The Olympians of 100 years ago did not remotely resemble the finely chiseled athletes of today. Many competitors were scrawny, plump, or simply ordinary looking. In a recent piece in the Guardian, Frank Keating explained that the 1912 Stockholm Games were “the last Olympics where any individual could just turn up and hope to enter a competition.” In that era, the idea that “natural” skill might enable someone to win a competition without any specialized training was still widely embraced.

Official Olympic Report, December 1913 via the LA84 Foundation Digital Archive.

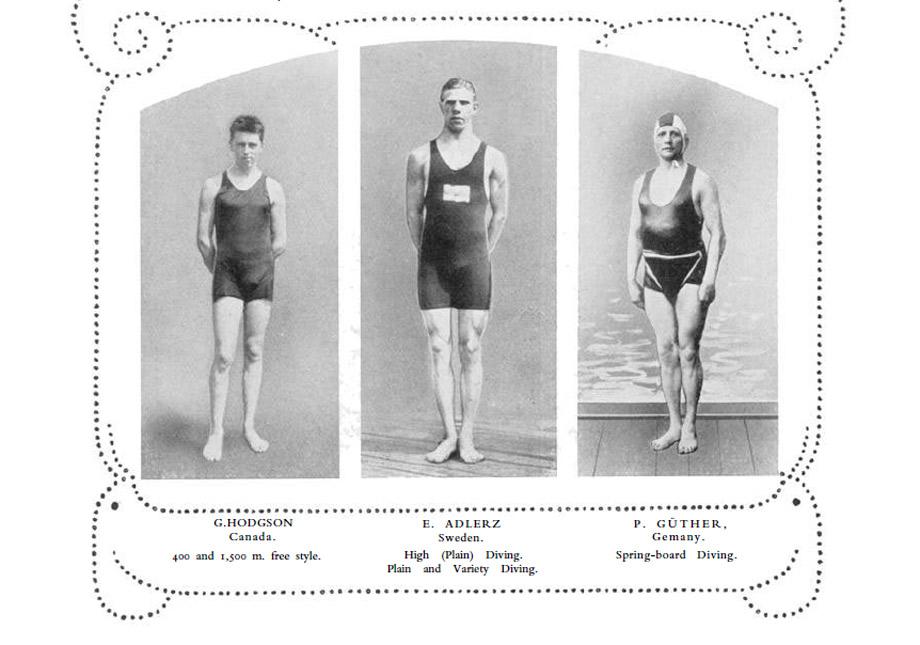

While competitors’ bodies might not seem impressive by 2012 standards, athletes did accomplish some amazing feats. Canada’s George Ritchie Hodgson, above left, never lost a race in the three years he competed as a swimmer. In Stockholm, he set a world record in the 1,500-meter freestyle “without effort,” according to the official 1912 Olympic Report. At 22 minutes, his record time was nearly eight minutes longer than that of current world record holder Sun Yang. But still, it was only 1912.

Flickr Commons project, 2008, via Library of Congress.

