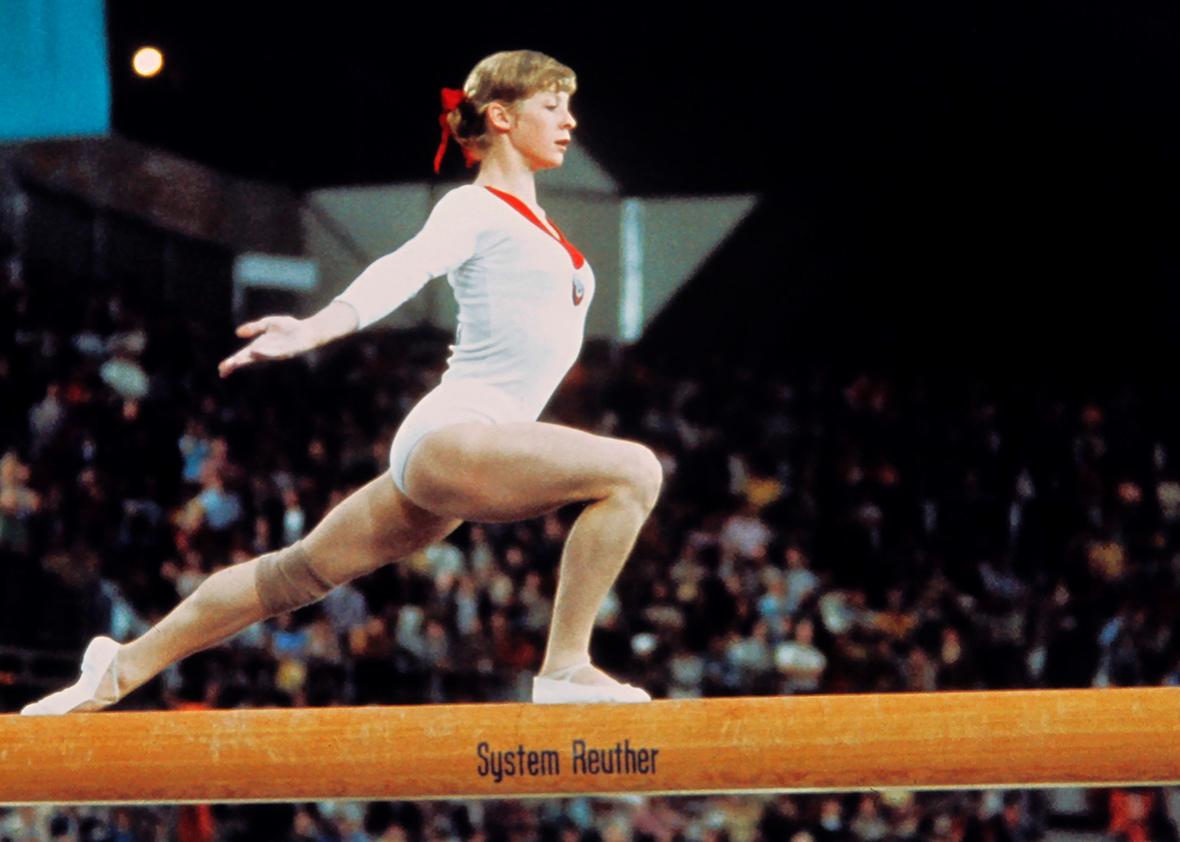

It didn’t have to be this way. Forty-four years ago, pint-size Olga Korbut took the 1972 Munich Games by storm with the revolutionary difficulty of her routines. Her mussed, yarn-tied pigtails are as etched in the memory of gymnastics fans as her groundbreaking back flips on the beam and bars. Olga had better things to do than futz with her hair.

AFP/Getty Images

The Korbut pigtails augured a brief shift in gymnastics hair reflective of the rightful focus on the athlete’s abilities rather than their ornamentation—a shift that was also apparent in the simple ponytail Nadia Comaneci wore as she broke the scoreboard in Montreal in 1976, the bowl cuts of the U.S.-boycotted 1980 Games, and on through to 1984, when Mary Lou Retton catapulted herself onto a Soviet-free medal stand in a low-maintenance pixie.

Kazuhiro Nogi/Getty Images

And then, in 1988, came the mall bangs apocalypse, and it all went to hell. In 1992 and 1996, as the Gymternet also points out, the tiny gymnasts were nearly eaten alive by their Scrunchies, and in 2000 and 2004, I was briefly afraid that the friction on the uneven bars might set the athletes alight, given the amount of shellac on their domes. The 2008 games brought a spectacular gold-silver sweep by Americans Nastia Liukin and Shawn Johnson—and also a teamwide uniformity in pompadour bangs. And, perhaps most ignominiously, 2012’s Fierce Five vaulted into our hearts sporting absolutely stunning gymnastics—and perhaps the most perplexing appropriation of prevailing hair-fashion, aka what I like to call the hungover Tri-Delt, a deceptively complex half-untucked bun. And that brings us back to now, and the sproingy cheerleader braid-bobbles of the Rio Games.

Franck Fife/Getty Images

Shooter Ginny Thrasher, who is 19 and won Rio’s first gold for the U.S. in the women’s air rifle, presumably doesn’t have much time for frat parties at West Virginia. Track icon Allyson Felix was just 18 at her first Olympics in Beijing, and managed to run without looking like a Dolly Parton backup singer. But then, the grooming conventions of their sports don’t require pageant hair. Why gymnastics, still?

As difficult as women’s gymnastics is athletically, the tricky business of performance and of showmanship remains. That’s where those godforsaken Swarovski monstrosities that claim to be performance garments come in, as well as the face-breaking smiles each athlete is expect to display after (and, on floor, during) each performance.

The hair is the way it is because gymnastics culture still prioritizes aspects of physical appearance that should be irrelevant (and that are in sports such as track and field). These are facts that should ring disturbingly familiar to women everywhere: The “girls” must perform their jobs to perfection, and do it while conforming to the current gender-normative metrics of acceptable female attractiveness.

I want gymnasts (and everyone else) to wear their hair any way they please, and if that means a bobble-bun, so be it. (Even though, for what it’s worth, this year’s weird buns really disrupt the “line,” as they say, of the athlete.) But gymnastics is notorious for being a sport where the athletes have little or no autonomy, at best living every second of their day according to the punishing training schedules of a semicentralized quasi–Eastern Bloc training system, and at worst suffering silently as their coaches commit unthinkable abuses largely unchecked. It’s hard not to look at these hairdos and wonder whether they are really expressions of youthful, individual personality—or whether they’re relics of an oppressive style guide that’s more grounded in 1968 than 2016.