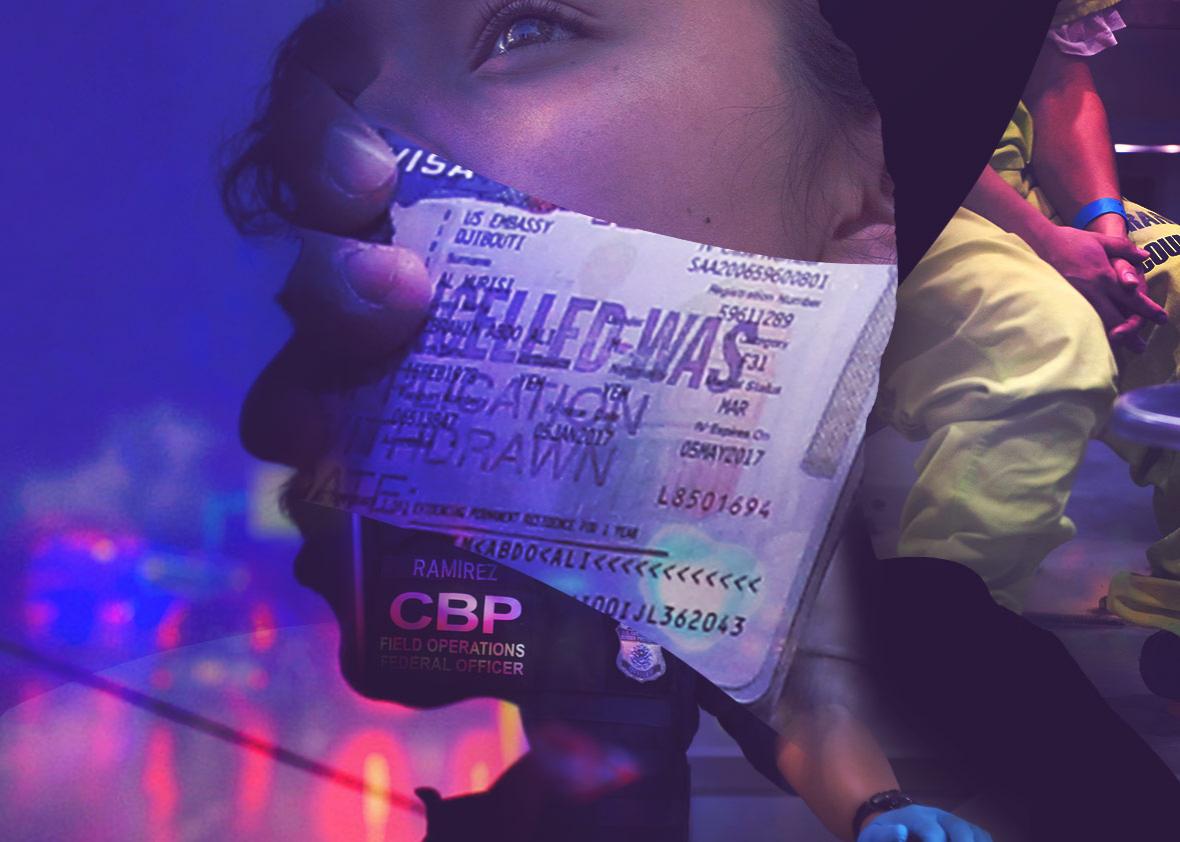

Staying true to his campaign promises to get tough on illegal immigration, President Trump has ordered large-scale raids on immigrant communities across the country.

Among those who are now living in fear are applicants of what’s called a U visa. This visa was designed to protect undocumented immigrants who were victims of domestic violence and other crimes. If they agreed to help law enforcement, they could apply for legal status that would allow them to stay in the country and, eventually, apply for green cards.

But as Nora Caplan-Bricker wrote in a recent cover story for Slate, called “I Wish I Had Never Called the Police,” Trump’s crackdown on undocumented immigrants could endanger the U visa, and the people it protects. In this Slate Extra podcast for Slate Plus members, Caplan-Bricker talks with Chau Tu about the fears and obstacles U visa applicants and holders have faced since Trump came into office.

