This is a transcript of the July 13 episode of Whistlestop, a podcast about presidential campaign history hosted by John Dickerson. Transcripts are provided to members lightly edited and may contain errors. For the definitive record, consult the podcast.

John Dickerson: Our Whistlestop today is November 3, 1968.

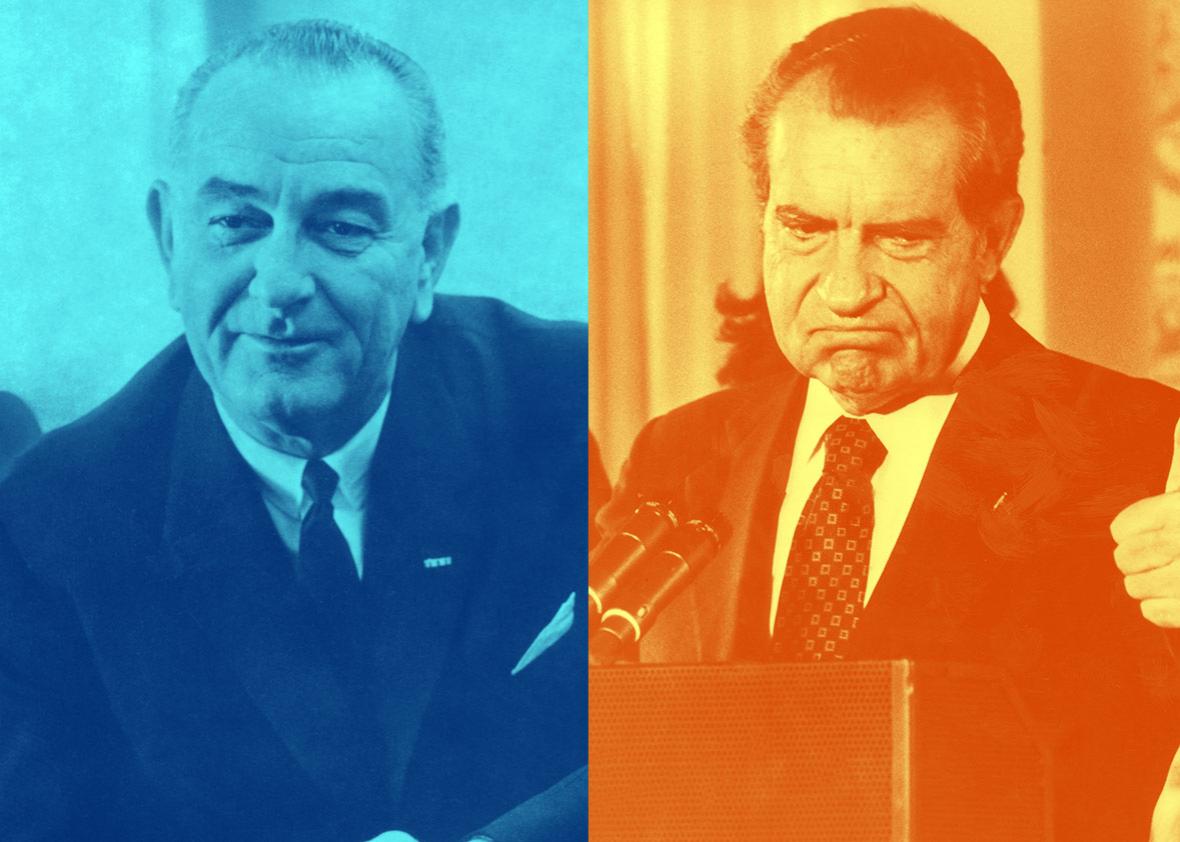

President Lyndon Johnson had been trying to negotiate a bombing halt in Vietnam. More than 11,000 Americans had died the year before, and close to 17,000 had died to that point in 1968—the most in any single year of that conflict.

Johnson had been patiently working to halt the bombing for months. Hanoi in the North had demanded an unconditional halt to the bombing on North Vietnam before it would discuss any settlement of the war. Johnson, however, insisted that Hanoi meet certain secret conditions before he would call off the aerial and naval bombardments: The North wouldn’t bomb the cities or move into the demilitarized zone. In the fall of 1968, Hanoi had finally accepted his demands, but just as he was working on the U.S. allies to put this pause into place—most important, just as he was working on the South Vietnamese, America’s ally—the president and his plans were unwound.

