Earlier this year, ESPN’s “30 for 30” documentary series tackled the Nancy Kerrigan–Tonya Harding story with The Price of Gold, directed by Nanette Burstein and available to stream on Netflix. Kerrigan herself did not participate, but not because the former figure skater is unwilling to talk about what Harding did or did not know was going to happen to Kerrigan’s knee in the lead-up to the 1994 Olympics in Lillehammer, Norway. Instead, she had an exclusive deal to speak with NBC. (Kerrigan’s husband appears in The Price of Gold.) NBC’s own documentary about the subject, Nancy & Tonya, aired Sunday night, on the closing night of the Olympics and the 20th anniversary of Lillehammer, with Kerrigan and Harding’s full participation. After it was over, Kerrigan spoke in the studio with Bob Costas and joked that she has done the movie because she hopes “we’re not going to be back here 40 years from now.” Fat chance.

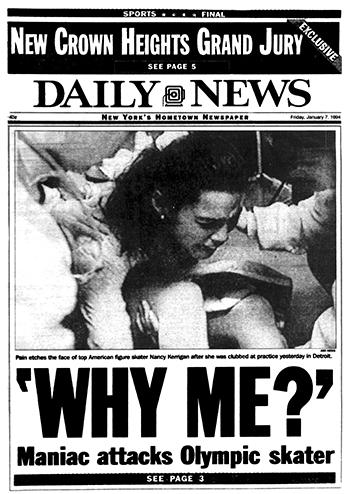

The Kerrigan-Harding saga was a gigantic, salacious news story nearly from the moment it began—a tale that boosted figure skating’s fortunes, seared itself into the public consciousness, and hovers over the women involved to this day. From the start, it was seen as a battle of archetypes, a story that was—as one of the subjects in The Price of Gold says—so “rich in its black and whites, no one looked for gray.” Harding was the trailer trash, even before the knee-capping: She grew up poor in Oregon in an unstable family (though never, as she tells NBC, in a trailer park). She had immense athleticism—she’s the first American woman ever to land a triple axel in competition—but also teased blond hair and flashy costumes. Kerrigan was the ice princess, who cannily melded her long lines and instinctual hauteur with elegant Vera Wang costumes.

Both documentaries set out to complicate these stereotypes. A superficial gloss of the differences between The Price of Gold and Nancy & Tonya is that the former complicates the Harding stereotype, the latter the Kerrigan one. But the real takeaway is that these stereotypes, 20 years later, remain as powerful as ever. The two movies contain a lot of overlapping footage and interviews and historical moments, but taken together, they show just how intractable perspective can be: NBC is still presenting Harding as crass, and Harding is still devoted to the narrative of Kerrigan as the ultimate snob.

The Price of Gold is Tonya Harding’s story. Burstein sees Harding as a tragic hero, or tragic villain—a woman undone by her own flaws. In the movie Harding cuts a sympathetic, though not innocent, figure. Much more than the NBC documentary, it details Harding’s unstable upbringing, her mother’s abuse, her poverty, and how skating was “her way out of the gutter,” in the words of her coach at the time. It also details the intense snobbery of the figure skating world, which frowned on Harding’s costumes, music choices, and powerful skating style. But ultimately, in both films, Harding emerges as her own worst enemy, not just because she hung around with bunch of criminal galoots, but because she failed to live up to her own potential. She was unfocused and unprepared even before she found herself caught up in a Coen brothers caper gone radically wrong.

To this day, Harding barely accepts responsibility for anything that happened, even to herself. Kerrigan was showered with sponsorships after winning the bronze in 1992, while Harding, who came in fourth, was ignored: Skating is not fair. But Harding sees only a conspiracy against her and not her own part in her poor Olympic performances. In Nancy & Tonya she says of her terrible showing in Lillehammer, “It wouldn’t matter if I did three triple axels; the association wasn’t going to let me represent them.” Needless to say, she did not even do one triple axel, but instead sobbed about a broken shoelace to the judges, who gave her a whole new free skate. She sees people taking things from her that she never earned.

But if Tonya bristles at the way the skating world dismissed and marginalized her, she continues to see Nancy as symbol, not a person. One of the ironies of Kerrigan and Harding’s story is that they are more similar to each other than they seem. Kerrigan was also a working-class tomboy who loved to jump, but in the words of NBC, “Kerrigan and her team learned to play by the unwritten rules of the game,” bringing “class, polish, and refinement” to her performances, something Harding couldn’t quite do.

Harding, in Nancy & Tonya, absolutely bristles to hear her childhood compared to Kerrigan’s, insisting that parental stability made them entirely different. (Kerrigan, generously, agrees with this assessment.) Harding sees herself as mistreated, especially as compared to Kerrigan, for whom she exhibits almost no sympathy: “She was a great skater. I was a great skater. But of course she was treated like a huge queen.” In the climatic moment of The Price of Gold, she says, “She’s a princess and I’m a pile of crap, but it’s OK. … You know, no, it’s not OK, how I was treated by everybody out there is not OK.”

NBC is not kind to Harding. She is introduced at a karaoke bar, warbling. She gets angry and snappish at the interviewer, Mary Carillo. NBC fixates on the fact that she smoked and drank beer while training. It shows her making excuses about the 1992 Games in Albertville, France. But the most damning thing to happen in Nancy & Tonya is the presence of Kerrigan herself, whose absence in The Price of Gold doesn’t make the film any less fascinating but does permit the audience to continue to think of Kerrigan as aloof and removed. NBC goes out of its way to address Kerrigan’s iciness, to explain that she was shy, under stress, scared, and, actually really loves Disney World. But Kerrigan has also gotten more comfortable on camera with age, and she smiles often, something she barely ever did in interviews from the ’90s. She’s fairly open and a little funny (“I am so lucky they just didn’t have it together as good criminals”) and surprisingly generous; she describes Harding as “jumping huge.” Meanwhile, Harding can’t give even gold medal winner Oksana Baiul a clean compliment: “Her jumps were done with ease, like mine were done with ease, but they weren’t as big.”

Kerrigan may have been the one who was attacked, but the incident has scarred Harding’s life much more so than Kerrigan’s. At the time, Kerrigan was faced with a massive challenge that she overcame. She skated wonderfully at the Olympics, even if she only won silver—a show of character she gets to relish every day. After the Olympics, she went on to make millions, profiting from the booming interest in figure skating that she and Harding had wrought. She can afford to be generous to Harding. Meanwhile, the incident tarnished Harding’s life. She was banned from skating, which was her livelihood; stripped of her national title; and turned into a joke. She participated, at least to some extent, in a scheme to take down Kerrigan that only robbed Harding of her calling and her dreams. That’s a pretty bitter pill to swallow, and Harding, as these two documentaries make clear, is still chewing it over.