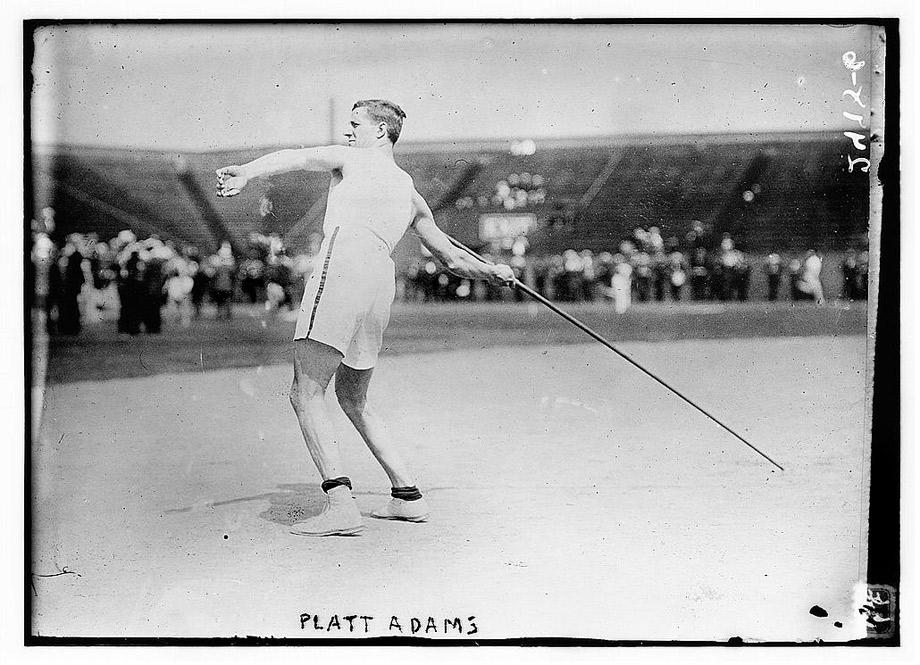

In 1912, specialized athletic clothing had not yet swept the world. Above, U.S. track and field athlete Platt Adams throws the javelin in high-waisted shorts and shoes resembling Converse.

Official Olympic Report, December 1913 via the LA84 Foundation Digital Archive.

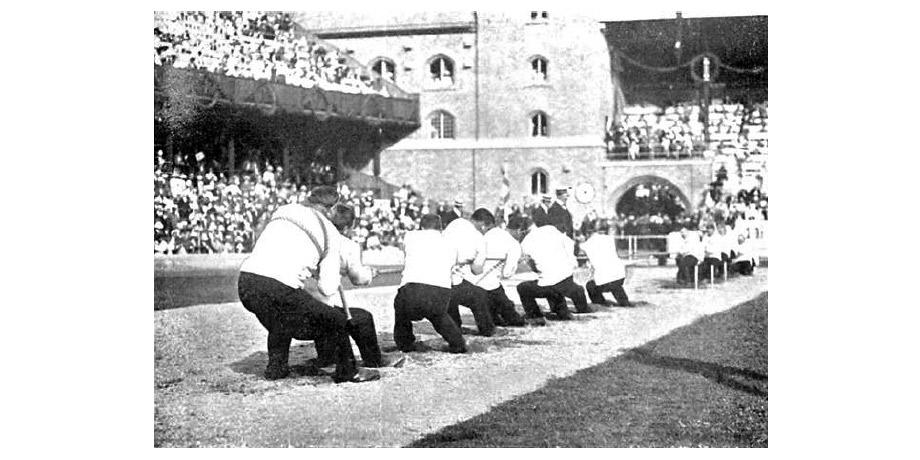

In 1912, tug-of-war was an Olympic event and the games’ hosts were considered some of its best practitioners. Pictured above is a tug-of-war bout between Sweden, on the right, and Great Britain. The sport is “especially suited to the natural bent of the Swede,” the official 1912 Olympic Report declared.

Official Olympic Report, December 1913 via the LA84 Foundation Digital Archive.