There were two culprits. The first was from his own team. Candidate Hubert Humphrey, the vice president who was running since Johnson had taken himself out of the race, gave a speech saying he would withdraw troops if he was president. “Get out of the Vietnam War.” McGeorge Bundy, a former national security adviser to Kennedy and Johnson, offered a similar statement. The suggestion was that if Humphrey won, he would leave the South Vietnamese without an ally and they’d get nothing after years of fighting.

The other problem came from the other side, the Republicans. Richard Nixon, he was telling the South Vietnamese that if they did not accept Johnson’s bombing pause in advance of any peace talks, that would give them a better deal in a Nixon presidency. Now, how was he making that link? Well, the South Vietnamese believed that if there was a bombing pause—the pause that Johnson had been working on so assiduously—it would help Hubert Humphrey in the campaign against Nixon. There’s a pause, Humphrey wins, they don’t get such a good deal. If there was no pause, if there were no talks, if the South Vietnamese just kind of dragged their feet, then maybe Nixon would win, and they’d get a better deal.

State of the play was that the Communists wanted a share of power in the South, and the doves in the United States thought that was maybe OK—that was the signal Humphrey was sending. President Thiệu of South Vietnam was not going to go along with that, and if Nixon won, he wouldn’t have to.

Why have we started our tale on the 3rd of November, just three days from the election? That’s when the president is on the phone with his old friend and adversary, Everett Dirksen, the Senate minority leader. The president’s calling from the LBJ ranch. It’s 9:18 in the evening, and he’s explaining to Dirksen what the stakes are for political opponents to delay this peace deal for the purposes of taking political advantage. (The following recording, and a lot of the work we’re going to do in this Whistlestop, is the result of the amazing work they do at the Miller Center at the University of Virginia, where they’ve transcribed and put together recordings from the Johnson era. Also, I should note a great book on this question is called Chasing Shadows: The Nixon Tapes, the Chennault Affair, and the Origins of Watergate by Ken Hughes, who is a part of that Miller Center.)

In this tape, Johnson refers to “the old China lobby,” meaning Chinese Americans who opposed the Communists in China and supported the nationalist regime of Chiang Kai-shek. Anyway, here’s the conversation with Dirksen on the 3rd.

Lyndon Johnson: Now, since that agreement we have had problems develop. First, there’s been speeches that we ought to withdraw troops.

Everett Dirksen: Yeah.

Johnson: That was Humphrey and Bundy.

Dirksen: Yeah.

Johnson: Or that we stop bombing without any … obtaining anything in return.

Dirksen: Yeah.

Johnson: Or some of our folks, including some of the old China lobby, are going to the Vietnamese embassy and saying, “Please notify the president that if he’ll hold out to November the 2nd they could get a better deal.” Now, I’m reading their hand, Everett—I don’t want to get this in the campaign.

Dirksen: That’s right.

Johnson: They ought not to be doing this. This is treason.

Dirksen: I know.

Dickerson: Treason. So begins our tale of the one of the great October surprises in history, depending on who you believe.

In his memoir, Clark Clifford, former secretary of defense under Johnson, described this collusion between an agent working for Richard Nixon and the South Vietnamese government. He described it as a plot to help Nixon win the election by a flagrant interference in the peace negotiations. Clifford put it rather cinematically: “History is filled with characters who emerge for a moment, play a critical, sometimes even decisive role in a historic event, and then recede again into their normal lives. Such was the function of two people who played key roles in electing Richard Nixon in 1968. Bùi Diễm, the South Vietnamese ambassador in Washington, and Anna Chennault.”

Who was Anna Chennault? She’s our main character. She was the widow of General Claire Chennault, the commander of the famed Flying Tigers in Burma and China during World War II. The Flying Tigers, you know them. The shark-face nose art planes that flew during the Second World War—part of the Chinese Air Force, actually. They were composed of Army, Navy, and Marine Corps pilots, and because the war hadn’t started yet, they were flying as Chinese against the Japanese. I barely understand the strategy involved in aerial combat, but apparently, the commander, Chennault, was so talented at using America’s limited airplanes in making high-altitude slashing attacks on the more maneuverable Japanese planes. Anyway, Anna was the widow of the commander and also the chairwoman of the Republican Women for Nixon in 1968. She was variously called the Dragon Lady and Little Flower by those in the Johnson administration. She was a member of that China lobby, strongly anti-Communist and in favor of beating back the North Vietnamese, so Nixon was her man.

