I was visiting Los Angeles a while back when a friend invited me to the boxing gym he trains at. I’d never boxed before and I love to experiment with new sports. Plus, the gym, Wild Card Boxing, is semi-legendary. It’s run by superstar trainer Freddie Roach and it’s where former “Fighter of the Decade” Manny Pacquiao frequently prepares for fights. (Pacquiao’s been training there for his match this weekend against the undefeated world champ, Floyd Mayweather.) I decided it might be fun to check out the scene.

We went on a weekday afternoon, when Wild Card was sparsely populated with a few 19-year-olds hoping to become the next Pacquiao and a few 40-year-olds hoping to shed their love handles. My friend, Mike, introduced me to his trainer, who gave me a rudimentary lesson on proper stance and then had me throw some air punches. He snickered at my form in a gentle way. I observed myself in the wall-length mirror—stiff, tentative, frequently off balance—and I couldn’t help but snicker too.

I was nowhere near ready to engage in actual boxing, which was fine by me. The trainer just had me jump rope or do crunches and pushups. I donned borrowed gloves to hit the heavy bags that swung from the ceiling. It was a terrific workout, and more interesting than plodding on a treadmill. I came back several times over the next couple of weeks, whenever Mike invited me.

Photo by Harry How/Getty Images

The day before I was to fly back to New York, Mike took our trainer aside toward the end of our session. I’d been asking Mike a lot about what it felt like to square off against a human being instead of a lumpy leather bag. Mike decided I needed a taste before I left. So he pleaded with our trainer to let us spar, just a little. The trainer was reluctant. But he agreed to let us throw a few punches—so long as everything was choreographed. We’d be going half-speed and we’d know exactly what was coming.

I slipped on puffy headgear and a pair of gloves, and stepped into the ring. I faced my friend and assumed my dopey stance. And then, at our trainer’s command, I looked Mike dead in the eye and launched my fist at his head.

There was no real contact that day. No damage. We parried each other’s telegraphed punches for a while, then touched gloves and climbed out of the ring. As Mike gave me a ride back to my flat, he asked me what I thought. I confessed that the moment when I’d thrown that first punch at him had been among the strangest, most exhilarating experiences of my life. And then I told him I was going to find a boxing gym in New York.

* * *

I’m blessed to have suffered very little violence in my life. I got into a playground scrap in fourth grade. I was mugged on Halloween by some teens from another town when I was in high school, and endured a black eye. I broke up a few drunken party fights in college, once tumbling off a porch within a scrum of flailing bodies. I also used to hang out with a person who—under the influence of various chemicals—would once in a while become unhinged and rageful, all wild eyes and threats of physical harm. I stopped hanging out with that person.

Myself, I’ve never harbored an urge to beat anybody up. In that instant before I first unleashed my fist at Mike’s face, I could sense myself struggling to punch through millennia of human social compacts, years of conditioning from my parents and teachers, and, not for nothing, the deep-seated pacifism (you might term it “wussiness”) that dwells within me.

Yet by the time my arm extended and Mike casually batted away my glove, it had already stopped seeming weird. As I was firing off my second punch, I saw how natural it felt. How genetically equipped we are to hit things. The act of throwing a punch felt not just normal but even, I realized with some disquietude, fantastic. It tingled dark, submerged tendrils curled inside my brain.

And now I’m forced to complicate my earlier claim. It’s true that—except for maybe once or twice in my life, under extreme circumstances—I’ve never wanted to hit an actual person. But at least once a week, or maybe more, I do want to hit.

When I get upset while thinking about my work, or about dating, or about that idiotic comment I made last night at a cocktail party, an impulse surfaces. It’s an impulse to slam my fist against something hard. It almost twinges my bicep, the compulsion is so strong.

I very rarely indulge it. I absolutely never do when anyone else is looking. But I can’t pretend the impulse isn’t there.

I know I’m not alone. You’ve seen it. Highway drivers smacking palms against steering wheels. Baseball pitchers punching dugout walls. Children throwing plastic toys at their mothers’ faces.

You feel it too. I’ve asked around. Every male friend I put the question to admitted that, yes, during moments of deep frustration, they want to hit things. Most, though not all, of my female friends said they’ve yearned to hit things too.

