This episode’s transcript of Amicus, our legal affairs podcast, is free and available for all to read. To gain access to all other transcripts of Amicus, which is a benefit available exclusively for Slate Plus members, sign up for a free trial membership at slate.com/amicusplus.

What follows is the transcript for the second part of Episode 47 in which Slate’s Dahlia Lithwick speaks with U.S. Solicitor General Donald Verrilli and debriefs on the affirmative action ruling.

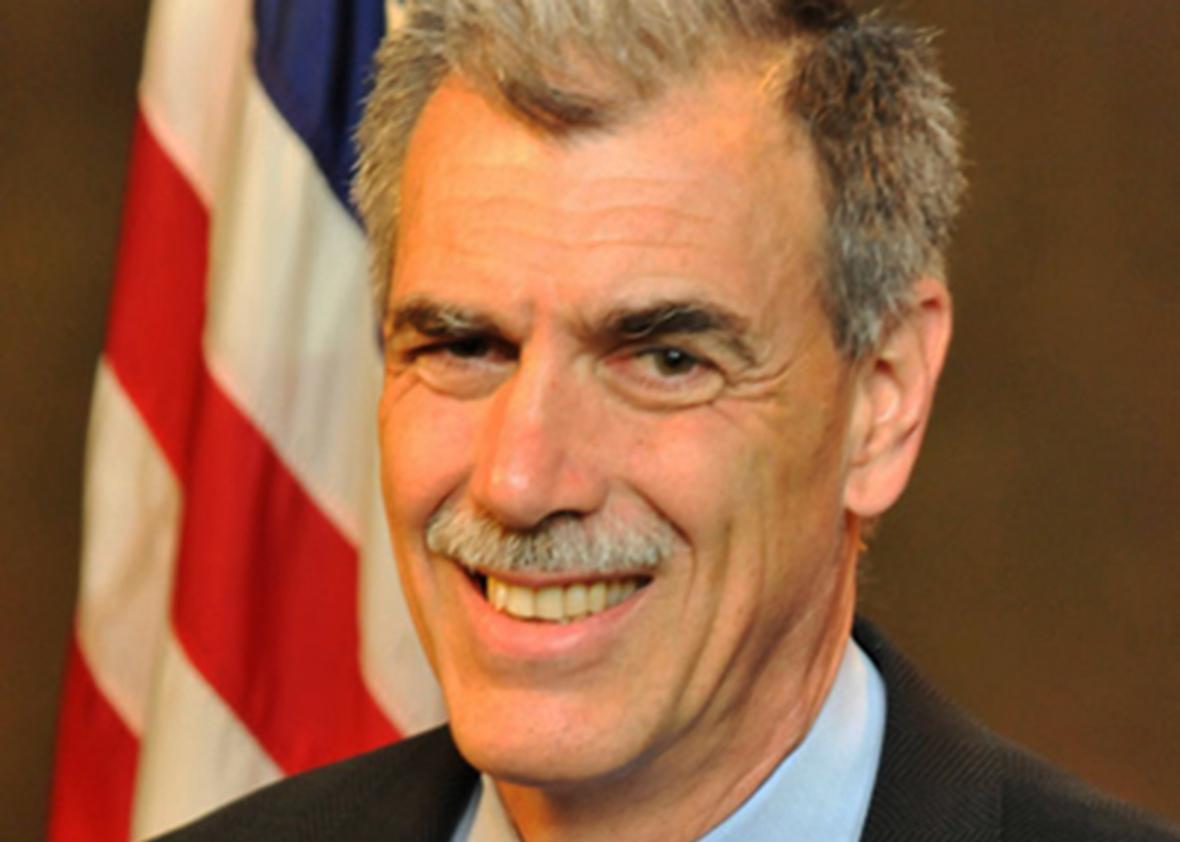

Verrilli stepped down as solicitor general on Friday after five years of representing the United States at the Supreme Court. During his time in office, Verrilli argued some of the country’s most high-profile, landmark cases on affirmative action, Obamacare, and gay marriage. But before he leaves, Lithwick checks in to hear about his experiences, struggles, and proudest moments in the court.