In early 1968, she started as a go-between, between the Nixon campaign and the South Vietnamese government. Her main interlocutor was the South Vietnamese ambassador, Diễm, who had connections throughout Washington. In the Nixon campaign, her contact was John Mitchell. Here’s one communiqué between Mitchell and Chennault: “I’m speaking on behalf of Mr. Nixon,” Mitchell told her. “It’s very important that our Vietnamese friends understand our Republican position, and I hope you have made that clear to them.”

The reason a quote like that is important is that for a period of time in history there was some confusion about whether the story you’re hearing today was true. We’ve subsequently found notes and recordings and so forth that give it support, but at first, Nixon basically denied that any of this had happened. So did Chennault, and so did the South Vietnamese ambassador to the United States.

Chennault also passed information through the South Vietnamese ambassador to Taiwan, who happened to be the South Vietnamese president’s brother. The arrangement started at a meeting, which took place early in 1968 in New York. The Johnson administration knew about the South Vietnamese ambassador and Chennault meeting with Nixon, but they thought it was OK because, hey, the candidate running for office should be able to meet with the ambassador of an ally.

Chennault was dating a fellow named Tommy “the Cork” Corcoran, who was a Democrat, a former FDR aide and a longtime Washington … well, lobbyist—a fixer. When Johnson came to town, FDR handed him a slip of paper and said, “Here’s a phone number. When you get to Washington, ask for Tom.” A powerful, powerful person. Among the things he was known for was helping United Fruit find a way to overthrow the government of Guatemala.

Anyway, there was no reason to think, even though she was a Nixon supporter, that she would stray too far, given that she was dating Tommy “the Cork” Corcoran. What the Johnson team didn’t know, though, is that this meeting was the beginning of a permanent channel—Chennault talking to Mitchell and the Nixon campaign; then talking to the South Vietnamese ambassador, Diễm; and then Diễm talking to the South Vietnamese government back in Saigon. Chennault said she talked with Mitchell at least once a day, and Diễm, for his part, was friends with lots and lots of Washington politicians.

Now, we should put Nixon’s mindset into play here. Why would Nixon even flirt with getting involved in backchannel discussions about a possible U.S. bombing halt? Well, according to John Farrell in his new book on Nixon, after 1960 and Nixon’s loss to Kennedy, he became overwhelmingly paranoid about what an opponent would do to win an election. That was his frame of mind. He thought President Johnson would do whatever was necessary to elect Humphrey—even stage a fake bombing halt to help Humphrey’s chances.

Again, the idea being that if there was a bombing halt, Humphrey would be able to say, “Hey, see, we’re on our way out of this horrible war,” and that would give him an electoral boost. “I knew what was coming,” said Nixon, according to Farrell’s book. Big events like a breakthrough in Southeast Asia could “change people,” Nixon feared—they “could cut down a lead as big as ours.” Nixon used Chennault to let the South Vietnamese president know that Saigon would be better off if a deal was worked out in the future with a Republican president, namely, Dick Nixon. Of course, the North Vietnamese thought Humphrey would be a good person to win, because they believed that Humphrey was going to try and get out of the war right away, and that would mean they would get more of what they wanted.

On October 16th, President Johnson held a conference call with all three candidates—Nixon, Wallace, and Humphrey—to tell them about the state of these negotiations. Johnson said “there had in fact been some movement by Hanoi” but that “anything might jeopardize it.” What he didn’t tell them was that the South Vietnamese leader had agreed the day before to a pause in hostilities. Johnson saw Nixon later that night at the Alfred E. Smith Dinner in New York and told him, “Be careful about what I had to say on Vietnam.” Can you imagine that today, by the way? I mean, so what was Johnson worried about? He was worried that this delicate bombing pause would be undone by the political behavior of any of the three candidates. That’s why he briefed them on the call. The nominee of the opposition party, he was giving this information to—information that could’ve undone Johnson, because Nixon could’ve talked about it (and, in fact, that’s what Johnson alleges he did).

Johnson was willing to give Nixon this information in the middle of a campaign because he assumed that Nixon would not misuse it, that there was a certain kind of code, norms that would kick in and be in place. The secretary of defense, Clark Clifford, explains that they learned through regular intelligence, not wiretaps or anything, that Chennault was involved in this scheme, which put the administration in a pickle in mid-October after Johnson had had this conversation with the candidates—not unlike the Obama administration’s pickle when it found out through intercepts that Michael Flynn was talking to the Russian ambassador. The Johnson administration knew things about what Chennault was up to—things they shouldn’t have known because that meant they were spying on an ally. Of course, in the Obama case they were not spying on an ally. They were spying on an adversary. Here’s Johnson explaining this worry once he finds out this plot has started to take place. This is how he explains his worry about going public to his top advisers in a phone call.