* * *

This transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Chau Tu: Tell us a little bit more about the U visa—why it was created and who it protects.

Nora Caplan-Bricker: This visa was created in 2000 as part of the Violence Against Women Act. It was created in part to address a problem that undocumented immigrants are frequently targeted for either exploitative work practices or in abusive relationships because it’s so hard for them to speak up about these issues. Predators would target these people knowing that they might be able to get away with it more easily if they targeted an immigrant. The visa exists for victims of crime, and it’s most often used by victims of domestic abuse or sexual crimes, to make it possible for them to come forward and work with law enforcement without having the fear that they will be deported.

Tu: About how many people in the U.S. have the U visa?

Caplan-Bricker: There’s a firm cap on the visa that only 10,000 of them can be granted a year. I believe that the full 10,000 have been awarded since the visa was created almost two decades ago, or at least very close to the full number, but we’re still looking at shy of 200,000 people. It’s not a huge number, and certainly the need for this is so great that there is a backlog of several years where even if U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services approves the visa at this point, they put people on a waiting list where it can sometimes take two to three years for one of those 10,000 visas to free up or for someone to move to the top of the list and get a slot.

Tu: Who are the types of people who have this visa? Is it usually women?

Caplan-Bricker: Yeah, I would say I think that roughly three-quarters of these visas go to victims of either domestic violence or sexual assault or rape, and definitely those are all crimes that for the majority afflict women, also definitely gender non-conforming or queer people. The visa is also broader than that, so there are victims of either violent crimes, felonious assault or extortion in some cases. There is a shortish list of really serious crimes that can qualify a person for this visa, so not all of the people who are receiving it fall into those categories but it is majority women and majority sexual violence.

Tu: You write in your piece that Trump and his crusade against immigration have changed the rules for the U visa, or changed the lives of people that have them or are trying to apply for the visa. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

Caplan-Bricker: Definitely. In a statutory sense, nothing has changed. The visa was created by Congress, it still exists, it still is available. Technically, the rules are the same as they’ve been and hopefully that will continue to be the case. It is the case that I think everyone I’ve talked to in the advocacy community, lawyers, immigrant survivors, people applying for the visa, really feel like on the ground the landscape is changed. In large part that’s because of the way that this administration is conscripting local law enforcement to serve as an extension of ICE and as deportation forces, immigration forces. If you know that your local cop might really be working pretty closely with immigration, then it’s going to be that much scarier to call 911 even in the middle of domestic violence and abuse.

The other thing is just that ICE itself seems to have been emboldened to really try to deport more people and do so quickly. This is a visa that takes a really long time to get, partly because there is so much need and the backlog is so long, that there are now concerns about whether people are going to be able to stay in the country long enough to get one. There’s a question of if you work with law enforcement to help prosecute a violent criminal and get that person off the streets, will you at that point be deported before you get through the whole waiting period to get this visa.

Then there is also fear that the rules themselves, or the way that this is adjudicated, could change because the administration seems to have a lot of interest in law and order rhetoric but really only as it applies to victims defined in a certain way, and immigrant victims don’t totally seem to be part of that picture the way that this administration talks about it.

Tu: How long is that process generally, to apply for one of these visas?

Caplan-Bricker: It really depends in large part, because it depends on legal representation. Like most immigration processes, this one is really complicated. No one could conceivably do it without the help of a lawyer. There are some people out there doing this pro bono, but a lot of the women I talked to who had managed to get a visa, the process was very slow for them because they were paying for a lawyer and they had very little money, and they couldn’t legally work because they had no work authorization, so they were saving up in slow increments and the process was taking a very long time.

Leaving aside those concerns and the fact that the immigration system is as complicated as it is, the actual waiting period for U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to process one of these visa applications at this point is around two years, generally, sometimes longer. Then the waiting list, the phase two where maybe you’ve been approved but there are no visas available, is another one or two years or even more. All in all, this visa wasn’t conceived as something that would take this long to get, but it has become something that takes in general I think four or five years to go through the whole process, even if you’re going as fast as you can.