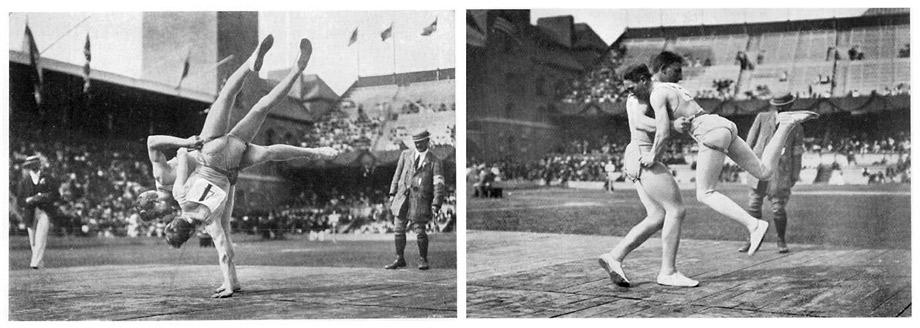

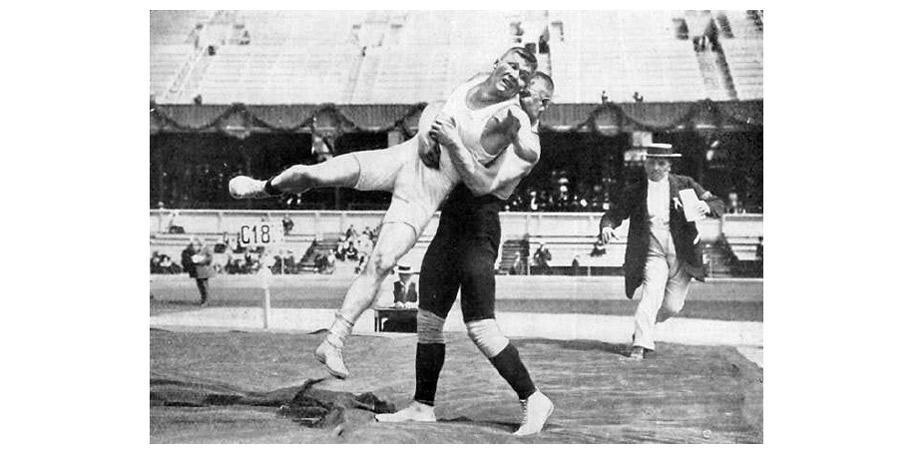

Olympic wrestling had a graceful, dance-like feel in 1912. Above, two wrestlers engage in traditional Icelandic “Glima” wrestling, grasping each other by the handles of their leather girdles and swinging each other through the air.

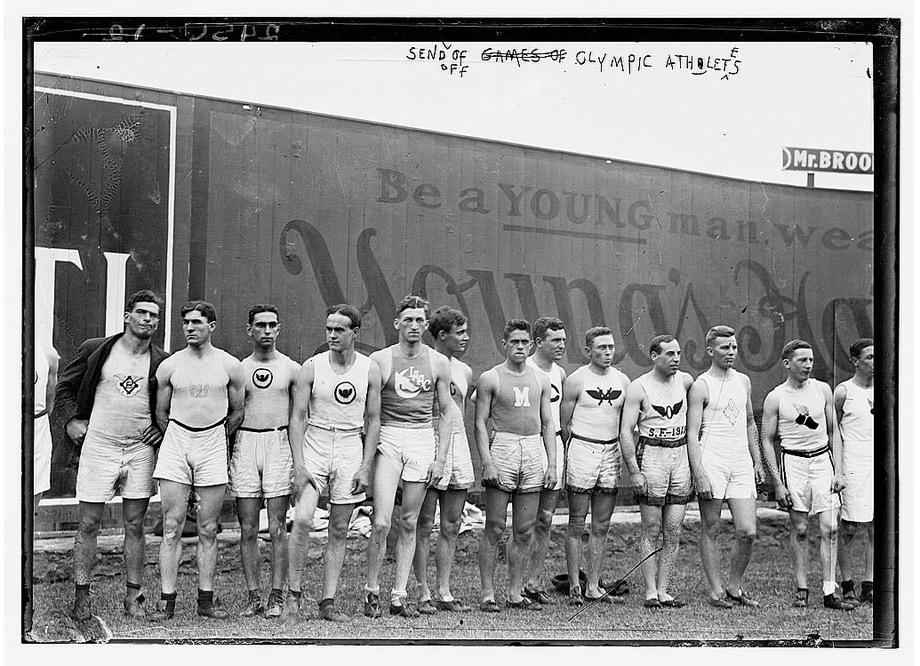

Long before aerodynamic track suits made of recycled water bottles a pair of short trousers and a simple jersey were considered sufficient. Pictured above, American bronze medal winning hammer thrower C.C. Childs, left, and Canadian-born American hammer thrower Simon Peter Gillis pose at Hilltop Park in New York City before departing for the games in Stockholm.

Flickr Commons project and database, 2008, via Library of Congress.

These days, athletes wear running shoes made of fibers thinner than strands of human hair. But in 1912, these were the shoes American athletes showed off at their big sendoff. Sock color and height varied.