Johnson: Now, I don’t want to have information that ought to be public and not make it so. On the other hand, we have a lot of … I don’t know how much we can do there, and I know we’ll be charged with trying to interfere with the election and I think this is something that’s going to require the best judgments that we have.

Dickerson: Here’s another recording from about that same time. Johnson, having learned about Chennault and about what Nixon was up to, calls his friend Richard Russell, because Russell is—even though they fought with each other over the civil rights legislation—his closest adviser in the Senate in terms of Vietnam. Johnson starts by explaining what he’s learned and how he’s learned it and why he’s turning to Russell for counsel. Basically, he says, “Well, I got one this morning that’s pretty rough for you.” Meaning, I’ve got a problem here that I need you to solve. “We have found that our friend, the Republican nominee, our California friend, has been playing on the outskirts with our enemies and our friends both, our allies and the others. He’s been doing it through rather subterranean sources here.” Johnson then lays out how he moved from having been informed by normal sources, not through wiretaps or anything, to taking more extraordinary efforts to put on surveillance to follow up on what they learned from various other sources, some of which were on Wall Street. Anyway, here’s Johnson explaining the next step he took after he heard rumors about what Chennault might have been up to.

Johnson: When we got that, pure by accident, as a result of some of our Wall Street connections, that caused me to look a little deeper.

Richard Russell: I guess so.

Johnson: I have means of doing that, as you may well imagine.

Russell: Yes.

Johnson: Mrs. Chennault is contacting their ambassador from time to time. Seems to be kind of the go-between, the Chiang Kai-Shek deal. In addition, their ambassador is saying to them that “Johnson is desperate and is just moving heaven and earth to elect Humphrey, so don’t you get sucked in on that.” He is kind of, these folks’ agent here, this little South Vietnamese ambassador. Now, this is not guesswork.

Dickerson: The president is saying, “This is not guesswork,” because the NSA has intercepted cables from the South Vietnamese embassy to Saigon, and the CIA has bugged the South Vietnamese president, so they’ve got the communication on both ends. Now we return to the conversation with Russell. The president comes back to this discussion of the woman at the center of our story.

Johnson: Mrs. Chennault, you know, of the Flying Tigers.

Russell: I know Mrs. Chennault.

Johnson: She’s young and attractive. I mean, she’s a pretty good-looking girl.

Russell: Certainly is.

Johnson: She’s around town and she is warning them to not get pulled in on this Johnson move. Then he, in turn, is warning his government. Then we, in turn, know pretty well what he’s saying out there. He is saying that, well, he’s got to play it for time and get it by the next few days.

Dickerson: It is a little later in this conversation that Johnson lets on his true motivation. He’s worried about the peace deal, because he thinks he’s close and doesn’t want to lose credit to Nixon, who he thinks is going to win the election. Here he is talking about Nixon. The reference to Eisenhower is about how Eisenhower declared the armistice in March of 1953, not long after his 1952 election. That’s what Johnson doesn’t want to have happen in his case with a Nixon victory.

Johnson: Now, I have played no politics with him. I’m not going to, and I’ve given Humphrey more hell in the joint meetings than I have Nixon. Nixon’s been pretty responsible. But I don’t want to pass up an opportunity and just sit here on my fanny till he comes in and let him just pick up like Eisenhower did the Korean thing, and say, “Well, I did so and so.”

Dickerson: Johnson’s talked to his ally Russell and given him the rundown of what’s happening—what they’ve heard from their sources on Wall Street who are connected with Nixon, what Nixon’s forces may be up to—and also, he’s hinted, or made very plain, that he’s got some wiretaps going on. What do the wiretaps from the Federal Bureau of Investigation reveal? The wiretaps were of the South Vietnamese embassy and they struck pay dirt when they heard Chennault on the phone with the South Vietnamese ambassador saying that she had contacted her “boss,” and that the boss was saying, “Hold on, we’re going to win”—meaning that the Nixon team was going to win and she said that the message to the ambassador was “Hold on.” She talked about her boss being in New Mexico. Nixon wasn’t in New Mexico on that day, but his running mate, Spiro Agnew, was.

