We’re posting weekly transcripts of David Plotz’s Working podcast for Slate Plus members. This is the transcript for Episode 10, which features appliance repairman John Lefever. To learn more about Working, click here.

You may note some differences between this transcript and the podcast. Additional edits were made to the podcast after we completed this transcript.

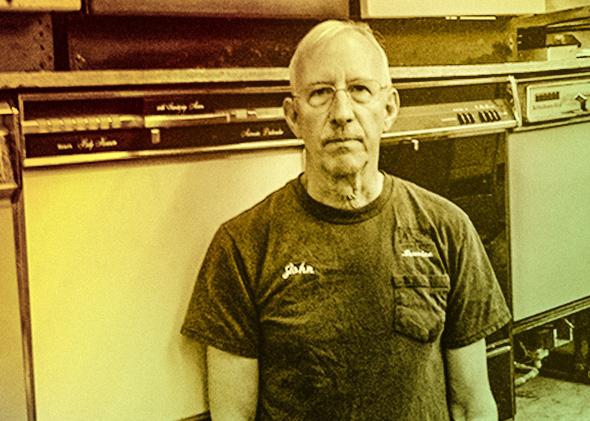

David Plotz: What is your name and what do you do?

John Lefever: My name is John Lefever. I repair appliances, major appliances in customers’ homes. Basically, in-home service. We also do some sales of appliances and consulting on appliance sales and purchases, and best use, and the most ecological of appliances.

Plotz: Tell me about a typical encounter at work. How do you get a customer? Once you get to a customer, what do you do? How do you do your work?

Lefever: Most of our customers come from either word-of-mouth or one of the consumer organizations that rates companies. Nowadays, community listservs pass your name around—but it’s mostly reputation-based. That makes our job easier right off the bat. You know, most people have a positive impression of us before we even get to their house, and then we’re willing to spend a little time with the customer, the actual technician, if needed, helping them decide whether a repair is the appropriate course of action for their ailing appliance.

So, we will talk to the customer. The typical customer is going to ask, “Should I fix it or not?” I get that question many times every day. And then I ask them questions based on if they like the product. If it was something that they always liked, I often recommend repair. And then based on our direct experience with similar machines, we try to advise them whether it makes sense to make a repair.

And so we do that beforehand in many cases, and once we get to the customer’s home, we’re doing much the same thing. We look over the product and find out what—how serious the malfunction or difficulties are. We have a discussion based on that. Many of our customers are very interested in the cost of the operation of things, and we often advise. A little bit of a side interest of mine is the ecological costs of running things, life cycles and things like that. So often my decision will be tempered by that, too, or at least I’ll give that advice if asked and sometimes even if not asked! I’ll suggest that maybe this 30-year-old refrigerator may not be a good candidate for repair because it costs four times as much to run as a new one.

Plotz: You’re effectively a physician. Tell me about an encounter with a recent patient, something you diagnosed and how you went about resolving it.

Lefever: Yesterday I looked at a Whirlpool 24-inch stack washer/dryer. It’s 18 years old. It needs a fairly major part. The frame cracked in the washer. This is a known defect with these machines eventually. The repair is going to be about $450 to $500, and so I had a discussion with the customer whether they wanted to repair it or not. The replacement of this machine would cost $1,280.

And, you know, and her initial reaction was, “Gee, at 18 years does it make sense to put even nearly $500 into this machine. And after she went over all the ins and outs of it, she initially said, “Oh, I’ll just replace it. It’s 18 years old.” But then she decided, well, No. 1, it’s a rental property for her. If she replaces it she has to write off the cost of the new machine over several years. If she does the repair it’s an immediate write-off. And so for that reason among others she decided to actually make the repair. Many people would not repair something that expense level and at that age. But it’s partly because she has confidence in knowing that we could repair this machine.

I also told her if we bring you the new machine I’m going to take your machine back, rebuild it, and sell it, because it’s excellent shape. So you have to analyze all of the data. The exact same machine in a different situation, maybe in a townhouse with a husband, wife, and a couple of kids would probably be pretty useless by this time. This machine was also in a one-bedroom apartment and had minimal use, probably only one user for most of its life.

Plotz: tell us exactly how you’ll repair it.

Lefever: The washer has a cracked frame, so I actually have to pull the washer section of the machine out. It can be done in the apartment. We put down a dropcloth, we pull it out, and we disassemble the whole thing. We have to remove the tubs, the motor from the frame, the transmission, and basically come in with the new part and start reassembling it. And taking something apart pretty seriously like that gives you a good chance to check the condition of other seals, and drive couplings, and maybe the water pump. There may be some more minor parts that are showing signs of wear, and they would be replaced at the same time so that you’re not likely to have any callbacks.

