And so the Trump administration’s long-awaited national security shuffle begins. Rex Tillerson is soon to be ousted as secretary of state—no surprise, given that he was once quoted as calling Trump “a fucking moron” (then didn’t deny doing so when given the chance) and that Trump had publicly undermined one of the secretary’s only diplomatic ventures.

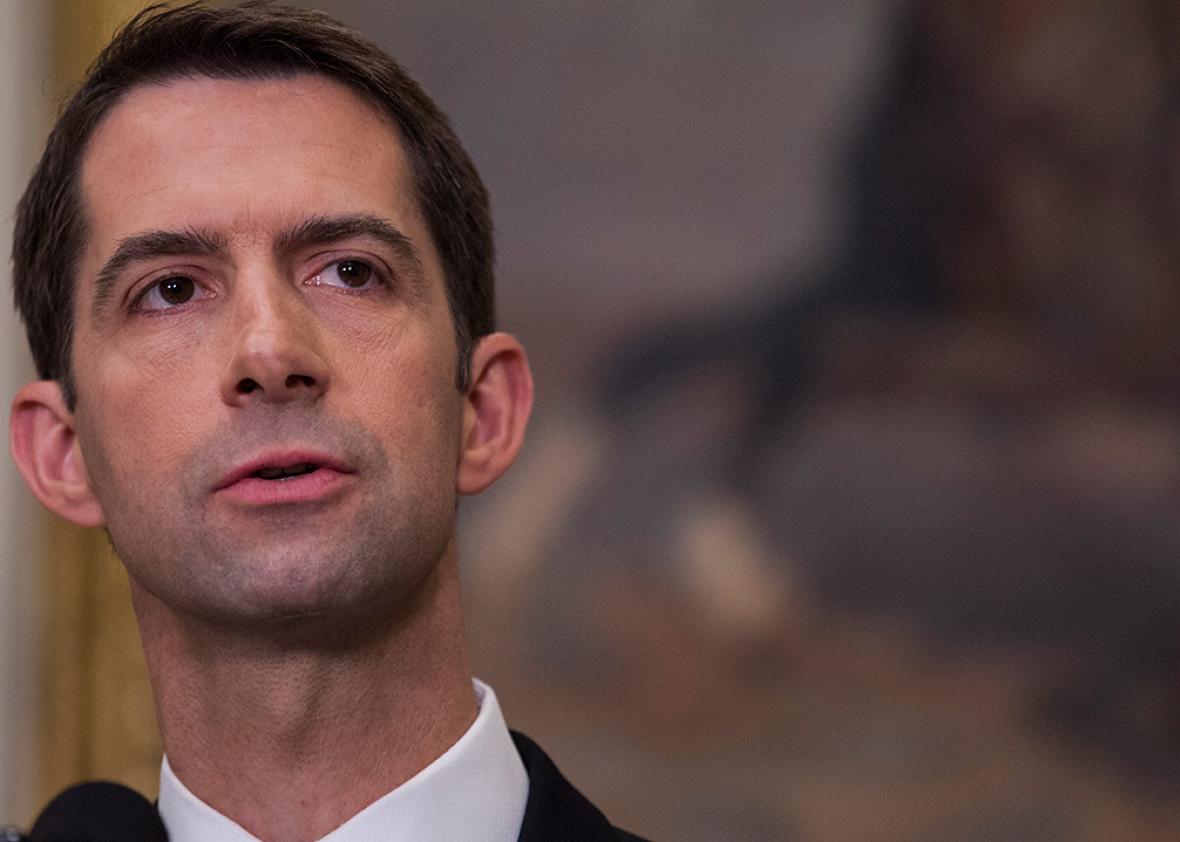

The New York Times reports today that Tillerson’s likely replacement at State will be Mike Pompeo, currently director of the CIA, and Pompeo may be succeeded—this is reported as the “consensus choice,” but is not yet a firm pick—by first-term Republican Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas.

Pompeo has been Trump’s political lapdog at Langley, but Tillerson, former CEO of ExxonMobil, has been such a dreadful disappointment at the State Department—a mix of clueless and ineffectual—that even Pompeo might prove to be an improvement.

However, if Cotton gets the nod to replace Pompeo at the CIA, the results are almost certain to be disastrous.

First, Cotton is an ideologue to an extent beyond any CIA director except possibly William Casey during the Reagan administration. Since his election to the House in 2012, and then to the Senate two years later, Cotton has taken outspoken stances far to the right on every issue domestic and foreign.