In this case, her boss, it seems, was Agnew—that would make sense when he said, “We’re going to win”—and it wasn’t John Mitchell, who was running the campaign. On the same day, the South Vietnamese president announced he would not be sending a delegation to Paris for the peace talks. Now, less than 48 hours before, Johnson had halted the bombing of North Vietnam in return for an agreement from the North Vietnamese to do three things, negotiate with the South and Paris, stop [inaudible] civilians in the cities, and respect the demilitarized zone. This announcement by the South Vietnamese president that he wasn’t going to go to Paris, that he was going to—as the boss in the Nixon campaign said—“hold on,” basically undermined the president’s peace initiative. Furious, or concerned, or whatever, Johnson placed a call to the highest-ranking elected Republican in the land, Everett Dirksen.

This is a different phone call than the phone call we started our episode with, which was on the third of November. We’re not quite there yet. We’re at the 31st of October. This is basically Johnson coming in with a brushback pitch, and he says that some of Nixon’s supporters are “getting a little unbalanced and frightened.” They’re calling Hanoi in the North and Saigon in the South with a message that interfered in the negotiations. This is Johnson talking: “The net of it, and it’s despicable, and if it were made public I think it would rock the nation, but the net of it was that if they just hold out a little bit longer, that Nixon’s a lot more sympathetic and that he can kind of … they can do better business with him than they can with their present president.” Well, of course, the present president is President Johnson.

More from Johnson: “Now, I rather doubt Nixon has done any of this, but there’s no question [except which] folks for him are doing it. Very frankly, we’re reading some of the things that are happening.” The delay, said the president, is proving fatal. Here’s Johnson again: “But they’ve got this question, this new formula put in there. Namely, wait on Nixon, and they’re killing 400 or 500 a day waiting on Nixon. Now, these folks I doubt are authorized to speak for Nixon, but they’re going in there, and they range all the way from very attractive women”—in that case he’s talking about Chennault—“to old-line China lobbyists and some people pretty close to him in the business world.” It’s important to note that he makes distinctions between what Nixon may know and what agents on Nixon’s behalf may be doing. This is why Johnson could never blow the whistle out loud—and there were other reasons, which we’ll get to in a minute—he wasn’t sure he had the total goods on Nixon. Here’s a little more from that tape, where the president gets into some odoriferous metaphors.

Johnson: To me, when Nixon’s saying, “I want the war stopped,” that “I’m supporting Johnson,” that “I want him to get peace if he can,” that “I’m not going to pull the rug out of him,” I don’t see how in the hell it could be helped unless he goes to farting under the cover and getting his hand under somebody’s dress.

Dirksen: Yeah.

Johnson: He better keep Mrs. Chennault and all this crowd just tied up for a few days, because he’s got the right formula, and I think he’s done well. I think that Humphrey screwed himself up. John Connally tells me he’s going to lose Texas just because he shimmied on the war.

Dickerson: The president also had a second problem, and his second problem was Hubert Humphrey. Remember that Humphrey’s going around talking about peace in our time, and the South Vietnamese are worried that he’s going to sell them out. They believe that Humphrey will benefit from a bombing pause, and if Humphrey wins they’ll sell them out. No bombing pause, no Humphrey win, no selling them out. The president calls up Humphrey’s campaign manager, a guy named James Rowe, and says basically, “Tell Humphrey to stop going around talking about how this is so politically good for him, that there might be this bombing pause.” Here’s some of that conversation.

Johnson: Rusk said, “Tell Hubert please not to brag, please not to be exuberant, just say ‘I pray for peace, period.’ ”

James Rowe: Yeah.

Johnson: Let the others … they’ll know what it does if you just … if we don’t jump up and down about it. So you watch that.

Rowe: I will. I think his line has been pretty much, “This is the president that’s handling this” and so forth. The only time he showed any jubilation was a little on the … after we were on the plane, I’m afraid a couple of the pool reporters saw him in the back.

Johnson: Yeah, they described him as going up and down the plane being jubilant, exuberant, and of course that just puts the John Towers …. Let me show you what they’re saying about it, you see.

Rowe: Yeah.

Johnson: It’s just … it’s a good excuse for them.