To learn more about Amicus, click here.

Dahlia Lithwick: We are taping today’s show on Friday, June 24—a day that happens to mark the very last day on the job for United States Solicitor General Donald Verrilli. Verrilli has argued 37 cases in five years on behalf of the Obama administration. Many of them turned out to be truly landmark cases. He is the seventh-longest-serving solicitor general in American history, and he was kind enough to swing by the Slate podcasting studio before heading out on a very well-earned vacation in an undisclosed location.

Don Verrilli graduated from Yale and Columbia Law School, he clerked for Justice William Brennan, and he’s argued a dozen cases before the Supreme Court before he joined the Justice Department in 2009. So, solicitor general Don Verrilli, welcome to Amicus.

Donald Verrilli: Thank you, Dahlia. I love Amicus. It’s the way I figure out what’s really going on in the Supreme Court. I’m a devoted fan.

Lithwick: That’s quite worrisome.

So, I want to start by asking you to help our listeners understand what the solicitor general does, because I think people know that you wear that nice frock coat and you argue cases, but your job is actually much more involved than that. It’s sometimes described as the “10th justice.”

Verrilli: Not by any real justices, of course.

Lithwick: No justice has said that. So, can you help talk through what the SG does and maybe talk a little bit about the part of your job we don’t see, which is helping determine where the Administration’s going to land on cases?

Verrilli: Right. Yeah. You’re exactly right about that. The part that the public sees is the arguments up at the podium and the briefs that we file. But a significant part of the job—in fact, I’d say I spend more of my time on this part of the job, which is deciding what the position of the United States will be in the cases that we’re going to be participating in before the court.

We’ve got to make that decision over and over again in the course of a term. You know, when we’re not a party, we sometimes file as amicus, as friend of the court, 25, 30 times a term, sometimes more. And in each of those cases, we’ve got to decide what position the government’s going to take. And that is the solicitor general’s job to make that decision.

And quite often there’s a great deal of disagreement within the executive branch about what we should do. Some cases are pretty straightforward, but a lot of them aren’t. I’ll give you one example that has come up often during my tenure. The cases involving the question of whether U.S. courts should be open to claims of international human rights violations brought by foreign persons against foreign government officials. And the State Department on the one side has got a very consistent and powerful view that U.S. courts should be open to those claims because there needs to be a place in the world where they can be brought. And those human rights norms ought to be real and enforceable, and we ought to be a beacon to the world. And then on the other side you’ve got the Defense Department and the intelligence community saying, “Well, yes, but if we allow our courts to be open to suits against foreign government officials, we’re not going to have a leg to stand on when, say, Nigeria or Pakistan or some other nation hauls an intelligence officer or a military officer into their courts and tries to prosecute them.” And so, you know, you’ve got very strong conflicting views, and it falls to the SG to make a judgment about how you’re going to reconcile those views in any given case.

Lithwick: Can you talk a little bit about the extent to which you have to communicate with the president on issues that may be incredibly important to him? And I ask partly because you’re in this unique posture where the president is a Constitutional scholar in his own right. You’re not dealing with somebody who doesn’t know stuff. How much did that inflect on the way you had to do your job? Were you debating footnotes with the president at 3 a.m.?

Verrilli: Yeah, so surprisingly little, actually. I had a great deal of independence from the president and the White House during the entirety of my five years. And I’m not sure exactly what that is, but our friend, Walter Dellinger, has a theory about it, and I think he’s probably right. And the theory starts with the fact that I worked in the White House for a year and a half before coming over to the position of SG. And because of that, when I was nominated, there was some chatter out there that, “Oh. They’re putting a political hack in. This has never happened before.” And Walter said at the time, “Well, no, Don. You’re going to have more independence than SGs normally do because they know you over there.”

And I do think it’s true that a huge amount of the oversight that the White House engages in with respect to the Executive Branch is out of fear that somebody’s going to do something crazy and drive the president off a cliff. So, they want to get out in front of it. And although I’ve never spoken to anybody over there about it, I think really what happened with me was that they knew me. I’d worked closely with them for a year and a half. And, you know, if you’ve ever been in the West Wing, it’s like a little rabbit warren. Everybody’s crammed in there on top of each other, and you’re eating breakfast, lunch, and dinner at the mess with people. And so you really get to know each other very well. So, I think they just weren’t worried.