Flickr Commons project and database, 2008, via Library of Congress.

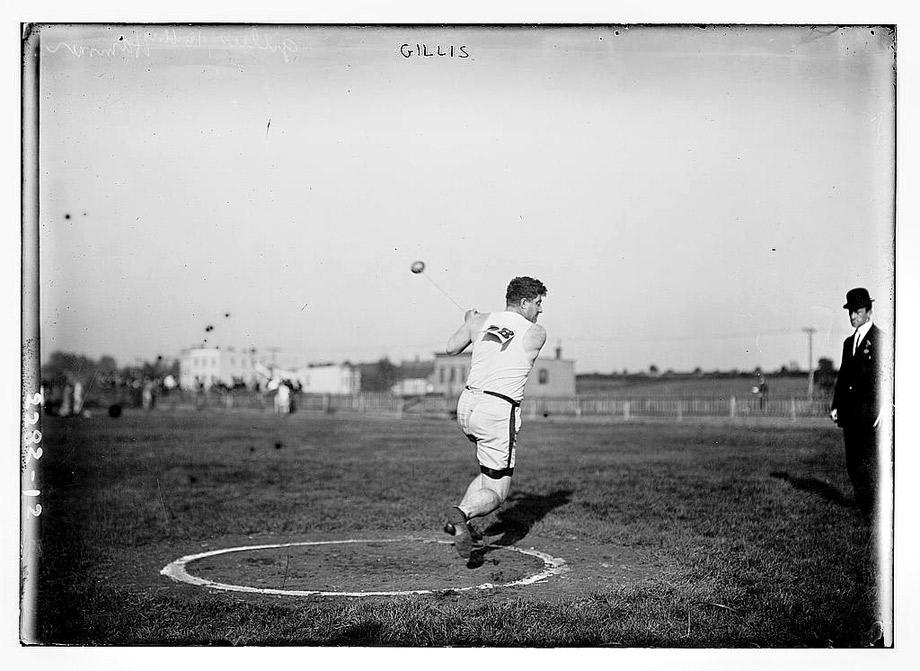

They just don’t make judge hats like they used to. (Note the dapper judge at far right, observing Canada’s Duncan Gillis in the hammer throw.)

Official Olympic Report, December 1913 via the LA84 Foundation Digital Archive.

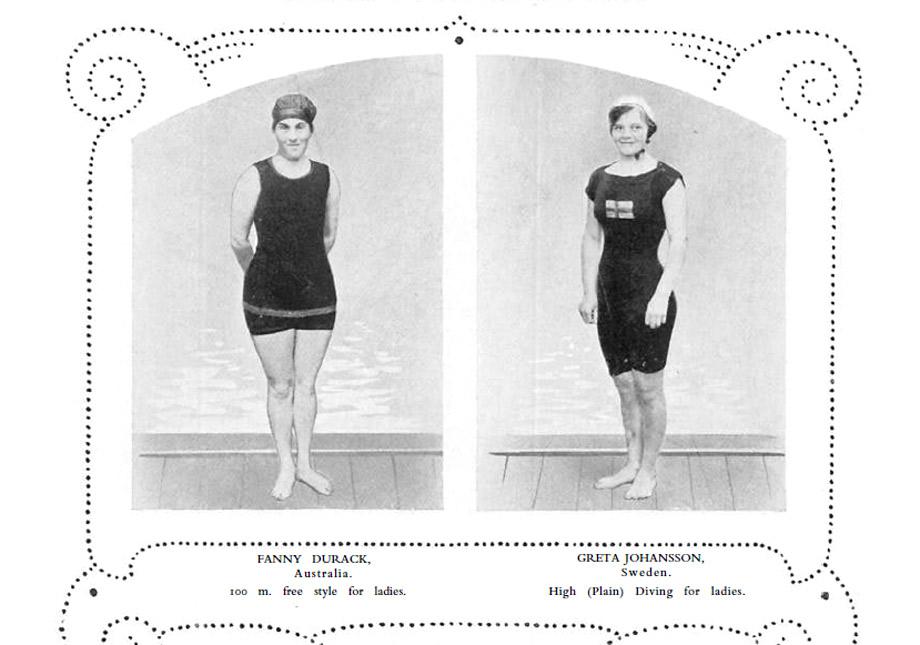

Swimsuits provided ample coverage in 1912. At left is a competitor in the 100-meter freestyle. At right is a diver.

