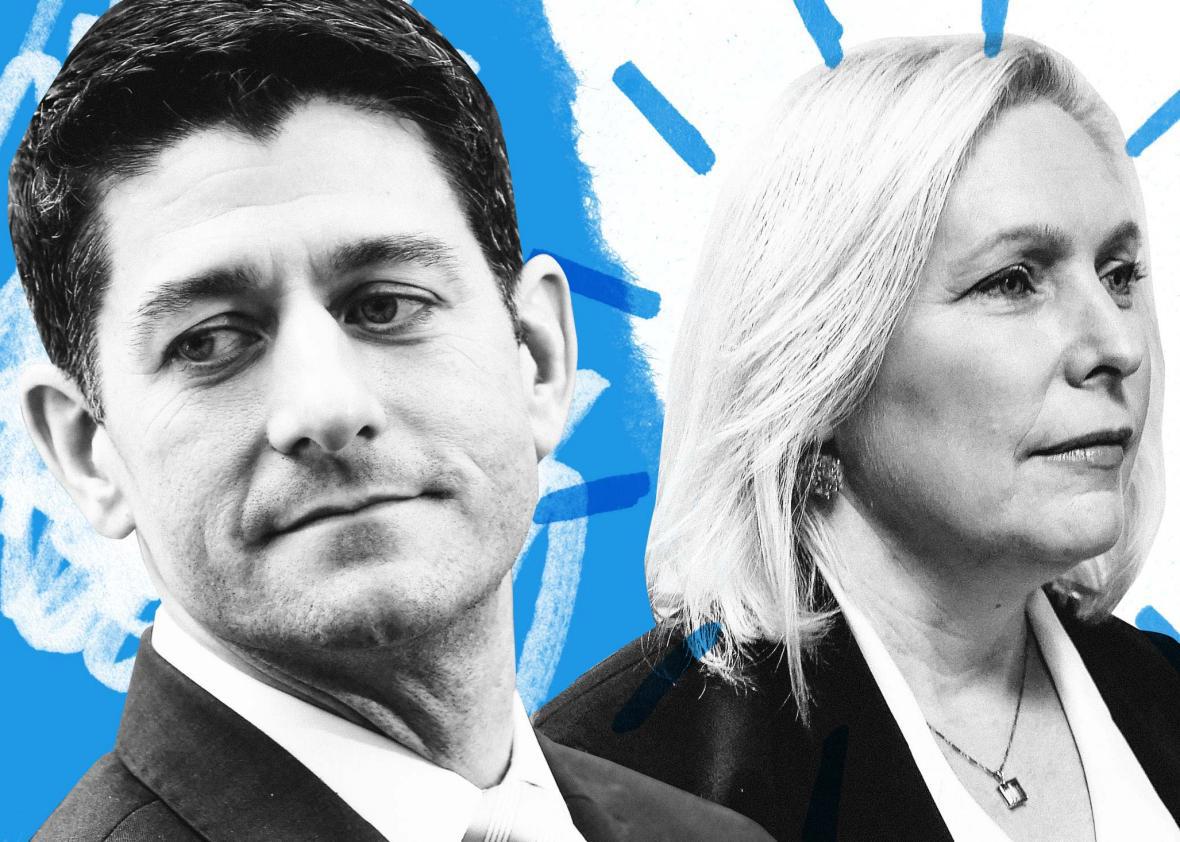

November is still a ways away, but it looks like the midterm elections could bring some intriguing political shifts. A number of establishment congresspeople, including Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, will be hanging up their hats and vacating their seats, and there have been murmurs about how each of the parties should be focusing their ideologies going forward—Should the Democrats turn more left? Should the GOP look for another Trump-like cult figure?

In this S+ Extra podcast—which is exclusive to Slate Plus members—Chau Tu talks with Slate staff writer Osita Nwanevu about identity politics, Ryan’s lasting legacy, and what it’s like covering conservative media.

* * *

This transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Chau Tu: One of the biggest news items on the Hill last week was that House Speaker Paul Ryan is set to retire. This has been rumored for a while, but were you surprised by this news?

