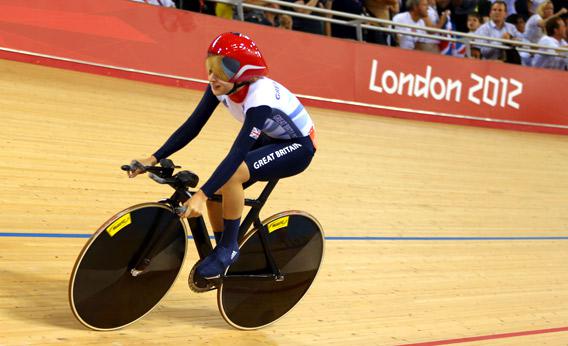

Great Britain sprinted its way to a fifth gold medal in track cycling last night, a success that led French team director Isabelle Gautheron to wonder aloud whether the team was using “magic wheels.” Track cyclists do use unusual wheels, often riding a spoke wheel in the front and the more unusual disc wheel in the back. Why do track cyclists use disc wheels while other kinds of cyclists don’t?

Because they’re more aerodynamic, though they have lots of disadvantages. Different cycling events call for different kinds of wheels. Disc wheels don’t encounter the air resistance that spokes do, but they’re also heavier, less maneuverable, and can be blown around—or even right out from under you—in a strong crosswind. An indoor track, where races tend to be short and flat and require less turning, is a great place for disc wheels. Spoke wheels, because they are lighter, more maneuverable, better at climbing, and aren’t so easily caught by crosswinds, are ideal for outdoor races that are curvy, hilly, or long. That’s why you don’t see disc wheels in the mountains of the Tour de France.

Some cyclists seek the best of both wheels by using a spoke wheel on the front, because it does the turning, and a disc wheel on the back—especially if there is only moderate wind or slow curves. Other cyclists may use styles of wheels that fall somewhere in between: carbon wheels that have only three or four spokes. These wheels offer some of the advantages of each type, being more aerodynamic than spoke wheels and lighter than disc wheels, with handling somewhere in between. Using disc wheels in front and back is fairly rare.

The International Cycling Union (or UCI, after its French name Union Cycliste Internationale), which governs worldwide cycling events including the Olympics (alongside the International Olympics Committee), does not allow cyclists to add any device to their bicycles whose sole purpose is reducing wind resistance. Wheel covers, which can be added to spoke wheels to make them perform like disc wheels, are prohibited for this reason. This rule does not apply to actual disc wheels, however, since they also serve to propel the bike. This distinction frustrates some cyclists who prefer wheel covers because they are cheaper than buying a new set of wheels. Additionally, some prefer wheel covers because they are compatible with power meters, which some cyclists use to pace themselves. Power meters don’t work with disc wheels.

UCI rules require spoke wheels for any mass start event on the road (a race in which a bunch of cyclists all start in the same place) because they’re safer. This is because spoke wheels allow for easier recovery if cyclists bump into each other; with disc wheels, even small jostling motions tend to get magnified and may cause a cyclist to fall over. At the Tour de France, for example, disc wheels are allowed for time trials, and some cyclists use them when conditions are favorable, but they are not allowed for the mass start.

Olympic cycling teams take technological advances very seriously—one cycling medalist reportedly rode without clothes in a wind tunnel to help design more-aerodynamic uniforms—and some teams can be highly secretive about their equipment. After taking home eight gold medals in Beijing, the performance director of the British team said they shredded their uniforms rather than risking the chance that their competitors might get hold of their secrets.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.

Explainer thanks Shawn Farrell of USA Cycling.

Read the rest of Slate’s coverage of the London Olympics.