One of the wonderful things about something that’s sort of mechanical like this is, you can pretty well predict by examining it whether it’s going to fail again soon. I remember I had friends in the TV repair industry years ago, and you could do the best job and have a television or something working perfectly, but you really can’t predict when certain electrical parts are going to fail. There’s no real test or way to predict with any accuracy when they’re going to fail in the future. So, that was one of the frustrations with having electronics repaired sometimes and still is. Certain failures can be intermittent and so forth. But on something like a washing machine or something, there’s a pretty good chance if you do a good job it’s going to work great.

Plotz: How many customers do you usually have a day?

Lefever: I try to do six appointments a day. There were times in the past I actually was doing more than that, but I find just because of the geography and the way we run the business, and because I want to spend a little bit more time helping customers before we get there, six seems to work pretty well for me. And I just do it five days a week. There are times I’ve done as many as 10 a day in periods of my life, and we used to try to always do eight a day at one point in time, but we were doing a lot more warranty work at that time and a lot of the repairs were a lot simpler. When you have new appliances, it’s more often a simple adjustment, or a little part, or something. But when you’re trying to actually repair machines that have a little age on them and do have a known problem, it takes a little longer to give the customer and the machine the time it needs.

Plotz: How do you deal with the frustration that I’m sure some of your customers have? Surely you’re late sometimes or an appointment goes awry? How do you avoid that, and then when it happens, how do you handle it afterwards?

Lefever: Well, we try to accommodate as much as possible, but there are definitely times you can’t. Almost every day when we figure out schedule there’s at least one or two people that are a little disappointed, but if we can make any further adjustment we will. But beyond that, sometimes the customer will end up rescheduling if it’s impossible for their schedule, or they figure out a way to make an adjustment very often. A little bit more of the burden seem to end up on the customer, sometimes, having to figure out a time, but we do try to get down to a two-hour window for people when we’ll arrive. But are there definitely times where you have one or two calls that take a long time and you’re running late. We try to let them know. We do generally let the customer have the cell phone number of the technician if they have a last minute emergency or want to check on them, so they can call them. And that works pretty well, but probably not very often, but once or twice a year, we’ll get somebody that is just so difficult or unreasonable—we had to do that just the other month where I never even got to the customer’s home. They were placing so many demands on us and I finally just said, “I think it would be better if somebody else did this.” And so, she wasn’t too happy about it, but I just said, “It just isn’t working.” She was making it difficult for us, rescheduling over and over again at the last minute, and you know, changing her mind. So, every once in a while but not very often. We try to avoid that, obviously.

Plotz: You go into six people’s homes every day. How do you handle yourself going into all those different people’s houses? People live differently, they talk to their children differently, there are different levels of neatness. How do you handle that?

Lefever: It certainly makes the job interesting. You meet a lot of wonderful people. That’s one of the fun things I’ve often said about the job, that probably kept me doing this so long, is the just really interesting people. And you learn an awful lot about people in general, and you can often—even the problems people are having with their appliances, you can see the dysfunction in their families. I mean, we’ve had numerous customers over the years that have just unreasonable problems with their appliances, and they will, you know, you can just tell when you get there. The kids disappear, the husband disappears or whoever, they don’t want anything to do with it because it’s a dysfunctional situation with the customer. We’ve definitely had some of those.

Plotz: What do you mean, you see the dysfunction through the appliance? Can you give a specific—not a specific name, but just a specific kind of example of that?

Lefever: Oh, I had one customer in particular a few years ago. She always had funny noises from her refrigerator. It was a fairly new Whirlpool. And every time we got there it never made the noise, but that’s kind of typical for an intermittent noise, I guess. But the thing that was odd was, again, there were some teenage kids around and they always disappeared when we got there. The husband disappeared. And then finally she called us back one time and she said, “I’ve got the noise on a tape recorder but you won’t be able to hear it well over the phone—” which it is hard to diagnose over a phone, I usually find—so, she said, “I want you to come out and listen to the noise on the tape recorder.”

So, I get there, again, everybody else disappears, and we’re listening to the tape recorder—this was actually some years ago, and it was a little cassette recorder—and we’re listening to this tape recorder, and then we hear this noise—she said, “That’s me making the noise the refrigerator makes.” She had recorded herself, and the refrigerator never made the noise. But you get a lot of that. This particular customer we had had problems with a number of times, you know?

