We’re posting transcripts of David Plotz’s Working podcast for Slate Plus members. This is the transcript for Episode 6, which features Tom Toles, an editorial cartoonist for the Washington Post. To learn more about Working, click here.

You may note some differences between this transcript and the podcast. Additional edits were made to the podcast after we completed this transcript.

David Plotz: What’s your name? What do you do?

Tom Toles: Hi, I’m Tom Toles. I’m the editorial cartoonist at the Washington Post.

Plotz: What are you required to produce each week?

Toles: Actually, I’m required to produce five original editorial cartoons each week, but I do six. And why do I do six? Well, because I came to the Washington Post and they said, “We’d like you to do five.” I thought, “Well, I’m at the Washington Post, I should do six.” So, that’s why I’m doing six. I do one Monday, one Tuesday, one Wednesday, on Thursday, and two on Friday. And I cover all the days except Saturday, where they run a drawing board of other cartoonists’ work.

Plotz: So, today is Monday. You come into work. What time do you get in and what do you do first thing?

Toles: OK, this is another difference between me and almost every other cartoonist I’ve talked to, including my predecessor, Herblock, who was notorious for coming in late and staying all hours. All the cartoonists—or virtually all of them I talked to—tend to run that way. Slow to get into the office, taking their time, thinking about it. Deadlines are made to be pushed. And I’m sort of the inverse of that. I get up at around 5 in the morning. I’m in the office at 6 in the morning, and—

Plotz: You’re in the office at the Washington Post at 6 in the morning? Is there anybody else here?

Toles: Let’s just say, it would be a poor venue to attempt a mass shooting episode here, because it’s pretty empty, yes. But yeah, it’s nice for me for a variety of reasons. One, I like peace and quiet, but that’s not the main reason though. They say there are morning people and evening people, but actually there are really only two kinds of people, there are evening people and me. The number of people that are genuine morning people are so rare that I sometimes feel almost unique in that way.

But anyway, I wake up pretty much in terror. I’ve found that terror—creative terror—is a pretty substantially effective motivator. The sooner I get started, I figure, the more likely it is I’ll be able to make the deadline. Although the funny thing there is, I have such a terror of deadlines that I don’t even know when mine is. I think it’s maybe 11 at night or something like that, but I’ve never gone past 3 in the afternoon. So I actually do not know when my deadline is. I’ve never come anywhere close to hitting it.

Plotz: So, at 6 you’re here. What are you doing?

Toles: I get in—let’s just say, every day at 6 on the dot—it’s not quite that, but I tend to be pretty darn regimented.

I will read as much as I can as fast as I can between 6 and 7:30. At 7:30 on the dot I will stop reading and start sketching. I will sketch from, like, 7:30 to 9. At 9 I write my blog, from 9 to 9:30. Between 9:30 and 10 I decide which of the sketches that I’ve done will turn into tomorrow’s cartoon. At 10 I go to the meeting, and at 11 I ink my cartoon. And then the rest of the time I go back to reading for the next day. I read somewhere, after I’d been doing this for years and years, that it’s actually a good idea or a helpful or useful idea to—if you’re trying to do creative work, to regiment every single variable that you can. And so then, the number of distractions or differences from day to day is reduced to the bare minimum, then you can really focus all of your attention and all of your energy on the creative process. So that’s how I justify why I’m doing it, but it’s actually just my proclivity.

But, anyway. So, what am I reading? I obviously start with the Washington Post. Then I read the New York Times. And then I have a list of websites and blogs that I look at. I read, you know, pretty much the same ones but I will vary it from day to day depending on what the news is looking like. If something jumps out at me as either a huge news story or an interesting news story, an important news story, or a story that gets under my skin, or I feel a strong reaction to, or feel that I need to make a comment about, I make a running list of possible subject areas. So I’ve set myself up for a limited number of areas to focus on when I start sketching.

And then I will do four sketches every day, because it has to be the exact same number every day if you’re a regimented person. So every day I do four sketches, and I work, and if I’ve got three and there’s just nothing left I

Plotz: When you sit down to sketch, where do you do it and what are your tools?

Toles: OK, well, I have a drawing board here—we’re in my office right now at the Washington Post—I have a drawing board, an angled drawing board the way you’d think of a drawing board as looking. I—

Plotz: Can I just interrupt you? Which is, like, I like that you live the cliché. It’s like, it really is—it looks like the office that the cartoonist would have.