Dickerson: The day before the election—it’s the 4th of November now—the president has been tending these two pots, the Humphrey pot, trying not to keep it on the boil, and the Nixon pot, and all of a sudden knock, knock, knock on the White House doors comes the Christian Science Monitor bureau chief, Seville Davis. Now, the bureau chief didn’t need to meet with the president, which is a good thing, because the president wasn’t there; he was in Texas at his ranch having a good time. Davis was carrying with him a story that was a bombshell. This is the day before the election. His story, which was from a Saigon correspondent, had this as its first paragraph: “Reported political encouragement from the Richard Nixon camp was a significant factor in the last-minute decision of President Thiệu”—this is the South Vietnamese president—“to refuse to send a delegation to the Paris peace talks, at least until the American presidential election is over.”

That morning the president had been riding at his ranch. He returned to find a note saying “Call immediately,” so he did, and he convened a conference call with his secretary of state, Dean Rusk, and his defense secretary, Clifford. “The story can’t get out,” Johnson said. At the very least, it can’t get out from the administration’s side, and the administration can’t validate this story because it will show that they’ve been tapping the phones of an ally. They’re trying to figure out what to do with it, even though they know the story’s absolutely true. In the course of this conversation, Rusk weighs in with the kind of statement you’re supposed to make when you don’t know you’re being recorded, but in Washington where someday everyone will know the truth. I’ll have to read it, because the recording isn’t that clear. In fact, there’s a very funny exchange on this conference call where nobody can hear anybody else. It feels very modern.

Here’s Dean Rusk on this question of whether they can confirm the Christian Science Monitor’s story about collusion between the Nixon campaign, Anna Chennault, and the South Vietnamese government to slow walk this bombing pause: “Well, Mr. President, I have a very definite view on this, for what it’s worth. I do not believe that any president can make any use of interceptions or telephone taps in any way that would involve politics. The moment we cross over that divide, we’re in a different kind of society.” President Johnson assents—not so enthusiastically, but he does say “Yes.” This is interesting, obviously, in the context of any dirt that a campaign gets—whether it’s from a former business partner, or American adversaries/enemies, or the Russians—do you do the right thing with the stuff you’ve been given? In this case, Rusk is saying that even though this incredibly volatile information could sink the Nixon campaign, get Humphrey elected, do things they want, they can’t do it because it would, as he said, put America into being “a different kind of society.”

In politics, in campaigns where people do horrible things, there are those who nevertheless do the right thing. They may falter at various other times in their career, but there are occasionally people in the conversation who feel compelled, because of the norms and values, to not do the expedient and easy thing—even though in this case it would help Humphrey and it would hurt Nixon, and it would be worth telling people, because the next president was essentially committing treason, of a kind, and that’s a good thing for people to know if they’re about to elect him to the presidency. That was a case for letting this out, but nevertheless, Rusk felt that you had to stick to this norm. You can debate whether letting people know beforehand about Nixon was a good idea or not—at the very least it’s debatable—but Rusk was saying, “It’s not debatable. You shouldn’t do it.” The point here is that when faced with an expedient, easy thing that would help you, Rusk was arguing for doing the harder thing.

So was Clark Clifford, the secretary of defense. He chimed in, “I’d go on to another reason also, and that is that I think some elements of the story are so shocking in their nature that I’m wondering whether it would be good for the country to disclose the story and then possibly have a certain individual elected.” That certain individual is Nixon here, of course. “It could cast his whole administration under such doubt that I would think it would be inimical to our country’s interests.” Clifford always liking a 10-cent word, but who are these people? This antiquated pish-posh! Were they wearing powdered wigs, writing with quill pens? “The country’s interests”? What about winning the election, ruining your political opponent? This is soft-soap, patty-cake stuff. Clifford, worried here about the future president’s relationship with the country. He’s a Republican. He’s beating the vice president of the Democratic administration. Nevertheless, this is what Clifford advised, along with Rusk, and the Christian Science Monitor never published the story.

Among other questions in this story is how much the players actually participated in the scheme. In his memoirs, the South Vietnamese ambassador wrote that he only sent two cables to his bosses back home. “While they constituted circumstantial evidence,” Diễm wrote, “for anybody ready to assume the worst, they certainly did not mean that I’d arranged to deal with Republicans.” But here are two of the cables that he sent, which came out later. This one on October 23: “Many Republican friends have contacted me and encouraged us to stand firm. They were alarmed by press reports to the effect that you had already softened your position.” This is on the position of a halt. Another cable sent from the South Vietnamese ambassador: “The longer the pressure situation continues, the more we are favored. I am regularly in touch with the Nixon entourage.” It seems like the South Vietnamese ambassador was a little bit more involved than he suggested. How about Chennault? What do we know about her? What can we say?

