Greek patriots may look askance at London hosting its third Olympic Games while the event’s ancient originator has hosted it only twice. On one level, the resentment is understandable. The classical games were the greatest emblem of Hellenic culture for nearly 11 centuries, from 776 B.C. to 393 A.D. But the modern revival of the Olympics in 1896, after a 1,500-year hiatus, is not a black-and-white tale of a Greek ritual being pilfered. In fact, the 19th-century restoration might never have occurred without the efforts of the British, particularly a group of eccentric, upper-crust Victorians who were obsessed with sports, the classics, and the idealized male form in Greek art.

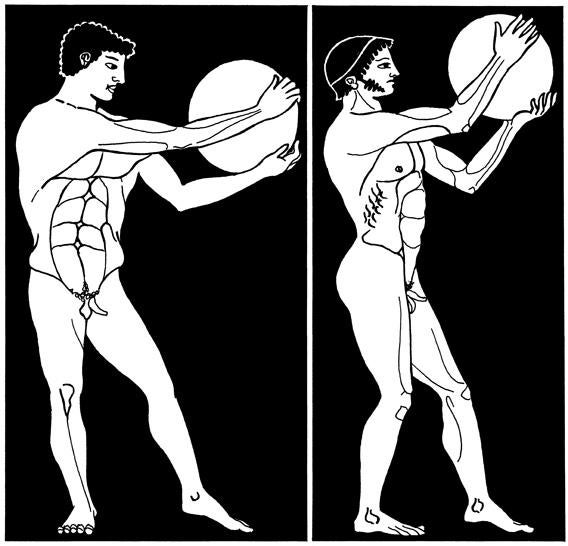

Even in ancient Britain, an outpost of the Roman Empire from 43-410, Greek-style athletics were not unknown. Provincial towns such as Bath had their thermae, heated bathing complexes with splendid indoor pools and an attached palaestra for exercising in the revered Greek style. Although gladiatorial combats were more popular with the British crowds, fragments of pottery, glass, and mosaics have been discovered depicting Greek athletic events such as discus throwing, wrestling, and boxing. Chariot racing, a key event at the Olympics, was also followed with enthusiasm: In 2004, archaeologists unearthed a stadium in Colchester that dates back around 2,000 years.

The ancient Olympic Games ended in the fourth century, when its pagan rituals were no longer tolerated by Christian emperors and the Roman Empire itself was crumbling under the weight of barbarian invasions. The magnificent shrine where the games were held, Olympia, was repeatedly sacked, its treasures destroyed, and its location forgotten by all but local peasants. It would not be for another 1,000 years, during the Renaissance, that Britons would join the European revival of interest in the classical world. Ancient sagas became grist for Shakespeare, while Pindar’s Olympic odes endowed the name of Olympia with a magical talismanic ring.

Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

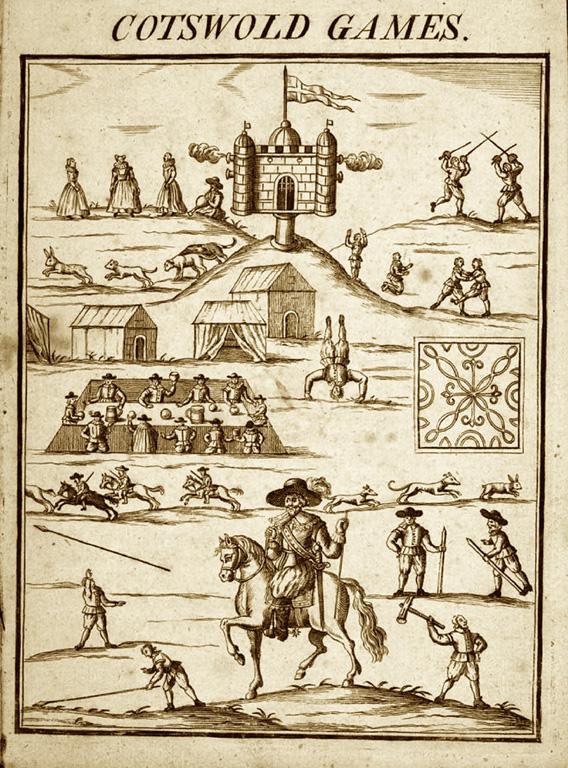

It was during this period that an extravagant, history-loving lawyer named Robert Dover convened the “Olympick” festival in the green hillsides of the Cotswolds. At the time, in the 1620s, Puritans were attacking England’s traditional rural festivals for promoting gambling, drinking, and lewd behavior. Dover’s Olympicks were an act of defiance against this dour movement, and as an annual event, it lured thousands of spectators of all social classes to sit on muddy hillsides near the village of Chipping Campden. A motley range of sports was on the schedule, including hammer throwing, bear baiting, shin kicking, and the brutally violent “fighting with cudgels,” which left the contestants bloody and toothless (an accidental echo of the goriest of the ancient Greek body contact sports, the pankration).