Toles: Yes, and it is. It’s actually not my office, though. It’s Herblock’s office. It will always be Herblock’s office, I am just the current resident. But anyway, it looks like a drawing board, and it’s like, every day it’s—speaking of living the cliché, it’s like, “Well, back to the drawing board.” It’s like, over and over, I’m always coming back to the same place and the same blank sheet of paper.

The sketching I do on newsprint, which is the insider term for the type of yellows-ish cheap paper that they print newspapers on still in some quantities, and it’s—I use that because quantities of it float around in newspaper buildings. It’s hard and harder to find it, but anyway, that’s what all my predecessors always used and that’s how I got started. Actually, I use nothing but a pencil, but there’s a special kind of—another old newspaper item, an ebony pencil. It’s a very dark, soft pencil lead. It’s great on newsprint because it makes—you can make a light line and a dark line, but even if you make quite a dark line you can eradicate it fairly successfully with an eraser, because the process of sketching is often trial and error, and trying different things, and moving things around. So, it’s very simple, very low tech, and very inexpensive, but really does the job and it also actually scans well. Now when I finish the sketches, I used to take the pile around and show—that’s another cartoonist tradition, of showing people you work with the sketches you’ve done that day and getting some—or, an initial reaction. Now, I do it. I scan them all and send them by email, and can get my reactions that way. It’s simpler, but that technology actually scans up quite nicely also.

Plotz: Are you required to show your cartoon to anybody? Does anyone else have veto power over your cartoon?

Toles: That’s an interesting question, and that varies, again, from cartoonist to cartoonist. I do, of course, show my cartoons to my editor, Fred Hiatt, and we have a similar relationship to the one I had previously in Buffalo and the one he also worked with Herblock with. In other words, I will show him my cartoons. I am very interested in what he thinks about it. Virtually every subject I’m drawing on he knows more than I do, and he’s also got a pretty good eye for what works as a cartoon. So, he’s very high on my list of who I’m listening to closely, as to his preferences.

But the way the agreement works is that I will draw and finish the cartoon that I select, that I think is the strongest one, and that accurately reflects my strongly-held views on whatever the subject is. And Fred has ultimate veto power in that he can choose not to run it, but the way it works is, he can’t ask me to either make changes that I don’t want to make or to do a substitute cartoon. And the process has worked very smoothly. He’s never rejected a cartoon that I have submitted and said, “This is the one I want to do.”

Plotz: That’s extraordinary.

Toles: It’s extraordinary in the sense that an editor is not rejecting a submission from someone who’s doing work for you, but it’s not extraordinary if the understanding going in that the cartoonist—both the editor and the cartoonist want the cartoonist to be presenting unfiltered, unvarnished, unmediated, real personal viewpoints. That’s of value. And believe me, I’ve worked under different systems, and when the cartoonist doesn’t have that freedom the nature and content of the work starts changing and getting skewed. And even if you don’t know that or can document that, or a reader couldn’t possibly know, I just think it feels different. I think readers can sense over a time span, is this really a person? Is really a person, a specific individual’s world view, point of view, passions and interests? Or is it more a committee product?

Plotz: If he violently disagrees with the point of view you’re taking in the cartoon, does he say, “I think you’re full of it, Tom, but go ahead?”

Toles: I have invited him to speak to me that way—maybe not quite that language—I certainly am interested in when—especially when he thinks that the fact base or the interpretation base or the analysis base is just off-point, getting something substantially wrong. I would want to know that. But I think his opinion is that he’s better off and I’m better off if he doesn’t start monkeying with my head that way, and so he—even though I’ve asked for that kind of feedback—gives me very little of it. He will tell me which cartoon he likes better than others, and over the course of days and months and years I have developed a pretty clear sense of what his types of preferences are.

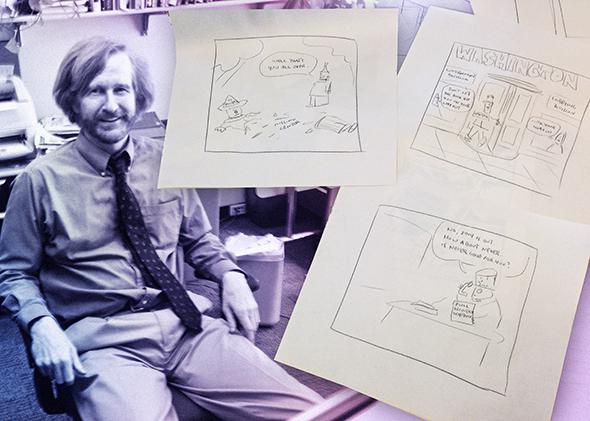

Plotz: Let’s move back to the sketches. So, today is a particular day. It’s Monday. Can you actually go to your sketches and get them? Here we have four sketches. They’re all the same shape. They’re all in a rectangular box. Do you just hand draw that, or do you have a ruler that does that?

