To celebrate Slate’s 20th anniversary, and to get some purchase on the 152,734 posts in our archive, we asked the current staff (and a few old friends) to pick stories from our past: the best, the most memorable, or just the Slatiest. Here’s how they responded.

L. V. Anderson, associate editor

“Against Pepper,” which Dan Engber edited a couple of months after I started at Slate, is such a perfect Slate pitch: as ultimately persuasive as it initially seems absurd. Just look at that dek: “Salt needs a new companion.” How could you not click? (I still use lots of pepper, but I think about this piece a lot.)

Jeffrey Bloomer, associate editor and video producer

A classic Slate pitch, before that was a hashtag pejorative: Oysters are plants, ethically, so vegans should feel free to eat them. Christopher Cox’s premise may seem like a needless provocation, but with his breezy guide to veganism and the latest in bivalve pain research, he offers a surprisingly profound argument in an age of overblown rigidity in our diets. Years later, vegans and meat-eaters alike still argue about the happy-hour mollusks in the comments.

Torie Bosch, editor of Future Tense

I’ve been at Slate in various capacities since I started as an intern in the fall of 2005. But one of my favorite pieces of Slate arcana predates me. It’s the Webhead (a long-defunct Slate rubric) that Daniel Engber wrote in June 2005 about his efforts to win a “contagious media” contest. Crying, While Eating, the site Dan and a friend created, quickly became a front-runner. It’s exactly what it sounds like—videos of people crying about all manners of things, while chowing down. The piece is a fascinating look at the seeds of today’s viral-content economy. (The contest’s “host” was Jonah Peretti, who went on to found BuzzFeed.) Dan describes watching Crying, While Eating attract attention from both mainstream press and porn sites—and he even ended up on Leno. After the late-night host learned that the site wasn’t turning a profit, he asked how Dan and his friend paid the bills. After learning Dan wrote for Slate, Leno responded: “Slate magazine? Well, that probably doesn’t pay a whole lot either.”

Christina Cauterucci, staff writer

Something about Nicholas Kristof’s New York Times column has always made me feel icky, and until this 2014 piece by Amanda Hess, I’d never paused to consider why. Hess laid it all out—Kristof’s white-savior complex, his eagerness to buy into too-perfect stories that often turn out to be false, his focus on short-term solutions that only affect one person instead of addressing systemic issues. But Hess also gave a detailed history of his career arc and an honest assessment of his knowledge and impact, neither of which are negligible. For me, the article exemplifies this online magazine at its best: It’s a place where pointed skepticism and criticism don’t have to get in the way of reporting the nuanced truth.

Daniel Engber, columnist

Two memorable pieces from 2008, both researched in large part by Slate all-star Nina Rastogi and her army of interns. Both of these were interactives, but the interactive components of the second have since turned to dust.

“80 Over 80”: This was Slate’s response to those “40 Under 40” lists that always get published in magazines like Forbes and Fortune. We decided to rank the 80 most powerful, influential and energetic octogenarians in America, along with a selection of hot 79ers who seemed destined to make next year’s list—and managed to keep this going for three years in a row. I remember that we took some heat in 2009 for including white-supremacist leader James von Brunn, who, at just a month shy of his 90th birthday, murdered a security guard in his terrorist attack at the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C.

“Procrasti-Nation”: This was Julia Turner’s idea, and the anchor for our special issue on procrastination: We interviewed people from every profession we could think of about how they tended to waste time on the job. What does a butler do when he’s procrastinating at work? What about a CIA agent? An NFL cheerleader? A clown? My favorite was the chimney sweep: “I often get carried away with the explanatory part,” he said, “chitchatting about how chimneys work to avoid the pipe.”

Jocelyn Frank, podcast producer

Do you know that moment in your day when you realize you’ve been netted into a reply-all-email-fest that is due to go on and on? Dan Kois made that one of the best that I’ve had at Slate when he asked staff (and contractors) to weigh in on what animal we’d resign ourselves to transform into à la The Lobster. The replies punctuated the day with witty and bizarre flashes of entertainment, and I learned more about my colleagues than one could ever garner from a trust fall. Thanks, Dan.

Ruth Graham, contributor

“Smoke and Mirrors” made a huge impression on me when I read it back in 2003, long before I had written a word for Slate, and I still think about it often. It starts with a shibboleth—firefighters are heroes—and goes on to dismantle it with terrifyingly cool efficiency. It’s a juicy idea that begs to be debated, but it’s also so tightly argued that dissenters are doomed.

