President Trump’s executive order giving Steve Bannon a seat on the National Security Council’s Principals Committee is an assault on common sense and tradition—that much is obvious. It also appears to be a violation of federal law.

According to Title 50 of the U.S. Code, Section 3021, which established the National Security Council, it “shall be composed of” the president; the vice president; the secretaries of state, defense, and energy; and “the secretaries and undersecretaries of other executive departments and of the military departments, when appointed by the President by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, to serve at his pleasure.”

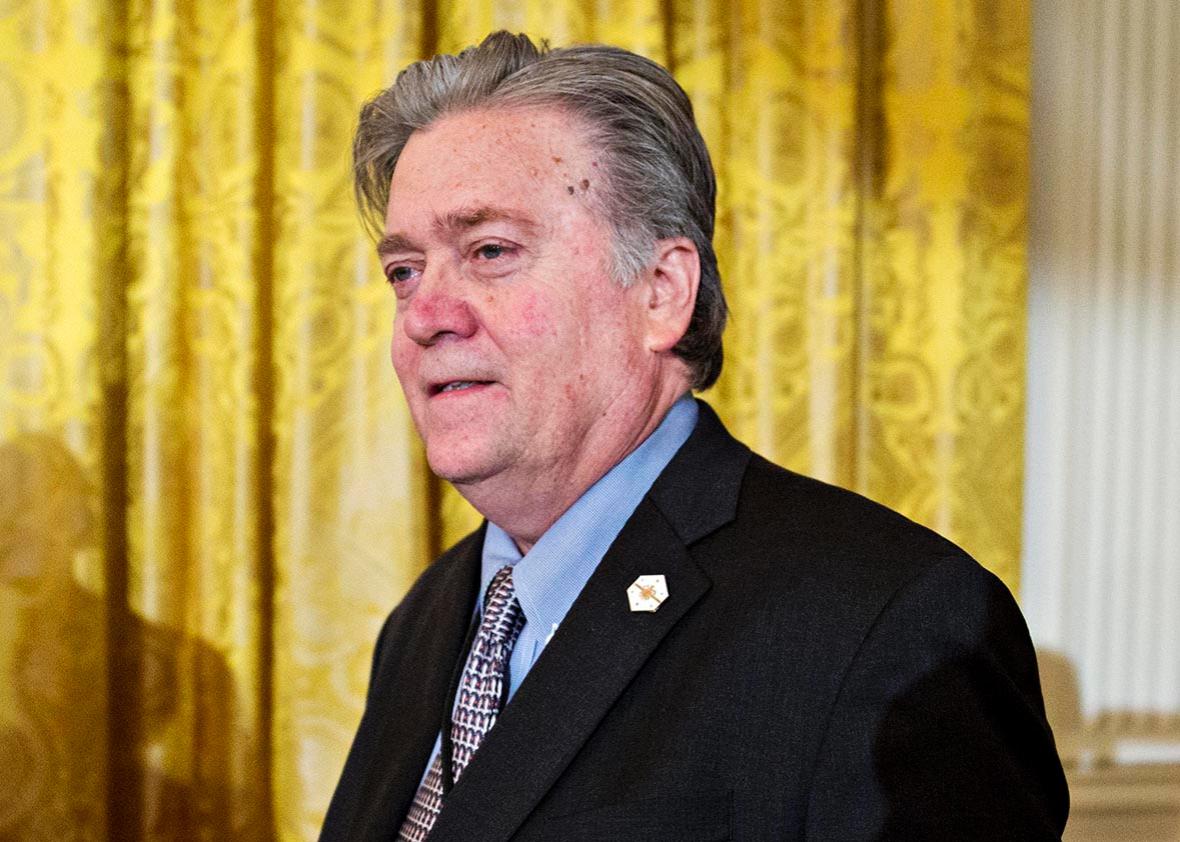

As the president’s chief political strategist, Bannon is not a secretary or undersecretary of any department. Nor, as a member of the White House staff, has he been confirmed by the Senate. So he is not eligible to serve on the NSC, and if that’s the case, he is doubly ineligible to sit on its Principals Committee—the assembly of Cabinet secretaries and department heads (sometimes including the president) that discusses and makes decisions on high-level U.S. foreign and military policy.

Trump’s executive order of Jan. 28, titled “Presidential Memorandum: Organization of the National Security Council and the Homeland Security Council,” affirms that the Principals Committee “shall continue to serve as the Cabinet-level senior interagency forum for considering policy issues that affect the national security interests of the United States.” The memo then goes on to state that the committee’s “regular attendees” shall include the secretaries of state, treasury, defense, and homeland security; the attorney general; and the national security adviser, who formally calls such meetings. (The director of national intelligence and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff are also invited to attend “when issues pertaining to their responsibilities and expertise are to be discussed.”) All this is consistent with the committee’s composition under Presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush.

But, among those other senior officials, the memo also includes in its list of regular attendees “the Assistant to the President and Chief Strategist”—in other words, Steve Bannon.

No such position—not even a broad category that includes this position—is listed in the statute governing the NSC. A presidential memorandum doesn’t override federal law. Therefore, Bannon should not be given a seat at the table unless Congress amends the law. I asked Eugene Fidell, a prominent national-security lawyer at Yale University, whether he agreed with this interpretation. He did, saying, “Congress created the NSC and prescribed its composition, and that composition is it.”

The aides who wrote Trump’s memorandum devised some “cute language,” as Fidell calls it, that they might have intended to skirt this basic fact. At one point in the section on the Principals Committee, the memo notes that the national security adviser or homeland security adviser shall set the agenda “in consultation with the appropriate committee members.” In the next paragraph, the memo lists the committee’s “regular attendees.” (Italics added.) A clever White House lawyer might argue that Bannon is listed as a mere attendee, not a member, noting that Obama’s chief strategist, David Axelrod, sometimes attended Principals Committee meetings.

But this argument is specious in two ways. First, Axelrod was not (in the words of the memo) a “regular attendee”: He attended the meetings occasionally, sitting along the wall with other aides and deputies, not at the table, and he never said a word. (Axelrod’s predecessors, including Karl Rove, the powerful chief strategist for George W. Bush, never so much as sat in.)

Second, and more to the point, the memo makes no distinction between “attendee” and “member.” Neither term is defined. And since the list of “regular attendees” includes Cabinet secretaries and the chief strategist—all as part of the same list, with no separation into subsections A and B—then it can be inferred that the two terms are synonymous. In any case, if a White House lawyer did offer such an argument, Fidell says it would “circumvent congressional intent.”

The substantive problems with this memo are clear-cut. The NSC, especially its Principals Committee, is the one place where the Cabinet secretaries and top military and intelligence officials meet to discuss national-security crises, events, and policies, hashing out their disparate views and perspectives to come up with a plan of action—or to present a set of options for the president to approve or reject. When presidents make a final decision, they are entitled, perhaps even obligated, to take into account their own purely political judgments. But political considerations, such as those that rivet the likes of Bannon or Axelrod, should not play a prominent role in the highest-level interagency discussions of these issues.

Several senators, including some Republicans, have made this same point in their objections to Bannon’s elevation as an NSC principal. What they may not realize is that they can do something to stop it. They can simply assert that the law takes precedence over a presidential memorandum, and the law makes no provision for his participation. And if Trump then drafts a bill giving Bannon full membership, they can vote it down.