So, they left me a really wide berth. You know, I don’t go over there and have meetings and tell them what I’m doing. I don’t send them reports. Maybe two or three cases a term where I think they might be surprised at what we’re going to do, I’ll call them up and give the White House Counsel a heads up. And then I do a little bit of hand-holding on the big cases. You know, like health care, I’ll call over and say, “Don’t worry. We’ve got it under control. We have the best people working on it. We’re on schedule. Stay calm.” So, those kinds of things.

There was only really one time that I had a substantive interaction with the president directly, and that was in 2013 when we were deciding whether to file a brief in the first gay marriage case, the Perry against Hollingsworth case. That was a weighty decision about whether the United States government was going to come in and say that heightened scrutiny ought to apply and some state bans on same-sex marriage ought to be unconstitutional. And that was the one time in my tenure where I thought I ought not make this decision without talking to the president.

Lithwick: Why’s that?

Verrilli: Because it was such a weighty decision to—you know, it was a decision of profound consequence. It might not have been quite the equal of the United States deciding to participate in Brown against Board of Education, but it was up there. You know, it was that kind of a decision. And in the past, presidents had been consulted about those kinds of decisions by SGs, and I thought it was the right thing to do.

So, I went over with the Attorney General, and we met with the president. And we ended up meeting for about an hour. And White House counsel, Kathy Ruemmler was there too. And it was really one of the high points of my time in office. It was an amazing conversation. It was an hour long, and the president wasn’t prepared in the sense that he didn’t realize we were coming over to talk about this. So, he hadn’t prepped for the meeting. And yet we had this incredible conversation. He was just pulling the relevant cases out of his head and distinguishing this and distinguishing that and predicting, as it turns out accurately, some of the questions that Justice Scalia was going to ask at oral argument. And it was just a phenomenal conversation and, you know, focused on, really in addition to all this doctrinal law professor stuff, the really big questions of whether we ought to make a judgment that this should be left to the political process or whether we ought to make a judgment that we should intervene and try to establish a fundamental right here. And it was, you know, at one point the president said, “You know, everybody my daughters’ age has already made their minds up about this. Time is going to cure this.”

But then eventually we, you know, worked around to the position that there was some concern that it was going to end up, that the country would end up in the way it did with respect to race in that you have the majority of the country finding and respecting marriage equality but a subset of the country not. And then do we really want to have a nation divided like that? It was really an amazing discussion. At the end of it, he still hadn’t made up his mind. So, I had to wait a week or so to get a word back about what we should file. So, that one time was just an incredible engagement. But that was the one and only time that I had a discussion like that with the president.

Lithwick: I want to stay on the subject of marriage equality because this is the part of the show that everybody loves but you hate if you’re the one who has to hear your own voice. But we get to play clips of you back at you. And I want to talk a little bit about the marriage equality cases because certainly that’s, I think, what you’ll be remembered for. And it’s interesting. You know, I think it’s fair to say, you know, you did a really good job in Windsor. But, boy, Obergefell was—you—something—it seemed as though something really transcendent happened to you. I want to play you a little bit of you in Obergefell, and let’s talk about it:

Verrilli: The decision to leave this to the political process is going to impose enormous costs that this court thought were costs of constitutional stature in Windsor. Thousands and thousands of people are going to live out their lives and go to their deaths without their states ever recognizing the equal dignity of their relationships.

Justice Kennedy: Well, you could’ve said the same thing ten years ago or so when we had Lawrence. Haven’t we learned a tremendous amount since, well, since Lawrence just in the last 10 years?”