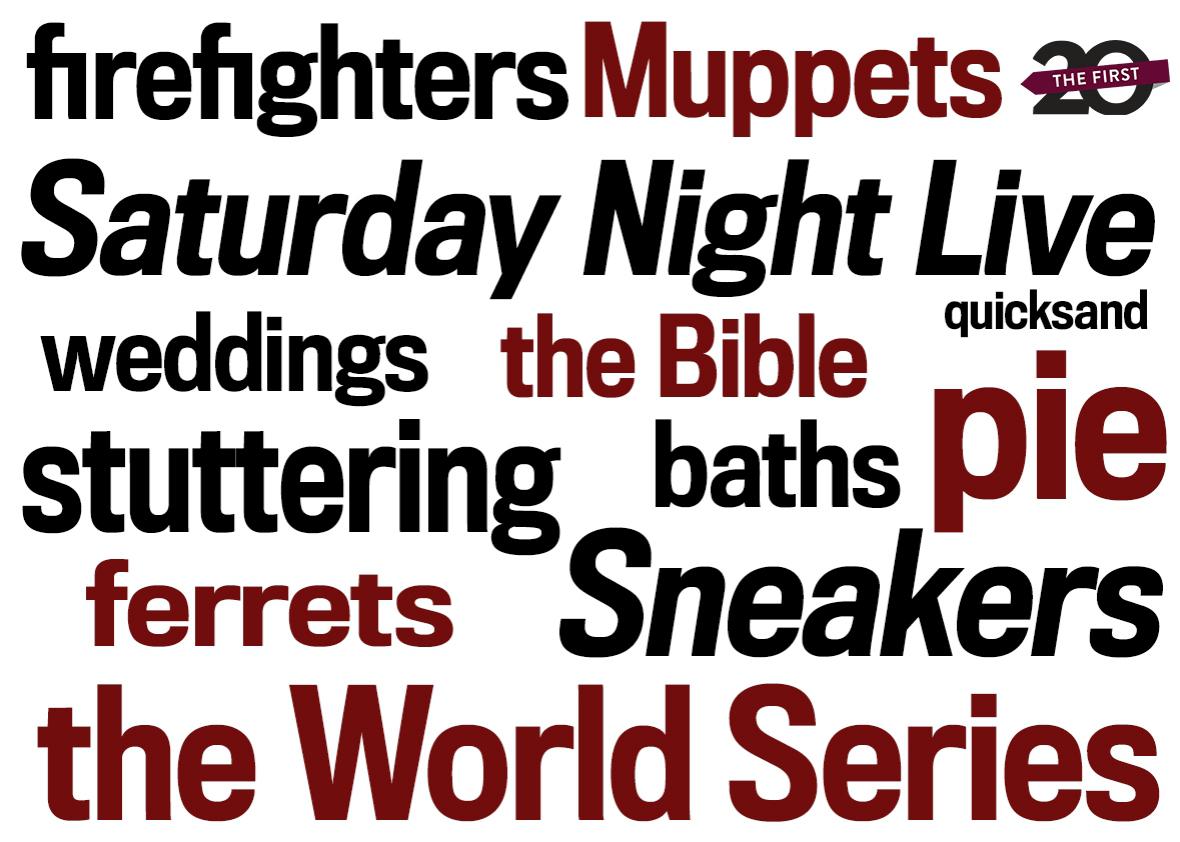

Aisha Harris, culture writer

I will never forget how Dahlia Lithwick’s Muppet theory put my entire life into a new perspective. Forget ENTJ/ INFP/blah blah blah—it doesn’t have to be so complicated. You’re either a Kermit or a Cookie Monster, a Sam the Eagle or a Gonzo. Diagnose yourself and then accept it. I did, and now I know Beaker is my spirit Muppet.

Nathan Heller, former staff writer

About a year and a half into my time at Slate, a brilliant young writer named Jonah Weiner, now of Rolling Stone and the New York Times Magazine, wrote an 1,100-word piece that has become famous—maybe infamous—as an extreme point on the Slate worldview. The piece was titled “Creed Is Good.” It is worth parsing this headline word by word, to show what made it so extremely Slatey.

First, “Creed.” In 2009? This was, recall, a year that brought us “Single Ladies,” “Poker Face,” and “Fireflies.” Probably the magazine covered these mainstream hits; I honestly don’t remember. What I do recall is that Jonah found this the perfect moment to praise the dubious comeback of a band that all the music-journalism world, and much of the enlightened public, had dismissed as a creative cautionary tale. Why was this allowed? Because the magazine was Slate, and Jonah had an interesting case to make.