Another time she called us and said there was a spot of—it was an immaculate house, and there was a spot of wax missing from the middle of the kitchen floor, and she assumed the refrigerator caused this. It wasn’t like something ran out from under it, it would have had to have jumped out from the refrigerator. And again, you know, she just didn’t, you know, like the explanation. She said, “Well, what would cause it?” And I said, “Something probably spilled or something, you know?” She said, “Well, what would take up wax?” And I said, you know, “Maybe citrus juices, alcohol, or something.” And alcohol was the wrong thing to say, because she said there’d never been alcohol in the house. But then her husband did come and said, “Well, you know, we were gone over the weekend and we left the kids at home.” You know, the teenagers. But, yeah, it just—we get in some interesting situations. But a lot of people—and a lot of them involved refrigerators, because I guess everybody has one. A very common but sort of comical complain is they feel like it’s running all the time, and in reality of course you’re not sitting there 24 hours a day. But I’ve literally had customers who would have the thing pulled out in the middle of the kitchen, and I had one lady, again, that had a cot set up next to the refrigerator. And she would lay there and worry about it running, and she finally—you know, she said, to get some sleep periodically she would unplug it and then go to sleep, and then she would plug it back in. But we never found anything wrong with the products, you know, but we got a lot of interesting ones with refrigerators over the years.

I had one customer in Bethesda, Maryland, that complained of frost inside the plastic bags of frozen food in her freezer, and I got to the apartment and she said, “You’re the fifth person they’ve sent up here and no one’s been able to solve this.” And I explained, you know, there’s nothing wrong. I checked over the refrigerator for its vital signs and it was fine, and I explained why frost forms inside plastic bags. And she didn’t like the explanation, and she said, “Well, you’ve got to fix it.” And then I patiently explained it again, but at this point she—you know, I finally politely said, “I’ve got to go to my next visit.” And she ran ahead of me, barricaded the door, and wouldn’t let me out. And so rather than have any confrontation with her, I picked up her phone and I said, “I’ve dialed 911. Do you want to either respond to this or wait until somebody gets here?” And she went for the phone and I went out the door. But, you know, this—we had some interesting encounters with refrigerators!

Plotz: They are presumably constantly changing the devices. Electronics obviously came in during your working life. How do you keep on top of what’s happening?

Lefever: A combination of things. Unfortunately, there is some continuing provided—mainly by the manufacturers—but I don’t really think there’s enough, and that’s one of the problems in the appliance repair industry. I don’t think there’s enough training. Beyond that, I don’t think the training that is available is often as good as it could be. So a lot of it is just a matter of reading on the Internet. I get a hold of the service manuals when possible. When I do see a completely new machine on the market I’m always very curious to learn as much about it as I can.

And it’s usually not too many years—maybe even less than a year—before I can get my hands on one physically. Frigidaire recently came out with a totally new top-loading washer, which was very curious-looking to me. So I went to the Frigidaire distributor—which is close to our company—and I said, “I want one of these machines.” And it was only a matter of three months until they had a damaged one that was physically damaged come back, and I bought it from them cheaply and we brought it back, fixed it, and put it through its paces, and we took it completely apart. So some of it has to be self-motivated, and that’s where I think our strong interest in major appliances has really helped us be a more effective company, because we’re interested in it.

Plotz: How many technicians work for you?

Lefever: It’s myself currently, and I’ve got one partner and one other full-time employee. So there are three of us on the road doing repairs.

Plotz: How do you find someone who has the love and commitment and intelligence to do this?

Lefever: Most of the people I’ve just sort of run into either from other companies—Jason, the partner in the business now, I actually met through an appliance collectors’ site on the Internet. That’s how we originally were acquainted. I’d always be interested in hiring somebody else that was really dedicated to doing this. We would have room for another person at this point, probably. But I don’t want to get too big. It seems that many service organizations, whether it’s a new car dealership or the large appliance service organizations, they tend to have more problems as they get too big. It’s just a little difficult to keep track of everything. It seems pretty consistently that the smaller auto dealers and things have a higher satisfaction rate, even though the big ones have great tools and theoretically can do things well. But it doesn’t seem like it very often works out that way unless they’re extremely expensive, you know? So—

Plotz: What’s an appliance that you just hate working on or you think, “God, I can’t believe I have to deal with this again?”

Lefever: Well, one thing in any repair, I always try to do it right the first time. So I don’t like doing things over. Certain appliances just require so much disassembly to get to a certain part. Some built-in appliances, some wall ovens and things, first of all, they have to be removed in many cases to be disassembled, and that can be quite a task to do that. A lot of the foreign products, ironically, are not very well-suited for repair. Some of the German appliances for example, they’re really not designed to be repaired.