Verrilli: Yes. And, your honor, I actually think that’s quite a critical point that goes to the questions that Your Honor was asking earlier. I do think Lawrence was an important catalyst that has brought us to where we are today. And I think what Lawrence did was provide an assurance that gay and lesbian couples could live openly in society as free people and start families and raise families and participate fully in their communities without fear. And two things flowed from that, I think. One is that has brought us to the point where we understand now in a way even that we did not fully understand in Lawrence, that gay and lesbian people and gay and lesbian couples are full and equal members of the community. And what we once thought of as necessary and proper reasons for ostracizing and marginalizing gay people, we now understand do not justify that kind of oppression.

Lithwick: This was an amazing moment because it was—it felt as though, and I think a lot of listeners felt as though, it was you saying to Justice Kennedy, “We’re not even where we were at Lawrence. We’re in a really different place. We’re at a different place than we were two years ago.” And there was an extent to which you were putting into words the thing that everybody was thinking, which is, we need to get Justice Kennedy from where he was just in Windsor to where he needs to be right now. Was that a conscious thing? Or did you just in that moment say, “I need to say what I need to say to tell him it’s time to pull the trigger”?

Verrilli: It was a conscious thing, but it was also based on the experience of arguing Windsor and Perry two years earlier or three years earlier, whenever it was. You know, in those cases, in both of them, I stuck pretty much to doctrinal arguments. And that should be heightened scrutiny, as lawyers say, under the Equal Protection Clause.

And, therefore, you ought to strike these laws down. But I felt like those doctrinal arguments weren’t really answering what was at stake. You know, really the questions in the case were: Why should the court be doing this rather than the political process, and why should it happen now rather than sometime in the future? And I just decided, so, it was a conscious choice this time around that I was going to talk about the big questions that really were at issue and leave the doctrine on the side.

And one of the big questions at issue was: Why now? You know, are we ready for this? Is this the time to do this? And so the answer about why it was the time to do this—I did think Justice Kennedy’s opinion on Lawrence was critical to that because it really, what Lawrence in one sense was, of course, about consensual sex being something that the government can’t regulate. But really in a more fundamental sense, what it was saying, “Look. Gay people are normal people, and they get to live normal lives. They’re not criminals by virtue of the fact of being gay.” And that establishing that premise, it changed society, and that that society change made it not only appropriate but imperative to be considering the marriage issue now. Because if people can live openly and be equal, then you have to have a pretty strong reason to say they can’t get married. So, it really it was a plan, actually, to do that.

Lithwick: And I guess we should say for anybody who’s been living under a rock for a year you prevailed in Obergefell. And that really, I think, becomes a signal case in this Administration. When Obergefell came down, I mean I was sitting in the chamber too, and there was just a palpable sense of relief everywhere, not just, you know, the rows of advocates who’d devoted their careers to this but the folks outside, The White House lit up in rainbow colors. Was that a moment that you will think back on in your career and say, “That was a thing that I -”

Verrilli: Oh, certainly, certainly. I mean I don’t want to take credit for it. You know, there was a huge movement that led up to that, and I played a small role in the great scheme of things. But it was really a privilege to get to do it. And it was an amazing moment when the decision came down. It was an amazing thing, to be there and just to feel that palpable sense of the country being different right at that moment. It was an incredible thing.

Lithwick: Yeah. I want to play a little audio that’s going to make you less happy. This is from your argument in Shelby County. This was a case you lost on the Voting Rights Act, and I think the effect has been to eviscerate significant parts of the Voting Rights Act. There’s a lot of talk in that case about, you know, Justice Antonin Scalia talking about racial entitlement, but I want to play for you a clip where you and John Roberts are having a colloquy that I thought was very dramatic. So, let’s play it and then talk about it:

Justice John Roberts: General, is it the government’s submission that the citizens in the South are more racists than citizens in the North?

Verrilli: It is not, and I do not know the answer to that, Your Honor, but I do think it was reasonable for—

Justice John Roberts: Well, which is it? You said it is not, and you don’t know the answer to it.

Verrilli: I … I … it’s not our submission. As an objective matter, I don’t know the answer to that question. But what I do know is that Congress had before it evidence that there was a continuing need based on …

Lithwick: Let’s talk about that. What’s the correct answer to the question, “Is it the government’s submission that citizens in the South are just more racist than citizens in the North?” And he had pointed out to you earlier that Massachusetts seems to be awfully racist too. What do you do when you get a question like that? I guess what I’m asking is, this was something you couldn’t have answered.