What an odd, counterproductive desire. There’s a wide disconnect between, say, the cerebral problems I face in my job and the physical solution of whacking my fist against a table. It’s no solution at all. It makes nothing better. Anyone who knows me would say I’m not an especially angry person. Yet I can’t tell you how many times—dealing with a story that isn’t coalescing, that’s bumping up against my limitations as a writer—I’ve felt an itch to chuck my laptop against the wall.

Throwing a punch at a real human being tapped into these feelings in a way I hadn’t been expecting. They’re feelings that, as Homo sapiens, we’ve got baked into our DNA. No, they aren’t a part of my surface life, or of the surface life of anyone I know. But they are there. Underneath. I wasn’t ready to stop exploring them.

* * *

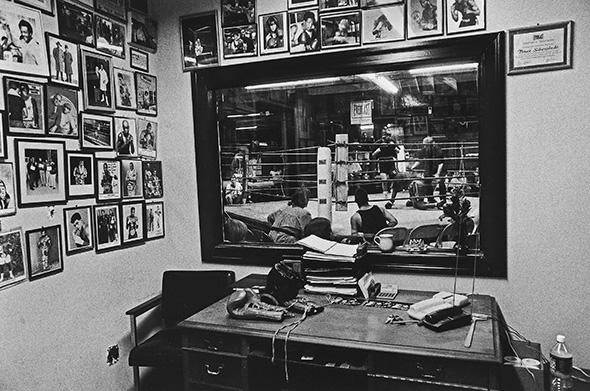

Gleason’s Gym has been at the center of the New York boxing scene since 1937. Jake LaMotta, Muhammad Ali, Mike Tyson, and dozens of other boxers have trained there over the decades. It’s been the backdrop for countless movies and television shows. Its current location, in the DUMBO neighborhood of Brooklyn, is also a short bike ride from my apartment, which sealed the deal.

Photo by Thierry Gourjon

I scanned the Gleason’s website to find a trainer, not quite knowing what I was looking for (except that I wasn’t ready to pay top dollar for a famous name). Something about Shawn Raysor’s ad jumped out at me. Maybe it was his amber-tinted sunglasses. Maybe it was that he listed his hourly rate as “recession workable.” Maybe it was his claim that he was “Old School & New School” and a “Trainer of lions, tigers, & bears.” I emailed him, and we arranged to meet at Gleason’s on a weekday morning.

There is no flash at Gleason’s. It’s all cement and peeling paint, and the air smells like the rancid hand sweat that oozes from the insides of boxing gloves. People wear gray sweats and stained white T-shirts. I couldn’t find Shawn, so I sat on a bench next to one of the raised boxing rings, watching the two men inside stalk each other in circles, hurling their fists and then slumping into exhausted hugs.

Shawn showed up 20 minutes late, shambling into the gym, apologetic. He was gaunt and stooped, shuffling and raspy-voiced. He immediately told me to jump rope. When he thought I’d jumped enough, he sent me into an empty ring to shadowbox, examining my form. After a while, we moved to pad work. I put on a pair of gloves, and Shawn slipped flat, padded mitts onto his hands. He held them up to show me where to punch. He led me through simple combinations—jab, jab, straight right; jab, straight right, left hook. He’d lightly smack me with a lightning-fast mitt to demonstrate when I was leaving parts of myself exposed. It was shocking the first time he did it. I jumped back and curled up, completely unaccustomed to having someone unexpectedly hit me.

When an hour was up, he sent me home—sopped in sweat, hands on hips, doubled over—and told me to come back tomorrow. So I did. A couple of days later, I came back again. I kept coming back, twice or thrice a week, for months.

Everything in boxing is three minutes on, one minute off. That’s the interval of the rounds in a bout, and that’s how you train. The electronic bell high on the wall of the gym counts out these rounds, one after another, all day long until the gym closes for the night. When the bell sounds to open each round, the gym fills with the clicking of jump ropes, the thud of gloves hitting pads, and the thappita-thappita of the little speed bags that hang like figs. When the bell sounds again, there is a minute of relative peace. And then comes the ding that launches us back into three minutes of fury.

