Court reporting is usually a fairly predictable beat. But in the age of Trump, legal news has been fast-paced, with back-to-back-to-back controversies: a Supreme Court nomination, possible obstructions of justice, and legally dubious executive orders that drop at a moment’s notice.

In this Slate Extra podcast—which is exclusive to Slate Plus members—Chau Tu talks with staff writer Dahlia Lithwick, who’s been covering the legal beat since the early days of Slate. Lithwick talks about how the pace of the job has changed under Trump, how many Supreme Court justices the president may get to appoint, and what she sees as the biggest legal issues ahead.

***

This transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Chau Tu: So let’s go back: How did you first start covering the courts? Do you remember some of the first cases that you reported on?

Dahlia Lithwick: I started covering the courts because in 1999, which was like six minutes after Slate was founded, the great and wonderful Michael Lewis had been covering the Microsoft trial. He covered part of the trial and not all of it, and they were literally casting around for anyone with a pulse who might be able to step in in the middle of this huge antitrust litigation that was, like, Microsoft pitted against the Justice Department. It was this crazy, wonky case. And I had a pulse; that was pretty much the only thing that recommended me. I had left my law firm, I didn’t know what I was doing, I was sleeping on a friend’s couch in D.C., and David Plotz was like, “Hey, you’re a lawyer, you want to cover this?”

So I covered that, and when it was over, actually, I went to my brother’s house in Canada to nanny for his child and try to figure out what was going to be next, and then Jack Shafer called, and—he was the deputy at the time—was like, “Where did you go? You were funny. Come cover the Supreme Court.” Very shortly after that, Bush v. Gore hit, the 2000 election, and that was a huge story at the Supreme Court. And when I came to the court, I was really the first online journalist who was given a press pass, and so I started doing it kind of funny and narratively, like sportswriting, and it was just a very happy confluence of covering it in a slightly different way at exactly the moment that online news was kind of getting invented.

What are some of the more intense stories that you’ve covered since then?

Well, I think probably through the Bush administration, I did a lot on torture and on Guantánamo and how we were treating detainees and combatants, and that was quite intense. The U.S. attorney firing in that era was really unprecedented, in my experience, and it was a lot of figuring out how the Justice Department worked. And then, you know, covering Obamacare, both challenges for the Affordable Care Act at the court, and then the really fascinating history of the abortion cases that have come to the court. Since February of last year, [there was] Justice Scalia’s death—not just a huge dramatic story in terms of losing this operatic fixture at the court but also what became the Merrick Garland nomination, and the obstruction.

So really, I think, it’s generally a pretty predictable beat, but since Justice Scalia died, right up until the Neil Gorsuch hearings that we really just completed, it’s been a really rollicking, fast-paced story for a beat that’s generally pretty quiet. And I guess the last thing that’s been just really intense has been what I’d call the “airport revolution”: the lawyers who showed up in response to Trump’s travel ban, and the legal response to that has also been quite extraordinary. But I think generally, most legal reporters would tell you that the last couple months have been just one thing detonating after another, and the intensity, even for reporters who are used to fast-breaking legal news, this has been extraordinary.

That actually goes into my next question. It just seems with Trump in the White House, there’s been a lot more legal news concerning his administration, because of his executive orders and his Supreme Court nomination and also the Muslim ban. Is this different from other presidencies at the beginning of their terms? Is this new?

I think it’s different. I mean, I think that there were a lot of fast-breaking legal stories when the Bush administration came in, when the Obama administration came in. But I think this time, partly the confluence of these extreme executive orders—so regardless of whether it was the travel ban, or whether it was the conversation around what the religious liberty order was going to be—I think that these have been unprecedented. Both in terms of being kind of badly lawyered at the front end, so that some of the vetting that should have happened in the administration that didn’t happen then just exploded into these huge legal stories. Then I think the other thing that really does feel unprecedented is that ordinary transitions from one president to another, certainly there are changes in priorities at the Justice Department, there are shifts in how we’re going to enforce things, but I don’t think there’ve been allegations, legal allegations, on the scale of what we’re seeing around the Russia investigation, and possible obstruction of justice around the investigation, genuinely what looks like corruption, or at least Emoluments Clause violations.

And so I think what feels different is both the sort of “drinking from a fire hose” quality, where there’s not a single provision in the Bill of Rights that’s not currently exploding in front of us, but I also think real scrutiny of how this administration has conducted itself, that’s even different from the very, very pinnacle of outrage around the Obama administration. I just don’t remember seeing this kind of feeding frenzy on this scope and scale around what Jeff Sessions knew, what Michael Flynn knew, what Sally Yates said. This stuff does feel demonstrably different from what I’ve seen before.