“Is.” Not “used to be,” not “might actually be,” not “could, by certain measures, be seen to be.” Arguments have always had a playful, venturesome quality at Slate, and part of the play comes from presenting them in the strongest and most confident form. Long before it was somehow considered a virtue to get onstage and say politically incorrect things, Jonah was publicly rooting for Scott Stapp as (to use his unimprovable phrase) “Charlton Heston in leather pants … obnoxiously anachronistic.” No Slate writer worth her salt has ever been afraid of getting hammered with tomatoes. Jonah, here, was gladiatorial in his daring.

“Good.” This isn’t qualified praise; it is a universal moral verdict of the sort a leather-pants–wearing ideologue might welcome. Although Jonah’s piece is nuanced, the bald headline does it no injustice. His overriding point is that Creed—this embarrassing turn-of-the-millennium schlock-rock group cobbling itself back together after an even more embarrassing hiatus—is a force for good, and deserves our interest and affection. I think of this as the final Slatey turn: Although the magazine’s arguments are scrutinous, contrarian, and sometimes even prickly, the thinking behind them aims to be generous, morally demanding, and, in the best cases, humane. Is Creed good? Maybe. But I suspect this piece is better still.

Andrew Kahn, assistant interactives editor

Amanda Hess’s piece from last year on sex panics, from the personal ads of the 1860s to the dating apps of our own age, stands in my memory as a paragon of Slatiness: funny, concise, and irrefutable.

Joshua Keating, staff writer

Long before I worked at Slate, I considered it a personal mission to expose as many people as possible to the joy that is Rob Donnelly’s animated interpretation of Rudy Giuliani completely losing his shit on a ferret-rights activist. At this point, it’s a nine-year-old video based on a 17-year-old recording, but I still lose it every time at “little weasels.”

Dan Kois, culture editor

Slate’s “Diary” feature was a home to much of the magazine’s greatest writing in the first few years; giving interesting and famous (or demi-famous) (or not at all famous but quite interesting) people a week’s worth of real estate in the magazine yielded some remarkable pieces. I particularly remember Slate’s copy editor Lakshmi Gopalkrishnan’s beautiful Diary written while visiting family in India; DJ Spooky’s nearly impenetrable combination of lyrical description and source code; and Dave Eggers’ so-arch-they-almost-make-a-complete-circle entries:

Confession: Due to budget cutbacks and constraints of time, many of the dates, numbers and names in previous Diary entries were published before they could be confirmed or corrected. Here we will set things straight:

…

Both Monday’s and Tuesday’s entries were to include coherent and digestible remarks about issues of national interest, blended seamlessly into and applicable to the narrative of the diarist’s uneventful day.

But the one I remember the best was the Diary from anonymous professor “Untenured,” who so perfectly described a day spent putting out fires and making more work for himself that I recognized his despair even though I am not a college professor:

I propose that they “sign up” for individual meetings with me this week so that we can discuss them as “drafts” and then they will rewrite them for an honest, but improved, grade. So now it is 1 p.m. and my papers are even less graded than they were at 9:30 and I have just lost eight more hours of the rest of my week.

Tell me about it, Untenured. Whose work isn’t less done at 1 than it was at 9:30?

Rachael Larimore, senior editor

David Plotz owns both an insatiable curiosity and a dogged sense of determination. During one Slate function, we engaged in such a lengthy conversation about my preferences in the 2008 election (preferences he was hoping to change) that I lost my voice and couldn’t give a presentation the next day. He brought that same energy to his self-assigned task of Blogging the Bible. In 2007, blogging was a new enough medium that employing it to discuss the Torah created a delightful contrast between new and old, and Plotz brought the Old Testament to life for those of us who were experiencing it for the first time.

Josh Levin, executive editor

Mathematician Jordan Ellenberg’s piece on building a better World Series has delighted me ever since it was published in 2004. Ellenberg sees the best-of-7 series as an algorithm and asks if there’s a way to improve it. There is, it turns out, and his explanation for how to do so is simple, clever, elegant, and won’t be adopted by Major League Baseball even if the game persists for a bajillion years.