Osita Nwanevu: I wasn’t really. It’s never easy being Speaker of the House, I think, in today’s Republican Party. Paul Ryan probably found himself out of step with the way things were going; I don’t think he was enthused to be running things under Trump. He would’ve felt better if Mark Rubio had won the Republican nomination and been president. Trump has thrown a wrench into Republican politics that I don’t think he had expected. It’s not really a surprise that he left; it had been rumored for some time.

What has surprised me has been his willingness to do so while leaving the project that I think he’s been after for the past several years unfinished—I think he really did want to do some kind of major entitlement reform package that didn’t happen. In coverage of his leaving and in his commentary to the media, he’s hinted at the possibility of continuing political work outside of Washington, which suggests to me that he could be doing some more advocacy on this sort of pseudo fiscal hawkery he’s been known for, for the past few years, even after he leaves Congress.

I wasn’t really surprised. It’s not an enviable position to be in. The Republican caucus was a mess before Trump and continues to be, so.

Yeah. Ryan’s legacy really seems to have changed over his tenure. What do you think this actually has to do with his relationship with Trump. Is it only Trump? Do you think it was the [Republican] Party in general changing?

I don’t think it was only Trump. I think you’re seeing a lot of Republican retirements now obviously, because people expect Democrats to do very well, and in an environment where you can expect Democrats to do well, it’ll be harder for Ryan to do things that he wanted. Even if Republicans end up keeping the House, it’ll be at a less legislatively powerful position.

I think it’s Trump, it’s the general climate, it’s the fact that being speaker of the House is a drag in general. I mean, people forget: Paul Ryan’s been in Congress since 1999, I believe. He came into prominence early in the Obama years around 2009, 2010, but he’s been in Congress for a pretty significant amount of time. I think that, that might be part of it too, he’s just sort of sick of things and the political situation’s getting a bit more difficult. I don’t dismiss entirely the explanation he’s given that he wanted to spend more time with him family; people in politics say that a lot to cover up less flattering reasons why they would be leaving, but that’s also a thing.

I think the main thing that people should be thinking about is the extent to which controlling for a Republican Party in the House has become a very difficult task. I think people should be thinking too about the legislative prospects of what Paul Ryan has been trying to do in Congress for several years now.

What do you think his lasting legacy will be after all this?

Well, as I wrote in the piece after his retirement was announced, I think his most important legacy will be the fact that he’s sort of revived entitlement reform as a live discussion in American politics. He, I think, has been the most prominent-seeming fiscal hawk, and I don’t really take his claim to that seriously. As I wrote in the piece, he voted to increase the deficit numerous times under Bush, deficit all of a sudden became a problem, noon January 20, 2010 for him and the rest of the Republican Party. I don’t think that’s what he’s really after, I think he’s interested in cutting social programs mostly.

But, I think his legacy will be the fact that he convinced so many people that he was a serious person when it came to analyzing a bunch of deficit and what would happen with the federal government and the economy if we didn’t take the deficit seriously. He roped in a lot of centrist and liberal journalists in that concern, and he convinced them that he was a wonk. I don’t think his claim to impartial wonkery was ever justified. I think he’s fundamentally an ideologue. He’s somebody whose motivated by a particular understanding of poverty that is at odds with how most Americans view poverty. I think the fact that he got away with sort of dissembling about the consequences of the budget deficit and exaggerating things, and straightforwardly lying about things like Obamacare. All of that I think had big impact on American politics while he was prominent in the Obama years.

Frankly, as I say in the piece, if you want a look at how we got to Trump and how we elected a president who lied too frequently, I think it stems in part from the fact that people like Paul Ryan—who is by no means alone—but people like Paul Ryan have been allowed to get away with not telling the truth about things like the budget deficit and the economic impact of tax cuts for a very long time without any consequences. I think the fact that there wasn’t a norm against the kind of OK line that he did opened the door to people like Trump, to the point where we’re not really equipped to deal with what has happened.

People are doing the right thing now, whenever Trump says things, even live on TV, there will be a caption on the bottom that says, “Trump says this,” [and] in parentheses, “this is actually the truth.” Which, is great but they should’ve been doing that 25 years ago, you know? Maybe we wouldn’t be in the situation where Trump is allowed to build so much credibility.

You talked about how you think that Ryan will take on another role. Obviously people are thinking whether or not he’s going to be going for our presidential run. Do you think that’s going to happen, or what other roles will he take before that?