It’s all supremely humbling, at the start. Things you might think are easy are anything but. Have you tried to jump rope for three minutes straight? You figure it can’t be difficult—little girls on sidewalks do it. And then 45 seconds in, you’re panting and your legs are tangled in the rope and your heart is like a drumroll.

Or try holding your fists up next to your cheeks for three minutes, without a break, like you’d do in a fight. Go ahead, try it at your desk. Maybe grab a stapler in each hand to simulate the weight of boxing gloves. Don’t dare let those hands drop before the round is over—that’s how you get clocked across the jaw. Every time your elbows sag, hear Shawn’s voice in your ear: “Hands down, man down.”

At first, I’d get comically tired after a few rounds of activity. Slowly, though, I became fitter. And then fitter. The workouts were more intense than anything I’d ever done for a team sport. They needed to be. You don’t want to get punched in the stomach if you don’t have abs like a flagstone patio. You can’t fight back if you’re breathing too hard to throw a punch.

Not that I was fighting anybody yet. I wasn’t permitted to spar. Shawn said I wasn’t ready. “We’re doing LSD, baby,” he said with a smile. “Long. Slow. Drive.” (Much of Shawn’s instruction came couched in similes involving either drug use or sex. For instance, he showed me how to properly hit the speed bag by miming a hand job. “Like when a chick is jerking you off, Seth.”)

The more time I spent training, the more I longed to face off against another fighter. It was like practicing tennis drills for six months straight without ever playing a set. I ached, to a degree that made me uncomfortable, to learn what it’s like to solidly connect with someone else’s cheekbone. I hankered—and this seemed far more perverse, but I could not deny it—to feel what it was like to absorb a hellacious punch to the gut.

At some point I saw a notice advertising a fantasy boxing camp run by Gleason’s. It was a four-day weekend in the Catskills, held at a resort hotel. There’d be lots of current and former pro boxers on hand to train me. There’d be lots of sparring with fellow amateurs. On the final night, according to the brochure, they’d match me up against another camper for a three-round bout—complete with an announcer, a referee, and a trainer in my corner.

I signed up. It was a month away, but already I had butterflies. When I told Shawn my plan, and asked him to help me prepare, he seemed to think the whole thing was silly. But he went with it. “We’ll get you ready, baby,” he said. “You gonna whup somebody’s ass, Seth.”

He started pushing me harder to build my cardio. He began to smack me more fiercely during our pad work when I left my chin out, getting me used to being hit with force. A few days before the camp began, not wanting me to get up there without having popped my cherry, Shawn at last agreed to let me climb into the ring against a few of his other clients. My first opponent would be a smiley, slender, South Asian yuppie named Vik.

The instant the bell rang to start our round, I waded directly into a flurry of Vik’s punches. I had zero plan and instantly forgot everything Shawn had taught me. My headgear got knocked sideways across my face, so I couldn’t see. Still I kept trudging into Vik’s onslaught. I was nothing but chaos and adrenaline. I was nearly hyperventilating. Shawn eventually yelled at me to fall back and take a timeout.

Vik was in awe at my blend of intrepidness and incompetence. “For a rookie, he can take a punch,” he marveled to Shawn, as I wheezed and coughed and straightened my headgear with my gloved paws.

I sparred a few more rounds that night with some of the other dudes, all relatively athletic and all with more experience than me. I settled in a little, and even landed a few solid hits. But each exchange of punches remained a blur. And I came out on the wrong end of almost all of them. On the subway home, I discovered that the side of my abdomen was throbbing with pain, like I’d been stabbed. It was a spot where I’d taken a hard hook to the body. It stung way worse than I’d thought it would. My feelings about the fantasy camp began to drift from excitement into apprehension.

* * *

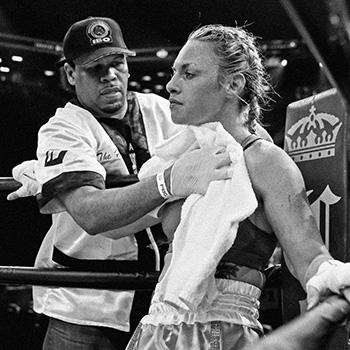

Photo by Elsa/Getty Images

“I don’t just want to hit them. I want it to hurt,” said Heather Hardy, a pint-size pro boxer, instructing us in the nuanced art of doling out damage on the first day of camp. “I want them to be scared of my hands,” she said. As a group of us stood in a circle on an empty indoor tennis court, she used me as a dummy, demonstrating how she might punch my flank—not a wild lash but rather a targeted strike up under my ribs so as to inflict maximum organ discomfort.