Clifford wrote, “What was conveyed to the South Vietnamese president through the Chennault channel may never be fully known, but there was no doubt that she conveyed a simple and authoritative message from the Nixon camp that was probably decisive in convincing President Thiệu to defy President Johnson, thus delaying the negotiations and prolonging the war.” What was Nixon’s role in all of this? Well, he said he had no role in any of this. He told David Frost this in their famous interview, and in a call to Johnson on November 3, Nixon said, “My God, I would never do anything to encourage Saigon not to come to the table. Good God, we want them over in Paris. We’ve got to get them in Paris or you can’t have peace.”

Well, Farrell, in Nixon: The Life, has the goods on the old president. In his research, he found notes from H.R. Haldeman, the top man in Nixon’s campaign and then his chief of staff in the White House. The notes were sealed until 2007. One of the notes has Haldeman writing after a conversation with Nixon, “Keep Anna Chennault working on South Vietnam,” as Nixon ordered at the peak of this business. Elsewhere in his notes, Haldeman writes, “Any other way to monkey wrench it?” Meaning, the peace process. “Anything R. N. [Richard Nixon] can do?” Here is Farrell’s conclusion: “The South Vietnamese president’s foot-dragging was encouraged by signals sent by Nixon and shut a window [to peace] that, with the help of the Soviet Union, Johnson and his aides had believed they had opened. It’s hard not to conclude that of all Richard Nixon’s actions in a lifetime of politics, this was the most reprehensible.” Nixon was directly interfering in the activities of the executive branch and the responsibilities of President Johnson. We’re talking about an ongoing war here, which makes this different from Michael Flynn’s contacts with the Russians at the time that the Obama administration was enacting new sanctions.

The allegation is that Flynn basically sent a signal to the Russians in his conversation with the ambassador that the new administration, the Trump administration, would be softer than the Obama administration. At that point, Trump was already the president-elect, and the Russians obviously weren’t in a hot war in the way the Americans were at war with Vietnam.

Two other little interesting codas here. One is from Chris Whipple’s book, The Gatekeepers, which is about the White House chiefs of staff. He tells a story about Nixon, after having been elected, had a meeting with J. Edgar Hoover. This is how Haldeman recalls that meeting: “The president asked me to be present when Hoover paid his respects. Hoover, florid, rumpled, came into the suite and quickly got down to business. He said that LBJ had ordered the FBI to wiretap Nixon during the campaign. In fact, he told Nixon that Johnson had directed the FBI to bug Nixon’s campaign plane, and that this had been done.”

In truth, no such bug had ever been planted on Nixon’s plane, but Hoover was essentially lying to the president-elect to cleverly play on Nixon’s suspicions—“Oh, I’m giving you little bits of candy to feed your suspicions, and that puts me in your good graces.” This is what’s interesting about Nixon in response. Hoover goes, and Nixon and Haldeman talk about a cup of coffee.

Here’s Haldeman: “I remember the moment clearly, because the next word surprised me. Instead of remarking angrily on the bugging of his plane”—Nixon didn’t know that Hoover was just telling a story here, he took it for real—“Nixon said with some sympathy for Johnson, ‘Well, I don’t blame him. He’s been under such pressure because of the damned war, he’d do anything.’ Nixon paused, holding the cup, and said, ‘I’m not going to end up like LBJ, Bob, holed up in the White House afraid to show my face on the street. I’m going to stop that war fast. I mean it.’” The war in Vietnam would last another four plus years, until August 15, 1973.

There you have Nixon learning about what Hoover said were wiretaps and basically saying, “Oh, no big deal.” In the current Trump administration, President Trump has brought up wiretaps from his predecessor that never existed and has pressed that as a cause against President Obama. Another coda is from the book Chasing Shadows: The Nixon Tapes, the Chennault Affair, and the Origins of the Watergate. This is a great, great argument from Ken Hughes, who says that three years after the election, as the paranoia started to seep in after the Pentagon Papers are released, Nixon feared that his engagement and participation in the Chennault affair, which was essentially, politically treasonous, would be exposed. He was so fearful that he created a secretive investigative unit, the White House Plumbers, to make sure the Chennault stuff never got out—and it was that covert operation that led to Watergate, which led to the cover-up, and we all know where that headed.