And obviously, you’ve spoken to a lot of lawyers and legal experts in the past few months—what do they think of Trump?

You know, I don’t think that I could say there’s any one universal reaction. I think that, as with all things, there’s a split between folks who say, “You know, give him a chance, he’s not that bad, you know, fake news,” and liberal lawyers who are horrified, who just think that this has been, you know, anti–free press, anti–free speech, anti–religious separation between church and state. So I think it runs the gamut. I think what I would say that I’ve seen from both lawyers and judges is a certain discomfort with the fast-and-loose quality. You really see this in Republican-appointed judges who have weighed in against the travel ban, you know, I saw it when that case was being argued at the Court of Appeals of the 4th Circuit. Even Republican nominees seem to be very frustrated with the cavalier attitude toward language, the cavalier attitude toward the rule of law.

When Trump attacks the judicial branch, I think whether you are a conservative or a liberal, there is this feeling—at least among the judiciary that I’ve talked to and an awful lot of lawyers—that this is a branch of government that is actually pretty fragile, and the notion that the president can just say, you know, “You’re going to cause the next terror attack, 9th Circuit, see you in court,” or diminishing the stature of federal judges the way he’s repeatedly done, whether it was Judge Curiel before the election, or the 9th Circuit judges who stayed the executive order. I think they all feel a little bit vulnerable, and we even heard then-nominee Neil Gorsuch speaking out, talking about how disheartening it is when the president does that.

So I think I would just probably be careful to say that there are an awful lot of lawyers and judges that I’ve spoken to who say, “You know what? It doesn’t matter, because we got Neil Gorsuch, and he’s great, and all this other stuff is trivial,” but I would say that, overwhelmingly, what I hear is this presidency has been fundamentally destabilizing to the institution of the courts, to the rule of law, to judicial independence and judicial integrity, and that whatever side of the aisle you come down on, it’s just bad for the courts to have someone who both attacks judges and the authority of the courts and who also is so destabilizing to the rule of law.

I thought it was interesting that the sort of early heroes of the Trump resistance, if you will, were the lawyers who showed up with a laptop at an airport, and knew nothing about immigration law, but were just horrified that you could pass what looks like a brazenly unconstitutional Muslim ban, and that “if no one else is going to be there, then I’m there with my Bluebook and my laptop, and I’m going to figure it out.” And that’s, you know, Sally Yates, and that’s Jim Comey. So I do think that there’s an interesting way in which lawyers have become—probably surprising themselves more than anyone—the sort of vanguard of some of the pushback.

You mentioned Neil Gorsuch. You followed his appointment pretty closely. What do you think his role will be on the bench, and how do you think the controversy around his seat will affect his role going forward?