The pros and ex-pros at the camp showed a level of innate athleticism that instantly distinguished them from regular campers. Hardy could flit around like an electron—there was zero chance you’d lay a glove on her. Juan Laporte, a former world featherweight champ, was built like a cinder block but moved like an octopus. Even Iran Barkley, a middleweight and light-heavyweight world champ in his prime but now hulking and potbellied, still floated around the camp with the smooth grace of a placid whale.

We campers were less silky in our movements, but made up for this with flaily enthusiasm. We came from all sorts of backgrounds. Evan, by far the most talented and experienced among us (he’d been sparring every week for a long time, and was confident in the ring), was a 34-year-old music video director from New York with tattoos on his arms and neck. Jeanine, in her 50s, was an attorney from St. Louis who did amateur matches on weekends. Al had been on a path to become a pro boxer until he quit the sport at age 26 and went into the lingerie business to earn more money. At 66, he made a comeback, doing local amateur fights. At one point he got his occipital bone broken by a 21-year-old. “He swung at me after the bell,” said Al at dinner in the hotel one evening, still looking raw about it. “Al’s style is that he would come right at you like a freight train,” said his wife, looking at her husband the way a teenage girl looks at the varsity quarterback. “The kid was scared of him.” Now in his late 70s, Al still comes to the camp but mostly referees.

Photo by Thierry Gourjon

Boxing is not about self-defense. (If that’s what you need, you’re better off with krav maga, the brutal Israeli combat technique that’s the choice of security professionals everywhere.) There is, to be sure, a balletic elegance to boxing, and a strategic complexity that rewards the perceptive fighter. But you can also find these elements in sports that don’t involve beating the shit out of another person. What draws the recreational boxer to the ring, and to this camp? Why would these folks wish to spend a long weekend, and a couple of thousand bucks, learning how to better bludgeon human skulls?

Al told me that as he entered his 60s, “I felt like I had something to prove to myself,” and so he got back into fighting. More than one of the male campers mentioned that he’d been bullied as a kid, and ever since had been obsessed with the idea of feeling tough and invincible. Dave, a sales guy in his late 30s, said it was about “getting stuff out”—after punching a heavy bag for an hour at the gym, he was much more relaxed, at least for a little while. When I asked Jeanine the lawyer, she seemed to be most enthused about how strong the training made her body. But she did brag about how thrilling it was to be in the ring facing off against other women.

The camper I grew closest to, over meals and between training sessions, was a 65-year-old, white-haired, Upper West Side clinical psychologist named Scott. He and I were fast friends. We both enjoyed talking about the more atavistic, emotional nuances of the sport. Scott told me he does “rage work” with his psychotherapy patients sometimes, letting them physically express their anger by, say, hitting a pillow.

Photo by Thierry Gourjon

In time, Scott disclosed to me that he’d been violently abused in his youth. He still had “body memories” from his early childhood—they were all deep dread. He’d come to the camp for the first time last year. When he got into the ring for his assigned fight, it brought up all sorts of unresolved turmoil. “The depth of the terror and the way it took over my body startled me,” he told me. But he came back this year to do it again.

* * *

On day two, the instructors decided to throw me into the ring for a round to get a sense of my ability level, and to start figuring out who they might match me up against for our marquee fight the following night. “Are you ready for this?” asked Terry Southerland, the former pro who would be in my corner for my match.

I peered into the ring that had been set up at one end of the tennis courts. My opponent for this diagnostic sparring session would be Sonya Lamonakis. She is currently the women’s world heavyweight champion of the International Boxing Organization. She is 5 feet 7 inches tall and weighs 215 pounds. She’s built like a tank. A very ornery tank. I was most definitely not ready.

Photo by Thierry Gourjon

“We’re just playing around, we’re not gonna kill each other,” said Sonya as we touched gloves. She must have noticed the abject terror in my eyes. The bell rang, and I tried to remember everything I’d learned—the combinations, the techniques. Sonya let me throw punches at her for a while. It took me about 10 tries to land a glancing blow. “Good job,” she said. Then she fought back.