Verrilli: Correct. There was no possible way that I could suggest that it was our submission. And so I tried to at that moment move the conversation to what I thought was the relevant legal question, which was: Who gets to decide? Does Congress get to decide it or the court? And that the Congress did have good reasons for thinking we needed to continue with the Section 5 evaluation of electoral changes in these states given a long history there, and that that could be a perfectly reasonable judgment for Congress to make wholly apart from any sense that one part of the country has more racists than other parts of the country do. But that was, you know, you’re right. That was quite a moment. I was in a tough spot there with that question.

Lithwick: And I guess I want to ask just because you’re here and you’re about to go off to Europe. But how much are you prepared? I know you moot these and you moot these, but were you prepared for that question? “Is the South just racist?” How much of some of these moments where you’re just boxed in and there’s no great answer are you prepared for? And what percentage of your time do you spend standing up there going, “Uh-oh. I should’ve mooted this question,”?

Verrilli: Yeah. You know, the moot court process in our office when we get ready, we—everybody, including the SG, does two moot courts for each argument. And they are phenomenal, and they predict 90 percent of the questions that I get asked, at least 90 percent. And so in some sense, a question like that was one I was prepared for. But, you know, sometimes one of the justices, because they’re, you know, they’re brilliant lawyers themselves, can put the question in a particular way so that, even if you’ve prepared to talk about the topic, the question is put in such an excruciatingly difficult way that there’s just no good way to handle it.

And that was one such example. You know, there was this point about, you know, the basic point there as well—this statute treats some parts of the country different from others, and what’s the justification for that? Well, you know, I had eight million things to say about that, but he put it in such a sharp, excruciating way that it was just very hard to handle it effectively.

Lithwick: OK. Well, to apologize for the PTSD of the last question, we’re going to move on to what I think is considered your greatest achievement, which is winning not just one but two cases that involved the Affordable Care Act.

The first was in 2012 and then again last year in King v. Burwell. That was the challenge to the subsidy provision. Now, I am not going to do what everybody has done in your exit interviews. I am not asking you about Watergate, which is when you took a sip of water and America went insane. I will tell you that that was the only question I answered as a journalist, was, “Why was he drinking water? So, we’re not going to talk about that, and we’re not going to play it. But I do want to ask you this question because it’s related to that.

How much does the press just get it wrong when they speculate on oral argument? Because I think it’s fair to say everybody said, “Boy, in that first Obamacare case, boy, not only the water but, you know, Verrilli wasn’t ready. He didn’t know what was going on.” And they were absolutely wrong. How much does our getting it wrong—A) I guess I just want to ask the visceral question of how much does it matter to you? Do you care? And then I just want to ask how much it sort of affects the general conversation about the law? Because it feels like all we talked about for a couple of days was you.

Verrilli: Yeah. I do think, I mean just to think about that argument, you know, the beginning part of it did not go so well. But it was an hour long, and I think what happened is that everybody’s impressions got formed in those first few minutes. And I felt like, by the latter part of it, I kind of clawed my way back into the discussion. But everybody’s impressions were set at the beginning. And wholly apart from me and whether I was good or bad, you know, there were a lot of hostile questions.

And so I think there was some reason based on that to think that the law was at more risk than maybe some people thought coming in. But I do think it matters some in that, and this case is a good example of it, I think a lot of folks covering the court, a lot of the court-watchers, assumed going in that this was going to be a pretty easy case for the government. And then all of a sudden, woah. There was a lot of hostility.

And I think that jarring of expectations led to the way the case was covered after. And, you know, I just think that’s inevitable. That’s the way it’s going to be, and it’s fine. And I wouldn’t criticize anybody for doing it. People have got to make their best calls in what they think about a case when they’re covering it. But I do think the lesson there, and I guess stating the obvious, that oral argument can as often send a false signal as an accurate signal about where the thing is going.