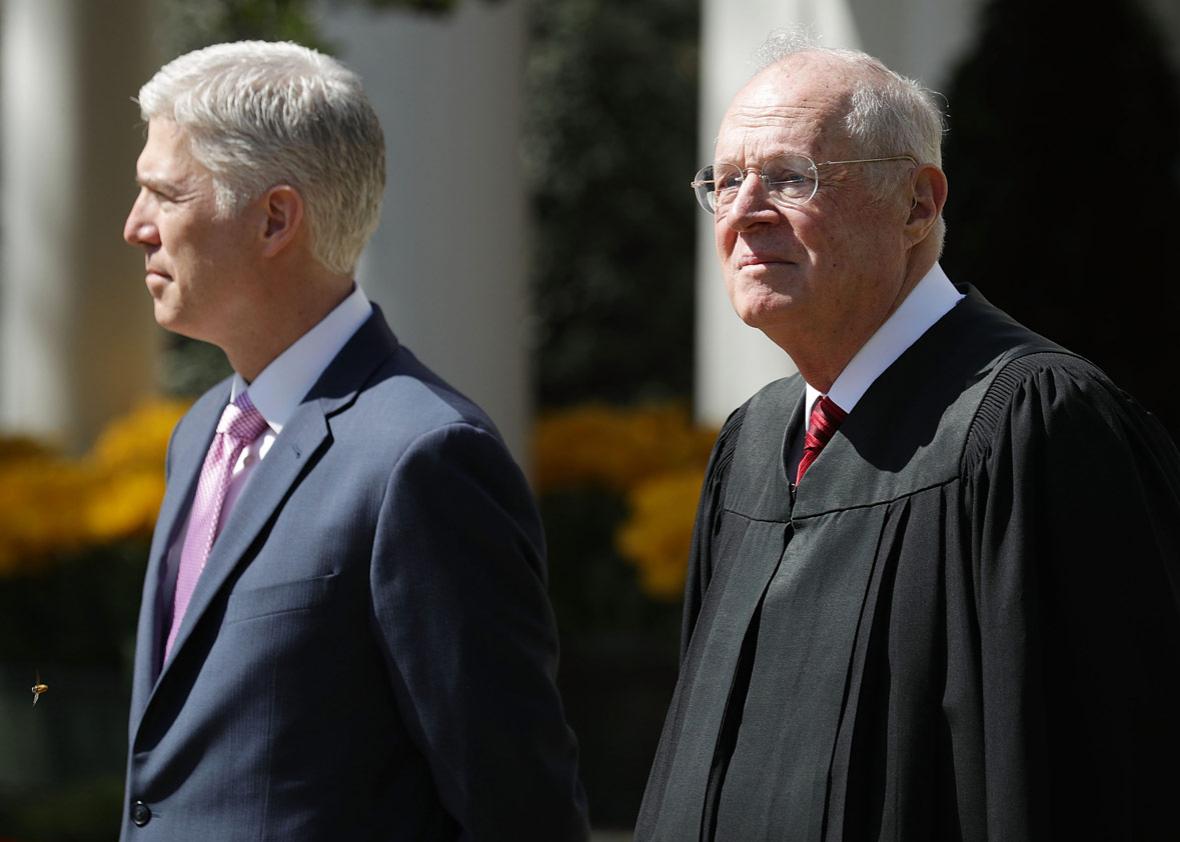

The one useful thing is that he has a lengthy judicial history, so we know where he stands on many issues. We know where he is, certainly, I think, on reproductive rights, we know where he is on religious liberty, we know where he is on campaign finance. There’s a lot of issues on which he’s been pretty open, and I would say even more open in the sort of public discourse, than many other judges. So in some ways, we know where he is, and I think the experts who score these things say, you know, “Is he slightly to the right of Scalia, or slightly to the left of Scalia?” But I don’t think anyone expects him to be a David Souter. He is very much a known quantity, and I think he will be a reliable vote with the court’s conservative wing. And again, I think people can have internecine fights about whether he’s somewhere between Alito and Clarence Thomas, but I don’t think he’s to the left of Elena Kagan. And he’s young, he’s 49, so that will be for decades.

The deeper question you’re asking, and the harder question, is: He’s now survived a filibuster, and Mark Stern at Slate wrote that this is just not a legitimate seat, that it was a stolen seat that belonged to Merrick Garland, and that there was no plausible reason to deny Merrick Garland a confirmation hearing and a vote. And a lot of folks on radio shows that I’ve been on have called in and said, “I just now think of this court as eight justices and a pretender,” and that is really difficult, and I think it’s compounded by the fact that Donald Trump is the person who seated him, and Donald Trump himself is, in the view of some people, illegitimate. So it’s a good question to say what it does going forward to the legitimacy of him and the court.

I think one good thing about the court is that the court tries to really insulate itself from that, and the justices, as you know, have been incredibly, scrupulously careful to not talk about politics, to not get involved in the election. When Ruth Bader Ginsburg spoke openly about Trump last July, she got pushback from the left and the right. So in a strange way, I think the fact that people see the court as, by necessity, being above this kind of fray is going to help Gorsuch. I think it helped him in his hearings. I think the court will work very, very hard to preserve the appearance that this is a legitimate seat, and that the court is a legitimate institution.

Are there any issues that you anticipate might reach the Supreme Court in a few years that are going to be pretty major?

I think so. I think that there’s a lot of interest right now. The court’s been declining to take Second Amendment cases that really carefully delineate the scope of gun rights in the country. They’re going to, I think, inevitably have to take that fairly soon. I think Donald Trump is going to raise a lot of questions about executive power and the scope of the president’s powers. I think there’s going to be really interesting blue state challenges to the president’s power that are going to invoke all kinds of interesting states’ rights claims, the kinds of things red states were doing in the Obama era.

And I do think that a central issue that the court is going to have to tackle sooner rather than later is this clash that we’re seeing between basic civil rights laws on the one hand and religious liberty claims on the other. And so cases that started as Hobby Lobby, the cake-baker cases, people who don’t want to serve same-sex couples, I think all those cases are going to start to really, really take on a major role in this question of how much does a religious dissenter get to opt out of American civil rights protections, and I think that those are really going to be, in a big way, shaped by the presence of Justice Gorsuch on the bench.