Official Olympic Report, December 1913 via the LA84 Foundation Digital Archive.

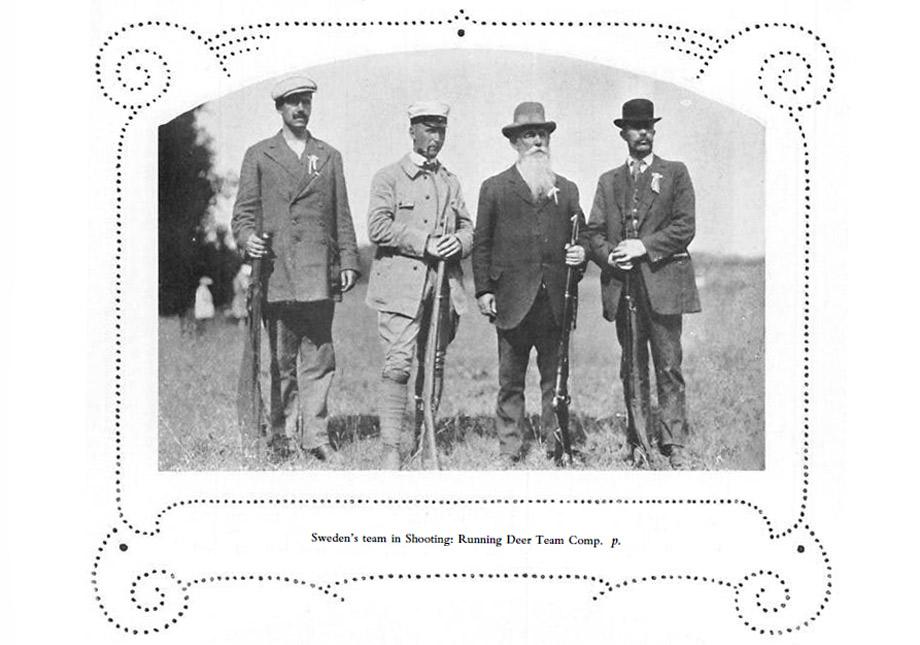

There was room for athletes of all ages in the Olympics of 1912. Pictured above is the winning team from Sweden in the “running deer” category, which required competitors to shoot at a moving deer-shaped target. The team featured a father and son. Alfred Swahn, far left, won the gold individually. His father, 64, came in fifth but continued to make history, going on to participate in the Antwerp Games of 1920 at age 72, making him the oldest Olympian in history.

Though these clothes may not seem very sporty, they are also multipurpose. After a mixed doubles match, participants could stroll off to recite poetry at the nearest gazebo without looking out of place.

Official Olympic Report, December 1913 via the LA84 Foundation Digital Archive.