Dahlia Lithwick, legal correspondent

Emily Yoffe’s insanely, derangedly brilliant Human Guinea Pigs got better and better. From being a lobbyist to being a mime to photobombing home shopping network QVC, everything Emily did was magic and everything she wrote about it later was quitessential Slate. Mike Kinsley’s rule was “Write about anything, but do it brilliantly.” That was HGP, every damned time

J. Bryan Lowder, associate editor

This essay on The King’s Speech and, more broadly, stuttering as a condition represents, I think, Slatey prose at its most refined. Nathan Heller manages to mix smart argument and film criticism with broad cultural commentary and the best sort of personal memoir. It’s a piece I continually come back to as an example of what good writing in this magazine should be.

Susan Matthews, science editor

(1) Lily Newman’s defense of baths could have been a particularly annoying #slatepitch, but in Newman’s capable hands it is instead a delightfully funny exploration of a personal habit that hits on the environmental implications of showers and the importance of self-care. In a media landscape where it is increasingly easy to surround yourself with ideas complimentary to your own views, open yourself to the possibility that daily baths are not disgusting. Yes, she addresses “sitting in your own filth.”

(2) Before it was the news itself that required explanation, Slate explained all manner of oddities in the world through the Explainer column. Anchored at various times by the ever-Slatey Dan Engber and Brian Palmer, it approached reader-submitted questions—sometimes mundane, often amusing—with the same aggressive reporting we would apply to more serious topics. Why does lemonade quench our thirst? How do you pronounce the Boston Marathon bombers’ names? Why do parrots swear so much? Do women find men in uniform more attractive? The questions piled in faster than Slate could reply, yielding the delightful end-of-year tradition in which readers could vote on which lingering question, of many excellent candidates, ought to be tackled. That practice delivered many gems, including the answer to the perplexing question of whether soap is self-cleansing. The archives have aged well, and are worth revisiting.

Seth Maxon, nights and weekends home page editor

In 2013, Slate ran a wedding series that I missed. Shortly after getting married last fall, I stumbled on it, and former editor-in-chief David Plotz’s piece on the friends who disappear after your big day broke my heart. Do I really have close friends whom I’ll never see again, now that the party is over? Plotz’s lucid, warm-hearted, often funny voice is practically synonymous with Slate’s at its best. Here though, it gave me the fear: Which friends will it be?

Leon Neyfakh, staff writer

Maybe it’s because of my inclination toward collecting, but the first thing I vividly remember perceiving as a trademark of Slate was the Completist – a recurring column in which various writers would swallow up and process the entire body of work of a single director or musician or author, and explain him or her to readers through the prism of a magisterial new theory. It struck me as a thrilling way to interact with culture (and it’s no coincidence, I think, that the first thing I ever wrote for the magazine was published under the Completist rubric).

I’ll embarrass him by saying so, but whatever: What made me fall in love with the column was the work of Nathan Heller, once a copy editor at Slate and now a staff writer at the New Yorker. It’s funny, because looking back through the Slate archives, I’m surprised to realize that Nate never actually wrote a Completist, and that the pieces of his I’m thinking of, the ones I remember so fondly, were actually published under the header of “Assessments.” But their spirit was very much the same; the Assessment was Nate’s personal Completist column, a space in which he could train his piercing gaze on topics as far-ranging as Natalie Portman, Lady Gaga, and pie, and tell us what they meant.

The piece that sticks out most is his take on Saturday Night Live, which taught me that my favorite TV show “came into being on the back end of the counterculture, and its role, from the start, was to safeguard the dying creative mood of that era.” Nate’s piece is so full of memorable lines that I feel compelled to restrict myself to one: “To watch 90 minutes of the program straight through as an adult is to end up feeling as if you’ve eaten half a pizza and a hefty bowl of peanut-butter M&Ms.” The piece explained to me what I liked about SNL but also why it always left me vaguely unsatisfied and depressed. Five years later, at a moment when it feels to me like the show is enjoying a renaissance, I only wish Nate was still at Slate to tell me why.

Mike Pesca, host of The Gist

In 1999 seeing your byline in print, even in the online version of print, was a thrill. No Facebook, no Twitter, no podcasts—even your email address was likely not your actual name since we were all convinced that the internet was no place for self-disclosure. One of my first interactions with Slate was as a contributor to a daily feature called “News Quiz.” Each day Randy Cohen would highlight a clip in the news, then open it up to readers to play the role of wiseacre. We’d email Randy, and the next day he would publish the best answers. (Think of a highly curated version of Gawker’s comments section, or Reddit with an extremely slow connection.) I’ll point you to a few times where my answer made the cut.

“No. 228: Still Not Sure”: This one I include because, unlike the other two, I think my answer is actually kind of funny. Also it still works in 2016.