And there’s also the possibility that Trump might be able to appoint another Supreme Court justice during his term. Do you want to talk a little bit about that?

Well, Ruth Bader Ginsburg is 84, Anthony Kennedy is 80, Steve Breyer is 78, so the actuarial tables would suggest that there might be one, two, three appointments in a four-year term, so I think it’s a very real possibility. There have been a lot of rumors swirling in the last few months that Justice Anthony Kennedy wants to step down as early as this spring. There’s been a little bit of hushed rumors that Clarence Thomas also wants to step down. Obviously, if Clarence Thomas or another of the court’s conservatives leaves the bench, it won’t be a substantial or significant shift on the bench.

I think that what everybody is watching for is if either Justice Kennedy, who is traditionally at the very center of generally a polarized 4–4 court, if he steps down, it’s going to be a sea change in the composition of the court, and that’s when I think, really, really, you’re going to be hearing people talk about the court changing for decades. And same with Ruth Bader Ginsburg. If Justice Ginsburg were to step down in the next few years, I think you would be looking at really a conservative majority fixed on the court for decades, and it is very much something that folks are watching. It’s probably worth pointing out that an awful lot of people who voted for Trump, kind of held their nose and voted for Trump, did so exactly because they knew that on an aging court, there was a possibility of making lasting change that will affect every part of American life, and I think in a deep, deep sense, that’s what they’re hoping is going to happen this summer and maybe the summer after.

So far, the courts have taken an active role in blocking some of the White House’s executive orders. Do you think the administration is starting to figure out how to draw these laws so they can pass judicial muster?

Oh, absolutely. I mean, we can even see in the difference between the first effort at the travel ban and Travel Ban 2.0 the differences that lawyers will make, and I think the same is true of the executive order. Initial drafts of the executive order around religious liberty and tax status for churches were very much lawyered up before they showed up in final. So it’s pretty clear that those initial days, when we don’t even know who vetted, if any lawyers vetted the original draft of the travel ban, those days are over, and now good lawyers are looking at them and trying to make them constitutionally sound. So I think there’s no doubt that there are lawyers on the case.

I think, really, one of the fascinating questions now has become how much does what the courts are calling the sort of “taint” of those initial efforts extend into successive attempts to do it right? So, particularly in the travel ban cases, what we heard in both oral arguments at the 4th Circuit and the 9th Circuit in the last few weeks was judges saying, “Well, I know they got it right on paper this time—like, it’s clear that they showed it to a lawyer this time—but what do we make of the first travel ban? What do we make of Trump’s campaign promises? How much does it matter what his intent was and what his explicit claims about what he was going to do [were]?”

So it’s a fascinating ontological question right now, that judges are having to ask themselves whether their role as judges is to pierce the four corners of what’s written on this order, and how much they need to just say, “I just have to live with this, even though I know what the original intent was.” And that is such a strange thing. You can see the judges who are hearing these cases are just in agonies over this existential question of, “We all know what Trump was trying to do, but good lawyers have told him not to write it and say it. How much do we take that into account?”

What other big stories are you following right now?

There’s just lots going on. Last week was the 25th Amendment and whether that was a sound basis for getting rid of this president. You know, the Russia inquiry, and the, I think, increasingly at least somewhat credible claims that there’s been genuine obstruction around the Russia probe is a massive legal story. I think that other stories that we’re just following, trying to stay on top of, are [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] and immigration stories. We’re trying to stay on top of what’s going on in terms of the Justice Department and its shift in priorities and what that’s going to mean.

I think that there are just so many really moving parts of this administration, it’s easy, I think, to get really, really caught up in the day-to-day soap opera of what has gone on in terms of the Comey firing and the special counsel, but I think just day to day, there’s also just a tremendous amount of legal change, in terms of what the Justice Department is going to enforce, how they’re going to enforce it, and just generally, I think it’s wearying, and yet it’s sort of incumbent on us not to be weary. And it’s also worth pointing out that President Trump has so many judicial vacancies to fill on the lower courts that don’t get attention, but it’s worth watching what kinds of folks he puts up for the lower district courts, for the circuit courts of appeal, because he has the ability to reshape the federal bench, again, for decades to come. All of this is stuff we have to be vigilant and be watching and try not to get so exhausted that we just drink instead.