In his rumination on the importance of archives at online publications such as Slate, Nathan Heller pondered the meaning of the past at a magazine that leaves “no paper trail at all.” As always, Heller’s insights were perceptive and thought-provoking, but a handful of unprepossessing volumes sitting on my bookshelves force me to challenge the notion that Slate has never had an offline incarnation. For the first few years of its life, Slate offered a print version known as Slate on Paper.

Today if you ask someone “Are you online?” you’re inquiring if they’re sitting in front of a computer or can access the web on their smartphone right this second. Back in 1996, though, it meant “Do you have access to the internet in any form whatsoever?” For many people the answer was, “No” or “Barely.” And even for folks who had an on-ramp to the information superhighway, reading online for pleasure was a new and vaguely suspicious activity. Indeed, one of the reasons Microsoft created Slate in the first place was to encourage people to look to their computers for reading material other than stock prices or movie times.

Starting in September 1996, a monthly version of Slate on Paper was available at selected Starbucks locations for $3 per issue. As Michael Kinsley explained, this publication was intended “to serve readers who can’t access the web.” This best-of-the-web digest was short-lived, but SoP, as those of us who painstakingly pulled it together every Friday morning always referred to it, had a surprisingly long life, existing in one form or another until January 2005.

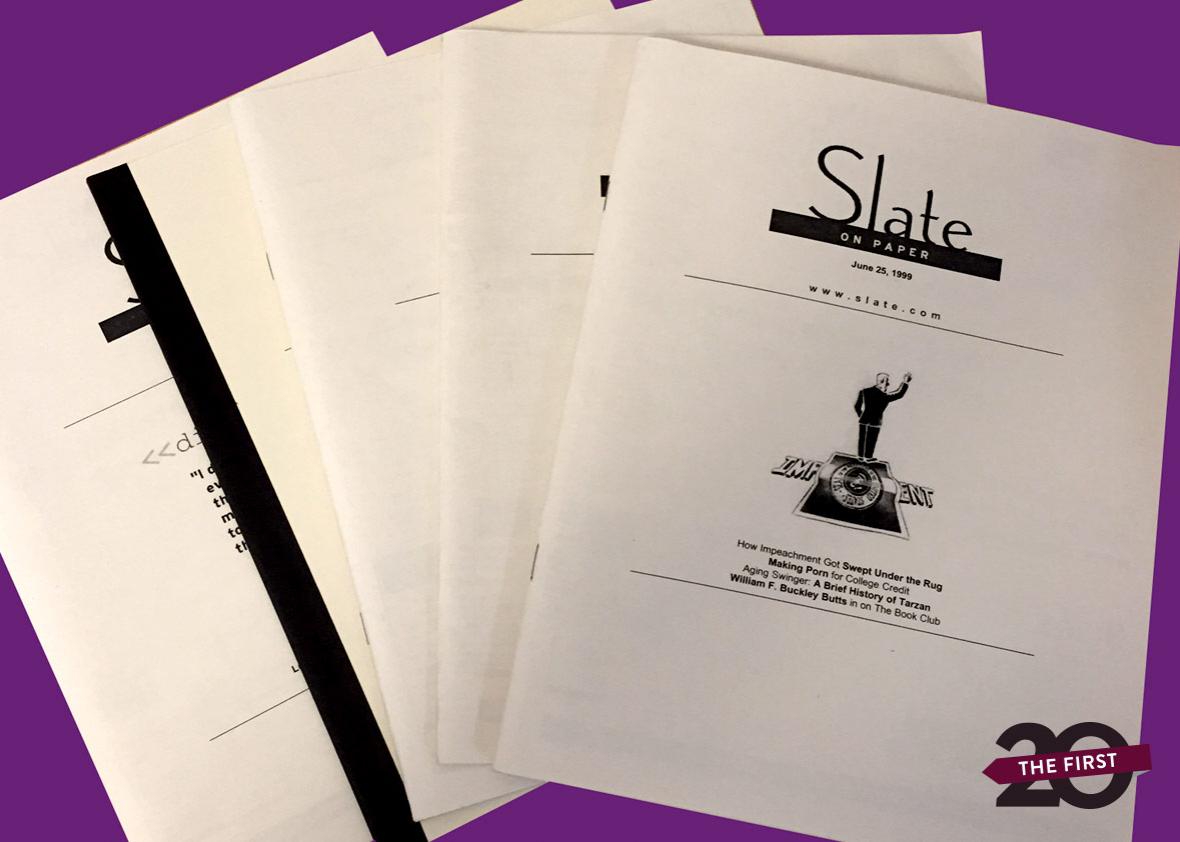