Toles: If you look at them carefully, yes, they’re hand drawn. I just need to roughly get the topography of what the cartoon space is going to be.

Plotz: So, tell us about each of the three rejected ones, if you don’t mind, and then the one you ended up using.

Toles: OK, well, I’ll start in the order I worked on them in. I knew that I was going to have to try something on Iraq, because the story is so big and chaotic and awful right now, that I was going to have to do something on that, although that’s a very difficult type of thing to do a cartoon on. But I started with a note that I had made on Friday, that while we don’t know that Eric Cantor will be joining a lobbying firm, I thought, jeepers, let’s just say it’s a likelihood.

So, I started with something with Eric Cantor and a revolving door. I don’t know how much of the detail you want to get into, but anyway, I’m not sure this is ready to run yet because it’s making a very specific prediction or implied prediction, and, you know, while this is a likely scenario to play out, I don’t know. Every once in a while you’re surprised. He might turn out to be a university president somewhere. But anyway, so, this one might—even if I decide that I need to do this cartoon sometime, it might just have to wait until I have a better sense that it matches with the facts as they actually are developing.

Then there’s, the economy is a constant thing. This is, like, a—it’s the—the separating, the polarizing of the economy itself into—actually, this isn’t the economy at all. It’s the US political system. There was a big study last week that America is polarizing even more than it has been. It’s great to be able to use cultural references, but the shared pool of cultural references now, my rule is that we’re down to the movie The Wizard of Oz, is the only thing that everyone still is familiar with. So I did something, the scene of the scarecrow ripped apart where his head is over in one place and his legs are over in another. And this was a rare instance where, in this sketch I’m referencing another very famous New York cartoon by Bob Mankoff, which I think is almost now as well-known as The Wizard of Oz. It’s the cartoon where a guy is on the phone saying, “No, Thursday out, how about never? Is never good for you?” The endlessly non-arriving robust economic recovery just reminded me of that, and so I’ve got Uncle Sam holding a full recovery schedule and saying, “No, 2014 is out. How about never? Is never good for you?” Which is how the recovery is starting to look to me.

Plotz: Can I stop you? So, you have an Uncle Sam in this and you had a Wizard of Oz in the other. What are the archetypes that you have to keep coming back to? And then, are there ones that are you just like, “Oh, God, do I have to do another Uncle Sam?”

Toles: Yeah, I mean, I do that every day I do Uncle Sam, which is way, way too many days. Uncle Sam, there’s one. The Republican elephant and the Democratic donkey. I’m going to those all the time and I hate it. I think it’s a weak, lazy way to go. I think in a way it just undercuts all the things I would love to be doing. And there are cartoonists who have probably higher standards and principles than I do, who won’t go there. They will find a way to have just ordinary people talking or the politicians involved representing themselves, and, you know, come at it without the standard cliché figures.

I’m of two minds on that. One, what I just said. I think it’s a bad way to go on principle. On the other side, the window for attention in readers now, online in particular, I think is getting shorter and shorter. And I used to do very elaborate cartoons, multi-paneled, six panels, eight panels, twelve panels, where I would get into a lot of esoteric dialogue, discussion, and very intricate little ways of approaching things sideways. I just—I always ask myself, how much time can I legitimately ask for, for the size of the point that I’m making, in the environment that we’re working in now? I mean, I find myself recently thinking I’ve got to do—I mean, traditionally cartoonists—editorial cartoonists—have said you’ve got, like, three seconds, five seconds, and you’ve got to catch them quickly. Bing, in, out, or forget it. Well, I didn’t start my career that way at all, quite the opposite. I thought, you know, people are just sick of that. I want to do something different.

My ideas on these subjects are a little more elaborate than that, and I’m just going to follow what I think my strengths are and try to portray my point of view as it is. And that hasn’t changed, like, fundamentally, but functionally it has changed in that now I’m working faster again, on a simpler concept, a simpler delivery, just because right now that’s a better match to what I think I’m trying to deliver in the medium that I’m working in.

Plotz: OK, let’s talk about the final one, the one that you ended up choosing.

Toles: OK, well, Iraq. I mean, it’s just a disaster, I mean, in every possible way. And, you know, what do you do? It’s not a subject that you can be funny about. It’s complex and resistant to virtually any policy option. So, what do you do?