Tu: What are some of the scenarios that U visa applicants have encountered, especially since Trump?

Caplan-Bricker: I think one of the big things: It’s hard to talk about immigration without just talking about all the fear that exists in immigrant communities right now. I think that’s in a lot of ways the biggest thing. For people who might be applying for a U visa, that means that they’re already in some sort of extremely vulnerable or dangerous situation. Either they’re victims of violence at home or someone is sexually harassing them or exploiting them at work. I think for those people, the fear of coming out of the shadows or calling for help is now much greater than it was. The feeling of being trapped between two impossible situations is more than it was.

I think another concrete thing that a lot of advocates mentioned to me is that when you’re talking in particular about victims of domestic abuse or violence, it’s really common for cross-claims to occur where someone might call in and say, “My spouse has been violent towards me,” but then the abuser might say, “Well, she hit me as well,” and both people might be charged. A new scenario under Trump is that the Trump executive order on immigration, the one that pertains here, mentions specifically people who have been charged with a crime that has not been resolved as people who are prioritized for deportation. Now there’s a lot of fear among lawyers in particular, that anyone who has been charged because of the word of an abuser may be fast-tracked for deportation because of that.

Tu: You talked about some courtroom instances that have been in the news lately, right?

Caplan-Bricker: Yeah, so that’s another scenario where there have been a number of reports from different states of people who were going forward with protective order cases to try to get a restraining order against a violent partner, dropping out of that process because they were afraid of showing up in court because ICE has been hanging out at courthouses in some places looking to possibly apprehend people. It does look like we have our first evidence that people are making the choice to stay in the shadows rather than seek help in a way that might make them more visible to ICE.

Tu: What are the options for U visa applicants now?

Caplan-Bricker: I think the toughest thing in a way is that the options are the same, but the certainty around them is much less. On paper and in actuality, certainly the administration hasn’t said that they’re getting rid of this visa, they haven’t said that they’re going to make things harder for these people. In fact, in my reporting, a spokesperson for ICE told me the opposite, that they’re going to continue respecting some of the memos that were written during the Obama administration saying that they would seek to make it possible for victims of crime to seek these visas and stay in the country as long as they needed to do so, and to have fair hearing and legal process. That still, on paper, is the policy of our country and of the Department of Homeland Security.

That said, there’s this new focus on deporting as many people as possible, whereas under Obama there were pretty clear priorities of who was top priority for deportation, who was low priority. Now many people reading the executive orders feel that everyone is high priority. I think the hard thing for U visa applicants is that no matter who you are, it’s very hard to gauge the level of risk you’re at if you put your name out there. If you put your real name and your picture and your fingerprints and your information on a visa application, it’s hard to be as confident as you would have before that because you’ve had a law-abiding life in this country or you have U.S. citizen-children, or you’ve been here a very long time or you’ve been a victim of crime, you’ve helped law enforcement, whatever all the things in your favor are, it’s just very hard to know how to weigh those against this administration’s stated desire to deport as many people as possible.

Tu: What kind of advice are immigration experts giving to applicants or undocumented immigrants who are looking to get the U visa?

Caplan-Bricker: I think, sadly, the thing I heard over and over again from attorneys was this feeling of being at a loss, that they didn’t really know what advice they could give. I heard from so many people, “This is so hard. All I can say to people is I don’t really know what to tell you. All I can say to people is these are all the ways that I’m uncertain, and you have to make your own decision.” I think attorneys who I spoke to all over the country are definitely feeling that there are just so many unknowns right now, and they can try to weigh those out for a client, and they can try to weigh those against the situation that the client is in at home or the danger that that person is in, they can try to weigh those together, but there isn’t necessarily a way to assure people honestly right now, that an attorney knows what’s going to happen to you in this brave new world of immigration policy.