It would be very surprising to me if Paul Ryan ended up being a viable presidential candidate in the future. I don’t think the Republican Party of today is in a place that really values the kind of image that he tried to put forward. I think again, that’s the part of the reason he’s leaving. The Republican Party has moved to this sort of, very skullduggerous, weird place, where all that matters is this kind of grievance identity politics that Trump taps into. People are not really looking for people who point to charts anymore, if they ever were.

That’s the other thing, I don’t think that Paul Ryan’s was ever that well regarded amongst Republicans in general. He was a vice presidential candidate obviously in 2012 and a lot of people liked him, but I don’t think he was a star figure that people were really enthusiastic about. The people were enthusiastic about Trump and I think in the way that Republican voters are going to come to expect their candidates to be. I think the after-Trump Republican Party is going to be looking for figures who tap the same kind of emotional energy. And Paul Ryan, even though I think he’s been very successful at a sort of policy mission that he’s been pushing, he’s not a really emotionally resonate politician in the same way.

So he’s going to stay in the wonk world then, in a way?

That’s sort of what I expect, yeah. There’s a vast infrastructure of right-wing think tanks in different organizations in that put out reports on what the government should do, and this is what Paul Ryan did while he was in Congress. He’d been putting out his “Path to Prosperity,” which never had any chance whatsoever of ever becoming actual legislation, but he put them out there to drive discussion, and I feel like he could do that very easily outside of Washington, and I think that’s probably what he’ll end up doing.

So, switching gears a little bit, you spent a long time on Slate’s “Today’s in Conservative Media” beat. Can you talk a little bit more about what your process was like for doing that?

Sure. When I started doing that column, the very first thing I did was try to compile a list of publications that I thought would be representative of a pretty broad range of opinion on the right. Or, at least that was my hope in choosing certain publications. So, you know I chose places like National Review, which had been the flagship conservative magazine since the 1950s, 1960s. I chose publications on that end of the spectrum, ranging all of the way to the Gateway Pundit, which is a very pro-Trump, weird blog really. Its articles are often just two embedded tweets and a few lines of commentary with some absurd headline up top.

So, everything in between that, I tried to read and peruse every single day for a couple of hours to sort get a sense of what is being discussed in the conservative media on that day. The other thing I did was I created a list on Twitter of a lot of conservative media accounts because I think that if you’re only looking at what’s published formally, you’re missing a whole lot of discussion and debate. There are times where I’d just see something being discussed on Twitter or an argument between two figures that didn’t have any article attached to it.

People talk a lot about the extent to which people live in media bubbles where they only read publications they agree with. I’m not really troubled by that in the way that other people are—I don’t really take David Brooks’ ramblings about tribalism all that seriously—but I do think it helps to understand what’s going on on the right even if you aren’t really persuaded by their arguments, or even if it’s not going to change your mind, which I don’t think is going to be the case most of the time. I think it’s very important for people to read the sort of swamps that produced Donald Trump, and read also what conservatives are doing about his presidency and what they think.

What do you think you learned most from covering the beat mostly? Did you see any shifts or anything like that?

The thing that surprised me the most was definitely the extent to which pro-Trump people are not really represented at very publications at all. Apart from sets like the Gateway Pundit, like a few Facebook pages, a few other blogs, there really isn’t an organized pro-Trump media in the way that there are establishment conservative outlets like National Review, like Weekly Standard, like RedState. There isn’t sort of any pro-Trump infrastructure equivalent to that, and there aren’t pro-Trump writers really, in places like the National Review.

Maybe I should’ve been surprised by this, but in seeing how popular Trump is amongst the Republican base and watching him as a phenomenon over the past couple of years, I kind of expected that there would be some sort of commensurate media that grow out of that, or a national media that had helped to produce that, but that really doesn’t seem to have been the case. I mean, there’s Breitbart, but even Breitbart has been kind of taken a few swings at Trump here and there every now and then. Obviously it doesn’t have the cache it did at the beginning of the administration at this point.

That’s the thing that I think is important to understand: Trump is sort of operating purely out of gut reaction from voters. There’s not an establishment press pushing his message online. The column represents, as it stands now, what’s being written in online media, and they write the equivalent to Slate. It doesn’t really capture Fox News so much, or at least it didn’t when I was writing it, because Fox News aired in the evenings, the column is published sometime in the afternoon and again, it was intended to reflect what was going on in print and online publications. But, on Fox News obviously Trump has very strong boosters in Tucker Carlson and Sean Hannity.