The entire festival was marked by heavy imbibing of ale and a genial air of license, though Dover also included a “Homeric harpist” in an attempt to lift the tone and thus attract the gentry. One English poet in 1636 hailed Dover as a “Hero of this our Age.” But the exuberant festival could not last. The Cotswold games were canceled in 1642 due to nearby fighting during the civil war. Dover died heartbroken eight years later.

Our modern conception of sport would be born two centuries later in Victorian Britain. During this period, the growing middle class repressed lawless, brutal, rural competitions in favor of more civilized and regulated affairs. Teachers at exclusive schools such as Eton and Rugby began to espouse that physical education was crucial for health, moral well-being, team spirit, and general “manliness of character.” Rules for organized team sports such as soccer were codified. Europeans and Americans looked on at first in bemusement, then in admiration, as the cult of sports took hold in Victorian society and seemed to go hand-in-hand with the invincibility of the British Empire.

Copyright Lesley Thelander.

This new passion for exercise dovetailed naturally with curiosity about ancient Greece, which grew throughout the 19th century. Interest had been rekindled in 1766, when a group of traveling English scholars from the Society of Dilettanti “rediscovered” the site of ancient Olympia. By the 1800s, imaginative Oxford and Cambridge dons were idealizing the ancient athletic tradition and studying Greek statues and vases to revive events like the javelin and discus throws, which had not been practiced for more than a millennium.

The admiration for the Greek ideal of the male physique was not purely aesthetic. For upper-crust Victorians, conversations about “Greek love” of a man for a young boy allowed the expression of homoerotic desires that were otherwise forbidden. As historian Linda Dowling has put it, “the prestige of Greece … was so massive that invocations of Hellenism could cast a veil of respectability over even a hitherto unmentionable vice or crime.”

The Victorian enthusiasm for sports was accompanied by class-specific distortions. On the scantiest of evidence, scholars espoused the idea that ancient Greek athletes were all “amateurs” who competed without reward except for wreaths. This cult of amateurism, which was later officially codified by organizations like the Amateur Athletic Association of England, has been denounced by historian David C. Young as “a kind of historical hoax” twisting ancient Greek texts to maintain an elitist sporting culture. In fact, except at the Olympics and three other “crown” games, the ancients lavished material prizes on the victors, who gained instant celebrity status. Even with regard to the Olympics, the material rewards for athletes were enormous once they returned to their home cities.

These amateurs-only regulations conveniently supported the new movement to keep the working classes out of top competitions, so educated gentlemen could prove they were superior to the masses in physical achievements as well as (they believed) mind and character. Under the new rules, any athlete who had ever accepted financial reward for training or competing was disqualified from the most prestigious contests, ensuring that sports would be reserved for gilded youth who had the funds and leisure time to train.

A more democratic development occurred in 1850, when an English country doctor began another version of a revived “Olympian Games.” The doctor, a devoted classicist named William Penny Brookes, launched these new Olympics in a Shropshire village called Much Wenlock. Surrounded by emerald green hills and attended by country gents, local merchants, and ruddy-faced farmers, the event had the air of a quaint rural carnival, although one more sober than Dover’s Olympicks.