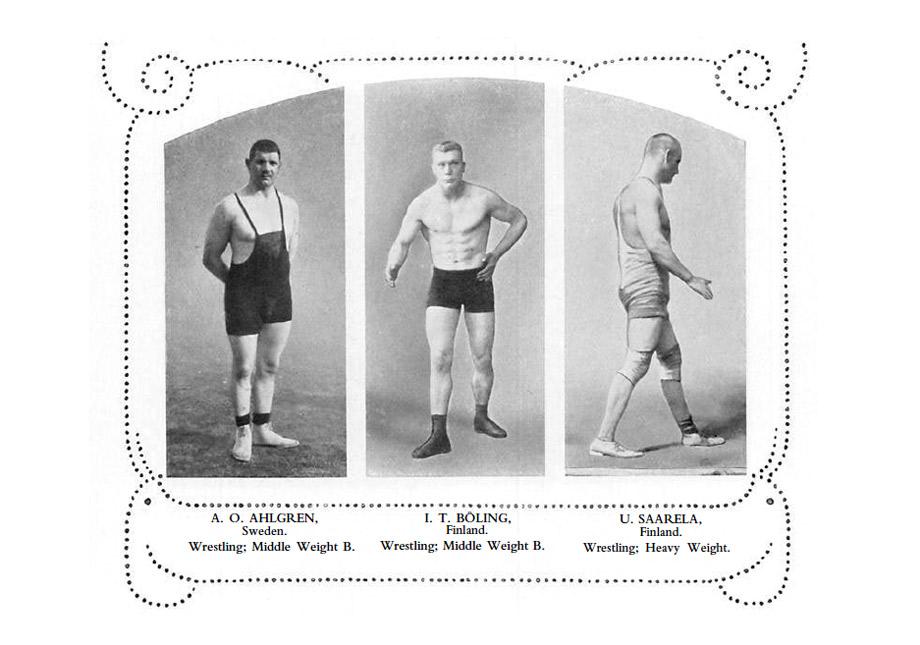

Watching a wrestling match could be an extensive commitment in 1912. Anders Ahlgren, left, of Sweden, and Ivar Böhling, of Finland, wrestled for nine hours until their match was declared a tie. Both had to settle for silver medals.

Official Olympic Report, December 1913 via the LA84 Foundation Digital Archive.

The endurance prize of 1912 goes to Estonian wrestler Martin Klein, representing Russia, and Alfred Asikainen of Finland, who wrestled for 11 hours and 40 minutes in the semifinals before Klein came out on top. (Their motives may have been political.) Unfortunately, the effort may have tired him out—Klein lost the gold-medal match.

Official Olympic Report, December 1913 via the LA84 Foundation Digital Archive.

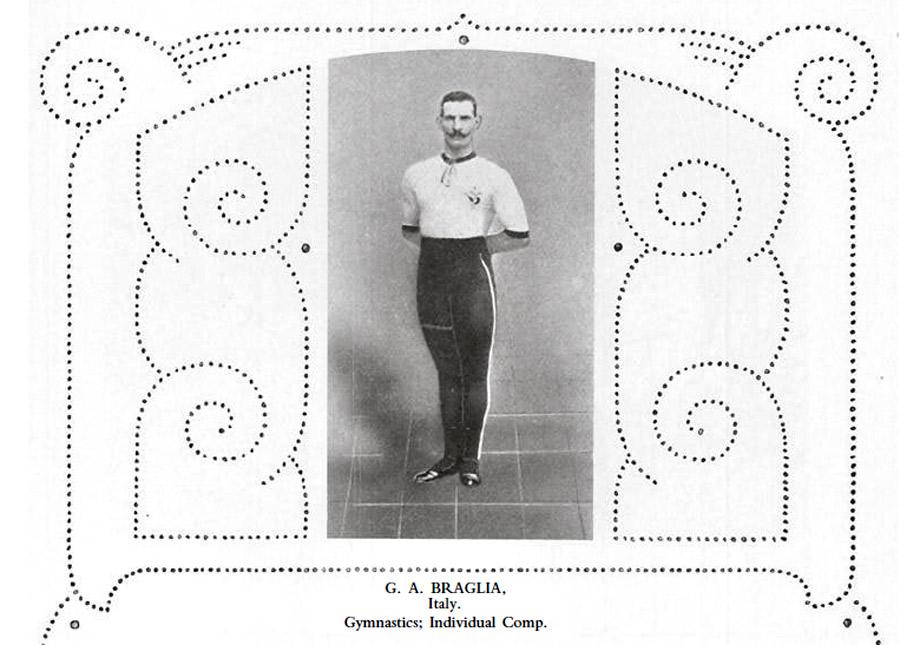

Many competitors donned mustaches in 1912. Few could compete with Italian Alberto Braglia, who won the gold for individual gymnastics that year, surely aided by his handsome facial hair.

Flickr Commons project and database, 2008, via Library of Congress.