But, in terms of publications that are like Slate and function within the conservative movement the way that Slate does on the liberal side of things, Trump doesn’t really have that big of a base of support. It’s just sort of establishment Republicans, “Never Trump” Republicans, who will support Trump in insisting that liberals are being too hysterical about certain things he does—that’s the extent to which they’ll support Trump and troll on his behalf. But, in terms of people who are sort of, “Rah, rah, Trump is great, MAGA,” on the same level as the Republican base of voters is, there isn’t really anybody in the major conservative press.

That’s fascinating. That actually also leads into my next question about liberals acting hysterically. There was sort of this talk recently about op-ed pages, especially for publications like the New York Times and the Atlantic, who hired a number of the conservative columnists who were pretty controversial for their comments. You had an argument on Slate about how the fact that liberals do have a right to complain about these hires. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

Yeah, so the big controversy of, I guess a couple weeks ago now, was Kevin Williamson being hired at the Atlantic. They reversed that decision after an outcry over comments he had made about abortion, suggesting that women who have abortions ideally would be criminally punished. He initially set up with punishments up to and including hanging. I think number is that a quarter of American women will have abortions before they’re 45. That’s a big chunk of the population he thinks should be imprisoned, executed. The piece that I wrote wasn’t really about Williamson himself, as much as it was about the conversation that emerged after he was hired about the extent to which liberals and centrists, and liberal and centrist publications, have an obligation to bring on people like Kevin Williamson to represent the conservative views.

My argument was, first of all, we do. There are conservative writers at the Atlantic, the Washington Post, at the New York Times—I counted something like 18. That’s not equality or parity, but the fact of the matter is that centrist publications and liberal publications do a far better job of representing the other side of things than conservative publications do.

The argument that the liberal media is biased, as I say in the piece, has been around for a very, very long time, it was around in the 1950s and the 1960s, when William F. Buckley started up National Review, this is one of the central arguments he made. I don’t see the 1950s and the 1960s as being like, a very progressive or liberal time in which the press was like liberal in the way that we understand it now. If the press was hostile to conservatives then supposedly, I don’t really see an endgame in which liberals can do things that would actually satisfy conservatives. If the press in 1950 or 1960 was too far to the left, there’s really nothing realistically that could be done to satisfy this complaint.

Every time somebody gets mad at a conservative columnist, or some controversy blows up, conservatives will say, “Oh you know, this just proves that liberals aren’t tolerant of conservative views,” which I think is nonsense. I think liberals care a little bit too much, honestly, about representing the right.

And, the people that we bring on to represent are never the kind of people who actually reflect the Republican Party. Kevin Williamson is somebody who wrote a very, very controversial piece for National Review about how people in these parts of the country we consider Trump country, these working class white communities that have had a lot of struggles with the economy that are being ravaged in some places but opioid addiction and all this. He basically said, “You know, these are communities that have failed culturally, and shouldn’t expect too much sympathy.” This is not the kind of person you bring on if the goal of having conservatives in your publication is to reflect what conservatives actually think in general. That’s not a view that’s shared by the majority of the Republican Party.

People like Kevin Williamson are the people who inevitably bring on Never Trump conservatives, establishment conservatives, who don’t really represent any constituency but other conservative writers. If the New York Times, the Atlantic and the Washington Post were serious about representing the conservative views, they’d have someone on like Bill Mitchell. He’s a sort of talk show host who is always saying things like, “Oh you know, if Trump makes a mistake that’s OK, we’re all human, Trump can do no wrong really, and it’s unpatriotic to criticize him.” That’s what the majority of the Republican Party looks like, but there’s no real interest, I think, for good reason in bringing people on who say things like that.

It’s this bind where there’s this very traditionally liberal feeling that you have to expand yourself, or expand your publication so that it’s not a bubble, but you’re expanding it to people who will not actually get you out of that bubble, who hate Trump, or purport to dislike Trump as much as you kind of do.

Right, not expanding in the right way then really?

Right, right.

November’s still quite a bit away, but what are you kind of keeping your eye on as you’re covering the midterms and thinking about that? What do you foresee? The Democrats are projected to do pretty well, right?