Recently, I was repairing a KitchenAid electric wall oven and there were several young Japanese exchange students there, two women and a guy. And they were so intrigued to see me, and they were taking pictures constantly while I was doing this. They said they had never seen anybody repair something in their country. And, you know, and they just said, “Nobody would repair an oven, they would just get a new one in Japan.” And they just—and yet this was a nearly $3,000 oven, and to me it seemed crazy not to repair it. And when we were all done replacing this cooling fan in the back of it, the repair cost was maybe $320 and they were amazed at that, too. But it was kind of interesting. And I also get a lot of people that are here from other countries, too. We have a lot of international customers in the city, and they are often amazed when they find out that this washing machine or something is 20 or 25 years old and it’s still working. They seem to think that’s unheard of in other places. Despite the reputation we have in the US of being a “throwaway culture,” I think we actually repair—we’re more practical than we think, sometimes. I think most people generally have thought of trying to repair things if they can, if they know who to call or what to do about it.

Plotz: Again, I don’t expect a dollar amount, but do you make a good living doing it?

Lefever: It’s been a good living for me. My two older brothers, for example, one’s a very good architect and the other is a quality control engineer, because of the amount of time they spent in school—and they both had job changes throughout their careers, they are both a little older than I am, they are like, 68 and 66 right now—I think financially I’ve done as well as they have, because I started working a little earlier and so forth. We’ve never had so much as a bad week, let alone a bad month, in 35 years. The business is very consistent, and so that is reassuring. I didn’t have the stress of changing jobs. My next older brother lost three jobs when companies just merged or closed down, through really no fault of his own. And my oldest brother in the architecture industry, again, his firm just completely closed that he was working for, and he had to find another job.

Plotz: Even in the height of the recession you still had plenty of work?

Lefever: Yes, in fact, it can be argued—and we can certainly demonstrate—that the recessions are almost good for us. People are going to be a little more apt to fix things and they spend a lot more money fixing them, even sometimes more than might be reasonable. But people have gotten so used to having things like refrigerators and dishwashers that they’re going to do it one way or another unless they’re really down and out. I noticed that during the first Reagan-inspired recession in the early ’80s. People all of a sudden were spending $300 to fix a dishwasher in some cases—over half of what a new one would have cost at this time. But people wanted to have one and they didn’t want to go out and spend any more than they had to to get the job done. And so, we definitely do well.

And when the times are good, too, it helps. People are more apt to spend money on things that aren’t maybe so essential. They’ll buy icemakers or new appliances that maybe aren’t so essential.

Plotz: That’s so interesting. So, no one will ever go without a fridge. If you fridge breaks down, no middle class American—even non-middle class American—will go without a fridge.

Lefever: Very, very few would, yes. I have seen it, where people decided they could live out of a cooler and maybe did it for six months or a year—or they lived out of the refrigerator in their neighbor’s apartment or something. But I haven’t seen many cases. Certainly people do live without dishwashers and washers and dryers, but even living without a washer and dryer in the Washington metro area is tough. There aren’t many laundromats anymore, and people with the busy life that we all lead nowadays, they don’t want to take the time to take their laundry to a laundromat. They’re doing it in between doing other operations or other activities around the house. They don’t want to take the time to do it.

Plotz: You have, I believe—based on my own experience—a very good reputation. Your firm has a very good reputation, and you appear to have good business. Why don’t you just constantly raise prices? Do you seek to maximize your income, I guess is the question?

Lefever: That’s an interesting question that some of our friends and all we’ve talked about over the years. And based on reputation and things, a number of my friends say, “Well, you guys could easily double your rates and you’d probably make more money and not work as hard.” And I think we could.

I think if we did something like that, we would also lose a lot of our customers. A lot of our customers do call us for good value on repairs. Everybody’s always looking to get the best for the money. So, we probably couldn’t charge a lot more. One of the two different motives I’ve always sort of operated by—I’ve always felt that you should be able to do a little bit better job for a little less than most of the competition, than the average one. And then my father spent his whole life in the consumer and co-op movements, and it was very heavily steeped in us, you know, to be honest and to provide a good service for the money. I think it’s worked well for us. I think we could charge a lot more, but I think—I know a lot of my competition does—but you know, earlier this year most of the other appliance repair people in the area were actually pretty slow. I would go to a parts distributor or something and they were complaining, “Gee, there’s no business, we’re really slow.” And I hated to admit when they asked me, “Are you guys busy?” And I said, “Yeah, we’re still booked up days in advance.” The ecological side of it influences me, too. I like to be able to save as many products that should be saved, so that motivates me, too. I don’t want to just go out and condemn things.