Most notably, during the debate over the Iran nuclear deal, Cotton not only opposed the accord (as most Republicans did) but wrote a letter to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, claiming that President Obama had no authority to sign such an agreement and that the next Congress would override it—an act of unusually brazen partisanship that some said violated the Logan Act, which bars private citizens from engaging in foreign policy. (Cotton, who graduated from Harvard Law School, evaded that issue by labeling the missive—which 46 other Republicans co-signed—an “open letter” rather than a direct communiqué to a foreign leader.)

He served on Trump’s national security transition team after the election, was on the shortlist for secretary of defense, and since Inauguration Day, has defended the president from charges far and wide. When reports first arose that Trump campaign officials had colluded with Russians to influence the election, Cotton dismissed them as a “ridiculous” plotline out of some spy novel. He also tried, with no success, to puncture holes in ousted FBI Director James Comey’s testimony in June.

His track record on issues of special pertinence to someone vying for the CIA job is even more alarming. He has supported waterboarding as a valid interrogation technique—a view that could wrench the agency back to its darkest practices. And when the New York Times reported nervousness among intelligence officials that Michael Flynn had received CIA briefings even after the Justice Department warned that he might be compromised by foreign agents, Cotton unleashed a tweetstorm, in the end suggesting that the Times reporters, whom he cited by name, should be investigated by the FBI for revealing classified information.

The upshot is that the CIA, which is supposed to be an independent source of intelligence as far removed as possible from political pressures, should not be led by a partisan firebrand. Yet strict loyalty is precisely what Trump wants from a CIA director—and from his entire inner circle.

Trump got off to a bad start with the intel community and has done little to repair the damage. During the presidential campaign, he dismissed the unanimous intelligence community’s estimate that Russian President Vladimir Putin hacked Hillary Clinton’s campaign in an effort to help Trump’s their findings on Russian interference in the election, comparing it to the intelligence failure on Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction. On his second day as president, he made highly politicized and self-serving remarks in front of the CIA’s memorial wall. He has recently dissed James Clapper and John Brennan—longtime intelligence professionals who held senior positions during the Obama administration—as “hacks.”

Pompeo—who, before getting the CIA job, was a Republican congressman from Kansas with Tea Party affiliations and financial backing from the Koch brothers—has done little to abate these concerns. He has, at least, publicly acknowledged that top Russian officials did try to influence the 2016 election—which sets him apart from Trump—but he also said the intelligence community had concluded that the attempt had no effect on the election’s outcome. In fact, the intel agencies noted that there was “no way for us to gauge” whether it had an effect, in part because such matters lie far outside their purview. This is a subtle but serious distortion.

Quite aside from these matters, on the basis of their records, both Pompeo and Cotton seem ill-suited for the job. They both sat on congressional intelligence committees and served in the military, Cotton as a platoon commander in Iraq and a logistics officer in Afghanistan. (Cotton is widely admired for enlisting in the Army not as an officer in the JAG Corps, which he could easily have done on the strength of his Harvard Law degree, but rather as a corporal in basic training for the infantry, rising to the rank of captain.)

But unlike the vast majority of CIA directors, neither has experience in intelligence or in managing a large organization. Former officials who have worked with both men call them “smart,” “enthusiastic,” and say they “study the issues.” But they also call them “green.” One said of Pompeo, “He is about certainty and answers,” whereas the job “is all about ambiguity and questions”—and added that this is “true of Cotton,” whom he likes “even more than Pompeo.”

This, too, is a trait that they share with Trump, who reportedly wants his intelligence briefings to cover no more than three issues, each in no more than a single page, with no minority views or caveats: just the consensus conclusion, no ambiguities. This is dangerous enough in a president and potentially fatal in an intelligence director, who needs to go into the Oval Office at least knowing, even if he doesn’t explicitly recite, the full range of possibilities.

If Cotton is nominated for the job, he will almost certainly be confirmed; the Senate rarely eats its own in this regard. (See, for instance, the confirmation of Jeff Sessions as attorney general despite misgivings even on the part of some Republicans.)

Trump seems to believe that the entire government should serve his interests and desires, in the same way that his family business did (and still does) when he was (and still is) a real-estate mogul. Pompeo’s move to the State Department and Cotton’s ascension to Langley would further consolidate that effort.