Have you ever been whapped really hard in the head with a thickly stuffed pillow? Imagine that times 30. That’s what it feels like when a 215-pound world champ punches you in the temple while you’re wearing protective headgear. I really did see the proverbial flashbulbs. I tried to parry her next punch, but I was already too dazed by the first to accomplish anything. And her hands were so fucking fast. I couldn’t tell where they were coming from. She kept hitting me. The ring felt tiny. I wanted to run, but there was nowhere to go, and besides, I didn’t want to look like a coward. Fear built and swelled inside me. I didn’t have much experience with feeling physically threatened by another person, and the rush of chemicals and emotional reflexes was overwhelming. I prayed for the bell to ring.

Back in my room after, showering off and getting ready for dinner, I felt spacey and sluggish. I’d developed an atomic headache. My ribs ached. I kind of wanted to get in my rental car and drive home right that second. Skip the rest of the weekend. Never set foot in a boxing ring again.

The next morning at breakfast, when my eyes happened to meet Sonya’s in the buffet line, I felt a zap of vestigial fear in my body. It was absurd to react to her this way. All the pro boxers I met at the camp were warm and kind. And in “real life,” Sonya is very nice, as I learned over later conversations with her. She’s a public school teacher in the Bronx (thus her boxing nickname: “The Scholar”), and I was utterly safe eating eggs and toast in her vicinity. But physical violence will do that. Sonya’s fists had made me timid on a primal level.

* * *

That morning, after breakfast, we got our fight assignments. Campers like Evan, with years of training behind them, would get to fight a retired pro in true fantasy camp style. Campers like me, who’d been boxing for less than a year, got matched against other campers. I looked at the schedule sheet taped to the wall and had mixed feelings when I saw that the evening matches would pit me against Scott, my closest camp friend.

Part of me was disappointed not to be fighting a person much scarier and stronger than I was. That would have allowed me to reassure myself I’d overcome any lingering cowardice from yesterday. And it would make for a more glorious capstone to the quest I’d been on ever since I threw that first punch back in Los Angeles.

But my headache from yesterday was still throbbing. A big part of me exhaled at the thought of fighting Scott instead of a more intimidating foe. Just as Sonya’d had 40 pounds on me, I had 40 pounds on Scott. I was 25 years younger, too. I respected Scott’s boxing skills, but the sheer physical gulf between us made me much less worried that he could really hurt me. I still felt nerves, but I didn’t feel dread.

As for Scott, the whole lead-up to our match, he said later, was a miasma of anxiety. “Having done it last year gave me no insulation this year,” he told me. “If anything, the fear expanded and filled me the entire day.”

The judge and announcer for our fight night was an actual World Boxing Council official named Chuck Williams. Chuck is in his 80s. He’d at one point told me a story about how, when he was in his 70s, he’d helped a flight attendant by punching out an unruly fellow passenger on an airplane. Chuck was big on the gut-check aspects of the sport. “Anyone can get in the ring the first time, when you don’t know what to expect,” he said to me at lunch that afternoon, before my match. ‘But anyone who gets in the ring a second time doesn’t ever have to doubt their fortitude again.”

I tried to watch the early fights on the card, but I was too jittery to pay attention. One of the teenagers that had been there throughout the weekend (Gleason’s runs a program for disadvantaged children called Give a Kid a Dream, and buses a flock of kids up to the camp each year as a special treat) saw me standing alone, nervously putting on my wraps, and he offered to help. Wraps are the gauzy ribbons that you loop around your hands to protect them beneath your gloves. Kevin threaded the rough-woven fabric across my palms and over my knuckles, down into the webbing between my fingers and around my thumbs at their roots. I tried to breathe deeply and release the tension gathering in my shoulders.

And then it was fight time. Terry, my corner man, helped me step into my padded abdominal protector while he pulled my headgear down around my ears. I chomped on my mouth guard and ducked between the ropes into the ring. “Jab and move,” Terry said, miming some little combos. “You got this.”