“No. 163: Initiation”: Randy would always credit submitters whose jokes were on the same topic as the winner, but in some way inferior. This was a great lesson to an aspiring quipster, as I could surmise where I went wrong. Answer almost always: be pithier:

“No. 264: The $156K Problem”: This one I include not because my joke was that great but because of who I was surrounded by. Carvell and Radosh would go on to become writers for The Daily Show. Lerangis is a top young adult novelist, Wasik is now deputy editor for the New York Times Magazine; in 2003 he invented the term “flash mob.” Because Randy wrote for Late Night with David Letterman real live Letterman writers like Bill Scheft and Merril Markoe would submit. Sometimes thy’d win, but sometimes their contributions would be noted by a “similarly M. Markoe.”

Justin Peters, correspondent

Only Slate would spend a week celebrating the 20th birthday of an obscure Robert Redford cyber-caper from the early ’90s. And make that movie seem worth it.

David Plotz, editor-in-chief, 2008-2014

What piece ran during your time at Slate that only Slate would ever publish?

From the perspective of 2016, this is a harder question than it seems. So many pieces that Slate published 5 or 10 or 15 years ago now seem like the kind of pieces that plenty of places would be happy to publish. But that’s a tribute to us: We published stories that were transgressive or weird but have now been normalized. For example: Nathan’s attack on pie would now be an F7 feature at any number of places. Our various longform experiments, which were really early (my “Seed“ series, or Engber’s ”Pepper“), don’t feel different anymore. Our first aggregation (Today’s Papers, In Other Magazines) was new, became trite. Or the Sopranos dialogue, which pioneered close reading of TV shows, would feel banal today.

The one kind of piece I can recall that Slate did, and that really only Slate did, and no one has adopted was “How Slatesters Voted.” I think it took real guts for us to publish our biases so baldly, to own them, to let our readers and our critics revel in them.

Jody Rosen, contributor and former music critic

Slate has a reputation as willfully contrarian and “counterintuitive.” I’d use a different term: surprising. There have been so many weird, memorable Slate articles that cast the world in different light. My favorite is Dan Engber’s 2010 treatise on the rise and fall of quicksand as a cultural trope, a piece that wends its way from a fourth-grade classroom to the Vietnam War quagmire to the world of, um, quicksand porn. “Hey, Swans, how about a 5,500-word piece on quicksand, with a slideshow and infographics and audio excepts from the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech?” That, to me, is the definitive #slatepitch.

Gabriel Roth, senior editor and Slate Plus editorial director

When I was starting out as a journalist I liked to throw around terms like “off the record” and “on deep background” because I thought they made me sound grown-up. So I was startled to read this Chatterbox column, in which Timothy Noah asked five Washington Post reporters what those phrases mean and none of them could give him a straight answer. It’s a classic Slate piece because it turns over something that’s sitting right there in plain sight and finds some fascinating lessons underneath. Lesson 1: If you’re talking to a reporter, always discuss attribution issues in plain English instead of jargon. Lesson 2: Everyone likes to sound grown-up. It spurred this equally interesting follow-up, which asked the troublesome question “Why do people speak to reporters at all?”

Heather Schwedel, copy editor and contributor

(1) Before Emily Nussbaum was a Pulitzer Prize–winning TV critic for the New Yorker, she wrote for Slate, and I quoted her in a college paper. I am not implying any causal connection between these things, just bragging that Slate (and I) had very good taste. This piece about spoilers, written in 2002, talked about the way the internet’s capacity for spreading information and chatter was just beginning to affect and revolutionize serial television. My paper was about fan culture and television (this was circa 2007, so Lost figured heavily in it, I recall), and it was probably drivel, but it also created the seed in my mind that maybe one day I too could write smart things about pop culture and our changing cultural mores? Sad but true.

(2) One of my very favorite writers, Curtis Sittenfeld, wrote this piece recommending a young adult novel, The Miseducation of Cameron Post, which I probably wouldn’t have heard of otherwise but which I read and became one of my all-time favorites. How can you even properly thank someone for bringing a book or any thing you love that much to your attention? As those credit card commercials used to say, it’s priceless.

Jeremy Stahl, senior editor

“Chaos Theory: A Unified Theory of Muppet Types” is a rib-ticklingly funny explanation of a completely novel way to look at the world that is also totally intuitive, which makes it a perfect Dahlia Lithwick story. Muppet Theory is also an ideal Slate story because it takes a complex topic—human interaction—and distills it into something everyone can understand. You are Kermit, or you are Gonzo. You are you are Beaker, or you are Dr. Bunsen Honeydew. You are Bert, or you are Ernie. The world need not be more complicated than that.