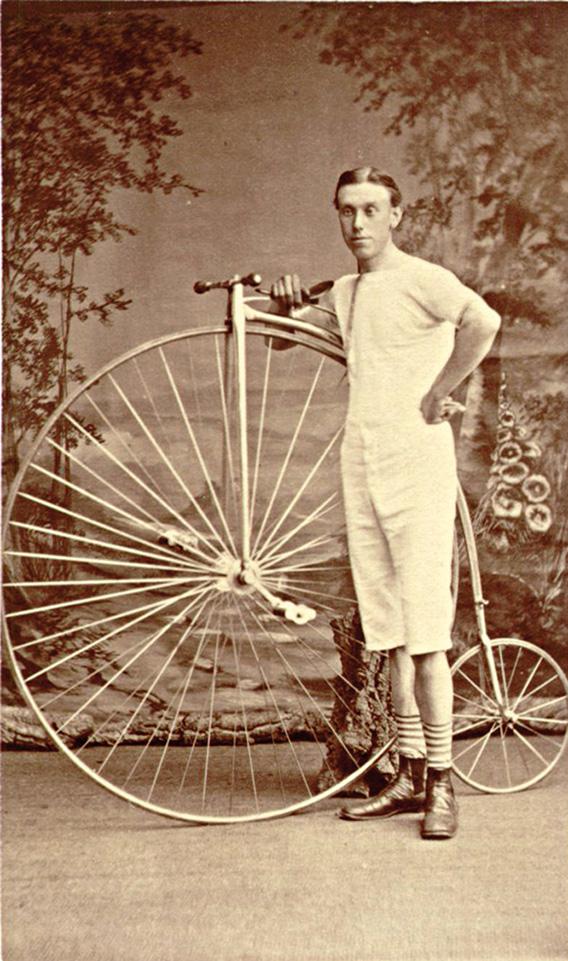

It’s difficult to picture the event without invoking Monty Python’s Flying Circus, for Brookes had a fondness for flamboyant costumes and theatrical rituals. The Olympian herald wore a cloak and hat with a plume and announced each competition with a bugle. A key event was the medieval-style “tilting at the ring,” where horseback riders would try to pierce a ring with a lance. Other competitions were a peculiar mix of the highbrow (foot races, cycling, archery, hurdles, the pentathlon) and the indulgent (“races for old women.”) Prizes ranged from silver trophies to a pound of fresh tea. In 1860, the games at Much Wenlock began a tradition of crowning its victors with a wreath, in homage to ancient tradition. The presenter was usually the local vicar’s daughter, outfitted less like an ancient Greek sylph than one of Queen Victoria’s dowdy nieces in a heavy bustle dress.

Photo courtesy Wenlock Olympian Society.

Brookes’ revived Olympian Games are still held in Shropshire every July. Many relics from the Victorian era, including the herald’s uniforms, are still on view at the Much Wenlock Museum. It is these games that are the seed of our modern Olympics. Not only did imitations of the event spring up around Britain, but Brookes also espoused the notion that the Greeks themselves should revive an international version of the Olympics on their own soil. When he learned of a local Olympics being held in Athens in 1859 funded by a Greek businessman named Evangelos Zappas, he sent a Wenlock Cup to be awarded to the winner of a long foot race, along with encouragement that the festival should be turned into a much grander event. Brookes repeatedly pressed the idea of an international Olympics upon the Greek minister in London, without success—the Greeks felt that the enterprise would be too expensive for their struggling nation.

Yet the fascination with the Greek world continued to grow, as celebrity archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann discovered the sites of Troy and Mycenae. From 1875, German archaeologists also began excavating the site of Olympia. When they revealed the sanctuary complex and unearthed 14,000 objects, including such masterpieces as the Hermes of Praxiteles, the pages of Homer and Pindar sprang to life. The world’s enthusiasm for the heroes of Greek antiquity was reaching fever pitch.

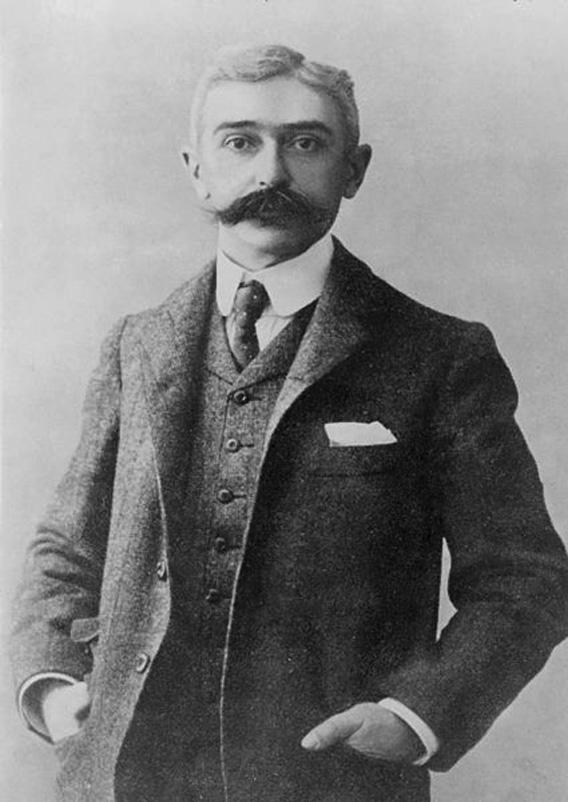

Into this heady milieu stepped the young French aristocrat Baron Pierre de Coubertin, a diminutive, obsessive, and wildly energetic figure who would eventually have himself proclaimed the “father of the modern Olympics.”