And I do think that the instant nature of the reaction now, I do think it has an effect, that people’s instant reactions to things are valid and valuable. But they’re not always right, and they’re not always capturing the full reality. And then, you know, you watch what happens on Twitter. One thing leads to another very quickly. And in an ironic sense, even though it’s such a democratic form of communication, there’s a funny way in which it leads to a hardening of a conventional wisdom much more quickly than might happen if you were reflecting on it a little more.

Lithwick: I think that’s really true. And I think, maybe to stay on the Affordable Care cases, because we focused so much on that one sip of water, we forgot to talk about the fact that you did something really important, which is introduce the tax argument. And almost nobody covered it, right? It was like kind of this turns out to be the argument that prevails with John Roberts. Let’s listen to it. This is you talking about tax:

Verrilli: And so I don’t think this is a situation where you can say that Congress was avoiding any mention of the tax power. It’d be one thing if Congress explicitly disavowed an exercise of the tax power. But given that it hasn’t done so, it seems to me that it’s— not only is it fair to read this as an exercise of the tax power, but this court has got an obligation to construe it as an exercise of the tax power if it can be upheld on that basis.

Justice John Roberts: Well, why didn’t Congress call it a tax, then? Are you telling me they thought of it as a tax, they defended it on the tax power? Why didn’t they say it was a tax?

Verrilli: They might have thought, Your Honor, that calling it a penalty, as they did, would make it more effective in accomplishing its objectives. But it is, in the Internal Revenue Code, it is collected by the IRS on April 15. I don’t think …

Lithwick: So, I wonder if you’ll talk a little bit about—because this is one inside baseball thing that hasn’t been reported, that you pushed to call it a tax and that you had some blowback from people who said, “Don’t. Do not do this. This is a big mistake.”

Talk a little bit about the extent to which—were you just pressured? Or were you just being kind of smart and strategic when you said, “I’m going to call this a tax, and let’s see if we can make something stick”?

Verrilli: So, this whole tax thing happened in two stages. The first stage was before I was SG. It was when I was at the White House. And I was working in the Counsel’s Office right when the law was enacted in March of 2010. And you remember all these lawsuits got filed like the day the law was enacted. And very quickly the lawyers in the Justice Department pulled together a set of recommendations about how we ought to defend the law as a constitutional matter. And it was the lawyers in the Justice Department who thought that it was important to include the tax power argument as part of it. And I was in the Counsel’s Office, and so it fell to me to write the memo to the president, making a recommendation that we needed to do that. And there was some blowback from the political folks in two ways. One was that, you remember, it’s an election year. It’s the spring of 2012, that the Obama administration would be embracing the argument that the Affordable Care Act was a tax, and that was going to, itself, be a political albatross.

And then beyond that, the president had been asked some questions by George Stephanopoulos on a news show about whether it was a tax. And he had given an answer that you might read as him saying it wasn’t a tax. I think what he said was, “It isn’t a tax increase on all Americans.” But, fair enough, you know, you could infer that he was saying it wasn’t a tax. And, you know, I made the recommendation that we needed to include this argument because it was a useful hedge or fallback. It was a narrower constitutional theory to uphold the statute that didn’t have as many implications for how much federal government power there would be as the broader Commerce Clause theory.

And, you know, the president just approved it, period. So that initial thing happened immediately. I don’t know what went through the president’s mind, but we sent the memo in one night. And the next morning, the Approved box was checked. And so, you know, he didn’t seem to lose a lot of sleep over making the judgment that we would include the argument. Typical of the president, I think, that he was making the calculation about what was right and not what was politically expedient, and what was smart.

So, that was sort of Stage 1. Stage 2 was when I got to the SG’s Office. We had included that argument all along. But the more I worked on the cases as we were shaping them up for the Supreme Court, the better that argument seemed to me. Some arguments, you work on them. The more you work on them, the worse they seem. Some arguments, you work on them. And the more you work on them, the better they seem. And this one was in the second category. And then that—my instinct about that was bolstered by an opinion that Judge Brett Kavanaugh from the D.C. Circuit issued some months before the Supreme Court case. And he’s a brilliant, brilliant judge and one of the most-distinguished conservative jurists in the country. And he wrote an opinion where he didn’t embrace the idea that it was a constitutional exercise of the tax power, but he wrote an opinion that said, “Boy, it sure looks like a tax.”