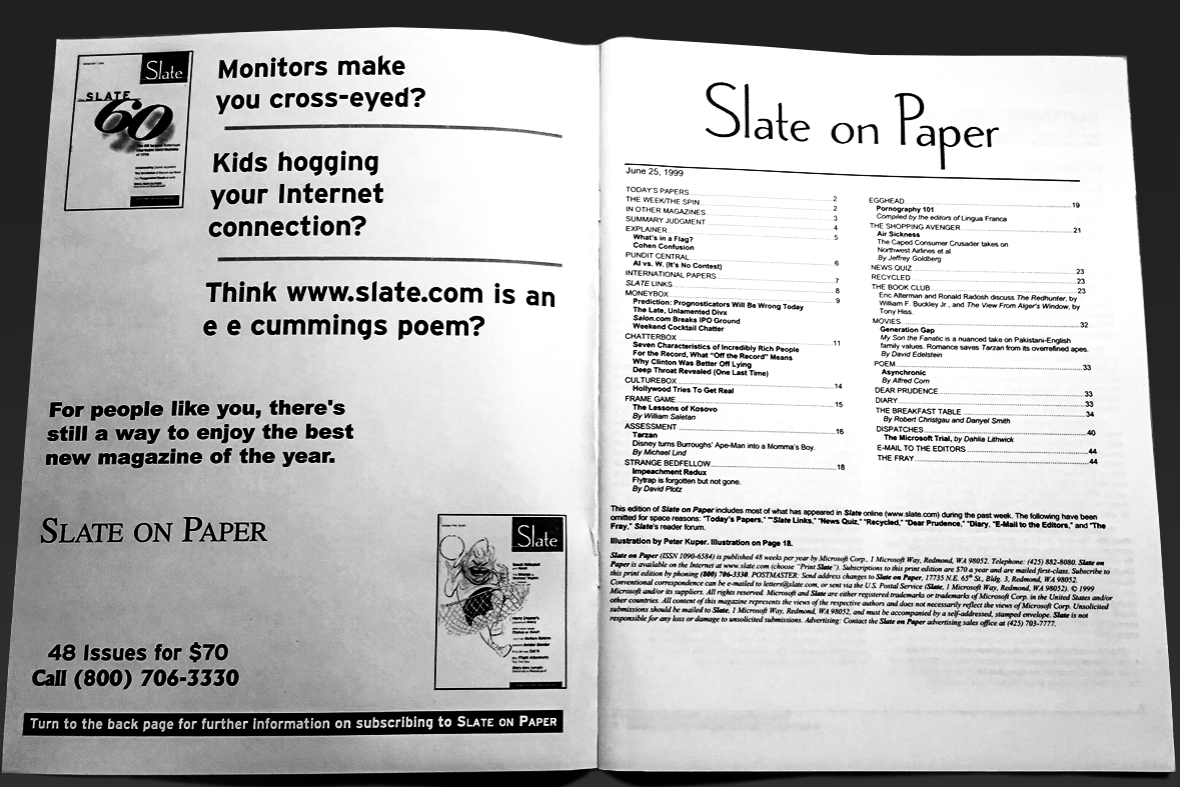

When I think of Slate on Paper, I see its most iconic form—a stapled 8.5-by-11–inch booklet whose lo-fi black-and-white cover bears the Slate on Paper logo, the date, Slate’s URL, a small illustration, and four short cover lines. The contents of the back and inside covers never changed, and thus they became invisible to regular readers like me. Looking at the inside front cover of a June 1999 issue now is like looking at a cuneiform slab, so strange are the words. Enjoy, please, the sales pitch that can be found there:

Monitors make you cross-eyed? Kids hogging your Internet connection? Think www.slate.com is an ee cummings poem? For people like you, there’s still a way to enjoy the best new magazine of the year. [Um, of three years earlier, but never mind.] SLATE ON PAPER, 48 issues for $70. Call (800) 706-3330.

Slate on Paper looked like something an adolescent could create at their local copy shop, which is appropriate. Every Friday morning, the copy editors—all based on the Microsoft campus in Redmond, Washington, in those early years—would get to work before 7 a.m. so we could pull together a comprehensive compendium of the week’s stories. The night before, we’d spend a few hours rereading everything we’d published over the course of the week (this was the fourth pass in most cases), and on Friday, we’d fix all the problems we’d spotted in our overnight scrutiny and add the morning’s new stories. Then we’d send the resulting Word document to the Microsoft copy shop, which would duplicate it, bind it, and ship it off to subscribers.