Well, there’s a number of ways you can go. I mean, what I was working with today, when I’m stuck and thinking about things I try to step back and say, OK, I’m going to try to ignore what everybody else is saying about it, some of the particulars of the events that I’m not going to be to solve. And you know, I ask myself, what is it that I think that maybe is not what’s everybody is talking about?

And for me, my understanding of Iraq just—it depends on when you start the clock. I like to go back to the pivot points in American policy involvement in Iraq, and the question that I keep coming back to is—you look at the makeup of that country and you say, “Well, all right. Our goal here is to make a functioning modern democracy.” And my question has always been, with the religious and ethnic divisions in that country, tell me how that works. And so I went back to that, and I also went back to or referenced one of the original justifications for going into Iraq, the weapons of mass destruction and whether they were there. The cartoon that I did is a kind of combination of those, that they found the weapon of mass destruction but it’s not chemical, it’s religious intolerance. I mean, I could have thrown in “ethnic” also with the Kurdish part, but I simplified it down to religious intolerance. It doesn’t, like, solve Iraq. It doesn’t tell us what we should do now, but it’s just a way to, you know, if you’re reading only about the particular atrocities and looking at the map of where troops are, and how many people are left in the US embassy, everything is very short-focused.

This is not the 30,000-feet view of it, but it’s sort of a mid-range, just a way—another way to think about what’s going on, that’s just helpful in that, I think it distills a portion of the subject and gives readers a little bit of a different approach, a way to think about it.

And then at the bottom I said, it was in plain sight all along, which to me it was pretty plain, but we spent a lot of time and discussion in this country kind of trying to talk around that problem and it keeps coming back. And that’s the thrust of what I was trying to do in this cartoon.

Plotz: Does the line, “I think we’ve located Iraq’s weapon of mass destruction,” and then there’s the barrel of religious intolerance, a steaming barrel of religious intolerance—but did that line come to you as you were reading? Does it come to you from thought? Does it come to you from—where do you think it came from?

Toles: OK, I knew we were going to get to this. The only way I can answer that question is, I don’t know that I’ve ever called it this before but I’ll call it this now, is the “Evel Knievel” explanation of political cartooning. I can spend that hour and a half reading, and it’s very mechanical and explainable, and I can tell you how—once the sketch is done—how I transform that into an inked, finished product. I can even tell you something about, like, on the Iraq barrel thing, if you look at the sketch and you look at the finished, they’re flipped. The barrel is on one side in the sketch and it’s on the other side. I explain to you why I arranged things and why I do things, specific things. But the exact little—there’s a gap that the “Evel Knievel” has to go across on his jet-powered motorcycle, and that part’s just a little bit hard to explain. You can manage the ramp up to a political cartoon idea and you can manage and explain the catching ramp and the finished product, but there’s a mental thing—there’s a zone of uncertainty that happens in the middle that’s just a little bit hard to—well, I don’t understand it myself. Connections get made that aren’t standard connections.

Plotz: Have you ever tried to watch yourself constructing a cartoon? And if you do, are you unable to do it?

Toles: No, I’m very much unaware of my physical presence, location, anything while I’m working. When it’s going well, it’s a process of blocking everything out, and I don’t even—I have no awareness of my hands holding a pencil, or sitting at a desk, or anything. I’m just in the creative miasma and flow, and then, you know, there’s obviously got to be some kind of management going on. But it’s very intuitive and instinctive rather than conscious.

Plotz: Do you think if you worked—let’s say, every day three people came and sat on your couch and watched you as you were doing it—that you would be able to do your job?

Toles: Probably, but man would I hate to try. I just—I ask for very little in terms of support or extra little favors at work, but there have been a couple of things. One is, I need to have a door I can shut because I have to get into the place where there’s no distraction, where I can be just unconscious there, a conduit of ideas and creativity. Because it doesn’t take a lot to be thrown out of that place, and I have to be in that place to do the work I do. It’s possible I could train myself to just not see other people in the room, but if I was thinking about them in any way nothing would happen. The process would simply stop.

Plotz: How long did it take you to draw, do you think, the religious intolerance sketch today?