And while I thought, well, jeez, if Brett Kavanaugh is looking at it that way, that tells me something. And so my own instincts and then that sort of validation of them made me think, we’ve got to really put a lot more energy into this. And so we pushed it pretty hard. And I did think at oral argument too that I was just bound and determined to talk about it. And it was an hour-long argument, unusually long argument, hour-long per side—about 40 or 45 minutes in, I started saying, “I want to talk about the tax power now.” And I couldn’t get off the Commerce Clause for a while. And then eventually Justice Sotomayor said—I think, if I’m remembering correctly, I think it was her. She said, “Let’s talk—you want to talk about the tax power.”

And I got like a 10-minute run on the tax power. And, boy, was I glad I did because I was able to get across this idea that, yes, this is a narrower ground on which you can affirm it. And I think everybody agrees. I think even the dissenting justices ultimately in the case agreed that, if Congress had expressly called it a tax, it would be indisputably constitutional. So, really the fight was just about whether there was a magic word there or not. And I thought, if I could frame the thing up in those terms, that we’d have a pretty good shot because it would be a little weird to say, yes, Congress can do it if it uses the magic words. But because Congress didn’t use the magic words, they can’t do it. That’s a different kind of question from the commerce power question of whether this is just going too far, which is a much harder question to answer, I think.

Lithwick: Did you feel at that moment, Hey, I have the chief? Or was that not that way?

Verrilli: No.

Lithwick: No way.

Verrilli: No. No. No. I thought it was like a jump ball kind of thing. You know, could go either way. But I didn’t think I had that one in the bag, not by any means. No.

Lithwick: And I think I just want to ask—and you can tell me that you can’t answer—I know this week was a big win on affirmative action in Fisher. It was certainly not a win in United States v. Texas. It was a tie. Can you talk at all about both what that means going forward? But also president Obama framed this as a real referendum on what it means to have eight justices. Does that get through? Is this a way of concretizing for people that having eight justices is a problem?

Verrilli: Well, it may be. You know, it may be. We’ll see how the public reacts to it. But the fact that you have a policy of such consequence directly affecting millions of people and you have a legal question of great consequence about the scope of the president’s authority to act in implementing the immigration laws in this way and you have a one-line decision from the court affirming by an equally-divided court, it’s an inevitable consequence of where we are.

And I’m certainly not criticizing the court for issuing that ruling. It is what it is. It’s their practice to, when it’s a tie, to just issue a one-line ruling. And there are reasons for that. But when there’s something this important at stake, it’s not a great thing for the country that it gets resolved, at least resolved provisionally in the way that it did.

Lithwick: I want to ask you a last question about tone, because this is something that everybody has said about you, and I think they say it almost disparagingly, is that you’re such a gentleman. “You’re a lawyer’s lawyer.” Why don’t you shout more? And certainly I think at the outset there was really a lot of criticism of how sort of mild-mannered Clark Kent you were. And I think particularly on the left, progressives wanted more bombast and more. I almost want to say Scalia-like, you know, shaking of fists. I’ve read you quoted, saying you felt your job was always to take the temperature down in that chamber. But can you talk a little bit? I know you tweaked your tone a little bit.

Can you talk a little bit about partly just being in this moment where sharp, sharp defense at the court, some eye-rolling at the court? This is a very high-intensity bunch of justices. Your decision was always to modulate that by being unbelievably calm. Is that fair?

Verrilli: Yeah, and I’ve actually thought a lot about this. And there are three kind of conscious reasons for it. One is that I’m not a private litigant. I’m representing the United States. And I’m representing the United States, and my office is representing the United States day after day in front of the court. And I think it’s the right thing to do, to carry that out with some dignity and some respect for the process and respect for the institution. And so that led me to just, you know, move the dial a little bit in the direction of calmness.