At the bell, Scott and I strode to the middle of the ring and circled each other. We threw halfhearted jabs. We were tentative. To be honest, I think there was some profound emotional shit going on at the beginning of the fight. Scott was battling ghosts from his childhood. I had leftover demons from the whupping Sonya’d administered. There was also the unfortunate coincidence that Scott is an older, white-haired psychologist and that my father is an older, white-haired psychologist. (The Freudian complexities at play here are not something I wish to fully interrogate right now.)

Photo by Thierry Gourjon

I landed a few combinations toward the end of the round, and my movement loosened up. I went back to my corner at the bell, and Terry squirted water into my mouth from a bottle. “Keep doing what you’re doing.” he said. “You’re all over him.”

In the second round, I fought a little harder. I didn’t want to punch Scott full strength, given our size disparity, but I started to throw my flurries a little quicker. I connected with a bit more authority.

Photo by Thierry Gourjon

Then came a moment when Scott was shuffling away from me and he opened himself up, flatfooted, so that he faced me dead-on. At that same moment, I threw a straight right that hit Scott’s headgear squarely at his forehead. He tumbled backward onto the mat.

I could not believe I’d just knocked down a 65-year-old man. I rushed over to see if Scott was OK, holding my hands up in aghast apology. But with my gloves still on, I realized it looked like I was raising my fists to menace Scott as I stood over his crumpled body. Referee Al stepped in and pushed me toward my corner. “Nice!” said Terry. “You’re looking like a champ out there!”

Scott was fine. He’d been knocked off balance, not knocked silly. Still, I pulled my punches in the last round. I used proper technique, and I looked for openings, but I tapped Scott instead of hitting him. Any fear or panic present earlier in the weekend had ebbed away. It was replaced by a rising tide of guilt.

Photo by Thierry Gourjon

* * *

The next morning at our final breakfast before heading home, Heather Hardy complimented me on my performance. “You looked pretty good out there,” she said, and there was general assent from other people at the table.

“I don’t feel great about it,” I said, looking around to make sure Scott wasn’t near enough to hear me.

“Why? Because he’s older than you?” asked Terry. “He got in the ring. He was throwing punches at you. He knew the deal. If you want, I’ll find you a 65-year-old man who can beat your ass. There’s plenty of ’em.”

Scott bore no ill will toward me. We had a nice talk before we parted ways, and we exchanged contact info. He said he planned to come back to the camp again next year. It was an ongoing journey for him.

Not for me. I was done.

A few days after I got home, Shawn texted me to ask how it went and to see if I wanted to schedule another training session. I told him I needed to take a break for a while. I said I’d get in touch with him in a couple of months.

By the time I did, Shawn had died. He’d had brain tumors, it turned out, and his health fell apart quickly. I didn’t know he’d passed until I saw it on Facebook through one of his other clients whom I’d trained with a few times. I wished I’d been able to see Shawn once more. I’d have liked to buy him a drink so I could thank him. He’d prepared me to fight as well as anybody could have. If he’d asked me why I wanted to stop boxing, here’s what I would have told him:

I loved the choreography of the movement and the flow of combinations. I loved how strong and fit I’d become—at 40, amazingly, I was in the best condition of my life. I loved the camaraderie after a sparring session or a fight, when you’re all jazzed on adrenaline and eager to dissect every punch and counterpunch.

I don’t, however, want to get hit in the head, which I worry will deaden my brain. I don’t want to get hit in my gut, which aches for days. More than these: I don’t want to feel fear. I don’t want to impose fear on others.

That urge to violence I feel when I’m frustrated, that twinge in my bicep, that abstract desire to hit: It hasn’t left me. If anything, I now picture hitting things with better form. With more specificity to my technique. My savage urges have taken on martial discipline, but are as emotionally incoherent as ever. I asked a psychologist my dad put me in touch with—a guy named Brad Bushman who studies this stuff—whether boxing was a good way to help vent these feelings or whether it simply gives them more tangible expression. “Boxing to reduce anger is like using gasoline to put out a fire,” he wrote me in an email. “It just feeds the flame.”

I still do the workouts Shawn taught me. I still shadowbox to stay fit and limber. I will be watching the Pacquiao-Mayweather fight with elevated interest—observing the rounds unfold with more insight and empathy than I would have before I’d tried boxing for myself.

But I doubt I’ll ever throw another punch at a person. Not if I can help it. I don’t have anything to prove.