I won’t deny that I sometimes complained about those early-morning fire drills. It seemed silly to go to such lengths to put out a version of the magazine that very few people ever saw—perhaps to save our sanity, we were never told exactly how many people were on the subscription list. Nevertheless, we enforced the Slate on Paper deadline with extraordinary rigor, no doubt to the chagrin of writers whose pieces ran on Fridays. We considered the SoP version to be the ultimate iteration of the week’s copy—if a writer asked to make a change after Slate on Paper had gone to press, we’d brush them off with a firm, “No!”

In those whiny before-breakfast Friday mornings, we often blamed William F. Buckley Jr. for our early start. Somehow, he had come to stand in for the sort of older journalistic eminence who was too stuck in his ways to read Slate on-screen, as God—well, Gates—intended, and thus needed to receive the word in printed form. (This was grossly unfair to Buckley. In the June 25, 1999, issue, he jumped into a Book Club discussion of his novel about Joe McCarthy in time for his intervention to be included in Slate on Paper, so clearly he paid close attention to the website.) SoP also went out to a select group of Microsoft executives. If I’d had a lick of sense, this alone would’ve stopped me from complaining—those were people who had the power to decide the magazine’s fate—but I was young and foolish.

The Word doc that went out to the Microsoft print shop was also sent out as an email attachment to readers who subscribed to the Slate on Paper newsletter. If you search the Slate archives for “Slate on Paper,” you’ll find a surprising number of references in Readme, Michael Kinsley’s column. Mike was a little obsessed with letting people know about the profusion of ways people could read Slate—including, he once wrote:

Slate inscribed on a loaf of bread; Slate beamed into your head while you sleep; Slate recited to you by Ralph the talking dog; Topiary Slate (Slate articles carved into your shrubbery); Slate-by-Massage (“Moneybox” communicated through seven secret pressure points on your body—subscribers only); the Slate Ballet (“Keeping Tabs” reinterpreted for the dance); the Emperor’s New Slate (we pretend to publish it, you pretend to read it—subscribers only); and much more.

Given what I must admit is a bad attitude to Slate on Paper—oh for the Thursday nights I could’ve spent watching Must See TV and the Fridays when I could’ve stayed in bed past 5 a.m.—imagine how surprised I was to find the 17-year-old copies of Slate on Paper that were sitting on my shelves utterly delightful. I have no idea how the five copies still in my possession survived the great paper purge that preceded my move across the country in 2005—utter randomness seems the likeliest explanation—but flipping through them now is a wonderfully evocative experience that makes me realize how contextless online reading can be.

Take, for example, that June 25, 1999, issue. After 14 pages of what we used to call “Briefings”—quick takes on the news in The Week/The Spin; summaries of the stories In Other Magazines, International Papers (my column), a recap of the weekend talk shows in Pundit Central, and a couple of Explainers—come the “boxes”: Timothy Noah’s Chatterbox, James Surowiecki’s Moneybox; and a Culturebox by Daniel Menaker. Then William Saletan Frame Games the lessons of the Kosovo war; Michael Lind pens an Assessment of Tarzan; David Plotz looks back on Flytrap (Slate’s nickname for the indiscretions that led to Bill Clinton’s impeachment); the staff of Lingua Franca round up the latest academic skirmishes in Egghead; and the Shopping Avenger—how could I forget that Jeffrey Goldberg was once the consumer’s friend?—battles Northwest Airlines on behalf of a Slate reader. Around the staples comes that Book Club in which Buckley swipes back at Eric Alterman and Ronald Radosh; David Edelstein reviews My Son the Fanatic; and Robert Christgau and Danyel Smith discuss the news in the Breakfast Table. Finally, Dahlia Lithwick files four dispatches from the Microsoft Trial. (That wasn’t actually everything we published that week—it was as much as we could squeeze into 44 pages—but we listed all the departments that hadn’t made the cut.)

I don’t think I’d hurt anyone’s feelings by suggesting that none of those stories will appear on their author’s greatest-hits lists, but flipping through Slate on Paper was still extremely pleasurable. Also, I am now fully prepared should “events of the week of June 25, 1999” ever turn up as a category on Jeopardy!

It was oddly comforting to hold a week’s worth of Slate in my hands—a lot of work went into those 44 pages. But it was the contents of a little box at the bottom of the last page that convinced me we’d lost something by letting go of SoP. It contained the names of the staff and contributors who worked on the magazine at the time. Sure, we still have a masthead, but it only shows the current team. There’s no record of mastheads past—except in the few remaining copies of Slate on Paper.