The second thing I thought was that, as a pragmatic matter, it was the sensible way to do this because, you know, without trying to pigeon-hole anybody, I think it is fair to say that in the main, I’m arguing for progressive positions on behalf of a progressive administration in front of a court who, before Justice Scalia’s death, had a conservative majority that was quite conservative, frankly.

And that my job was always to pull a vote over from somebody who was likely to be at least at the outset disinclined to agree with me on some things or at least disinclined to agree with the policy that I was defending. Maybe they would agree with the legal principles but not the policy. And that it wasn’t going to do me a lot of good to give a stirring speech to try to move that fifth vote over. And a good example of that is Shelby County, you know, where I do think there was a lot of concern from the left that I didn’t go up there and, you know, give a ringing speech about the Edmund Pettus Bridge. And, you know, I would—you know, part of me, of course, wanted to do that, you know, talk about the Edmund Pettus Bridge and the iconic nature of the statute and its place in our history. But I thought there was zero chance that that was going to help me get the fifth vote I needed in the case. And, if anything, it would be counterproductive because I’d be kind of sending a message that implied something about the people who were inclined to vote against me. And it just seemed as a pragmatic matter not the right way to do it.

And then the third reason was that, and the first two I sort of had from the outset in my mind that those were reasons to stick. On the third one, I came to appreciate over time, which is that, if my baseline is calm, then the moments when I reach for something are going to have more of an impact because they’re going to stand out and that I’ll depart upward from my calm baseline. And just the fact that I’m doing it signals that I am saying something that I think is really important. And the moments when I think about that are that very end of the third day in health care, and the Obergefell—especially the closing part of Obergefell. And there are several other times like that where I felt like, OK, I’m going into this other mode. And, you know, one thing I’m very grateful about is that the justices actually respected that. Almost always when I went into that mode, they stopped interrupting and listened. And so I know—who knows whether those moments made any difference in the outcomes of the decisions? But I felt like, you know, if I’d been up at that level all the time, then it was just going to be, you know, one more sentence coming out of my mouth. But if it was different in that it was going to, hopefully, have more of an impact, as I said, that wasn’t entirely conscious at the beginning.

But I did, after a couple of years, I realized that this was actually true, that his gave me the ability to go to a different place and, hopefully, have a stronger impact.

Lithwick: It’s funny, I’ve been thinking so much in this last couple of months about how grateful I am to cover the court because the constraints of calm and civility are really palpable when you look across the street, and that, you know, I feel like the discourse has become so overheated that, you know, we talk about everything in the exact tone that seems to sort of preclude reason and to preclude the possibility of agreement.

And more and more, I’m sort of responding to what you’re saying by just thinking, this is such a moment when it feels that the whole country could learn from the way we speak to each other in the court, you know, and understanding that we are repeat players, that we have reputations, that lying is not generally a good idea. And that, you know, the way we treat each other in that building stands for the proposition that there can be reason and there can be compromise. And it just feels as though it’s kind of dissipated in so much of political discourse.

Verrilli: Yeah. I completely agree with that. And one thing I’ve experienced and I feel really grateful for now that I’m on my way out is that I felt that the justices gave that back to me. I really did. You know, of course, you can have some sharp exchanges. That’s the nature of the thing, and that’s fine. But really in the main I felt like the tone from them was, “Yeah. We may not agree with you, but we’re going to have a discussion about this.” And it did. You know, there wasn’t, I might’ve in a case where I prevailed, you know, the next time I’m up there, there was no sort of ill will hanging over from the prior case. You know, we had the same discussion again.

Lithwick: When you announced that you were stepping down, President Obama said this:

Thanks to his efforts, 20 million more Americans now know the security of quality affordable health care; we’re combating more discrimination so that more women and minorities can own their piece of the American dream; we’ve reaffirmed our commitment to ensuring that immigrants are treated fairly; and our children will now grow up in a country where everyone has the freedom to marry the person they love.

You have really presided over an amazing, amazing time as solicitor general. And I think I just want to say thank you for your service. And I hope that you go off and do whatever the next fantastic thing is. We thank you.

Verrilli: Well, I feel so blessed to have had the chance to do this job in this moment in our history. It’s been an incredible thing. So, thank you.