Coubertin, who was raised in the shadow of France’s humiliating 1871 defeat in the Franco-Prussian war, became a committed Anglophile (a stance that was then very unfashionable in Paris). He was enchanted as a teenager by the novel Tom Brown’s Schooldays, a paean to the sporting traditions of Rugby School. Coubertin become convinced that the rigorous British athletic culture was the basis for the empire’s success—a marked contrast to France’s evident physical “degeneracy”—and became a fitness advocate. In 1883, at the age of 20, lithe, muscular, and sporting an enormous handlebar moustache, Coubertin made a pilgrimage to the fields of Rugby to study the Britons’ methods. He followed this in 1889 with a journey to the United States, where he discovered new spectator sports such as baseball and met with Teddy Roosevelt, who had taken up outdoor adventure and strenuous exercise as a way to overcome his sickly adolescence. Soon, Coubertin was advertising in European newspapers for assistance in organizing a congress on physical training for the coming Paris Exhibition. He was promptly contacted by that tireless British Olympic advocate, William Penny Brookes—a man who, at the very least, deserves the title of “grandfather of the modern Olympics.”

Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

In 1890, Coubertin accepted Brookes’ invitation to attend the Olympian Games at Much Wenlock. We do not know exactly what transpired between the mutton-chopped 81-year-old country squire and the excitable 27-year-old Frenchman as they wandered the country pubs, enjoyed tea and scones, and witnessed a special session of the athletic extravaganza of Shropshire. But it’s clear that Coubertin was bewitched by the whole event, particularly the florid pomp and ritual.

Historians have no doubt that Brookes espoused his idea that the Olympics should be revived on an international level—and that Coubertin, with his youthful energy, connections, wealth, and deft organizational skills, was the man to do it. On his return to France, Coubertin wrote that Brookes was a true pioneer: “If the Olympic Games that modern Greece has not yet been able to revive still survives today, it is due, not to a Greek, but to Dr. W. P. Brookes.” In another essay, he raved: “It is safe to say that the Wenlock people alone have preserved and followed the true Olympian traditions.”

Coubertin also swallowed some of the British academics’ class-based views of the ancient Games. His acceptance of the theory that the Greeks were “amateurs” would distort the rules of participation in the Games for decades. (In 1912, for example, U.S. athlete Jim Thorpe, a Native American from an impoverished background, was stripped of the medals he earned for his brilliant victories in Stockholm because he had once competed for a few dollars a week in semiprofessional baseball; the medals were only restored by the Olympic Committee in 1983, 30 years after his death.) Coubertin also accepted the romantic belief that the ancient “sacred truce,” which restricted warfare at the time of every Olympic Games, had been a genuine force for peace. (In fact, it was intended as a limited truce between the endlessly feuding Greek city-states to enable athletes and spectators to travel to Olympia in safety.) And Coubertin’s often-voiced Olympic credo—“The important thing in the Olympic Games is not winning but taking part. The essential thing in life is not conquering but fighting well”—would have been incomprehensible to the ancients, for whom victory was everything and anything less worthy of mockery.

Courtesy Amazon.com

Brookes died one year before he could see his dream of an international Olympics realized, in Athens in 1896. Over time, Coubertin, an inveterate self-mythologizer, played down Brookes’ role as a mentor, preferring to cast himself as a heroic rénovateur. He would make two telling pilgrimages to Olympia itself. The first was early, in 1894, just after he had confirmed that the first Athens games would occur two years later. After wandering the ruins, he recognized his own arrogance in reviving the Olympics after a 1,500-year hiatus. (“I became aware in this sacred place of the size of the task which I had undertaken,” he wrote, “and I glimpsed all the hazards which would dog me on the way.”) His second visit was in 1927, after the Olympics had become a fixture. He was invited by the Greek government for the official unveiling of a stele, or stone pillar, in his honor. Now he took a more sober, long-range view of his efforts and meditated more humbly on his achievement. Merit, he said, involves overcoming great obstacles. “Favored by lot in many respects … I count no such victories to my credit.”

Before his death in 1937, he arranged for his body to be buried with the remains of his wife in Lausanne, Switzerland, but his heart to be sent to Olympia, where it remains today inside his commemorative pillar. It was a classic Coubertin flourish, linking himself forever to the ancients who had disported there millennia before. The French baron certainly deserves his place of honor: No one but Coubertin had the passion or the political skill to carry the Olympic plan to fruition, and he spent his family fortune on the Olympic project, dying in virtual poverty. But it also must be remembered that he tapped the unlikely roots of rural Britain. Perhaps there should be another monument to two less continental figures who played essential supporting roles—Robert Dover and William Penny Brookes, with statues of them both raising a glass of sherry to the Greeks.

This piece is adapted from the introduction to Tony Perrottet’s The Naked Olympics: the True Story of the Ancient Games.