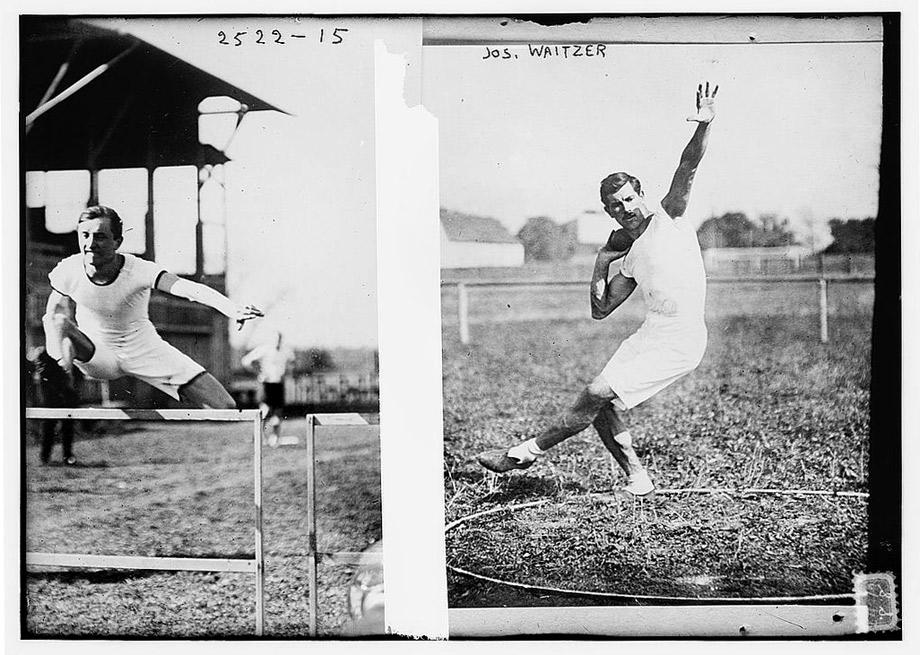

Germany’s Josef Waitzer, right, also donned a dashing ’stache while competing in the javelin, the discus, and the pentathlon.

Official Olympic Report, December 1913 via the LA84 Foundation Digital Archive.

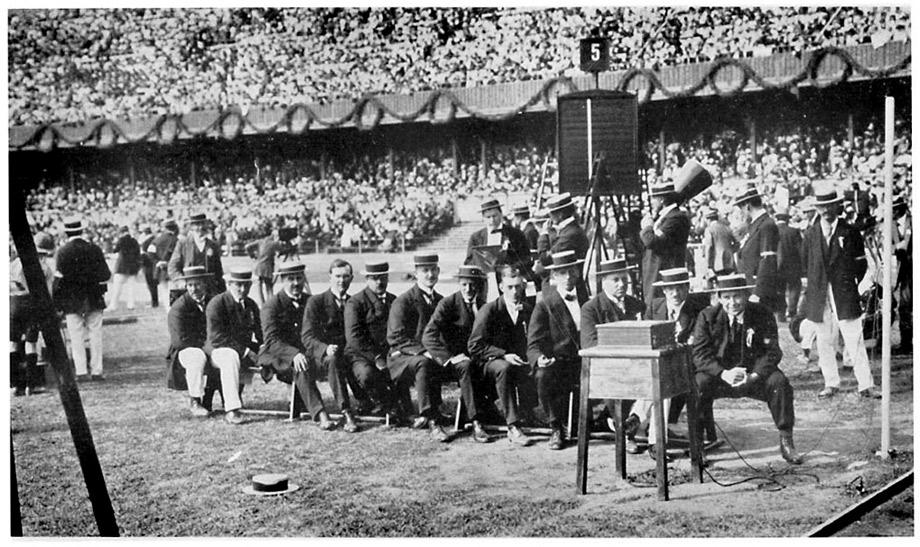

This is what timekeepers looked like in 1912. Back then, they were considered technological renegades. An automatic timing apparatus was invented for the Stockholm Olympics, connecting the revolver used to start races on the track with “first-class chronometers” and the judge’s stop-watch. Additionally, a “photographic apparatus” that would snap the winner and the runners-up was employed for the first time.

Read the rest of Slate’s coverage of the London Olympics.