Mark Joseph Stern, writer

Dahlia Lithwick’s 1999 classic ”Stripper Bingo at the Supreme Court” deftly weaves together an extremely sophisticated First Amendment analysis with amazing jokes about strippers. It is the only article I have ever read that discusses both content-based regulation of expression and pubic hair. Dahlia singlehandedly invented Slate’s Supreme Court Dispatch genre in the ’90s and quickly proved why she’s the best SCOTUS writer in the game. She’s still on top, of course, but now she has a lot more copycats, myself included. “Stripper Bingo” proves just how visionary she really was, pioneering a style way back in 1999 that so many of us are still trying to emulate today.

Seth Stevenson, contributor

About a month after I came to Slate, in July 1997, our copy editor Lakshmi Gopalkrishnan filed this five-part diary while visiting her family in Kerala, India. The writing is sharp and delectable, opening with the line, “Beef blood, I discovered this morning, doesn’t dissolve in the rain.” But I remember that what struck me even more than the quality of the series was the ethos it signaled: Everyone at Slate—from copy editor to photo editor to intern—was encouraged to turn their ideas into writing for the site. It’s an egalitarian, open-minded stance that was fostered by Michael Kinsley and has been a part of Slate culture ever since. All sorts of great work has resulted, coming from all sorts of talented colleagues. (A recent favorite: designer Derreck Johnson’s spirited 2014 defense of his AOL account.)

June Thomas, culture critic and editor

I’ve written or edited thousands of pieces in my years at Slate, and I have to admit that the piece that has stuck with me most surprises me. As the editor of Slate’s travel section, I worked with many wacky, wonderful, funny, fearless writers. Elisabeth Eaves was one of my favorites, because whether her subject matter was adventure sports in New Zealand, diving in the Caribbean, or touring Eastern Europe on a motorcycle—activities I would never, ever contemplate—she always managed to make me understand how it felt to do those crazy things. When she went to Seville, Spain, to learn to dance flamenco, the second entry of the weeklong series, about what it means to become so consumed with art that it takes over your life, immediately took up residence in my brain. Elisabeth notes that her own childhood obsession, ballet, taught her self-discipline and made her a perfectionist. She goes on: “It also taught me a lesson I think is crucial. Some kids get it from music and others get it from sports, but a lot never seem to get it at all: Being very, very good at something is very, very hard. The upside of knowing you may never have the talent to pull something off is that if you do pull it off, you know it’s no illusion. You have a realistic picture of where you stand, with all the pain and pleasure that involves.” Don’t we all want to know where we stand?

Josh Voorhees, senior writer

On the eve of the 2013 government shutdown, Joshua Keating imagined how that debacle would have looked if viewed through the tropes and tone normally employed by the U.S. media to describe events abroad. The result—the first installment in what remains one of my favorite reoccurring features on Slate, or anywhere else—was somehow both laugh-out-loud hilarious and sit-in-silence depressing, and lines like this one echo in my head as the end of each new fiscal year brings with it the rumblings of another shutdown every fall: “The capital’s rival clans find themselves at an impasse, unable to agree on a measure that will allow the American state to carry out its most basic functions.”

Forrest Wickman, senior editor

I nominate “Can Peeing on Your Hands Make Them Tough?” not just because it was the first Slate piece ever written by my boss, although we should never, ever forget that it was. No, I nominate this important piece of investigative journalism because it embodies Slate’s fearlessness in following its curiosity wherever it leads, even when a question might seem too minor or dumb to justify hours of reporting.

This spirit was embodied for years by Slate’s Explainer column, which would stop at nothing to get to the bottom of questions like “How Complicated Was the Byzantine Empire?”, “Did Hitler Invent the Hitler Moustache?”, and “Why Does God Love Beards?” (My own first Explainers, in the interest of fairness to Dan: “How Gross Is That Water That Drips From Air Conditioners?”, “Why Does Semen Glow in the Dark?”, and “If You Go to School on the Equator, When Does Your Summer Vacation End?”) Today it lives on in the form of the Slate Investigation, which gets to the bottom of such timeless questions as “Why Do TV Characters All Own the Same Weird Old Blanket?”, “Why Don’t Hotels Give You Toothpaste?”, and “Is Hamlet Fat?”

There have been many attempts over the last 20 years to define Slate-iness, but to me these articles epitomize a crucial element: serious journalism that does not take itself too seriously. (Note: Dan did not actually pee on his hands while reporting his article, as far as I know.)