Toles: Well, I certainly have one of the simpler visual drawing styles of cartoonists. There are cartoonists that have extremely elaborate, very highly worked visual representations, and you see their stuff on walls, hung up in a gallery. And you think, “Wow, that’s just beautiful stuff.” And for me, I think about that from time to time, because I look at my originals and I think, in terms of a piece of artwork, it’s kind of like nothing. The few time I’ve done shows, I look at them on the walls and I think, “Well, they don’t look good at all on walls.” But then I go back and say, “Well, why did I draw it that way?” Because I can draw different ways, and my answer is, “Because I’m not drawing them for walls in a gallery.” And I’m not even drawing them for the history of all-time art, I’m drawing them to serve a communications purpose in a very short timeframe in a very particular media environment. I mean, it’s two environments now, both on paper and online—although interestingly enough, I think they work more similarly for cartoons than I would have guessed.

Plotz: So, this is a very serious subject here, but this is funny. How do you—why is it important to live in a world where all things can be funny, even if they are very darkly funny?

Toles: Well, if you look at the history of political cartooning that has not always been the case. There was a revolution in American political cartooning around the middle of the 1960s when Pat Oliphant came to the Denver Post from somewhere in Australia, and he brought sort of a—I mean, he brought different elements. He brought some of the European tradition, but he also consciously or unconsciously tapped into the more humorous, satirical, Mad magazine approach to life. And political cartooning was—it just changed. It was a clear, distinct change in tone. And while I never thought Pat Oliphant is the cartoonist I wanted to be, he created a world that I felt very indirectly comfortable in, in that it suited my personality. I thought it was overall a more effective tone, to introduce more humor into the work. I think humor—I mean, it’s not an original thought—but humor is a great way to engage a reader, to catch their interest, to make what you’re doing compelling to them and appealing to them on a superficial level. And then you hope also that that immediate superficial entertaining appeal gets translated and re-infused back into the point you’re trying to make, which is the main thing. Once you’ve seen the potential of humor as part of the process you just don’t want to go back, because it’s just such an effective communications device. And plus, as I said, it fit my personality. I tried to create a very individualistic style but the world of humor and political cartooning, that was the part that I wanted to incorporate.

Plotz: I suppose also, speaking of the digital age where you now live half the time, things that are funny on the Internet are more successful than things that are not funny, almost without exception.

Toles: Yeah, I mean, and it’s not all a good thing, because—there’s actually been this smallish debate within the tiny world of political cartooning, whether the humor tail started wagging the dog in a lot of political cartooning. Where you’d see something and you’d recognize the subject matter as topical subject matter, and you’d recognize that a joke was being delivered, but then you’ve done—as I said, the second look, you look and say, OK, well, what is this cartoon actually saying? And the answer is, “Well, it’s not saying anything at all.” And you can say, “Well, a certain amount of that is great. It helps build your readership. You know, you don’t have to be serious or make a heavy-duty point every single day, a little bit of lightness, a little bit of just topical lightness doesn’t hurt once in a while.” But—and that’s true—but in a lot of instances day after day you would see cartoons that had no message, no information, no anyway. They were just making a little light joke about something that—words that were in the newspaper the day before. And so, as I said, that’s a great thing to have but, you know, use it with some intelligence, please?

Plotz: With that in mind, what do you think a political cartoon can accomplish?

Toles: I mean, that’s a question I’ve asked myself every single day since I started. And even in the instances where people hold up cartoons or cartoonists—Thomas Nast, some of Herblock’s Nixon stuff—as having really achieved something. It’s a tentative case at best. I look at it this way: it’s part of a mix of discussion. For me, the vastly more important part of understanding anything is reading a well-written, well-reported story or a well-argued case about it, better in virtually every way. Cartoons are only useful and effective and helpful working off that base. Their strength and their weakness is their simplification of issues.

It gets ever hard to tell yourself you’re going to change the world with political cartooning, because the environment of a monopoly position where the newspaper in a city is read by everyone, everybody’s going to see your cartoon, it’s just going to dominate the conversation in the way that newspapers or network news did in the past—well, that’s over. Now you’re in there fighting in the scrum, a million different voices.

Cartooning actually works amazingly well in the new environment because it is quick, it is humorous, but it’s only as effective as both not just the presentation, and not just the humor, and not just the immediate appeal, but it is actually helping anybody understand anything.

And how often are you right? Maybe sometimes you just draw a cartoon that for some people it was the turning point in the way they thought about it, and that person or those people turned out to make the difference on the issue.

I tend to think of it as just, it’s my best effort to help an intelligent, engaged conversation about American and world policy that is not a chore to read but is, while humorous in affect, is serious intent, and that’s going to be worth something. And that’s why it’s worth my time to come in here and go back to the drawing board every day.