They are projected to do pretty well. I think that a lot of seats will be won, the question is whether the Democrats will actually take the House. Democrats seem pretty confident about their chances of doing that, to the point where, you know, you’re reading Politico over the past couple of months, that people are saying Nancy Pelosi should step down if they don’t win a majority. You don’t say things like that unless you’re pretty confident that takeover is within reach.

The problem for them is the people who look at House ratings, people who rate races and people who look at polling and statisticians and political sciences who have been debating over the past couple of months, have come around to say that the Democrats will need to win the popular vote and House elections by something like, between seven and 11 points to win a majority, which is a tall order. It’s certainly possible, but it’s not going to be I think, as easy as people might assume. The polling for generic Democrats looks pretty good, but there’s no district in which somebody named, “Generic Democrat,” is running, you know? It comes down to on the grounds campaigning and a lot of other factors that are going to complicate campaigns as they always do.

But I think Democrats can expect to do well. I’m not really focused on the horse race as much as the broader conversations that are happening now within the Democratic Party, about the strategies that they need to take on and the policy platform that they need to present.

That’s kind of my beat. I started as a staff writer in November and which I pitched what my beat would be initially, it was covering the ideological changes that are sorting shaping American politics right now. So the Democratic Party is having this big conversation about whether it needs to move left, whether it needs to abandon identity politics. The right is having this conversation about whether “Trumpism” is actually ideology, or something that’s affixed to Donald Trump as cult-personality thing. The alt-right is this scary and fascinating force that’s rising on the radar, it seemed to be for a time. There are these debates on campuses being held over identity politics and gender and race. My beat is basically covering all those currents and sort of watching the soup of American politics to see what new things might be emerging.

Do you see any trends?

I think the Democrats are moving left. You’ve seen this rush towards supporting single payer amongst people who are widely considered to be potential in 2020: Pamela Harris, Kirstin Gillibrand, Cory Booker, people like that. Even if the Democratic Party as a whole hasn’t gotten fully on board, there are a lot of people who are now in support of, you know, Bernie Sanders’ vision of what American health care should look like, or something close to that. It’s likely that the person who becomes Democrat nominee in 2020 is going to be somebody who supports single payer. That’s a pretty big deal.

But, even beyond that, I think people are having conversations about things like job guarantee, the idea that the federal government should be the employer of last resort for people if they can’t find jobs, and people have a right to have a job. This is something that was floated in Democratic Party in the 1970s, and it’s making a comeback. Kirstin Gillibrand said that she was open to the idea a couple of weeks ago. Late last summer the Democratic Party released their “Better Deal” plan, which talked about things like minimum wage, antitrust policy, whether we need to break up big companies.

So, there is this shift towards more progressive politics happening. I don’t know how much of that is going to bear on the midterm, because we have all kinds of candidates running. We have traditional Democrats, we have more centrists, we have more progressive candidates. There’s this debate happening right now within the party whether ideologically, this year the Democrats need to move left of stay close to the center or whatever in order to win, I think that’s ultimately going to depend on the district candidates are running in.

I think in terms of the broader future of the Democratic Party, it makes sense to move left. A lot of these issues for reasons that are complicated, but I think the easiest case you can make for more-left politics in the Democratic Party is that they need something that’s going to galvanize people who didn’t come out to vote in the last election. Health care is still the No. 1 concern when people are polled about what they think is the most important issue to be addressed in politics. You have an easier time running on something like where you know, “We’re going to do this big single-payer program, it’s going to be really ambitious.”

Running on things like patching up Obamacare with this or that complicated fix that it takes work to understand, I think that that dynamic is going to encourage more Democrats to move left, the fact that you can kind adopt a kind of bolder language. They’ll be more compelling to people maybe than the kinds of incrementalizating that we saw in the Obama years, and I think Hilary Clinton was known for.

It’s things like that, that I think make it logical to be thinking about bolder solutions. I think it’s going to be very difficult in 2020 for people to run for president without being able to speak in bold terms about where American society needs to go. There are a lot of deep problems. It would take another three podcasts for me to list them all. I think it’s inevitable that people are going to be looking for a bigger vision from the Democratic Party leadership, especially after Bernie Sanders.